Two Essays on Various Selves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

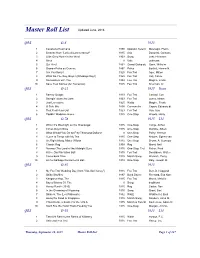

Master Roll List

Master Roll List QRS O-6 1925 1 Cavalleria Rusticana 1890 Operatic Selecti Mascagni, Pietro 2 Sextette from "Lucia di Lammermoor" 1835 Aria Donizetti, Gaetano 3 Little Grey Home in the West 1903 Song Lohr, Hermann 4 Alma 0 Vals unknown 5 Qui Vive! 1862 Grand Galop de Ganz, Wilhelm 6 Grande Polka de Concert 1867 Polka Bartlett, Homer N. 7 Are You Sorry? 1925 Fox Trot Ager, Milton 8 What Do You Say, Boys? (Whadaya Say?) 1925 Fox Trot Voll, Cal de 9 Somewhere with You 1924 Fox Trot Magine, Frank 10 Save Your Sorrow (for Tomorrow) 1925 Fox Trot Sherman, Al QRS O-21 1925 Roen 1 Barney Google 1923 Fox Trot Conrad, Con 2 Swingin' down the Lane 1923 Fox Trot Jones, Isham 3 Just Lonesome 1925 Waltz Magine, Frank 4 O Solo Mio 1898 Canzonetta Capua, Eduardo di 5 That Red Head Gal 1923 Fox Trot Van, Gus 6 Paddlin' Madeline Home 1925 One-Step Woods, Harry QRS O-78 1915 Lbl 1 When It's Moonlight on the Mississippi 1915 One-Step Lange, Arthur 2 Circus Day in Dixie 1915 One-Step Gumble, Albert 3 What Would You Do for Fifty Thousand Dollars? 0 One-Step Paley, Herman 4 I Love to Tango with My Tea 1915 One-Step Alstyne, Egbert van 5 Go Right Along, Mister Wilson 1915 One-Step Brown, A. Seymour 6 Classic Rag 1909 Rag Moret, Neil 7 Norway (The Land of the Midnight Sun) 1915 One-Step, Trot Fisher, Fred 8 At the Old Plantation Ball 1915 Fox Trot Donaldson, Walter 9 Come back Dixie 1915 March Song Wenrich, Percy 10 At the Garbage Gentlemen's Ball 1914 One-Step Daly, Joseph M. -

Welcome, We Have Been Archiving This Data for Research and Preservation of These Early Discs. ALL MP3 Files Can Be Sent to You B

Welcome, To our MP3 archive section. These listings are recordings taken from early 78 & 45 rpm records. We have been archiving this data for research and preservation of these early discs. ALL MP3 files can be sent to you by email - $2.00 per song Scroll until you locate what you would like to have sent to you, via email. If you don't use Paypal you can send payment to us at: RECORDSMITH, 2803 IRISDALE AVE RICHMOND, VA 23228 Order by ARTIST & TITLE [email protected] S.O.S. Band - Finest, The 1983 S.O.S. Band - Just Be Good To Me 1984 S.O.S. Band - Just The Way You Like It 1980 S.O.S. Band - Take Your Time (Do It Right) 1983 S.O.S. Band - Tell Me If You Still Care 1999 S.O.S. Band with UWF All-Stars - Girls Night Out S.O.U.L. - On Top Of The World 1992 S.O.U.L. S.Y.S.T.E.M. with M. Visage - It's Gonna Be A Love. 1995 Saadiq, Raphael - Ask Of You 1999 Saadiq, Raphael with Q-Tip - Get Involved 1981 Sad Cafe - La-Di-Da 1979 Sad Cafe - Run Home Girl 1996 Sadat X - Hang 'Em High 1937 Saddle Tramps - Hot As I Am 1937 (Voc 3708) Saddler, Janice & Jammers - My Baby's Coming Home To Stay 1993 Sade - Kiss Of Life 1986 Sade - Never As Good As The First Time 1992 Sade - No Ordinary Love 1988 Sade - Paradise 1985 Sade - Smooth Operator 1985 Sade - Sweetest Taboo, The 1985 Sade - Your Love Is King Sadina - It Comes And Goes 1966 Sadler, Barry - A Team 1966 Sadler, Barry - Ballad Of The Green Berets 1960 Safaris - Girl With The Story In Her Eyes 1960 Safaris - Image Of A Girl 1963 Safaris - Kick Out 1988 Sa-Fire - Boy, I've Been Told 1989 Sa-Fire - Gonna Make it 1989 Sa-Fire - I Will Survive 1991 Sa-Fire - Made Up My Mind 1989 Sa-Fire - Thinking Of You 1983 Saga - Flyer, The 1982 Saga - On The Loose 1983 Saga - Wind Him Up 1994 Sagat - (Funk Dat) 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - I'd Rather Leave While I'm In Love 1977 1981 Sager, Carol Bayer - Stronger Than Before 1977 Sager, Carol Bayer - You're Moving Out Today 1969 Sagittarius - In My Room 1967 Sagittarius - My World Fell Down 1969 Sagittarius (feat. -

The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 4-4-1934 Sandspur, Vol. 38 No. 26, April 4, 1934 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol. 38 No. 26, April 4, 1934" (1934). The Rollins Sandspur. 394. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/394 ROLLINS COLLEGE LIBRARY WINTER i-'ARi\, i'LORlDA Attend Chapel ttoiUnsi^Santi0pur VOLUME 38 WINTER PARK, FLORIDA, MAY 9, 1934 Helen Welch and Jeannette WORLD POETS ATIEND RHEA SMITH HAS Houghton Offer Song Recitals SCHRAGE WINS FLASHES Jeannette Houghton, contralto, Helen Welch, soprano, assisted YEAR'S LEAVE assisted by Vincent Canzoneri, vio by Virignia Orebaugh, pianist, PRESIDENCY OF From the United Press linist, gave a senior recital Tues gave a senior recital Thursday eve Popular History Prof to Study day e/aning, May 8th, at tlv! ning. May 3, at the Woman's Club. For Ph. D. Woman'sClub. Mrs. Emelie Dough Mrs. Emelie Dougherty accompan FRANCE MAY DEFAULT erty and Lillias Parker accompany ied Miss Welch on the piano. The STUDENT BODY DEBT INDEFINITELY led Miss Houghton and Mr. Can program was as follows: Rhea M. Smith, -

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This Sheet Music Is Only Available for Use by ASU Students, Faculty, and Staff

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This sheet music is only available for use by ASU students, faculty, and staff. Ask at the Circulation Desk for assistance. (Use the Adobe "Find" feature to locate score(s) and/or composer(s).) Call # Composition Composer Publisher Date Words/Lyrics/Poem/Movie Voice & Instrument Range OCLC 000001a Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Original in E Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics 000001b Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Transposed in F Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics by Otto A. Harbach 000002a American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000002b American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000003a As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000003b As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000004a Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004b Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004c Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000005 Acrostic Song Tredici, David Del Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. -

Vince Giordano Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Born in Brooklyn, New York, Vince Giordano’s passion for music from the 1920s and 1930s, and the people that made it, began at age 5. He has amassed an amazing collection of over 60,000 band arrangements, 1920s and 1930s films, 78 recordings and jazz-age memorabilia. Giordano sought out and studied with important survivors from the period: Paul Whiteman’s hot arranger Bill Challis and drummer Chauncey Morehouse, as well as bassist Joe Tarto. Giordano’s passion, commitment to authenticity, and knowledge led him to create a sensational band of like-minded players, the Nighthawks. Giordano has single-handedly kept alive an amazing genre of American music that continues to spread the joy and pathos of an era that shaped our nation. A Grammy-winner and multi-instrumentalist, Giordano has played in New York nightclubs, appeared in films such as The Cotton Club, The Aviator, Finding Forrester, Revolutionary Road, and HBO’s Boardwalk Empire; and performed concerts at the Town Hall, Jazz At Lincoln Center and the Newport Jazz Festival. Recording projects include soundtracks for the award- winning Boardwalk Empire with vocalists like Elvis Costello, Patti Smith, St. Vincent, Regina Spektor, Neko Case, Leon Redbone, Liza Minnelli, Catherine Russell, Rufus Wainwright and David Johansen. He and his band have also recorded for Todd Haynes' Carol, Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World, Tamara Jenkins’ The Savages, Robert DeNiro’s The Good Shepherd, Sam Mendes’ Away We Go, Michael Mann’s Public Enemies, and John Krokidas’ debut feature, Kill Your Darlings; along with HBO’s Grey Gardens and the miniseries Mildred Pierce. -

Unfinished Book of Poetry 2021

The Unfinished Book of Poetry 2021 poetry from four Cork City secondary schools Published by Cork City Council, Cork City Libraries and Ó Bhéal Published in 2021 by Cork City Council, Cork City Libraries and Ó Bhéal Supported by the Arts Office, Cork City Council in partnership with Ó Bhéal The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for permissions should be addressed to the publisher. All rights reserved. Text © 2021 for each author as indicated www.obheal.ie Design and editing by Paul Casey Cover photograph by Daniel Smith Typesetting by Paul Casey and Daniel Smith Printed in Cork by City Print The Unfinished Book of Poetry 2021 Contents Foreword by Patricia Looney, Cork City Librarian 1 Assisting Writers’ Biographies 2 Coláiste an Phiarsaigh Réamhrá le / Introduction by Colm Ó Ceallacháin 4 Seán Ó Conaill 8 TY Sciobtha Uainn // Grá don Trá Sadhbh Ní Shúilleabháin Sa Bhaile Arís // Sneachta sa chlós // Mo Dheartháirín Óg // 10 Haikú // Looking Tess Sexton 13 A Trade // Sand // No Fishing // she cried on a train. Kiela Ní Dhochartaigh 15 Bogha Báistí Ruth Nic Pháidín 16 Green 99 // February // Haiku #1 // Haiku #2 Oisín Ó Luanaigh 19 Brionglóidí Tess Nic Cárthaigh 20 Cappuchino // Oighear Iodálach // Pis talún agus sceaimpí // Soilse fluaraiseacha // Truailliú // Expectations Caoilinn Ní Bhuachalla 23 Mo Ghrása // Neirbhís St. -

The Other Side of Me

THE OTHER SIDE OF ME THE OTHER SIDE OF ME Copyright © 2005 by Sidney Sheldon Family Limited Partnership All rights reserved. Warner Books Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com. ISBN: 0-7595-6729-8 First eBook Edition: August 2006 For my beloved granddaughters, Lizy and Rebecca so that they will know what a magical journey I had THE OTHER SIDE OF ME “He that has no fools, knaves nor beggars in his family was begot by a flash of lightning.” —Thomas Fuller 17th century English clergyman CHAPTER 1 t the age of seventeen, working as a delivery boy at Afremow’s drugstore in Chicago was the perfect job, Abecause it made it possible for me to steal enough sleeping pills to commit suicide. I was not certain exactly how many pills I would need, so I arbitrarily decided on twenty, and I was careful to pocket only a few at a time so as not to arouse the suspicion of our pharmacist. I had read that whiskey and sleeping pills were a deadly com- bination, and I intended to mix them, to make sure I would die. It was Saturday—the Saturday I had been waiting for. My parents would be away for the weekend and my brother, Richard, was staying at a friend’s. Our apartment would be deserted, so there would be no one there to in- terfere with my plan. At six o’clock, the pharmacist called out, “Closing time.” He had no idea how right he was. -

Patty Mulkey Collection Finding

Guide to the Patty Mulkey Collection Circa 1857-1996, [1940-1996] 27.0 linear feet 2007.001 Abstract Materials collected by Patty Mulkey relating to her interests and hobbies, especially her interest in history and her work with the River Heritage Museum, during her time in Cape Girardeau, Missouri; materials include sheet music, news clippings, photographs, scrapbooks, ledgers, and correspondence relating to Southeast Missouri. Processed by: Joshua Doll and Stephanie Baedke, March 2010 Special Collections and Archives Kent Library One University Plaza, MS 4600 Southeast Missouri State University Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 Phone: (573) 651-2245; Fax: (573) 651-2666; Email: [email protected] Descriptive Overview Provenance: Donated by Patty Mulkey in 1997. Citation: Patty Mulkey Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Southeast Missouri State University. Restrictions: Some of the original newspapers from Series XI are in fragile condition; however, they are microfilmed copies available for viewing in Special Collections and Archives. Separated Materials: The following materials can be located using the library’s online catalog. The Little River Drainage District of Southeast Missouri: 1907-present. Cape Girardeau, MO: Little River Drainage District of Southeast Missouri, 1989? Stacy, Jane Cooper. Louis Lorimier. Cape Girardeau, MO: Caxton, 1978. The following publication and parts of publications were removed: Kochtitzky, Otto. Otto Kochtitzky; the story of a busy life. Cape Girardeau, MO: Ramfre Press, 1957. pages: 38-139, & 145-147 Shoemaker, Floyd C. "Kennett: Center of a Land Reborn in Missouri’s Valley of the Nile." Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 52, No. 2, 1958 Jan: 106-107. History of Southeast Missouri. Embracing an Historical Account of the Counties of Ste. -

RECORDSMITH 1888-1930'S MP3/CD LISTINGS

RECORDSMITH 1888-1930's MP3/CD LISTINGS Email inquiries regarding selections to [email protected] (Hungarian) Baritone Tele van a város akáczfa virággal 1905 Col Cylinder 1905 (Hungarian) Geza Vago Egy városligeti kikiáltó 1906 Col Cylinder 1906 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders All By Yourself In the Moonlight 1929 1929 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Crazy words crazy tune Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Day You Came Along 1933 1933 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Do You Believe In Dreams (1926) 1926 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Don't Look At Me That Way (1928) 1928 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Give Me a Ukulele and a Ukulele Baby 1926 1926 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders He Ain't Done Right By Nell 1926 1926 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders I never see maggie alone Aaronson, Irving & Commanders If I had you (1929) 1929 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders I'll get by as long as I have you (1928) 1928 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders I'm Just Wild About Animal Crackers Aaronson, Irving & Commanders I've Got It Bad (1936) 1936 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Let's fall in love (1929) 1929 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Let's Misbehave 1928 1928 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Love In Bloom 1934 1934 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders My Scandinavian Gal Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Pump Song (1926) Victor 1926 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Waffles 1926 1926 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders Wimmin! Aaaah! Aaronson, Irving & Commanders & Irene Bordoni Don't Look At Me That Way 1928 (Victor LPV 1928 Aaronson, Irving & Commanders & Phil Saxe My Scandinavian Gal (By Yumpin' -

Women's Christmas Retreat 2018 the Path We Make by Dreaming

THE PATH WE MAKE by DREAMING A Retreat for Women’s Christmas JAN RICHARDSON If you would like to make a contribution in support of the Women’s Christmas Retreat, visit sanctuaryofwomen.com/womenschristmas.html We suggest a donation of $7, but any amount you would like to give will be greatly appreciated. Contributions will be shared with the A21 Campaign (a21.org), which works to end human trafficking and provide sanctuary, healing, and hope for those rescued from slavery. e e e All Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2018 by Jan Richardson janrichardson.com Prelude The Map Our Dreaming Made A Blessing for Women’s Christmas I cannot tell you But I tell you how far I have come that even here, to give this blessing the hope to you. that each star belongs No map to a light for the distance crossed, more ancient still, no measure for the terrain behind, and each dream no calendar part of the way for marking that lies beneath the passage of time this way, while I traveled a road I knew not. and each day drawing us closer For now, let us say to the day I had to come by when every path a different star will converge than the one I first followed, and we will see the map had to navigate by our dreaming made, another dream luminous in every line than the one that finally led us I loved the most.