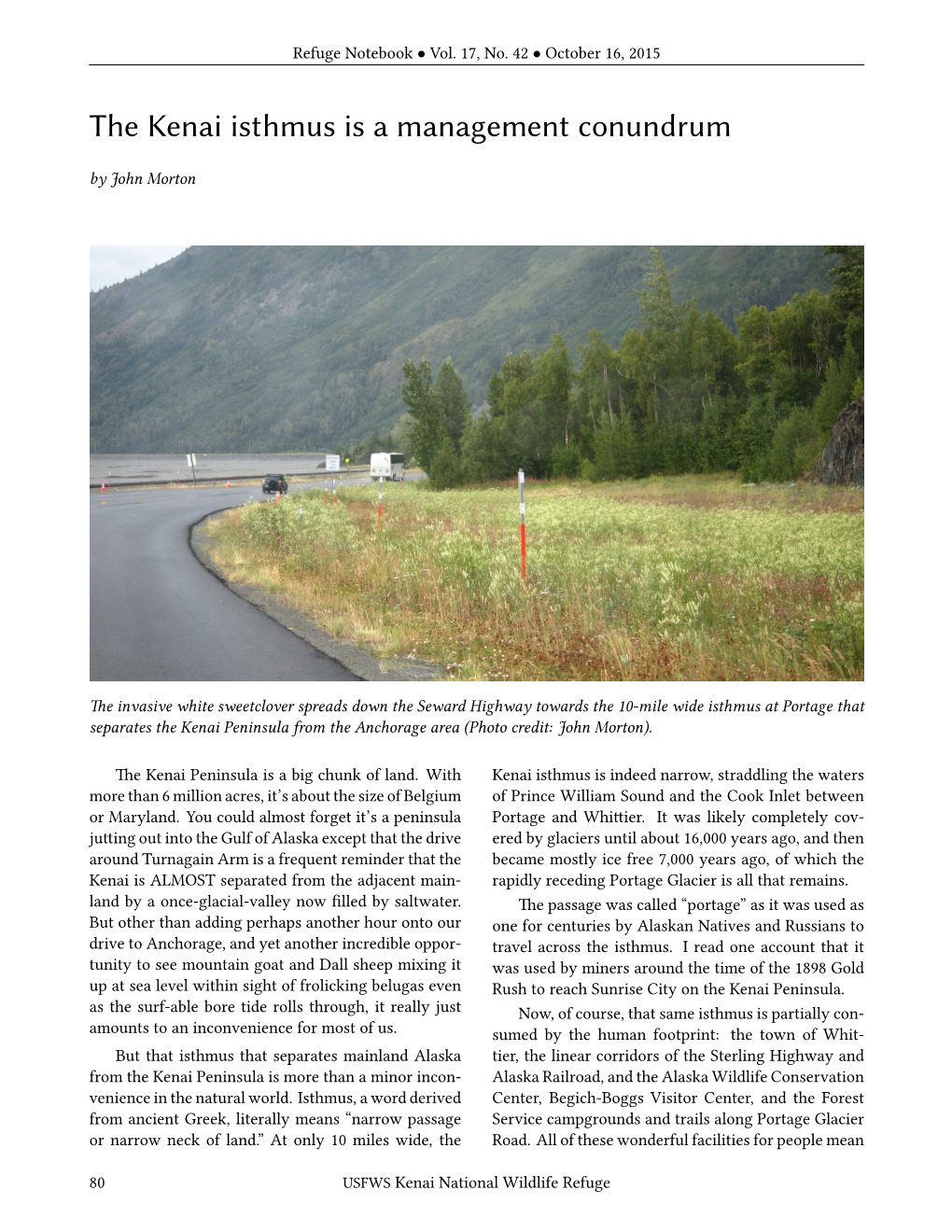

The Kenai Isthmus Is a Management Conundrum by John Morton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deposition and Preservation of Estuarine Sediment, Turnagain Arm, Cook Inlet, Alaska

DEPOSITION AND PRESERVATION OF ESTUARINE SEDIMENT, TURNAGAIN ARM, COOK INLET, ALASKA by DARRON G DEBOER B.S., Kansas State University, 2007 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Geology College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2009 Approved by: Major Professor Allen W. Archer Copyright DARRON GRANT DEBOER 2009 Abstract Turnagain Arm is the hypertidal (commonly exceeding 9 m) west-east trending extension of Cook Inlet in south-central Alaska. The inlet formed from a drowned glacial valley that was subsequently filled with tidal deposits of silt and fine sand. The tidal system is semidiurnal with a prominent diurnal inequality. There are also variations due to spring and neap tides. Turnagain Arm is home to a tidal bore generated during spring tides that can reach heights of up to 2 m and travel at speeds of up to 5 m/s. Current reversals can be dramatic with ebb tidal velocities of 6 m/s changing to flood velocities of 10 m/s over a period of a few minutes. During the initial flood tide, highly turbid water can rise as fast as 10 cm/min. This combination of elements results in a highly dynamic depositional setting. Measurements taken in the inner estuary during several neap-spring cycles in the summers of 2007-08 documented deposition upon mud bars of as much as 8.9 cm per tidal event. Conversely, erosion of up to 13.5 cm per tidal event has been measured. The highest rates of deposition and erosion occurred during the spring tides while much lower rates occur during the neap tides. -

Admiralty Island National Monument

ADMIRALTY ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENT DESCRIPTION At a glance: Admiralty Island National Monument (NM) is located on Admiralty Island NM quick facts Admiralty Island, 15 miles southwest of Juneau in south- east Alaska, and is accessible only by water or air. The Date established: Dec. 1, 1978; Dec. 2, 1980 island is characterized by rugged coastline, remote old growth rainforest, towering mountains, and alpine tundra Established by: Presidential proclamation, President with permanent icefields. It hosts the largest concentration Jimmy Carter (1978); Congressional designation, Public of brown bears and nesting bald eagles in the world, as Law 96-487 (1980) well as harbor seals, porpoises and sea lions, humpback Forest Service region: 10, Alaska Region whales, and all five species of Pacific salmon in its waters. More than 90 percent of the monument is designated as State: Alaska the Kootznoowoo Wilderness, nearly 1 million acres. Ad- Associated national forest: Tongass miralty Island has been the home to the Tlingít people for approximately 10,000 years. The monument area continues Total Forest Service acres: 997,226 to provide subsistence for these Alaskan Natives. Angoon, Reasons designated: “archaeological, cultural, and Admiralty Island’s only permanent community, continues historical resources, ecological and scientific value” to be an important cultural base. (Presidential Proclamation, 1978) BACKGROUND The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) of 1971 honored the rights of Alaska Natives to select approxi- People and visitors mately 44 million acres of Federal land in Alaska and au- thorized the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw 80 mil- Nearest metropolitan area: no metro areas within lion acres of land to be studied for possible additions to 500 miles the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Forest systems. -

Table 4.3 TURNAGAIN

Anchorage WetlandsManagement Plan -2012Public HearingDraft Page97 Table 4.3 TURNAGAIN ARM WETLAND DESIGNATIONS, ENFORCEABLE AND ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES Note: General Permits: The Corps of Engineers issued five separate General Permits (GPs) to the Municipality that covers development projects in “C” wetlands in Anchorage. The GPs are reviewed and renewed every five years. The most recent Anchorage GPs were issued in April, 2010. Under current GP procedures, the Municipality determines whether a proposed fill project in “C” wetlands is consistent with the GP terms and conditions. The Anchorage GPs are applied to only “C” wetlands as designated in the AWMP. The GPs do not apply to “A” or “B” wetlands and some “C” sites are excluded. Attachment A-Table 1 of the Anchorage GPs identifies which “C” wetland parcels are eligible for and which are excluded from the GPs. Attachment B-Table 3 of the GPs assigns site specific restrictions and design criteria to each eligible “C” wetland. The AWMP Table 4.1 management strategies notes which “C” wetlands are eligible for the GPs and references applicable site-specific restrictions and design criteria assigned to each site in the GPs. Refer to the current GPs for details and explanations of these requirements. Link: http://www.muni.org/departments/ocpd/planning/physical/envplanning/Pages/default.aspx. During the issuance of the current General Permits, the Corps included several previously unmapped wetlands as eligible for the GP. These are referenced as “U” wetlands in the General Permit documents. This AWMP revision includes these “U” sites and designates them as “C.” *(New sites now classified as “D” or “P” and former “U” sites now designated “C” are listed in blue.) Site #, listed in column 1 of the table, references individual wetland sites or collective groups of wetlands that are in the same geographic area and perform similar functions. -

Physiography, Texture, and Bedforms in Knik Arm, Upper Cook Inlet, Alaska

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PHYSIOGRAPHY, TEXTURE, AND BEDFORMS IN KNIK ARM, UPPER COOK INLET, ALASKA DURING JUNE AND JULY, 1980 by Susan Bartsch-Winkler Open File Report 82 - 464 1982 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature INTRODUCTION Knik Arm is located in upper Cook Inlet, and extends from the mouths of the Knik and Matanuska rivers on its northeastern end to the narrows formed by Point MacKenzie and Point Woronzof on its southwest ern end (figure 1). The Knik Arm estuary is approximately 50 km long and 6 km wide. It is surrounded by low-lying glacial debris of Pleist ocene and Holocene ages (Karlstrom, 1964). The city of Anchorage and its outlying suburban communities are located along the southern shore, and the rural expansion into the Matanuska Valley, including the small village of Knik, flank its northeastern and northern shoreline. The areas to the north and northwest are currently undergoing rapid commer cial and industrial expansion, and feasibility studies of several sites are underway for the Knik Arm bridge crossing to link the larger communities on the south shore with the rapidly developing areas to the north and northwest. This textural study represents baseline data for Knik Arm sedi ments prior to any major man-made alteration of the upper Inlet region. The setting is macrotidal, with tide ranges in excess of 35 feet (10 meters). A small tidal bore less than 1/3 meter in height accompanies each incoming tide, forming near the limit of the intertidal zone near Goose Bay and the Eagle River mudflats and then moves slowly northeast ward up the Arm (figure 2). -

Of 18 STATE of ALASKA DEPARTMENT

STATE OF ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Seward Highway MP 105-107 Windy Corner Proposed Commissioner’s Finding ADL 232839 (DOT&PF) ADL 232892 (ARRC) ADL 233527 (Closure of Section Line Easement) OSL 1632 (ARRC relinquished lands) 1. Proposed Action The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (DOT&PF) is proposing to improve the Seward Highway (highway) by relocating the rights-of-way and the railroad rights- of-way of the Alaska Railroad Corporation (ARRC) between highway mileposts (MP) 105 and 107 also known as “Windy Corner,” (project) within Chugach State Park (CSP). The purpose of this project is to implement safety upgrades and improve traffic operations. The highway segment within CSP proposed for improvement supports heavy commercial, recreational, and residential traffic and is located in one of five designated safety corridors in Alaska, due to the elevated rate of high-severity (e.g., fatal and major injury) crashes. As a popular area for viewing wildlife and recreating along the highway, traffic operations are frequently disrupted by motorists slowing and parking along the shoulder of the highway. This creates a high differential in speeds combined with limited sight distance and uncontrolled movements of traffic entering and exiting the highway that results in an elevated rate of severe crashes in the highway corridor. The objective of the project is to address long-standing traffic safety concerns. This will be done by realigning and dividing the highway to meet current design standards, in addition to adding auxiliary lanes for accelerating, decelerating and turning traffic, and constructing a recreational and parking area. -

The 1964 Prince William Sound Earthquake Subduction Zone Steven C

Adv. Geophys. ms. Last saved: 2/12/2003 6:lO:OO PM 1 Crustal Deformation in Southcentral Alaska: The 1964 Prince William Sound Earthquake Subduction Zone Steven C. Cohen Geodynamics Branch, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 2077 1 email: Steven.C.Cohen @ .nasa.gov; phone: 301-6 14-6466 Jeffrey T. Freymueller Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775 Outline: 1. Introduction 2. Tectonic, Geologic, and Seismologic Setting 3. Observed Crustal Motion 3.1 Coseismic Crustal Motion 3.2 Preseismic and Interseismic (pre-1964) Crustal Motion 3.3 Postseismic and Interseismic (post-1964) Crustal Motion 4. Models of Southcentral Alaska Preseismic and Postseismic Crustal Deformation 5. Conclusions 6. References Adv. Geophys. ms. Last saved: a1 a2003 6:lO:OO PM 2 1. Introduction The M, = 9.2 Prince William Sound (PWS) that struck southcentral Alaska on March 28, 1964, is one of the important earthquakes in history. The importance of this Great Alaska Earthquake lies more in its scientific than societal impact. While the human losses in the PWS earthquake were certainly tragic, the sociological impact of the earthquake was less than that of is earthquakes that have struck heavily populated locales. By contrast Earth science, particularly tectonophysics, seismology, and geodesy, has benefited enormously from studies of this massive earthquake. The early 1960s was a particularly important time for both seismology and tectonophysics. Seismic instrumentation and analysis techniques were undergoing considerable modernization. For example, the VELA UNIFORM program for nuclear test detection resulted in the deployment of the World Wide Standard Seismographic Network in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Lay and Wallace, 1995). -

Kenai Mountains- Turnagain Arm National Heritage Area

“Discover the story” Kaylene Johnson-Sullivan March 7th, 2017 What is a National Heritage Area? “National Heritage Areas are places whose stories tie our Nation together.” -- Dr. Herman Blake Places where outstanding natural, cultural, historic and scenic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally important landscape Established by Congress Funded through National Park Service Remain locally planned and driven Designation has no effect on property rights Kenai Mountains- Turnagain Arm National Heritage Area The KMTA NHA includes nine communities and sections of: • Chugach State Park • Chugach National Forest • Kenai Fjords National Park Administered by KMTA CCA, a local 501 (3) non-profit organization How do we work? Board members from eight NHA communities Twice -annual grant solicitation Grants must be matched 1:1 by non-federal funds Community-based grants and area wide projects Hope Hope Trail Safety Public lands connectivity Resurrection Pass Johnson Pass Economic development Infrastructure Trailhead parking Federal highway funds Seward Highway Partnerships & Support Community of Hope Hope Inc. Hope Historical Society Local contractor and trails advocates Hope School Kenai Peninsula Borough Alaska Department of Transportation Alaskan Senators Murkowski and Sullivan Key partner: Chugach National Forest Opportunities KMTA Can Help E stablish connections between trails on federal, state, and borough lands Coordinate efforts of state, federal and local partners Facilitate development of missing links that connect trails across jurisdictional boundaries Challenges Identifying agency(ies) to own and maintain trail Working with state, federal, and local agencies that each have their own unique processes and time-lines Pursuing Federal Funding in 2018 Discover the Story [email protected] 907-360 -0480 Kaylene Johnson-Sullivan, Executive Director . -

Upper Turnagain Landscape Assessment (UTLA) Is an Ecosystem Analysis at the Landscape Scale; It Is Both an Analysis and an Information Gathering Process

United States Department of Agriculture Upper Turnagain Forest Service Landscape Assessment Glacier Ranger District, Chugach National Forest July 2004 USDA Forest Service, Region 10, Alaska Photo: Portage Glacier and Portage Lake, 1984. Team: Betty Charnon – Co-Team Leader, Vegetation Chandra Heaton – Co-Team Leader, Database, GIS (through July 2003) Ricardo Velarde – Soils, Geology Bill MacFarlane – Hydrology Cliff Fox - Mining Sean Stash – Fisheries Aaron Poe – Wildlife Alison Rein – Recreation Teresa Paquet – Special Uses Linda Yarborough – Heritage Resources Pat Reed – Human Dimension Rob DeVelice – EMDS/Netweaver Approved by: /s/ James M. Fincher Date: 7/21/04 James M. Fincher, District Ranger The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Upper Turnagain Landscape Assessment (UTLA) is an ecosystem analysis at the landscape scale; it is both an analysis and an information gathering process. The purpose is to develop a geographically explicit understanding of the important resources, processes, patterns and interactions occurring on the assessment area. -

Chugach Access Plan

CHUGACH ACCESS PLAN Public Hearing Draft July 2012 Chugach Access Plan Public Hearing Draft July 2012 Municipality of Anchorage With Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation 1 Table of Contents 2 3 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 4 Background and Overview ................................................................................................. 1 5 Purpose and Scope .............................................................................................................. 2 6 Project Goal ........................................................................................................................ 2 7 Objectives ........................................................................................................................... 2 8 PLANNING EFFORT AND PROCESS .................................................................................. 3 9 Planning Process ................................................................................................................. 3 10 Planning Effort and Criteria for Access Recommendations ............................................... 4 11 How This Plan Relates to Other Plans or Regulatory Systems .......................................... 5 12 ISSUES ..................................................................................................................................... 6 13 Funding Constraints ........................................................................................................... -

Of Kenai Peninsula, Alaska

Series / A' Economic Geology, 65 Bulletin No. 277 series Descriptive Geology) go DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHAELES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR OF KENAI PENINSULA, ALASKA GOLD FIELDS OF THE TURNAGAIN ARM REGION FRED H. MOFFIT. RALPH W. STONE WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1906 CONTENTS. Goui FIELDS OF THE TUKNAGAIN AKM REGION, BY F. H. MOFFIT.... ........ 7 Introduction ..-_........---.-....................................... 1.. 7 ', Location and area ................................................. 7 History............................................... ........... 7 Early explorers .............'................................. 7 Mining....................................:............... 8 Early mining ..........................................'.. 8 Placer development ...................................... 8 Exploration and scientific-investigation ........................ "J.O . Early exploration ........................................ 10 Investigation in 1904 ...................................... 10 Topography.. _........._....................................,.....;.. 12 Shore line ...:..........-......................................... 12 Relief ............................................................ 13 Drainage........................................................ ' 14 General geology...................................................... 16 Sedimentary rocks................................................. 16 Distribution........-.........................;............... 16 Sunrise "series" -

Alaska Earthquake and Tsunami: Consequences of Living on the Leading Edge in Alaska

EarthScope Alaska Native Geoscience Learning Experience Field Trip Guide The 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake and Tsunami: Consequences of Living on the Leading Edge in Alaska May 30, 2018 Field trip leaders: Rob Witter, Robert Butler, Beth Pratt-Sitaula, and Jennifer Witter Perspective view of the Pacific Plate being subducted beneath the North American plate at the Alaska- Aleutian Subduction zone. The pink highlighted region shows the part of the megathrust fault (plate boundary) that slipped in 1964 during the Great Alaskan Earthquake. White arrows show relative plate motion. Red and black bold lines show important faults of the South Central Alaska region. (Source: USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2014/3018/) 1 Field trip stops and driving times Stop Location Arrive Depart Duration Topic 0 ASD Education Center 7:30 am 8 am 30 min Start field trip Drive time: 22 min (8.5 mi) 1 Sunset Park 8:30 am 9:00 am 45 min 1964 earthquake landslides Drive time: 41 min (32 mi) 2 Bird Point 9:45 am 10:45 am 60 min UNAVCO GPS instrument Drive time: 31 min (26 mi) Whittier Tunnel 11:15 am 11:30 am 15 min Tunnel to Whittier Drive time: 8 min (3 mi) 3 Whittier 11:40 am 1:40 pm 2 hrs Tsunami / LUNCH Drive time: 5 min (2 mi) Whittier Tunnel 1:45 pm 2 pm 15 min Tunnel to Girdwood Drive time: 29 min (21 mi) 4 Girdwood Ghost Forest* 2:30 pm 4:15 pm 1 hr 45 m Earthquake evidence Drive time: 43 min (38 mi) 5 ASD Education Center 5ish pm End of field trip *Low tide at Girdwood is around 4:30 pm on May 30, 2018. -

Turnagain Arm Trails

Background photo courtesy of Benjamin Wager Benjamin of courtesy photo Background Fishing at Bird Creek Bird at Fishing Arm Turnagain in whales Beluga salmon in season. in salmon looking to catch silver, pink, and chum chum and pink, silver, catch to looking tedraynor.photoshelter.com Photos courtesy of Ted Raynor Ted of courtesy Photos Bird Creek is a popular location for anglers anglers for location popular a is Creek Bird Bull mooseand Dall’s sheep at McHugh Creek McHugh at sheep Dall’s mooseand Bull Fishing Fishing Photo courtesy of Tim Woody Tim of courtesy Photo Biking Bird to Gird to Bird Biking visit www.alaskatrails.org. www.alaskatrails.org. visit to recreate in Alaska. Alaska. in recreate to your next adventure. For more information information more For adventure. next your Turnagain Arm is one of the most diverse areas areas diverse most the of one is Arm Turnagain Creek Trail. Explore the map inside and find find and inside map the Explore Trail. Creek rock and ice climbing, and fantastic fishing, fishing, fantastic and climbing, ice and rock to Girdwood bike path, and secluded Falls Falls secluded and path, bike Girdwood to water and latrines. and water With rolling bike paths, heart-pounding hikes, hikes, heart-pounding paths, bike rolling With Park including the Bird Ridge Trail, Indian Indian Trail, Ridge Bird the including Park equipped with fire rings, picnic tables, and nearby nearby and tables, picnic rings, fire with equipped popular and scenic trails in Chugach State State Chugach in trails scenic and popular convenient access to bike paths.