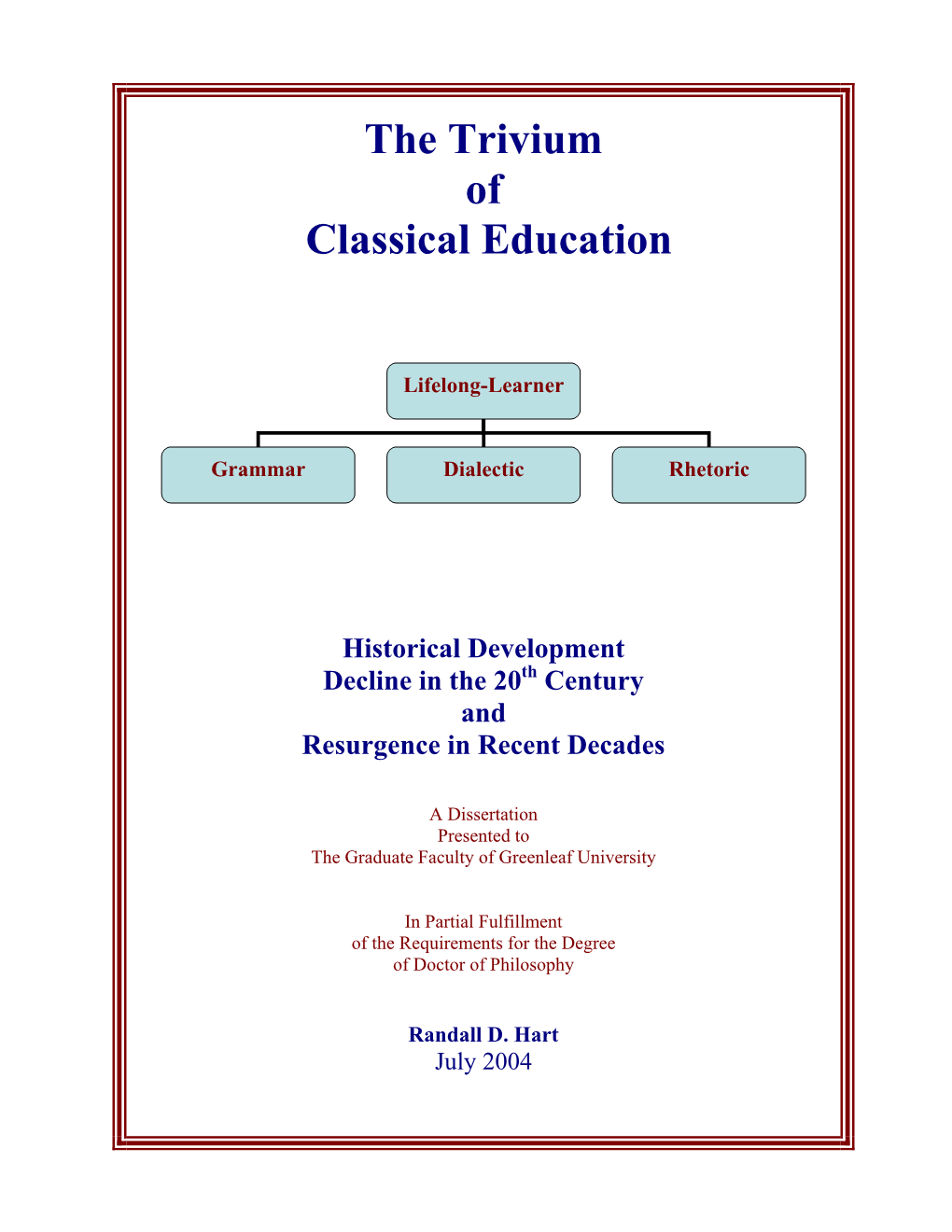

The Trivium of Classical Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-2021 ACADEMIC ALL STATE Division II Aidan Christophe

2020-2021 ACADEMIC ALL STATE Division II Aidan Christophe Saucedo 12 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Zachary Daniel McCalley 11 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Peyton Allen Inderlied 12 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Jackson Dale Herrington 12 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Logan Michael Conklin 12 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Zachary John Ledbetter 12 Coram Deo Academy-Flower Mound Trevor Stegman 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Tyler Williams 11 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Brett Judd 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Matthew Mata 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Kynan Gilreath 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite T.J. King 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Parker Robertson 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Andrew Baucum 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Shon Coleman 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Jacob Hoelzle 11 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Heath Flanagan 11 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Garrett Tillett 12 Dallas Christian School-Mesquite Blaine Brantley Baird 11 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land Cohen Reed Carpenter 12 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land David Richard Kasemervisz 12 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land Ryan Garrett Rudge 11 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land Remington Russell Strickland 12 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land Robert Blaine Walter 12 Fort Bend Christian Academy-Sugar Land Carson James Cross 12 Fort Worth Christian Caden Douglas Blaies 12 Fort Worth Christian Zachary Strickland 12 Fort Worth Christian Houston Buckner 12 Fort Worth Christian Caleb Guy Tackett -

Notes: Definition and Explanation of Trivium and Quadrivium

DEFINITION AND EXPLANATION OF TRIVIUM AND QUADRIVIUM (From the first time I taught the course--my notes) (Communication Education, Vol. 35,#2, April, 1986, 174, Teaching Critical Thinking Skills) In the Middle Ages university courses were divided into two areas, the Arts and the Sciences. These were a system of rules for generating knowledge. The seven Liberal Arts of Languages ( or Arts) and Sciences were complements, and obviously comprised a Liberal Arts education .. TRIVIUM The Languages (ARTS), or Trivium were composed of: Grammar (Latin) Logic Rhetoric These Arts were concerned with (and were to discover) the social significance of knowledge. These Arts were relatively subjective. Completion of this study led to a bachelor's degree. QUADRIVIUM The Sciences, the Quadrivium, was composed of: Arithmetic Geometry Astronomy Music The Sciences arranged knowledge into systematic bodies of information. The Sciences were relatively objective. Completion of the Quadrivium led to a master's degree (Continued Explanation of Trivium and Quadrivium) Rhetoric, chief among the courses of the Trivium, liberated students from a single view of a problem and led them to social autonomy. The divisions of classical rhetoric provide directions forteaching critical thinking skills. Peter Ramus, 1515-1572, redefined ancient discipliines: Beginning with the trivium, with the arts of discourse, Ramus defined grammar as the art of speaking well, that is of speaking correctly; dialectic as the art of reasoning well; and rhetoric as the art of the eloquent and ornate use of language. Skills arising from Invention/inventio/heuristic were insights from researched information and discovery of arguments to support the point of view espoused. -

2020 ACCS Annual Conference | Louisville, Kentucky Jon Balsbaugh Has Over Twenty Years Experience As A

SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES Jon Balsbaugh has over twenty years experience as a high school and junior high teacher and currently serves as the president of Trinity Schools, Inc ., a national network of classically oriented Christian schools dedicated to providing an education that awakens students to the reality of the human condition and the world in which they live . Before taking over as president, he served as the headmaster of Trinity School at River Ridge in Eagan, MN . Mr . Balsbaugh received his master’s degree in English from the University of St . Thomas, studying the theological aesthetics of Hans Urs von Balthasar. He has published on C.S. Lewis and is serving as the editor-in-chief of Veritas Journal, a new online journal of education and human awakening. Jason Barney serves as the academic dean at Clapham School, a classical Christian school in Wheaton, IL. In 2012 he was awarded the Henry Salvatori Prize for Excellence in Teaching from Hillsdale College. He completed his MA in bBiblical exegesis at Wheaton College, where he received the Tenney Award in New Testament Studies . In addition to his administrative responsibilities in vision, philosophy and faculty training, Jason has taught courses in Latin, humanities, and senior thesis from 3rd–12th grades . He regularly speaks at events and conferences, including SCL, ACCS, and nearer home at Clapham School Curriculum Nights and Benefits. Recently he trained the lower school faculty of the Geneva School in Charlotte Mason’s practice of narration in August 2019 . Jason blogs regularly on ancient wisdom for the modern era at www.educationalrenaissance.com, where he has also made available a free eBook on implementing the practice of narration in the classical classroom . -

The Trivium in the 12Th Century

Chapter 7 The Trivium in the 12th Century Frédéric Goubier and Irène Rosier-Catach 1 Introduction In the early 12th century there was no lack of praise for the liberal arts as pathways to acquire wisdom. As we read in Thierry of Chartres’s prologue to the Heptateuchon:1 The two main instruments of philosophical work are understanding (in- tellectus) and its expression in language (interpretatio).The quadrivium illuminates comprehension, and the trivium enables the elegant, ratio- nal, and beautiful expression of comprehension. Thus it is clear that the Heptateuchon constitutes a single, unified instrument for all philosophy. Philosophy is the love of wisdom, and wisdom is the integral comprehen- sion of the truth of existing things, which no one can attain even in part unless he has loved wisdom. The division of knowledge into seven liberal arts was transmitted in the Middle Ages by the encyclopaedists of Late Antiquity: Martianus Capella (De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii,2 ca. 430 or ca. 470 ?), Cassiodorus (Institutiones,3 ca. 620), Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae,4 ca. 625), and then by the authors of the early Middle Ages. The designation liberales appended to artes received various justifications, as one can read in several early 12th-century witnesses: the arts are liberal because they “liberate” the students from sin, in that they prevent their minds from wandering toward perverted behaviour, noted a grammarian named Stephen, or “because they free students from secular worries,” states 1 Édouard Jeauneau, “Le Prologus in Eptatheucon de Thierry de Chartres,” Medieval Studies 16 (1954), 171–175, repr. in Id., Lectio philosophorum: Recherches sur l’École de Chartres (Amster- dam: 1973); Rita Copeland and Ineke Sluiter, Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric (Oxford: 2009). -

Revisiting Renaissance Encyclopaedism

Revisiting Renaissance Encyclopaedism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Blair, Ann. 2013. "Revisiting Renaissance Encyclopaedism." In Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance, edited by Jason König and Greg Woolf, 377-97. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Published Version 10.1017/CBO9781139814683;http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/ catalogue.asp?isbn=9781107454385 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:29675365 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP manuscript for Ann Blair, "Revisiting Renaissance Encyclopaedism," in Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance, ed. Jason König and Greg Woolf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 377-97. Ann Blair, Dept of History, Harvard University Revisiting Renaissance encyclopedism The Renaissance has long been associated with ‘encyclopedism’ primarily for two different reasons which are not directly related to one another. On the hand the term was first coined in the late fifteenth century, though without many of connotations we associate with the term today, to designate an ideal of learning which spanned and highlighted the relations between many disciplines. On the other hand many Renaissance writings, from compilations in various fields to novels and poetry, are considered encyclopedic today because of their large bulk and/or their ideal of exhaustive and multidisciplinary scope. Only occasionally did early modern authors apply the term ‘encyclopedia’ to what we consider their encyclopedic compiling activities, but by the late seventeenth century a handful of works had begun to forge the connection between the term and a kind of reference book. -

Common Core's

THE CLASSICAL VOLUME 2, NUMBER 3 | FALL 2016 BRINGING LIFE TO THE CLASSROOM TM Differ$2.95 ence COMMON CORE’S FIVE-WAY POWER PLAY p. 10 • Fact and Fiction about the CC • Cracking the CC Mission • CC and Your Child’s Love of Learning ALSO... The Amanda Watson Story p. 28 The Fair Market Value of Classical Ed p. 24 Goals for the First 100 Days of School p. 7 ClassicalDifference.com The CLASSICAL The slightest knowledge READER of a great book is better 2 than the greatest A Comprehensive Reading Guide for knowledge of a slight K–12 Students —Aquinas book. Leslie Rayner and Dr. Christopher Perrin n this information age, it’s sometimes hard to know how to choose from the sea of options and resources that present themselves at every turn. When you are choosing what books your Ichildren will read, the stakes are especially high. That is why we have put years of research into The Classical Reader, collecting and analyzing the K–12 reading recommendations of classical educators from around the country, seeking those readings that have been important and pleasurable to generations of students. This pithy book includes recommendations for reading at each grade level, noting each selection’s level of difficulty and genre. The Classical Reader provides a way to keep a record of what your student has read and will also help you to plan future reading. This book is a valuable resource for every school and family for everything from book reports to reading for pleasure. The Classical Reader is a veritable cave of dragon loot, an embarrassment of riches that will provide years of instruction and delight and help to instill a lifelong love of reading. -

Notebook (9MB PDF)

ACCS ANNUAL CONFERENCE THE WEIGHT of GLORY The nations are like a drop in a bucket; they are regarded as dust on the scales. Isaiah 40:15 REPAIRINGthe RUINS.ORG FRISCO (DALLAS), TX T GETHERagain! JUNE 15–18, 2021 GENERAL ANNOUNCEMENTS ❶ Beverages are located in the center of the ven- ❺ If you are a school looking for someone to fill a dor area in Frisco 6. Other food offerings in this position at your school, please leave a 3x5 card hotel are listed among the following pages. with the job description and your contact in- formation on the bulletin board near the regis- ❷ The head of each ACCS-accredited and ACCS- tration booth. Likewise, if you are a “someone” candidate school is invited to join David Good- looking for a position to fill, you may check the win Wednesday in the Bass-Bush room, The bulletin board or post a 3x5 card to let schools meeting begins at 12:15. know of your area of expertise and contact in- formation. Cards may be obtained at the reg- ❸ Each head of school is invited to learn more istration booth. about upcoming ACCS efforts, Thursday in Frisco 8. The meeting will begin at 12:15. ❻ The registration booth will also double as the conference “Lost and Found.” ❹ Please make time to visit each of the ven- dors. We have a large number and broad ❼ Plenary sessions and workshops are being range of vendors at this conference, and we recorded. Member schools will receive full ac- are very thankful for their interest and sup- cess to all conference recordings in the Mem- port. -

Edgard Varese, Modernism, and the Experience of Modernity

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 At the Threshold: Edgard Varese, Modernism, and the Experience of Modernity Robert Jackson Wood Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/130 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] At the Threshold: Edgard Varèse, Modernism, and the Experience of Modernity by Robert Jackson Wood A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 2014 Robert Jackson Wood All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ ________________________________________________ Date Joseph Straus Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ________________________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Richard Kramer Chadwick Jenkins Brian Kane THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract At the Threshold: Edgard Varèse, Modernism, and the Experience of Modernity by Robert Jackson Wood Adviser: Richard Kramer The writings of composer Edgard Varèse have long been celebrated for their often ecstatic, optimistic proclamations about the future of music. With manifesto-like brio, they put forth a vision of radically new instruments and sounds, delineate the parameters for spatially oriented composition, and initiate the discourse of what would become electronic music. -

EXPECTATIONS for the YEAR AHEAD P

THE CLASSICAL VOLUME 5, NUMBER 3 | FALL 2019 BRINGING LIFE TO THE CLASSROOM TM $2.95 GREAT EXPECTATIONS FOR THE YEAR AHEAD p. 4 INSIDE ... All the Rules You Need p. 16 Is Classical Education Worthwhile? p. 14 National Mock Trial Champs— The Agathos Story p. 20 ClassicalDifference.com Leaders see further. At The King’s College in New York City, learn to view history’s greatest questions in the light of eternal Truth. With access to world-class internships and the sup- port of a close-knit, Christ-centered community, gain the discernment that will help you to chart the way for others. THEKINGSCOLLEGE @ See it for yourself at an Inviso Visit Weekend: tkc.edu/accs ADMISSIONSOFFICE@ TKC.EDU | 212-659-7200 | 56 BROADWAY, NEW YORK NY 10004 Table of Contents ON THE COVER: Great Expectations for the Year Ahead .......................4 Is Classical Education Worthwhile ............................. 14 Grace Expectations ....................................................... 16 National Mock Trial Champs ....................................... 20 INSIDE: ClassicalDifference.com Set Apart ............................................................................6 All citations: ClassicalDifference.com/2019-fall Letters & Notes .................................................................9 The Seven Laws of Expecting..................................... 10 Education's Roadblock ................................................ 18 Connect With Us Down the Hallway......................................................... 26 Facebook.com/TheClassicalDifference -

HEAD COACH ACADEMIC CAMP August 15-16, 2020 Frisco, TX HEAD COACH ACADEMIC CAMP

HEAD COACH ACADEMIC CAMP August 15-16, 2020 Frisco, TX HEAD COACH ACADEMIC CAMP Last First Jersey # Team Color / Team Number Last First Jersey # Team Color / Team Number Last First Jersey # Team Color / Team Number Abel Benjamin 7 Green - 14 Gottam Santhosh 7 Purple - 12 Oestrike Jad 7 Burnt Orange - 8 Agarwal Kristopher 11 Purple - 12 Griffith Zane 4 Purple - 12 Olivarez Brandon 3 Teal - 10 Apollaro Anthony 11 Pink - 5 Gutierrez Joseph 8 Neon - 9 O'Shea Ryan 7 Navy - 13 Ardemagni Alex 13 Pink - 5 Hagan Carson 4 Red - 1 Otero Sergio 5 Navy - 13 Arispuro Jorge 6 Royal Blue - 4 Haggard Jack 2 Burnt Orange - 8 Paxson Michael 5 Purple - 12 Armistad Alandas 10 Light Blue - 6 Hamner Aidan 5 Pink - 5 Pellegrino Shane 5 Vegas Gold - 11 Ashcraft Devon 1 Navy - 13 Harris Walker 4 White - 2 Pelter Chase 11 White - 2 Austin George 11 Burnt Orange - 8 Hart Max 14 Purple - 12 Pena Noe 2 Black - 3 Awadzi Bearden 9 Burnt Orange - 8 Hechler Reid 13 Vegas Gold - 11 Pennington William (Trip) 5 Green - 14 Back Ryan 6 Vegas Gold - 11 Henderson Marlon 8 Teal - 10 Peters Jace 3 Pink - 5 Bambakidis Peter 10 Red - 1 Honeyman Alex 9 Pink - 5 Petrazio Raff 12 Royal Blue - 4 Bartlett Connor 10 Olive - 7 Hu William Jon 2 Teal - 10 Pollard Matt 8 Royal Blue - 4 Bazarsky Brett 10 Neon - 9 Huembes Matthew 1 Black - 3 Pope Chase 7 Light Blue - 6 Behrend Ethan 7 Olive - 7 Huffman Jackson 12 Pink - 5 Powell Ryan 3 Burnt Orange - 8 Beiter Jack 6 Burnt Orange - 8 Huhn Tucker 13 Black - 3 Przespolewski Ryan 14 Burnt Orange - 8 Bergman Caleb 2 Royal Blue - 4 Huotari Aiden 4 -

Arnold: Swimming Against the Tide / Boris Khesin, Serge Tabachnikov, Editors

ARNOLD: Real Analysis A Comprehensive Course in Analysis, Part 1 Barry Simon Boris A. Khesin Serge L. Tabachnikov Editors http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/mbk/086 ARNOLD: AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Photograph courtesy of Svetlana Tretyakova Photograph courtesy of Svetlana Vladimir Igorevich Arnold June 12, 1937–June 3, 2010 ARNOLD: Boris A. Khesin Serge L. Tabachnikov Editors AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Providence, Rhode Island Translation of Chapter 7 “About Vladimir Abramovich Rokhlin” and Chapter 21 “Several Thoughts About Arnold” provided by Valentina Altman. 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A65; Secondary 01A70, 01A75. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/mbk-86 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Arnold: swimming against the tide / Boris Khesin, Serge Tabachnikov, editors. pages cm. ISBN 978-1-4704-1699-7 (alk. paper) 1. Arnold, V. I. (Vladimir Igorevich), 1937–2010. 2. Mathematicians–Russia–Biography. 3. Mathematicians–Soviet Union–Biography. 4. Mathematical analysis. 5. Differential equations. I. Khesin, Boris A. II. Tabachnikov, Serge. QA8.6.A76 2014 510.92–dc23 2014021165 [B] Copying and reprinting. Individual readers of this publication, and nonprofit libraries acting for them, are permitted to make fair use of the material, such as to copy select pages for use in teaching or research. Permission is granted to quote brief passages from this publication in reviews, provided the customary acknowledgment of the source is given. Republication, systematic copying, or multiple reproduction of any material in this publication is permitted only under license from the American Mathematical Society. Permissions to reuse portions of AMS publication content are now being handled by Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. -

2021-2022 Family Handbook for Trivium Prep

TRIVIU PREPARATORY ACADEMY A Great Hearts Academy 2021 - 2022 FAMILY HANDBOOK LETTER TO FAMILIES ................................................................................................................................................ 5 OUR MISSION ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 OUR CHARTER, ACCREDITATION, AND AFFILIATIONS .................................................................................... 7 TRIVIUM PREPARATORY ACADEMY’S PHILOSOPHY ........................................................................................ 8 KNOWLEDGE AND THE GREAT BOOKS................................................................................................................................................. 8 UPHOLDING STANDARDS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 10 MORAL VIRTUE ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 10 COMMUNICATION ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 GREAT HEARTS CEO AND MANAGEMENT TEAM ...........................................................................................................................