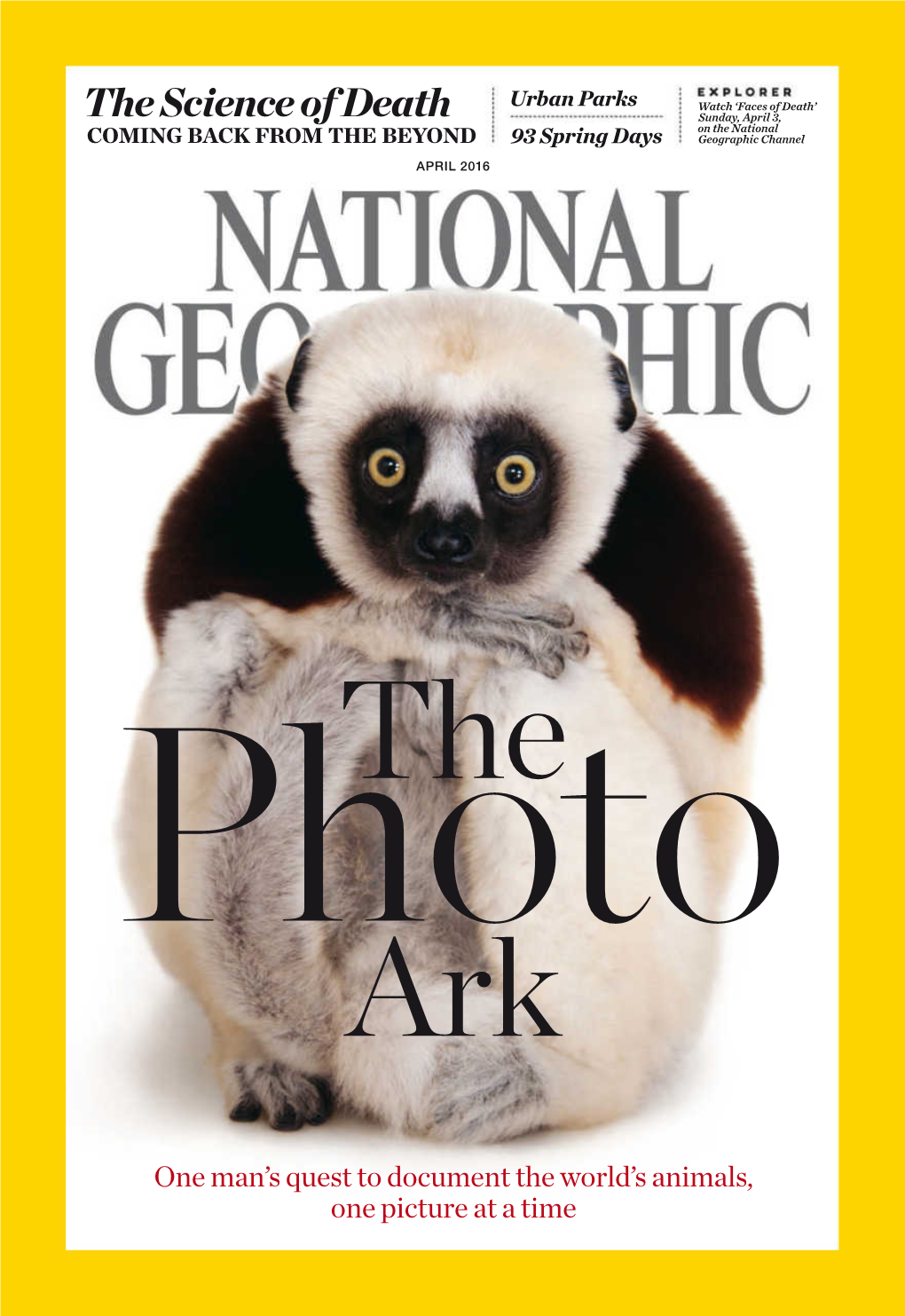

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY from the EDITOR Photo Ark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger T1." Grange, Jr. a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

Ceramic relationships in the Central Plains Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grange, Roger Tibbets, 1927- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 18:53:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565603 CERAMIC RELATIONSHIPS' IN THE CENTRAL PLAINS ^ > 0 ^ . Roger T1." Grange, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Roger T, Grange, Jr»________________________ entitled ______Ceramic Relationships in the Central_____ _____Plains_______________________________________ be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of _____Doctor of Philosophy________________________ April 26. 1962 Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* 5 / ? / ^ t 5 /? / C 2-— A / , - r y /n / *This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination. The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. -

2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts City Name of Attraction

2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts % of Total Summer % of Summer Attendance from Attendance Attendance from Out of State (Memorial Day- Out of State City Name of Attraction Total Attendance Visitors Labor Day) Visitors Omaha Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium 1,700,378 34 774,320 38 Raymond Branched Oak State Recreation Area 1,476,467 Ashland Eugene T. Mahoney State Park 1,155,000 Louisville Platte River State Park 878,020 Fremont Fremont Lakes State Recreation Area 874,300 Lake McConaughy and Lake Ogallala State Recreation Ogallala Areas 821,269 Ponca Ponca State Park 783,707 Louisville Louisville Lakes State Recreation Area 572,000 Chadron Chadron State Park 480,300 Burwell Calamus Reservoir State Recreation Area 472,406 Venice Two Rivers State Recreation Area 436,065 Crawford Fort Robinson State Park 410,560 Lincoln Pawnee State Recreation Area 386,994 Omaha Omaha Children's Museum 290,996 30 104,537 42 Hickman Wagon Train State Recreation Area 259,208 North Platte Lake Maloney State Recreation Area 240,050 Lincoln Haymarket Park 227,600 Shubert Indian Cave State Park 224,450 Pierce Willow Creek State Recreation Area 220,350 Ralston Ralston Arena 215,778 13,633 Lincoln Lincoln Children's Zoo 204,000 11 104,000 12 Omaha The Durham Museum 189,654 22 60,735 28 Omaha Lauritzen Gardens and Kenefick Park 173,130 30 77,552 35 Omaha Joslyn Art Museum 163,324 17 39,307 27 Aurora Edgerton Explorit Center 160,578 15 36,835 20 Nebraska City Arbor Lodge State Historical Park and Arboretum 160,000 Minatare Lake Minatare State Recreation Area 155,312 Wahoo Lake Wanahoo State Recreation Area 143,608 Niobrara Niobrara State Park 130,980 Tekamah Summit Lake State Recreation Area 129,896 2014 Nebraska Attraction Attendance Counts Lexington Johnson Lake State Recreation Area 128,662 Ashland Lee G. -

IMAGINE... the POWER of a PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement

Serving the Photo Community Since 1999 Now offering classes online! IMAGINE... THE POWER OF A PHOTOGRAPH WINTER/SPRING 2021 CONTENTS General Information Mission Statement ......................................................................................... 2 Letter from Julia Dean, Executive Director .......................................... 2 The Board of Directors, Officers and Advisors ........................................... 3 Charter Members, Circle Donors and Donors ................................... 3 Donate ................................................................................................................. 4 Early Bird Become a Member ........................................................................................ 5 Certificate Programs ..................................................................................... 6 One-Year Professional Program ............................................................... 7 Gets the Online Learning Calendar .......................................................................8-9 Webinar Calendar .........................................................................................10 In-Person Learning Calendar ..................................................................11 Discount Mentorship Program ...................................................................................12 Register early for great discounts on The Master Series ........................................................................................13 Youth Program .................................................................................24-25, -

Native American Sacred Sites and the Department of Defense

Native American Sacred Sites and the Department of Defense Item Type Report Authors Deloria Jr., Vine; Stoffle, Richard W. Publisher Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona Download date 01/10/2021 17:48:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/272997 NATIVE AMERICAN SACRED SITES AND THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Edited by Vine Deloria, Jr. The University of Colorado and Richard W. Stoffle The University of Arizona® Submitted to United States Department of Defense Washington, D. C. June 1998 DISCLAIMER The views and opinions expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U. S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of the Interior, or any other Federal or state agency, or any Tribal government. Cover Photo: Fajada Butte, Chaco Culture National Historic Park, New Mexico NATIVE AMERICAN SACRED SITES AND THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Edited by Vine Deloria, Jr. The University of Colorado and Richard W. Stoffle The University of Arizona® Report Sponsored by The Legacy Resource Management Program United States Department of Defense Washington, D. C. with the assistance of Archeology and Ethnography Program United States National Park Service Washington, D. C. June 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables vii List of Figures ix List of Appendices x Acknowledgments xii Foreward xiv CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Scope of This Report 1 Overview of Native American Issues 3 History and Background of the Legacy Resources Management Program 4 Legal Basis for Interactions Regarding -

The Massacre Canyon Battle Are Found Below: One Is by a Chicago Tribune Reporter Writing out of Omaha, and the Other Is a 1922 Account by John W

The term “Indian Wars” usually refers to battles and skirmishes that occurred between the United States army and various Native American tribes in the second half of the 19th century. But long before Europeans arrived in the Americas, Indians had been engaging in savage inter-tribal warfare. It is no exaggeration to say that tribal warfare was an integral part of Indian culture. There is no way to know when the first large battle between Indian tribes occurred in North America, but the last great battle was fought in southwest Nebraska between the Sioux and the Pawnees. It happened on August 5, 1873, and was actually more of a massacre than a battle. The two most riveting sources on the Massacre Canyon Battle are found below: one is by a Chicago Tribune reporter writing out of Omaha, and the other is a 1922 account by John W. Williamson, the white trail agent for the Pawnees, who witnessed and participated in the battle. The Massacre Canyon Battle From The Chicago Daily Tribune; August 30, 1873; page 2; written by reporter Aaron About and sent from Omaha, Nebraska, on August 25. On the 8th of August, Conductor Norton, who came down on the western passenger train of the Union Pacific Road, announced that a “great battle” had been fought between the Sioux and Pawnee Indian tribes, on the Republican, 150 miles south of Elm Creek. Mr. Norton said several Indians had come into his train at Grand Island, and told a pitiful story of the battle. Little attention was paid to the report, people believing the Pawnees…had overrated the fight, and that the whole affair would in a few days settle down into a small skirmish. -

Educator Resource Guide Table of Contents

EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS ANNENBERG SPACE FOR PHOTOGRAPHY 03 HISTORY • EXHIBITS • DESIGN • DIGITAL GALLERY THE CURRENT EXHIBIT: THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC PHOTO ARK 04 AGE RECOMMENDATION • OVERVIEW 05 BIOGRAPHY OF PHOTO ARK FOUNDER JOEL SARTORE EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE 06 PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY 08 PRE-VISIT ACTIVITY TWO 11 EXHIBITION ACTIVITY 12 POST-VISIT ASSIGNMENT © 2009 JULIUS SHULMAN & JUERGEN NOGAI 15 POST-VISIT ASSIGNMENT TWO 18 APPENDICES 02 ANNENBERG SPACE FOR PHOTOGRAPHY HISTORY • EXHIBITS • DESIGN HISTORY Annenberg Space for Photography opened to the public on March 27, 2009. It is the first solely photographic cultural destination in the Los Angeles area. The Photography Space is an initiative of the Annenberg Foundation and its board of directors. Its creation builds upon the Foundation’s long history of supporting the visual arts. 20mm 225.5mm 47.6mm 225.5mm 20mm Lauren Greenfield Lauren Lauren Greenfield Generation Wealth THE THE APR 21 – SEPT 9 Timothy Green eld-Sanders’ BLACK LATINO Generation Wealth Generation List Series calls attention to IDENTITY: Timothy Green eld-Sanders people who have overcome The List Portraits is comprised of 151 large- The Annenberg Space for Photography is a cultural destination dedicated to exhibiting compelling photography. The Photography Space conveys a range of human obstacles to achieve THE PREMIERING experiences and serves as an expression of the philanthropic work of the Annenberg Foundation. The intimate environment presents digital images via high- LIST defi nition digital technology as well as traditional prints by both renowned and emerging photographers. The Photography Space informs and inspires the public by format photographs of pioneers in historically success in disparate walks LIST connecting photographers, philanthropy and the human experience through powerful imagery and stories. -

National Council of State Tourism Directors State Travel Counselor Certification Program Exam

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE TOURISM DIRECTORS STATE TRAVEL COUNSELOR CERTIFICATION PROGRAM EXAM TEST A ANSWERS 2014 Travel Season 2 Name: _______________ANSWERS__________________________________ Score: _______ E-mail Address: __________________________________________________________________ To become a certified state travel counselor through the U.S Travel Association’s National Council of State Tourism Directors, applicants must take and pass this certification exam with a minimum score of 85%. This exam consists of 100 questions. Nebraska Geography (23 questions) 1. Approximately how many square miles are in Nebraska? A. 77,000 B. 72,500 C. 79,000 D. 81,250 2. What are Nebraska’s two largest cities? Omaha and Lincoln 3. Approximately how many lakes are in Nebraska? A. 2,500 B. 1,750 C. 2,000 D. 2,900 4. Name the six states that border Nebraska? South Dakota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming 5. The Nebraska National Forest at Halsey is the world’s largest hand-planted forest. True False 6. The time zone change occurs between which two exits on Interstate 80? A. Sutherland/Roscoe B. Hershey/Brady C. Sutherland/Paxton D. Brady/Maxwell 7. What and where is Nebraska’s highest point? Panorama Point, Kimball County 8. Identify the area of the state generally known as the Sandhills. Western and Central Nebraska 9. Nebraska has more miles of rivers than any other U.S. state? True False 10. Which two Nebraska counties are named after animals? Antelope, Buffalo 11. Which Nebraska community lies equidistant between Boston and San Francisco? A. Grand Island B. Kearney C. Hastings D. Lexington 12. What is the largest body of water in Nebraska? Lake McConaughy 13. -

AUTHOR AVAILABLE from the Pawnee Experience

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 235 934 RC 014 310 AUTHOR Solberg, Chris; Goldenstein, Erwin, Ed. TITLE The Pawnee Experience: From Center Village to Oklahoma (Junior High Unit). INSTITUTION Nebraska Univ., Lincoln. Nebraska Curriculum Inst. on Native American Life. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 80p.; For related document, see RC 014 309. AVAILABLE FROMNebraska Curriculum Development Center, Andrews Hall 32, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 0336 ($2.00). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teab ers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01\Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS., DESCRIPTORS *American Indian History; American Indian Literature; American Indians; *American Indian Studies; ChronicleS; *Cultural Background; Cultural Education; Cultural Influences; Economic Change; Historiography; Junior High Schools; Kinship; *Learning Modules; *Life Style; Perspective Taking; Primary Sources; *Relocation; Tribes; United States History; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Pawnee (Tribe) ABSTRACT A sample packet on the Pawnee experience, developed for use by junior high teachers, includes a\reading list and materials for teachers and students. Sections on Pawnee origins, history, religion and world view, tribal structure and kinship, and economic system before and after relocation from Nebraska to Oklahoma include objectives, lists of materials needed, exercises for students, and essays accompanied by questions to ponder. For _-i-n-stance, the section on Pawnee origins has the following objectives: (1) introducing students to Pawnee accounts of their origins and encounters with Europeans, and to the notion that different people interpret hist6ry differently, according/to their values and history; and (2) showing students that the meaning of history depends in part on the symbolism people carry into a historical event. -

The Transformative Ark

Chapter 15 The Transformative Ark Ben A. Minteer and Christopher Rojas Abstract As conservationists confront an accelerating extinction crisis, zoos are emerging as potentially significant players in the effort to protect global biodiver- sity, a role that will likely intensify in the coming decades. It’s an agenda, however, that raises a number of ethical and practical questions as zoological parks seek to balance a growing conservation mission alongside their traditional recreation and entertainment pursuits. Many of these questions were first addressed in Bryan Norton’s anthology, Ethics on the Ark, a milestone in applied ethics and zoo conservation published in 1995. In the decades since Norton’s book appeared, the function of zoos as conservation educators and as centers of public transformation has come into sharper focus, with new fields such as conservation psychology measuring the impact of the zoo visit on public perceptions, attitudes, and con- servation behaviors. In this chapter, we explore some of this recent empirical work examining zoo visitors’ experiences and argue that Norton’s early writing in environmental ethics and conservation, particularly his notion of “transformative value,” offers a philosophical grounding for understanding the ethical potential of encounters with zoo animals. We close the chapter by discussing some of the challenges and tensions that emerge when Norton’s argument, which was originally presented as a justification for protecting wild biodiversity due to its ability to “transform” consumer preferences to more ecologically enlightened attitudes, is adapted to the zoo setting. Keywords Zoos Á Conservation education Á Transformative value Conservation psychology B. A. Minteer (&) School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, P.O. -

Attenborough at 90 Premieres • Baby Makes 3 Returns • Young Writers

08/2017 Attenborough at 90 Premieres • Baby Makes 3 Returns • Young Writers Winners! This month, the acclaimed documentary series POV presents Raising Bertie, a coming-of-age story set amid the realities of rural North Carolina. Such important, award-winning programs are made possible through the support of viewers like you during our August Fundraiser on UNC-TV—PBS & More! aboutUNC-TV CenterPiece is the monthly program guide of 2017 UNC-TV, North Carolina’s public media network and broadcast service licensed to the University UNC-TV of North Carolina. Contributions are tax deduct- ible to the extent permitted by law. UNC-TV’s WINNERS central offices and studios are housed in the Joseph and Kathleen Bryan Communications Our judges had a tough job picking the top three finishers Center in Research Triangle Park. from all the wonderful submissions, but congratulations go out to the following kids! Check out animated versions 10 TW Alexander Drive PO Box 14900 this fall at unctv.org/kids/contest. Thanks to all the talented Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-4900 writers and illustrators who submitted stories! 1-919-549-7000 or 1-800-906-5050 Kindergarten UNC-TV network stations are: Asheville WUNF-TV 1st Place: Arielle R., Pikeville Canton/Waynesville WUNW-TV 2nd Place: Aarnavi B., Morrisville Chapel Hill/Raleigh/Durham WUNC-TV Charlotte/Concord WUNG-TV 3rd Place: Silas L., Louisburg Edenton/Columbia WUND-TV 1ST GRADE Greenville WUNK-TV Jacksonville WUNM-TV 1st Place: Felix G., Apex Linville WUNE-TV 2nd Place: Shannon C., Indian Trail Lumberton WUNU-TV Roanoke Rapids WUNP-TV 3rd Place: Klara E., Greensboro Wilmington WUNJ-TV 2ND GRADE WUNL-TV Winston-Salem Illustration by: Haroon Rasheed Z. -

Federal Register/Vol. 64, No. 232/Friday, December 3, 1999

67932 Federal Register / Vol. 64, No. 232 / Friday, December 3, 1999 / Notices offices in Lakewood, Colorado. aggressive and comprehensive audit Bull (Sioux) from Pawnee Indian (sic) in Individual respondents may request that program. To be considered for a the last battle between those nations.'' we withhold their home address from cooperative agreement, States and Consultation with representatives of the the rulemaking record, which we will Tribes must comply with the regulations Pawnee Indian Tribe of Oklahoma honor to the extent allowable by law. at 30 CFR part 228 by submitting a indicates this battle was probably at There also may be circumstances in request to the Director, MMS, and Massacre Canyon near Trenton, NE. No which we would withhold from the preparing a proposal detailing the work evidence exists to contradict this rulemaking record a respondent's to be done. While working under a information. identity, as allowable by law. If you cooperative agreement, the States and Based on the above mentioned wish us to withhold your name and/or Tribes must submit quarterly vouchers information, officials of the Carnegie address, you must state this to claim reimbursement for the cost of Museum of Natural History have prominently at the beginning of your eligible activities. determined that, pursuant to 43 CFR comment. However, we will not We have cooperative agreements with 10.2 (d)(1), the human remains listed consider anonymous comments. We seven Indian Tribes and ten States. above represent the physical remains of will make all submissions from Burden estimates for participants one individual of Native American organizations or businesses, and from include application preparation, ancestry. -

Nebraska Heritagetourismplan

NEBRASKA HERITAGE TOURISM PLAN Prepared for: Division of Travel and Tourism, Nebraska Department of Economic Development September 2011 Nebraska Heritage Tourism Plan National Trust for Historic Preservation UNL Bureau of Business Research Prepared by: Bureau of Business Research, Department of Economics College of Business Administration, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Eric Thompson, Associate Professor and Director Jamie Kezeor Eric Ransom About the Bureau of Business Research: The Bureau of Business Research is a leading source for analysis and information on the Nebraska and Great Plains economy. The Bureau conducts both contract and sponsored research on the economy of states and communities including: 1) economic and fiscal impact analysis; 2) models of the structure and comparative advantage of the current economy; 3) economic, fiscal, and demographic outlooks, and 4) assessments of how economic policy affects industry, labor markets, infrastructure, and the standard of living. The Bureau also competes for research funding from federal government agencies and private foundations from around the nation and contributes to the academic mission of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln through scholarly publication and the education of students. The Bureau has conducted economic studies for a variety of key Nebraska cultural or tourism institutions including the University of Nebraska Athletic Department, Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo, the Nebraska wine industry, the Rowe Sanctuary, and the Olympic Swim Trials. The Bureau website address is www.bbr.unl.edu. Heritage Tourism Program National Trust for Historic Preservation Amy Webb, Heritage Tourism Program Director About the Heritage Tourism Program: The National Trust for Historic Preservation launched the Heritage Tourism Program in 1989.