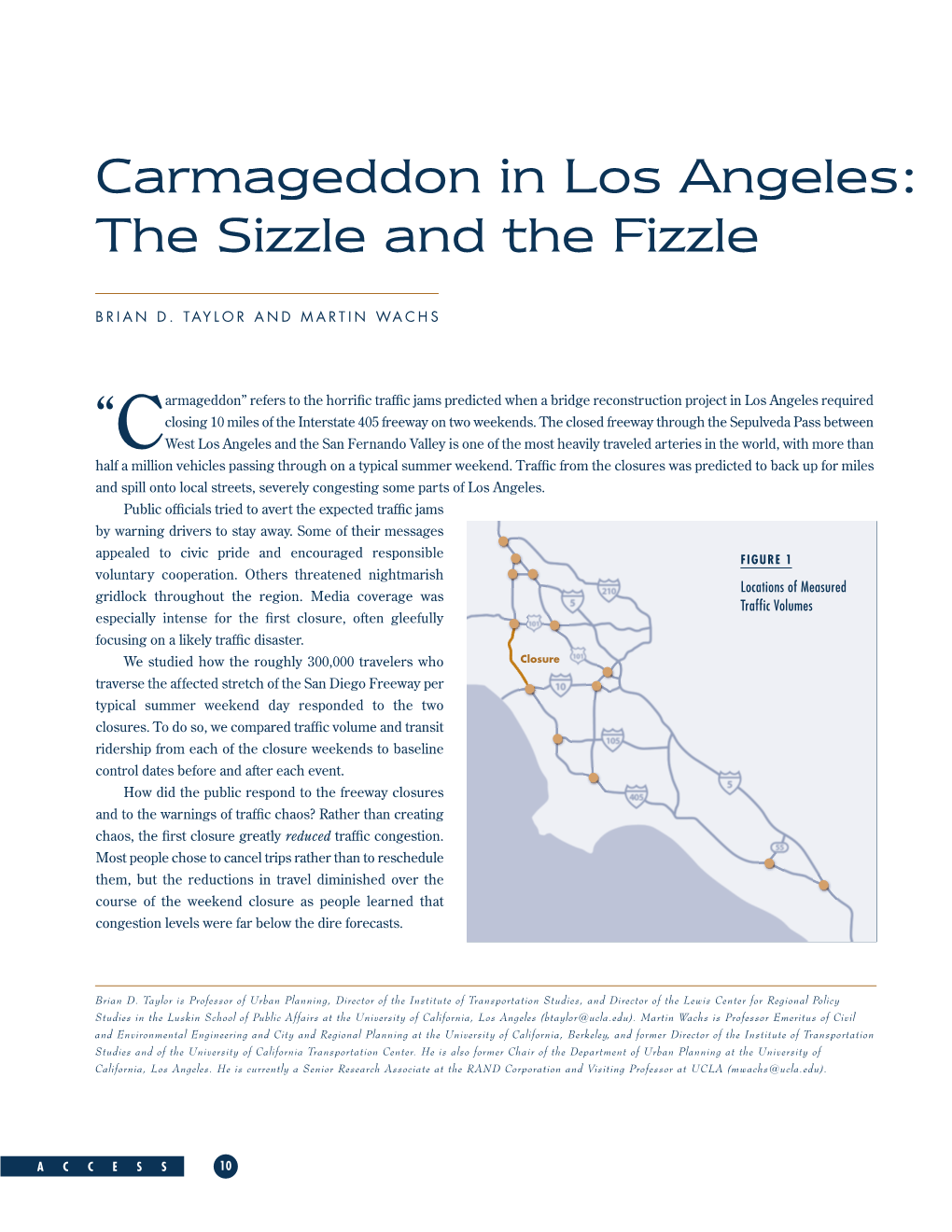

Carmageddon in Los Angeles: the Sizzle and the Fizzle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Mirror

Campus Mirror Published During the College Year by Students of Spelman College, Atlanta, Georgia VOL. XXIV October - November, 1948 NO. 2 THANKSGIVING RALLY "... BIRTH NIGHT OF OUR LORD” Carols Theme This Year: ring out and songs of praise swell the air as the Atlanta-Morehouse- Spelman chorus makes ready for the Twenty-Second Annual Christmas Carol Give ’til You Help Concert on Friday and Saturday nights, December 17th and 18th, 1948, in the beautiful Sisters’ Chapel at Spelman College. Each year the chorus, under the The Thanksgiving Committee chal¬ direction of Professor Kemper Harreld, lenged Spelman this year by emphasiz¬ gives to the community of Atlanta Uni¬ ing not only class competition but also versity and the city of Atlanta, songs individual gifts. It was hoped that that fill the heart with “the wondrous through bulletins, posters, and chapel news.” The Morehouse and Spelman College glee clubs will contribute notes speakers, this could be accomplished. of interest to this international song Numerous organizations and classes fest. heeded their call. The concert will open with an organ For instance: classes gave varied prelude of Irish origin. This composi¬ forms of entertainment in order to tion, “The Christmas Pipes of Country Clare”, is one of Irish carolry tunes of raise their contribution (with the ex¬ 1680 to 1730 arranged by Harvey Gaul. ception of the freshman class). All The traditional processional, “0 Come, classes asked for individual sacrifices. 0 Come, Emmanuel”, which is thir¬ The senior class presented a Sadie Haw¬ teenth century plain song, will be used. This is to be followed by carols which A I kins festival; the Junior class gave two Secret Can Share are Swedish, Russian, Greek, Catholic, movies; and the sophomore class spon¬ A capturing smile, a pleasing per¬ Old English, Czech, American arranged, sonality, and a voice of authority— sored a waistline party. -

Can You Predict a Hit?

CAN YOU PREDICT A HIT? FINDING POTENTIAL HIT SONGS THROUGH LAST.FM PREDICTORS BACHELOR THESIS MARVIN SMIT (0720798) DEPARTMENT OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE RADBOUD UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN SUPERVISORS: DR. L.G. VUURPIJL DR. F. GROOTJEN Abstract In the field of Music Information Retrieval, studies on Hit Song Science are becoming more and more popular. The concept of predicting whether a song has the potential to become a hit song is an interesting challenge. This paper describes my research on how hit song predictors can be utilized to predict hit songs. Three subject groups of predictors were gathered from the Last.fm service, based on a selection of past hit songs from the record charts. By gathering new data from these predictors and using a term frequency-inversed document frequency algorithm on their listened tracks, I was able to determine which songs had the potential to become a hit song. The results showed that the predictors have a better sense on listening to potential hit songs in comparison to their corresponding control groups. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 1 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................ 2 2.1 MUSIC INFORMATION RETRIEVAL ................................................................................................. 2 2.2 HIT SONG SCIENCE ........................................................................................................................... -

Rochelle Una Frankie Mollie Vanessa

Mollie Rochelle Frankie Vanessa Una 00 BEAUTY HAPPY They are usedDAYS to selling out stadiums and belting out chart-topping hits, but how do The Saturdays ensure they look good in the spotlight? We joined the girls backstage on their Greatest Hits Live! tour to find out Trying to get a word in edgewise when we would normally, and we have quick changes, where chatting to the five Saturdays stars is quite an our make-up and hair and wardrobe people are achievement. There is baby news from second-time backstage to get us quickly in to our next outfits.” mother-to-be Una Foden, Strictly Comes Dancing gossip Frankie: “And we all have our own lip glosses, powder from the newlywed Frankie Bridge, who is a contestant and make-up with our names on them, lined up to on the latest series, fashion and beauty chatter from quickly apply as we get changed.” Vanessa White and Mollie King, who are both signed Rochelle: “Frankie is the master of the quick change – with modelling agencies, and TV tips from Rochelle she can get dressed really quickly so she has more time Humes, who has enjoyed a stint as a This Morning for her make-up.” presenter alongside her pop star husband Marvin. Mollie: “I’m always last out – running – while Frankie There is no doubt that The Saturdays are a multi- is sitting back waiting. Every second counts.” tasking creative collective, and it’s also obvious from spending time with them during their recent Greatest Any costume mishaps? Hits Live! tour that they are not only band mates but Rochelle: “Oh yes! My zip wouldn’t do up. -

Jingle Bell Ball Tickets for Jingle Bell Ball 2010 Available

Nov 03, 2010 11:08 GMT Jingle Bell Ball Tickets for Jingle Bell Ball 2010 available Jingle Bell Ball is a concert held every year in December, by 95.8 Capital FM at London’s O2 Arena. Headline acts have included Rihanna, Lady Gaga and Janet Jackson so far. Jingle Bell Ball is hosted by 95.8 Capital FM presenters Johnny Vaughan, Lisa Snowdon, Richard Clarke and Kat Shoob. A portion of ticket sales profit is donated to Help a London Child, 95.8 Capital FM's flagship charity. 95.8 Capital FM’s Help a London Child is a grant giving charity, which provides practical and lasting support to thousands of youngsters aged 18 and under. Jingle Bell Ball was first time held on 8 December 2008, sponsored by the London Lite and Zavvi; and Rihanna was the headline act for it. Jingle Bell Ball 2008 line-up also included: The Pussycat Dolls, Boyzone, Will Young, The Script, The Saturdays, Anastacia, Craig David, Sugababes, Lemar, Alphabeat, Scouting for Girls, Enrique Iglesias, James Blunt, James Morrison and Gabriella Cilmi. Jingle Bell Ball 2009 saw the event span to 2 days and was held on 5-6 December 2009. Lady Gaga headlined the 5 December 2009, sponsored by Windows 7, which also featured Miley Cyrus, Jordin Sparks, Noisettes, Taio Cruz, Tinchy Stryder, JLS, Pixie Lott, Chipmunk, Sugababes, The Saturdays, Westlife, N-Dubz and Jedward. Janet Jackson was the headliner on the 6 December 2009; while JLS, Shakira, Dizzee Rascal, Alexandra Burke, Backstreet Boys, The Veronicas, Flo Rida, Esmée Denters, Metro Station, Agnes Carlsson, Ne-Yo, La Roux, Alesha Dixon and Jedward also featured. -

Positive Stories – Rosie

Rosie’s story Ever since I was a child, difference has always surrounded me. I’ve always been very tall and if you add to that a mix of clumsiness and lack of coordination, it made me stand out like a sore thumb. I was always the one who was last at sports day, the person nobody wanted on their team. I could trip up over thin air and I always seemed to have half my artwork down my top rather than on the paper. It made me feel very self-conscious and insecure and I used to stoop to hide my tallness. All this made me a victim for bullies. My mum had a huge fight to get me proper help with my dyspraxia, even though I was diagnosed when I was four. The teachers at my primary school told her she was an overprotective parent and that I was “too clever” to be struggling. It was then that I decided that I didn’t want others to feel or go through what I had. I started doing work for the Dyspraxia Foundation to raise awareness and to get these often hidden conditions talked about. I started interacting on social networks with other organisations and people who had been through similar problems. I also helped Mollie King from girl band The Saturdays win an inspirational dyslexia award two years in a row, and helped raise over £550 as part of a campaign for her birthday. In June, I was lucky enough to be able to present Mollie with her award. -

James F. Reynolds Years Ago

Craft album. “I’ve always got a kick out of artist development,” says Reynolds. He has been in the building in Parsons Green for about 15 years, and moved into his current room about 8 James F. Reynolds years ago. When Resolution visited, Reynolds was finishing mixes for self-recording multi- The mixer collaborated with K-Pop’s biggest act and US #1 instrumentalist Youngr and had recently mixed new material by James Smith, Oh Wonder, BTS. GEORGE SHILLING visits his West London mix room Swedish soul singer Sabrina Ddumba and also to find out more about sound for the East London-born artist Sinéad Harnett for her shortly to be released album and single. s a teenager, James F. Reynolds was an avid blues harmonica player, and following a leg injury he spent a year A at his parents’ home in Jersey, writing music with their grand piano. After buying a couple of mics to record himself he studied at Gateway School to learn how to do it properly, then landed a job writing and producing dance music at Hit House Studio in Hammersmith. Previously part of duo Public Symphony (“Floyd meets Coldplay”) who performed live supporting Jason Mraz, Reynolds is now mainly known for his mixing work. Notable clients have included Paloma Faith, Calvin Harris, Ellie Goulding, Years And Years, Sigrid, Emeli Sandé, The Vamps, The Saturdays and BTS. Recently he has also started managing artists including Marcus McCoan and Arcades. Reynolds put the two members of Arcades together and now co-manages them with Nick Gatfield; both acts are signed to Gatfield’s Twin label and Reynolds has written material for both. -

Fourth QTY 2018 FINAL Screen Version

FOURTH QTR 2018 HOT TOPICS “Salem Saturdays in Autumn” & “Salem Saturdays at Christmas” Pilot 2018 PROGRAMS ANALYSIS • 37 Public Programs Old Salem began a pilot project of marketing • 100% of the programs were revenue producing and covered internal costs. Saturdays as special days of visitation and • 34% higher-than-projected revenue for 2018 Public Programs (2018 Net Revenue of experiences. The pilot ran from September 22, 2019, $155K vs. $117K projected). through December 29, 2018. In comparing “Salem • Out of 65 programs submitted for review, 38% of the submitted programs projected a Saturdays” 2018 to the Saturdays of 2017 during the same time period, we found the following: loss of $33,000 and thus were removed from the 2018 schedule. • • 50% overall increase in ticketed visitors on 2018 This Assessment EXCLUDES “Salem Saturdays in Autumn” and “Salem Saturdays at “Salem Saturdays over 2017 of same time frame. Christmas” (see details elsewhere in this update). • 80% of the 2018 “Salem Saturdays” dates INCOME & EXPENSES AT A GLANCE surpassed 2017 Saturday attendance of same time • frame. Comparing the prior year’s net income, we trail 2017 by 14%; however, we are exceeding 2016 and 2015 by 14% and 32% respectively. • 3.5% decrease in retail sales on 2018 Saturdays vs. • We have lowered our expenses YTD by 10% compared to budget and 2017. 2017. • Expenses are down by 18% compared to 2016, and 23% compared to 2015. • OSMG YTD as of November 30th net income is lagging behind the approved 2018 budget by 33%. Halloween 2018 PRELIMINARY 2018 DEVELOPMENT RESULTS Overall Development NET 2018 compared to four-year average: (-6%) Overall Development Expense 2018: (Reduced expenses by 29% from 2017) Pillars Corporate memberships: 24% increase in gross revenue from 2017 OSMG Individual Donations: 13% increase in gross individual donations over normal 2017 contribution cycle. -

Frankie Bridge

lifestyle SUNDAY, MAY 29, 2016 Gossip splashes out $28m Lopez on new Bel Air home he 46-year-old actress and singer bought the eight-acre estate - ule to run at The Axis at Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino until December which comes with a lake and a beach - from actress Sela Ward, who and while it has been a huge success so far, she admitted that when she Toriginally wanted $40 million for the property. TMZ also reports that performed the whole thing together for the first time with her dancers, the house is 13,000 square feet and can be accessed by walking across a they ended up throwing up. She said: “I love what I do. When I put it covered bridge. Last year Jennifer put her Hidden Hills home on the mar- together, I thought I’d put it together section by section and then I ket for $17 million but dropped the price to $12.5m earlier this year. She thought this is a great section, this is a great section, this is a great section. originally snapped the home up in 2010 for $8.2 million when she was still “And then all of a sudden we had all these sections and when we did them married to Marc Anthony. Jennifer reportedly first decided to sell the prop- back to back all the dancers were throwing up and it was so hard and I was erty because it was too far from the studios she was taping ‘American Idol’ like, ‘Oh my God! What have I done?’ But then everybody was like, ‘It’s in. -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

P36-40 Layout 1

lifestyle TUESDAY, APRIL 18, 2017 GOSSIP Una Healy wants dance tracks na Healy is ready to become an EDM star. The former but it won't be for a few years. "I really miss the girls and their com- Saturdays singer's debut solo album, 'The Waiting Game' pany. We're all doing out own thing, but I've got the guys in the Uhad a country and folk vibe but she is keen to try some- band now. But of course I miss the girls." Despite this, Una insisted thing radically different in the future. She told BANG Showbiz: she was relishing the experience of being a solo artist, explaining it "I'd love to work with someone like Sigala or Jonas Blue. I love gives her the opportunity to indulge her own specific tastes in dance music and I'll often hear a track and think I wish I could music. She added: "It's so me, totally. The whole album is about my write a top line on that. And then a few weeks later it's in the life ... now it's unleashed to the world. I feel I've done a full circle. "I charts because someone's written a top line on it ... I just love was embarking on the path of a singer songwriter. Going around writing melodies and lyrics." The 35-year-old beauty recently pubs and clubs, then I joined the Saturdays and it was a huge admitted she is keen to reunite with the Saturdays - who change for me. It's like being given a second chance to go back to went on hiatus in 2014 - eventually but doesn't think it'll be the music I like." in the near future. -

Leah's Song List

Leah’s Song List Ballads Pop songs All I wanna do is make love to you- Heart A Sky Full Of Stars- Coldplay All of me- John Legend Alarm- Anne Marie Ave Maria- Beyonce All About That Bass- Meghan Trainor Beneath Your Beautiful- Labrinth & Emeli Sande Applause- Lady Gaga Clown- Emeli Sande Baby love- The Supremes Don’t let go- En Vogue Bad Romance- Lady Gaga Don’t You Worry Child (acoustic) Bang Bang- Jessie J, Ariana Grande & Nikki Minaj Flashlight- Jessie J Be the one- Dua Lipa Hallelujah- Alexandra Burke Best Behaviour- Louisa Johnson Halo- Beyonce Black Magic- Little Mix Hello- Adele Blow Me (one last kiss)- Pink Hometown Glory- Adele Body On Me- Rita Ora Hurt- Christina Aguilera Can’t stop the feeling- Justine Timberlake I’m Not The Only One- Sam Smith Chained to the rhythm- Katy Perry Love Me Like You Do- Ellie Goulding Change your life- Little Mix Love The Way You Lie Part II- Rihanna Chao Adios- Anne Marie Make You Feel My Love- Adele Cheap Thrills- Sia Never Let Me Go- Lana Del Rey Circus- Britney Spears Over and Over again- Nathan Sykes Cool For the Summer- Demi Lovato Read All About It- Emeli Sande Cool Girl- Tove Lo Secret Love Song- Little Mix Counting Stars- One Republic Somewhere over the rainbow- Eva Cassidy Crazy In Love- Beyonce Songbird- Eva Cassidy Crazy- Knarles Barkley Stay- Rihanna Dancing on my own- Robyn Stay With Me- Sam Smith Dear Darlin- Olly Murs Stop- Sam Brown Diamonds- Rihanna Think Twice- Celine Dion Disturbia- Rihanna Thinking Out Loud- Ed Sheeran DJ Got us falling in love- Usher Titanium (acoustic) Do -

DISCOGRAPHY Alex Beitzke Producer, Mixer, Engineer

Reimersbrücke 5 20457 Hamburg DISCOGRAPHY Tel: 040 / 28 00 879 - 0 Fax: 040 / 28 00 879 - 28 Alex Beitzke mail: [email protected] producer, mixer, engineer Platin Award James Arthur "Say you won't let go" (8x) P: Producer E: Engineer M: Mixer R: Remixer Co-W: Co-Writer W: Writer ED: Editor Pro: Programmer A: Arrangement Year Artist Title Project Label Credit 2021 Cobi "Pour One For Me" Single Manitou River Records M Scott Quinn "Better for me" EP gentle giant records M Scott Quinn "Holding on to Letting Go" Single gentle giant records P, M Co-P, Co- Tim Schou feat. Sowfy "Mad Love" Single Iceberg Records W, M Scott Quinn "Better for Me" Single Gentle giant records M Tyler Shaw "When You're Home" Single Sony Music Co-W 2020 Cobi "Go 2 Sleep" Single 300 Entertainment M Scott Quinn "Nightmare" Single gentle giant records M B1 Recordings / Sony Rhodes "Every Turn" Single Co, M Music B1 Recordings / Sony Rhodes "I'm Not Okay" Single Co-P Music Cobi "Don't Stop" Single 300 Entertainment Co-P, M B1 Recordings / Sony Rhodes "This Shouldn't Work" Single Co-P Music Co-P, Honey Harper "Starmaker" Album ATO Records/PIAS Co-W Cobi "Keep Climbing" Single 300 Entertainment P, M Cobi "No Way Out" Single 300 Entertainment M 2019 Cobi "Island in my mind" Single 300 Entertainment P, M James Arthur "You" Albumtracks Columbia Records Co-W,P,M Lighthouse Family "Blue Sky In Your Head" Album Universal Music P James Arthur "Falling Like Stars" Single Columbia Records P, M Game of Thrones "Game of Thrones" Albumtrack Columbia Records Vocal P 2018 Kilian&Jo feat.Prof X&ASDIS "Higher" Single Virgin/Universal Music add.