Sialolithiasis: Traditional and Sialendoscopic Techniques

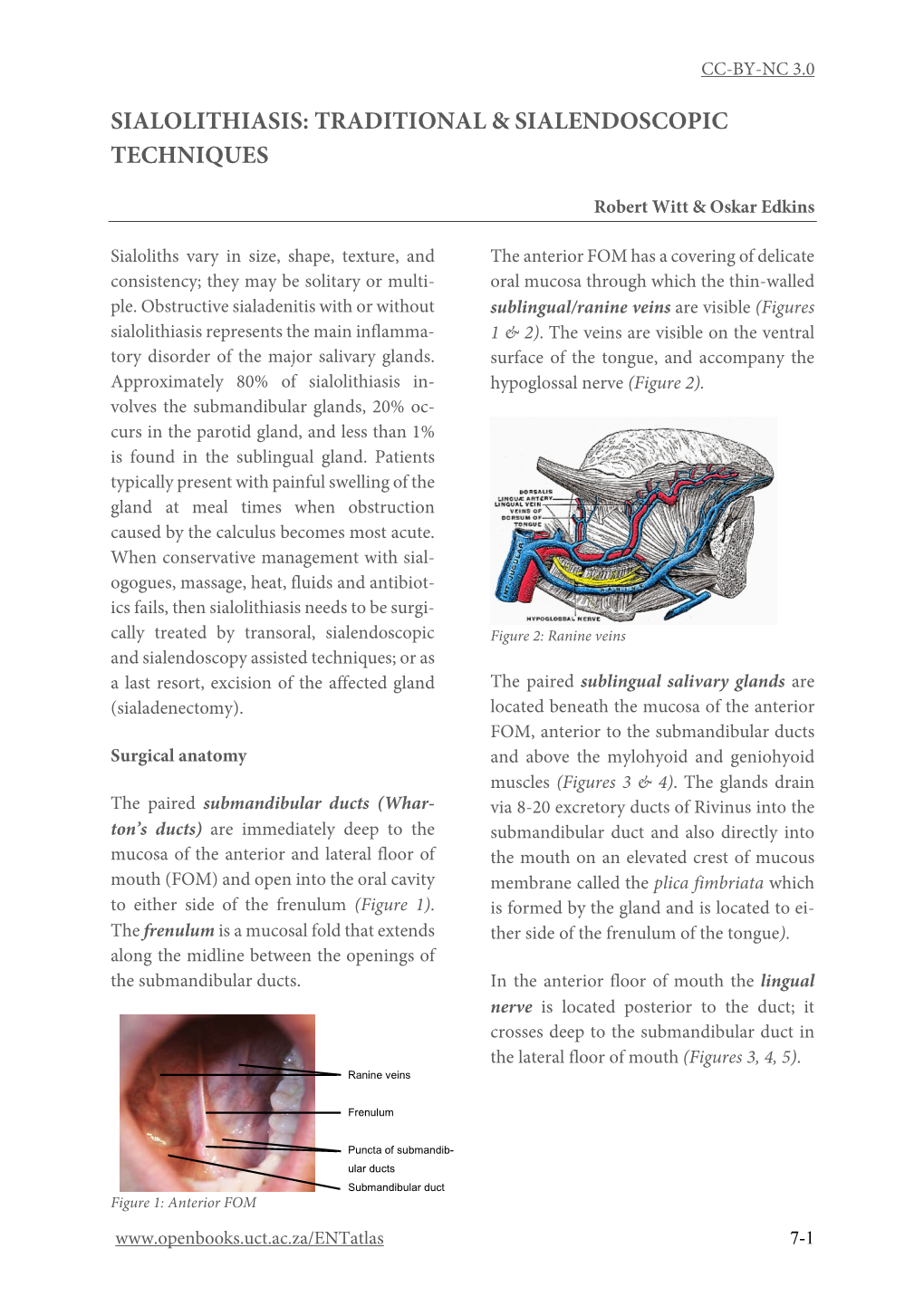

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parotid and Mandibular Salivary Glands Segmentation of the One Humped Dromedary Camel (Camelus Dromedarius)

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2017). 4(11): 32-41 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG(USA) Volume 4, Issue 11 - 2017 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2017.04.11.005 Parotid and Mandibular Salivary Glands Segmentation Of The One Humped Dromedary Camel (Camelus dromedarius) Hamdy M. Rezk and Nora A. Shaker* Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The present study provides detailed anatomical description of the parotid and mandibular salivary glands of the one humped camel with their segmentation based on arterial blood supply and salivary ducts; to facilitate partial removal of the pathologic gland. The shape, position, relations and blood supply of both salivary glands with their ducts were studied on six cadaveric heads. The mandibular and parotid ducts were injected with Urographin® as contrast medium; through inserting the catheter into their openings in the oral cavity; then applying lateral radiography immediately after the injection. The common carotid arteries were injected with red Latex Neoprene and dissected. The parotid gland was irregular rectangular and had five processes while the mandibular gland was irregular triangular with rounded proximal and pointed distal extremity. The parotid duct enters the oral cavity on the cheek opposite the upper 4th molar tooth. The mandibular duct opens in the oral cavity at the sublingual caruncles on the sublingual floor, just about 2cm cranial to frenulum linguae. Both The parotid and the mandibular salivary glands could be divided into four segments. -

Sjogren's Syndrome an Update on Disease Pathogenesis, Clinical

Clinical Immunology 203 (2019) 81–121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Immunology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yclim Review Article Sjogren’s syndrome: An update on disease pathogenesis, clinical T manifestations and treatment ⁎ Frederick B. Vivinoa, , Vatinee Y. Bunyab, Giacomina Massaro-Giordanob, Chadwick R. Johra, Stephanie L. Giattinoa, Annemarie Schorpiona, Brian Shaferb, Ammon Peckc, Kathy Sivilsd, ⁎ Astrid Rasmussend, John A. Chiorinie, Jing Hef, Julian L. Ambrus Jrg, a Penn Sjögren's Center, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 3737 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA b Scheie Eye Institute, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, 51 N. 39th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, PO Box 100125, Gainesville, FL 32610, USA d Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Arthritis and Clinical Immunology Program, 825 NE 13th Street, OK 73104, USA e NIH, Adeno-Associated Virus Biology Section, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Building 10, Room 1n113, 10 Center DR Msc 1190, Bethesda, MD 20892-1190, USA f Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Peking University People’s Hospital, Beijing 100044, China g Division of Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology, SUNY at Buffalo School of Medicine, 100 High Street, Buffalo, NY 14203, USA 1. Introduction/History and lacrimal glands [4,11]. The syndrome is named, however, after an Ophthalmologist from Jonkoping, Sweden, Dr Henrik Sjogren, who in Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) is one of the most common autoimmune 1930 noted a patient with low secretions from the salivary and lacrimal diseases. It may exist as either a primary syndrome or as a secondary glands. -

Variations of Parotidectomy – Indications and Technique

Variations of Parotidectomy – Indications and Technique Kerry D. Olsen, M.D. Professor and Chair Head and Neck Surgery Mayo Clinic Parotidectomy Personal experience > 32 years • 60 – 100 cases per year • Variety of neoplasms and anatomic variations • Minimal morbidity overall • Recurrent neoplasms – challenging cases 1 Parotid Surgery - Challenges Patient expectations Variety of tumors encountered Relationship and size of the tumor to the nerve Extend the operation as needed Role of pathology Parotidectomy Surgical options: • Superficial parotidectomy • Partial parotidectomy • Deep lobe parotidectomy • Total parotidectomy • Extended parotidectomy 4 2 Surgical Technique Superficial parotidectomy Deep lobe parotidectomy Surgeons will spend their entire career trying to learn when it is safe or necessary to do more or less than a superficial parotidectomy 5 Superficial Parotidectomy Indications • Neoplasm • Risk of metastasis • Recurrent infection/abscess • Surgical exposure – deep lobe/ parapharynx/ infratemporal fossa • Cosmesis 6 3 Pre-operative Discussion Individualized • Goals – rational – risks Goals – safe and complete removal with surrounding margin of normal tissue and preservation of facial nerve function 7 8 4 9 10 5 11 12 6 13 14 7 Facial Nerve Identification Helpful: • Cartilaginous pointer • Posterior belly of the digastric muscle • Mastoid tip Retrograde dissection Mastoid dissection 15 16 8 17 18 9 19 20 10 Superficial Parotidectomy Surgical goals • Avoid facial nerve injury • Remove tumor with surrounding -

Salivary Gland Infections and Salivary Stones (Sialadentis and Sialithiasis)

Salivary Gland Infections and Salivary Stones (Sialadentis and Sialithiasis) What is Sialadenitis and Sialithiasis? Sialdenitis is an infection of the salivary glands that causes painful swelling of the glands that produce saliva, or spit. Bacterial infections, diabetes, tumors or stones in the salivary glands, and tooth problems (poor oral hygiene) may cause a salivary gland infection. The symptoms include pain, swelling, pus in the mouth, neck skin infection. These infections and affect the submandibular gland (below the jaw) or the parotid glands (in front of the ears). The symptoms can be minor and just be a small swelling after meals (symptoms tend to be worse after times of high saliva flow). Rarely, the swelling in the mouth will progress and can cut off your airway and cause you to stop breathing. What Causes Sialadenitis and Sialithiasis When the flow of saliva is blocked by a small stone (salilithiasis) in a salivary gland or when a person is dehydrated, bacteria can build up and cause an infection. A viral infection, such as the mumps, also can cause a salivary gland to get infected and swell. These infections can also be caused by a spread from rotten or decaying teeth. Sometimes there can be a buildup of calcium in the saliva ducts that form into stones. These can easily stop the flow of saliva and cause problems How are these infections and stones treated? Treatment depends on what caused your salivary gland infection. If the infection is caused by bacteria, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics. Home treatment such as drinking fluids, applying warm compresses, and sucking on lemon wedges or sour candy to increase saliva may help to clear the infection quicker. -

Abscesses Apicectomy

BChD, Dip Odont. (Mondchir.) MBChB, MChD (Chir. Max.-Fac.-Med.) Univ. of Pretoria Co Reg: 2012/043819/21 Practice.no: 062 000 012 3323 ABSCESSES WHAT IS A TOOTH ABSCESS? A dental/tooth abscess is a localised acute infection at the base of a tooth, which requires immediate attention from your dentist. They are usually associated with acute pain, swelling and sometimes an unpleasant smell or taste in the mouth. More severe infections cause facial swelling as the bacteria spread to the nearby tissues of the face. This is a very serious condition. Once the swelling begins, it can spread rapidly. The pain is often made worse by drinking hot or cold fluids or biting on hard foods and may spread from the tooth to the ear or jaw on the same side. WHAT CAUSES AN ABSCESS? Damage to the tooth, an untreated cavity, or a gum disease can cause an abscessed tooth. If the cavity isn’t treated, the inside of the tooth can become infected. The bacteria can spread from the tooth to the tissue around and beneath it, creating an abscess. Gum disease causes the gums to pull away from the teeth, leaving pockets. If food builds up in one of these pockets, bacteria can grow, and an abscess may form. An abscess can cause the bone around the tooth to dissolve. WHY CAN'T ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT ALONE BE USED? Antibiotics will usually help the pain and swelling associated with acute dental infections. However, they are not very good at reaching into abscesses and killing all the bacteria that are present. -

Outpatient Versus Inpatient Superficial Parotidectomy: Clinical and Pathological Characteristics Daniel J

Lee et al. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (2021) 50:10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00484-9 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Outpatient versus inpatient superficial parotidectomy: clinical and pathological characteristics Daniel J. Lee1†, David Forner1,2†, Christopher End3, Christopher M. K. L. Yao1, Shireen Samargandy1, Eric Monteiro1,4, Ian J. Witterick1,4 and Jeremy L. Freeman1,4* Abstract Background: Superficial parotidectomy has a potential to be performed as an outpatient procedure. The objective of the study is to evaluate the safety and selection profile of outpatient superficial parotidectomy compared to inpatient parotidectomy. Methods: A retrospective review of individuals who underwent superficial parotidectomy between 2006 and 2016 at a tertiary care center was conducted. Primary outcomes included surgical complications, including transient/ permanent facial nerve palsy, wound infection, hematoma, seroma, and fistula formation, as well as medical complications in the postoperative period. Secondary outcome measures included unplanned emergency room visits and readmissions within 30 days of operation due to postoperative complications. Results: There were 238 patients included (124 in outpatient and 114 in inpatient group). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of gender, co-morbidities, tumor pathology or tumor size. There was a trend towards longer distance to the hospital from home address (111 Km in inpatient vs. 27 in outpatient, mean difference 83 km [95% CI,- 1 to 162 km], p = 0.053). The overall complication rates were comparable between the groups (24.2% in outpatient group vs. 21.1% in inpatient, p = 0.56). There was no difference in the rate of return to the emergency department (3.5% vs 5.6%, p = 0.433) or readmission within 30 days (0.9% vs 0.8%, p = 0.952). -

Oral Manifestations of Systemic Disease Their Clinical Practice

ARTICLE Oral manifestations of systemic disease ©corbac40/iStock/Getty Plus Images S. R. Porter,1 V. Mercadente2 and S. Fedele3 provide a succinct review of oral mucosal and salivary gland disorders that may arise as a consequence of systemic disease. While the majority of disorders of the mouth are centred upon the focus of therapy; and/or 3) the dominant cause of a lessening of the direct action of plaque, the oral tissues can be subject to change affected person’s quality of life. The oral features that an oral healthcare or damage as a consequence of disease that predominantly affects provider may witness will often be dependent upon the nature of other body systems. Such oral manifestations of systemic disease their clinical practice. For example, specialists of paediatric dentistry can be highly variable in both frequency and presentation. As and orthodontics are likely to encounter the oral features of patients lifespan increases and medical care becomes ever more complex with congenital disease while those specialties allied to disease of and effective it is likely that the numbers of individuals with adulthood may see manifestations of infectious, immunologically- oral manifestations of systemic disease will continue to rise. mediated or malignant disease. The present article aims to provide This article provides a succinct review of oral manifestations a succinct review of the oral manifestations of systemic disease of of systemic disease. It focuses upon oral mucosal and salivary patients likely to attend oral medicine services. The review will focus gland disorders that may arise as a consequence of systemic upon disorders affecting the oral mucosa and salivary glands – as disease. -

Surgical Treatment of Chronic Parotitis

Published online: 2018-10-24 THIEME Original Research 83 Surgical Treatment of Chronic Parotitis Rik Johannes Leonardus van der Lans1 Peter J.F.M. Lohuis1 Joost M.H.H. van Gorp2 Jasper J. Quak1 1 Department of ENT & Head and Neck Surgery, Diakonessenhuis, Address for correspondence Rik Johannes Leonardus van der Lans, Utrecht, Netherlands MD, Department of ENT- & Head and Neck Surgery, Diakonessenhuis, 2 Department of Pathology, Diakonessenhuis, Utrecht, Netherlands location Utrecht, Bosboomstraat 1, 3582 KE, Utrecht, Netherlands (e-mail: [email protected]). Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2019;23:83–87. Abstract Introduction chronic parotitis (CP) is a hindering, recurring inflammatory ailment that eventually leads to the destruction of the parotid gland. When conservative measures and sialendoscopy fail, parotidectomy can be indicated. Objective to evaluate the efficacy and safety of parotidectomy as a treatment for CP unresponsive to conservative therapy, and to compare superficial and near-total parotidectomy (SP and NTP). Methods retrospective consecutive case series of patients who underwent paroti- dectomy for CP between January 1999 and May 2012. The primary outcome variables were recurrence, patient contentment, transient and permanent facial nerve palsy and Frey syndrome. The categorical variables were analyzed using the two-sided Fisher exact test. Alongside, an elaborate review of the current literature was conducted. Results a total of 46 parotidectomies were performed on 37 patients with CP. Near- total parotidectomy was performed in 41 and SP in 5 cases. Eighty-four percent of patients was available for the telephone questionnaire (31 patients, 40 parotidec- tomies) with a mean follow-up period of 6,2 years. Treatment was successful in 40/46 parotidectomies (87%) and 95% of the patients were content with the result. -

Head and Neck

DEFINITION OF ANATOMIC SITES WITHIN THE HEAD AND NECK adapted from the Summary Staging Guide 1977 published by the SEER Program, and the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Fifth Edition published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging. Note: Not all sites in the lip, oral cavity, pharynx and salivary glands are listed below. All sites to which a Summary Stage scheme applies are listed at the begining of the scheme. ORAL CAVITY AND ORAL PHARYNX (in ICD-O-3 sequence) The oral cavity extends from the skin-vermilion junction of the lips to the junction of the hard and soft palate above and to the line of circumvallate papillae below. The oral pharynx (oropharynx) is that portion of the continuity of the pharynx extending from the plane of the inferior surface of the soft palate to the plane of the superior surface of the hyoid bone (or floor of the vallecula) and includes the base of tongue, inferior surface of the soft palate and the uvula, the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, the glossotonsillar sulci, the pharyngeal tonsils, and the lateral and posterior walls. The oral cavity and oral pharynx are divided into the following specific areas: LIPS (C00._; vermilion surface, mucosal lip, labial mucosa) upper and lower, form the upper and lower anterior wall of the oral cavity. They consist of an exposed surface of modified epider- mis beginning at the junction of the vermilion border with the skin and including only the vermilion surface or that portion of the lip that comes into contact with the opposing lip. -

Basic Histology (23 Questions): Oral Histology (16 Questions

Board Question Breakdown (Anatomic Sciences section) The Anatomic Sciences portion of part I of the Dental Board exams consists of 100 test items. They are broken up into the following distribution: Gross Anatomy (50 questions): Head - 28 questions broken down in this fashion: - Oral cavity - 6 questions - Extraoral structures - 12 questions - Osteology - 6 questions - TMJ and muscles of mastication - 4 questions Neck - 5 questions Upper Limb - 3 questions Thoracic cavity - 5 questions Abdominopelvic cavity - 2 questions Neuroanatomy (CNS, ANS +) - 7 questions Basic Histology (23 questions): Ultrastructure (cell organelles) - 4 questions Basic tissues - 4 questions Bone, cartilage & joints - 3 questions Lymphatic & circulatory systems - 3 questions Endocrine system - 2 questions Respiratory system - 1 question Gastrointestinal system - 3 questions Genitouirinary systems - (reproductive & urinary) 2 questions Integument - 1 question Oral Histology (16 questions): Tooth & supporting structures - 9 questions Soft oral tissues (including dentin) - 5 questions Temporomandibular joint - 2 questions Developmental Biology (11 questions): Osteogenesis (bone formation) - 2 questions Tooth development, eruption & movement - 4 questions General embryology - 2 questions 2 National Board Part 1: Review questions for histology/oral histology (Answers follow at the end) 1. Normally most of the circulating white blood cells are a. basophilic leukocytes b. monocytes c. lymphocytes d. eosinophilic leukocytes e. neutrophilic leukocytes 2. Blood platelets are products of a. osteoclasts b. basophils c. red blood cells d. plasma cells e. megakaryocytes 3. Bacteria are frequently ingested by a. neutrophilic leukocytes b. basophilic leukocytes c. mast cells d. small lymphocytes e. fibrocytes 4. It is believed that worn out red cells are normally destroyed in the spleen by a. neutrophils b. -

Salivary Glands

GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM [Anatomy and functions of salivary gland] 1 INTRODUCTION Digestive system is made up of gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) or alimentary canal and accessory organs, which help in the process of digestion and absorption. GI tract is a tubular structure extending from the mouth up to anus, with a length of about 30 feet. GI tract is formed by two types of organs: • Primary digestive organs. • Accessory digestive organs 2 Primary Digestive Organs: Primary digestive organs are the organs where actual digestion takes place. Primary digestive organs are: Mouth Pharynx Esophagus Stomach 3 Anatomy and functions of mouth: FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF MOUTH: Mouth is otherwise known as oral cavity or buccal cavity. It is formed by cheeks, lips and palate. It encloses the teeth, tongue and salivary glands. Mouth opens anteriorly to the exterior through lips and posteriorly through fauces into the pharynx. Digestive juice present in the mouth is saliva, which is secreted by the salivary glands. 4 ANATOMY OF MOUTH 5 FUNCTIONS OF MOUTH: Primary function of mouth is eating and it has few other important functions also. Functions of mouth include: Ingestion of food materials. Chewing the food and mixing it with saliva. Appreciation of taste of the food. Transfer of food (bolus) to the esophagus by swallowing . Role in speech . Social functions such as smiling and other expressions. 6 SALIVARY GLANDS: The saliva is secreted by three pairs of major (larger) salivary glands and some minor (small) salivary glands. Major glands are: 1. Parotid glands 2. Submaxillary or submandibular glands 3. Sublingual glands. 7 Parotid Glands: Parotid glands are the largest of all salivary glands, situated at the side of the face just below and in front of the ear. -

Salivary Glands; the Parotid Submandibular and Sublingual Functions of Saliva

Lecture series Gastrointestinal tract Professor Shraddha Singh, Department of Physiology, KGMU, Lucknow Various secretions from GIT First secretion from GIT that encounter the food is SALIVARY SECRETIONS What is saliva • Saliva is the mixed glandular secretion which constantly bathes the teeth and the oral mucosa • First secretion encounter the food • It is vital for oral health • It is constituted by the secretions of the three paired major salivary glands; The Parotid Submandibular and Sublingual Functions of saliva 1. Defense: a. Antibacterial b. Antifungal c.Immunological 2. Digestive function: a. Digestive enzymes – ptyalin, lipase b. Formation of bolus c. Taste 3. Protective function: a. Protective coating for hard tissues-teeth b. Protective coating for soft tissues 4. Lubricative function: a.Keeps the oral cavity moist b.Facilitates speech c.Helps in mastication and swallowing 5. Buffering function Salivary glands Structure of Salivary Gland Parotid gland • Parotid is large accounts for 50% secretion of saliva • Situated in front of ear behind the ramus of mandible • Gland drain in to oral cavity opposite to second molar tooth • Secretions are basically serous Submandibular and Sub lingual gland • The submandibular gland is about half the size of the parotid gland • It lies above the mylohyoid in the floor of the mouth. It opens into the floor of the mouth underneath the anterior part of the tongue • The sublingual is the smallest of the paired major salivary glands, being about one fifth the size of the submandibular. • It