To View This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

Devotion and Polemic in Eighteenth-Century England: William Mason and the Literature of Lay Evangelical Anglicanism

Devotion and Polemic in Eighteenth-Century England: William Mason and the Literature of Lay Evangelical Anglicanism Simon Lewis abstract William Mason (1719–1791), an Anglican evangelical lay- man of Bermondsey, London, published extensively on theological issues to educate the Anglican laity in the Church of England’s Reformed tradi- tion. Despite the popularity of his writings, Mason has been neglected by scholars. By providing the first large-scale examination of Mason’s works, Simon Lewis shows that eighteenth-century Calvinist evangelicalism bene- fited from an active and vocal laity, whose evangelistic strategies were not limited to preaching; provides a model for how scholars can integrate piety and polemic in their explorations of religious print culture; and enhances our understanding of the laity’s engagement in theological controversies. Keywords: devotion; polemic; Anglicanism; Methodism; Calvinism Only relatively recently has scholarship of evangelicalism in eighteenth-century England benefited from fresh attention to the laity. In Heart Reli- gion in the British Enlightenment (2008), Phyllis Mack considers the ways in which female Methodist leaders—particularly Mary Bosanquet Fletcher—discerned spiri- tual authority and direction from their dreams.1 Antje Matthews similarly empha- sizes lay experience by exploring the evangelical painter John Russell, who recorded his feelings and anxieties.2 While these studies of lay spirituality have certainly enhanced our understanding of eighteenth-century evangelicalism, their empha- sis on religious experience has meant that the importance of polemic has often been neglected. The question of whether devotional piety took priority over religious 1. Phyllis Mack, Heart Religion in the British Enlightenment: Gender and Emotion in Early Methodism (Cambridge, 2008). -

NORFOLK. • Witton & Worstead

518 NORTH W ALSHAM, NORFOLK. • Witton & Worstead. Rapping division-Brunstead, Medical Officer & Public Vaccinator, North Walsham Catfield, East Ruston, Happisburgh, Hempstead-cum District, Smallburgh Union, Sidney Hope Harrison Eccles, Hiclding, Horsey, Ingham, Lessingham, Lud M.R.C.S.Eng., L.R.C.P.Lond. Aylsham road ham, Palling, Potter Heigham, Stalham, Sutton, Wal Medical Officer & Public Vaccinator, Southrepps District, cott & W a:xham Erpingham Union, John Shepheard B.A.,M.R.C.S.Eng., L.R.C.P.Lond. Cromer road 1 NORTH WALSHAM SUB-COMMITTEE OF NORFOLK Registrar of Marriages & Deputy for Births & Deaths LOCAL PENSION COMMITTEE. for the Smallburgh District, Ernest W. Gregory, ' The following places are included in the Sub-District: Excelsior house, -King's Arms street Alby, Aldborough, Antingham, Bacton, Banningham, Relieving & Vaccination Officer, Tunstead District & ,Barton Turf, Beeston St. Lawrence, Bradfield, Brum Registrar of Births & Deaths, North Walsham District;, stead, Burgh, Calthorpe, Catfield, Colby, Crostwight, "Smallburgh Union, George Boult Hewitt, Yarmouth rd Dilham, Ea~t Ruston, Edingthorpe, Erpingham, Fel Superintendent Registrar of Smallburgh Union, Fairfax mingham, Gimingham, Gunton, Happisburgh, Hemp Davies. Grammar School road stead-cum-Eccles, Hickling, Honing, Ingham, Ingworth, PLACES OF WORSHIP, with times of Services. Irstead, Knapton, Lessingham, Mundesley, Neatishead, _N orthrepps, North Walsham, Overstrand, Oxnead, St. Nicholas Church, Rev. Robert Aubrey Aitken M.A. Paston, Ridlington, Sidestrand, Skeyton, Sea Palling, vicar & rural dean; Rev. Tom Harry Cromwell Nash Smallburgh, Southrepps, Suffield, Sutton, Swafield, Th.A.K.C. curate; 8 & II a.m. & 3 & 6.30 p.m. ; Stalham, Swanton Abbott, Thorpe Market, Thwaite, mon. wed. & fri. li a.m. ; tues. thurs. -

Proposals to Spend £1.5M of Additional Funding from Norfolk County Council

App 1 Proposals to spend £1.5m of additional funding from Norfolk County Council District Area Road Number Parish Road Name Location Type of Work Estimated cost Breckland South B1111 Harling Various HGV Cell Review Feasibility £10,000 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road near recycle centre Resurfacing 8,164 Breckland West C768 Ashill Swaffham Road on bend o/s Church Resurfacing 14,333 Breckland West 33261 Hilborough Coldharbour Lane nearer Gooderstone end Patching 23,153 Breckland West C116 Holme Hale Station Road jnc with Hale Rd Resurfacing 13,125 Breckland West B1108 Little Cressingham Brandon Road from 30/60 to end of ind. Est. Resurfacing 24,990 Breckland West 30401 Thetford Kings Street section in front of Kings Houseresurface Resurface 21,000 Breckland West 30603 Thetford Mackenzie Road near close Drainage 5,775 £120,539 Broadland East C441 Blofield Woodbastwick Road Blofield Heath - Phase 2 extension Drainage £15,000 Broadland East C874 Woodbastwick Plumstead Road Through the Shearwater Bends Resurfacing £48,878 Broadland North C593 Aylsham Blickling Road Blickling Road Patching £10,000 Broadland North C494 Aylsham Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Buxton Rd / Aylsham Rd Patching £15,000 Broadland North 57120 Aylsham Hungate Street Hungate Street Drainage £10,000 Broadland North 57099 Brampton Oxnead Lane Oxnead Lane Patching £5,000 Broadland North C245 Buxton the street the street Patching £5,000 Broadland North 57120 Horsford Mill lane Mill lane Drainage £5,000 Broadland North 57508 Spixworth Park Road Park Road Drainage £5,000 Broadland -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of Parish

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Aldborough and Thurgarton Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Murat Anne M Tony Road, Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Elliott Ruth Paul Martin Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Elliott Paul M David Peter Green, Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Grieves John B Jean Elizabeth Aldborough, NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Freeman James H J Peter Thurgarton Road, Aldborough, NR11 7NY *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry is made in the last column have been and stand validly nominated. Dated: Friday 10 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED North Norfolk Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Antingham Reason why Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer no longer nominated* EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Long Trevor F Graham Fredrick Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach Independent Bacon Robert H Graham House, Antingham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. Walsham, NR28 0NJ LONG The Old Forge, Everson Graham F Trevor Francis Elderton Lane, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NR LOVE Holly Cottage, McLeod Lynn W Steven Paul Antingham Hill, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0NH PARAMOR Field View, Long Trevor F Stuart John Southrepps Road, Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. -

North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents

LCA cover 09:Layout 1 14/7/09 15:31 Page 1 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT NORTH NORFOLK Local Development Framework Landscape Character Assessment Supplementary Planning Document www.northnorfolk.org June 2009 North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team Telephone: 01263 516318 E-Mail: [email protected] Write to: Planning Policy Manager, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.northnorfolk.org/ldf All of the LDF Documents can be made available in Braille, audio, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516318 to discuss your requirements. Cover Photo: Skelding Hill, Sheringham. Image courtesy of Alan Howard Professional Photography © North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment Contents 1 Landscape Character Assessment 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 What is Landscape Character Assessment? 5 2 North Norfolk Landscape Character Assessment 9 2.1 Methodology 9 2.2 Outputs from the Characterisation Stage 12 2.3 Outputs from the Making Judgements Stage 14 3 How to use the Landscape Character Assessment 19 3.1 User Guide 19 3.2 Landscape Character Assessment Map 21 Landscape Character Types 4 Rolling Open Farmland 23 4.1 Egmere, Barsham, Tatterford Area (ROF1) 33 4.2 Wells-next-the-Sea Area (ROF2) 34 4.3 Fakenham Area (ROF3) 35 4.4 Raynham Area (ROF4) 36 4.5 Sculthorpe Airfield Area (ROF5) 36 5 Tributary Farmland 39 5.1 Morston and Hindringham (TF1) 49 5.2 Snoring, Stibbard and Hindolveston (TF2) 50 5.3 Hempstead, Bodham, Aylmerton and Wickmere Area (TF3) 51 5.4 Roughton, Southrepps, Trunch -

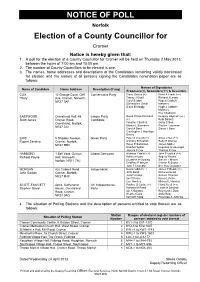

Notice of Poll

NOTICE OF POLL Norfolk Election of a County Councillor for Cromer Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Cromer will be held on Thursday 2 May 2013, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors COX 12 Grange Court, Cliff Conservative Party Claire Davies (+) Peter A Frank (++) Hilary Ave, Cromer, Norwich, Tracey J Khalil Richard J Leeds NR27 0AF Carol Selwyn Rupert Cabbell- Gwendoline Smith Manners Diana B Meggy Hugh J Cabbell- Manners Roy Chadwick EASTWOOD Overstrand Hall, 48 Labour Party David Phillip-Pritchard Gregory Hayman (++) Scott James Cromer Road, Candidate (+) Ruth Bartlett Overstrand, Norfolk, Timothy J Bartlett Garry S Bone NR27 0JJ Marion L Saunders Pauline Tuynman Carol A Bone Simon J Bone Christopher J Hamilton- Emery ERIS 5 Shipden Avenue, Green Party Peter A Crouch (+) Alicia J Hull (++) Rupert Sandino Cromer, Norfolk, Anthony R Bushell Ruby B Warner NR27 9BD Helen E Swanston James Spiller Heather Spiller Huguette A Gazengel Jessica F Cox Thomas P Cox HARBORD 1 Bell Yard, Gunton Liberal Democrat Andreas Yiasimi (+) John Frosdick (++) Richard Payne Hall, Hanworth, Kathleen Lane Angela Yiasimi Norfolk, NR11 7HJ Elizabeth A Golding -

CONTENTS E V Theme: with Heart and Mind a N G

ERT cover 30-3 8/6/06 10:37 Page 1 CONTENTS E V Theme: With Heart and Mind A N G Editorial – With Heart and Mind E L I page 195 C A Universalism and Evangelical Theology L R DAVID HILBORN AND DON HORROCKS E V I page 196 E W Biotheology: Theology, Ethics and the New O Biotechnologies F T BRIAN EDGAR H E page 219 O L Glossolalia in Korean Christianity: An Historical Survey O G BONJOUR BAY Y page 237 V O Articles and book reviews reflecting L Contextualization and Discipleship U M global evangelical theology for the purpose MINHO SONG E page 249 3 of discerning the obedience of faith 0 , Farewell Gerasenes: A Bible Study on Mark 5:1-20 N JOHN LEWIS O 3 page 264 , J u l Book Reviews y 2 page 271 0 0 6 Volume 30 No. 3 July 2006 Evangelical Review of Theology EDITOR: DAVID PARKER Volume 30 • Number 3 • July 2006 Articles and book reviews reflecting global evangelical theology for the purpose of discerning the obedience of faith Published by for WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission ISSN: 0144-8153 Volume 30 No. 3 July 2006 Copyright © 2006 World Evangelical Alliance Theological Commission Editor David Parker Committee The Executive Committee of the WEA Theological Commission Dr Rolf Hille, Executive Chair Editorial Policy The articles in the Evangelical Review of Theology reflect the opinions of the authors and reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of the Editor or the Publisher. Manuscripts, reports and communications should be addressed to the Editor and sent to Dr David Parker, 17 Disraeli St, Indooroopilly, 4068, Qld, Australia The Editors welcome recommendations of original or published articles or book reviews that relate to forthcoming issues for inclusion in the Review. -

1373478 N Norfolk DC X66 16:10 Mon, 25 Jan 2021

Date: 22 January Op: LES Workflow Revise: 25.1.21 2: KA H Size: 100 x 66 DAM AH: Lauren Pub: Eastern Daily Press P PLEASE CHECK SIZE IS CORRECT 1373478 N Norfolk DC x66 16:10 Mon, 25 Jan 2021 NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT PROCEDURE) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2015 NOTICE UNDER ARTICLE 15 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDING AND CONSERVATION AREAS) ACT 1990 I HEREBY GIVE NOTICE that North Norfolk District Council is dealing with the following applications: BLAKENEY PF/21/0023 Single storey extension to south elevation of dwelling; The Coast House, Back Lane, Blakeney, Holt, Norfolk, NR25 7NR for Mr Miles Morland; Reasons: c) BODHAM PP/21/0155 Permission in principle for erection of one self-build dwelling; Land North Of Hurricane Farm Bungalow, Church Road, Lower Bodham, Norfolk for Mr David Gay; Reasons: b) CROMER PF/20/2667 External insulation to rear of building; Flat 3, 7 Cadogan Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9HT for Mr Douglas Reid; Reasons: c) FIELD DALLING PF/21/0027 Installation of bi-fold doors to south elevation; new windows to east elevation and other external alterations; 14 School Road, Saxlingham, Holt, Norfolk, NR25 7LA for Anna Purser; Reasons: c) HOLT LA/20/2665 Works to install blue plaques on the elevations of Old School House; Old School House, Church Street, Holt, Norfolk, NR25 6BB for Gresham’s School; Reasons: e) HOLT PF/20/2674 Two single storey detached dwellings; The Castle, 1 The Grove, Cromer Road, Holt, Norfolk, NR25 6EB for Mr Storey; Reasons: b) f) MELTON CONSTABLE PF/20/2606 Two -

JOHN WESLEY (From a Painting Recently Presented to the /Iiission House), PROCEEDINGS

JOHN WESLEY (From a Painting recently presented to the /IIission House), PROCEEDINGS. A PORTRAIT OF JOHN WESLEY. REcENTLY PRESENTED TO THE MISSION HousE. The portrait of W esley reproduced in this issue of the Pro~dings has recently been presented to the Mission House by our Vice-President, Mr. E. S. Lamplough, (together with one of Dr. Coke). Mr. Lamplough kindly furnishes us with a photograph of the painting. The name of the artist is unknown. The portrait was originally owned by Mr. Lamplough's great-great-uncle, Mr. Richard Townend, who was born February 24, I 7s6, at Middleton, near Leeds. 1 He entered into partner ship in London with his brother-in-law, Mr. Richard Morris, who was an intimate friend of Wesley's. Mr. Towend also became acquainted with him, and joined the Foundery Society shortly before the City Road Chapel was erected, and continued in membership to the close of his long life of fourscore years. He died in 1837 at his house in the north corner of the City Road Chapel grounds, to which he had removed in 1803. His son, also Richard, married the daughter of Dr. James Hamilton, of City Road. Rev. Joseph Sutcliffe is reported to have said that the portrait was an excellent likeness of Wesley. We shall be pleased to receive from our readers any suggestions as to the name of the artist or other particulars. F. F. BRETHERTON. WESLEV'S TREE AT WINCHELSEA. (Continued from page 87). The ash tree, under which John Wesley preached his last out-door sermon, on October 7, 1790, was blown down during a heavy gale on Friday, September 23, 1927, at a few minutes before 6 o'clock in the evening.