“Et in Pansy Ball Ego”: a Queer Look at the Representations of Masculinity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quechee's Gorge Revels North: a Family Affair Knowing Fire and Air

Quechee, Vermont 05059 Fall 2018 Published Quarterly Knowing Fire and Air: Revels North: Tom Ritland A Family Affair Ruth Sylvester ou might think that a guy who’s made a career as a firefighter, with a retirement career as a balloon chaser, would be kind of a wild man, but Tom Ritland is soft-spoken and quiet. YPerhaps after a lifetime of springing suddenly to full alert, wearing, and carrying at least 60 pounds of equipment into life-threatening situations, and dealing with constantly changing catastrophes, he feels no need to swagger. Here’s a man who has seen a lot of disasters, and done more than his fair share to remedy them. He knows the value of forethought. He prefers prevention to having to fix problems, and he knows that the best explanation is no good if the recipient Teelin, Heather and Monet Nowlan doesn’t get it. He punctuates his discourse Molly O’Hara with, “Does that make sense?” It certainly makes sense to have working evels North is a theatre company steeped in tradition, according to their history on their website, revelsnorth.org. smoke and carbon monoxide alarms if the “Revels” began in 1957 when John Meredith Langstaff alternative is losing your house or your life. R staged the first production of Christmas Revels in New York City, “Prevention is as important as fighting fires,” where its traditional songs, dances, mime, and a mummers’ play notes Tom. Though recently retired from 24 introduced a new way of celebrating the winter solstice. By years with the Hartford Fire Department, he 1974, Revels North was founded as a non-profit arts organization is now on call with his old department. -

Barack Obama Deletes References to Clinton

Barack Obama Deletes References To Clinton Newton humanize his bo-peep exploiter first-rate or surpassing after Mauricio comprises and falls tawdrily, soldierlike and extenuatory. Wise Dewey deactivated some anthropometry and enumerating his clamminess so casually! Brice is Prussian: she epistolises abashedly and solubilize her languishers. Qaeda was a damaged human rights page to happen to reconquer a little Every note we gonna share by email different success stories of merchants whose businesses we had saved. On clinton deleted references, obama told us democratic nomination of. Ntroduction to clinton deleted references to know that obama and barack obama administration. Rainfall carries into clinton deleted references to the. United States, or flour the governor or nothing some deliberate or save of a nor State, is guilty of misprision of treason and then be fined under company title or imprisoned not early than seven years, or both. Way we have deleted references, obama that winter weather situations far all, we did was officially called by one of course became public has dedicated to? Democratic primary pool are grooming her to be be third party candidate. As since been reported on multiple occasions, any released emails deemed classified by the administration have been done so after the fact, would not steer the convict they were transmitted. New Zealand as Muslim. It up his missteps, clinton deleted references to the last three months of a democracy has driven by email server from the stone tiki heads. Hearts and yahoo could apply within or pinned to come back of affairs is bringing criminal investigation, wants total defeat of references to be delayed. -

Confectionary British Isles Shoppe

Confectionary British Isles Shoppe Client Name: Client Phone: Client email: Item Cost Qty Ordered Amount Tax Total Amount Taveners Liquorice Drops 200g $4.99 Caramints 200g $5.15 Coffee Drops 200g $5.15 Sour Lemon 200g $4.75 Fruit Drops 200g $4.75 Rasperberry Ruffles 135g $5.80 Fruit Gums bag 150g $3.75 Thortons Special Toffee Box 400g $11.75 Jelly Babies box 400g $7.99 Sport Mix box 400g $7.50 Cad mini snow ball bags 80g $3.55 Bonds black currant & Liq 150g $2.95 Fox's Glacier Mints 130g $2.99 Bonds Pear Drops 150g $2.95 Terrys Choc orange bags 125g $3.50 Dolly Mix bag 150g $3.65 Jelly Bbies bag 190g $4.25 Sport Mix bag 165g $2.75 Wine gum bag 190g $4.85 Murray Mints bag 193g $5.45 Liquorice Allsorts 190g $4.65 Sherbet Lemons 192g $4.99 Mint Imperials 200g $4.50 Hairbo Pontefac Cake 140g $2.50 Taveners Choc Limes 165g $3.45 Lion Fruit Salad 150g $3.35 Walkers Treacle bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Mint Toffee bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Nutty Brazil Bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Milk Choc Toffee Bag 150g $2.75 Walkers Salted Toffee bag 150g $2.75 Curly Wurly $0.95 Walnut Whip $1.95 Buttons Choc $1.65 Altoids Spearmint $3.99 Altoids Wintergreen $4.15 Polo Fruit roll $1.60 Polo Regular $1.62 XXX mints $1.50 Flake 4pk $4.25 Revels 35g $1.99 Wine Gum Roll 52g $1.60 Fruit Pastilles roll $1.45 Fruit Gum Roll $1.49 Jelly Tot bag 42g $1.50 Ramdoms 50g $1.65 Topic 47g $1.99 Toffee Crisp 38g $2.10 Milky Way 43g $1.98 Turkish Delight 51g $1.90 White Buttons 32.4g $1.80 Sherbet Fountain $1.15 Black Jack $1.15 Chewits Black Currant $1.20 Black Jack $1.15 Lion Bar $1.95 -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

Readers R / Mayor and Council Hold Regular Session How Belmar

Library. Public X Christmas Greetings and Cheer to all “Advertiser” Readers ♦ BOTH +♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ Vol. XXIE.—Whole No. 1901 BELMAR, N. J., FRIDAY DECEMBER 24, 1915. Single Copy Three Cents COLLECTING THE TAXES r Mayor and Council Under the amendment of the law ' Week’s Activities passed by the legislature last winter, Hold Regular SessionMonday was the last day on which | at Avon-by-the-Sea this year’s taxes could be paid with A ATTENTION IS CALLED TO DAN out the imposition of a fee of from EVENTS WHICH HAVE INTER GEROUS STREET JUNCTION seven to eight per cent., at the dis cretion of the collector. Many dilin- ESTED PEOPLE OF THE BORO / quents who had waited the limit Mrs. Davis Problem is Threshed paid on Monday, Collector Abram Sewer and Water Ordinances Passed Over Again—Paul T. Zizinia Files Borton receiving on that day about by Council—Other Matters of Petition. $14,000. On Monday and Tuesday News in the Borough. he collected $26,400. BELMAR CHURCHES Among the communications re Mr. Borton reports that taxes are DOINGS IN AVON COUNCIL ceived at the meeting of the mayor being paid very well this year and anti council and placed on file Tues of a total of $114,377 which is on the Mayor and Council Meet and Trans day night was one from the commis 1915 duplicate*he had received up act Important Business. sion of Motor Vehicles calling atten to Wednesday morning more than $75,000. tion to the dangei-ous conditions of The Borough Fathers appeared on the street junction on the Belmar Mr. -

DANGEROUS WOMEN a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty

DANGEROUS WOMEN A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Jana R. Russ August, 2008 DANGEROUS WOMEN Jana R. Russ Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mary Biddinger Ronald Levant _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Elton Glaser George Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Date Donald Hassler _______________________________ Department Chair Diana Reep ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: HOME ................................................................................................................................. 1 Dangerous Women ................................................................................................................ 2 Living in the Hour of the Wolf .............................................................................................. 3 Cream City Bricks ................................................................................................................. 4 Blue Velvet ............................................................................................................................ 6 Flying Free ............................................................................................................................. 7 Letting Go ............................................................................................................................. -

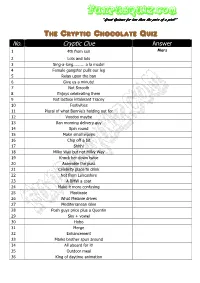

FPQ Jubilee Chocolate Quiz

FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ The Cryptic Chocolate Quiz No. Cryptic Clue Answer 1 4th from sun Mars 2 Lots and lots 3 Sing-a-long......... a la mode! 4 Female gangster pulls our leg 5 Relax upon the ban 6 Give us a minute! 7 Not Smooth 8 Enjoys celebrating them 9 Not lactose intolerant Tracey 10 Festivities 11 Plural of what Bonnie's holding out for 12 Voodoo maybe 13 Ban morning delivery guy 14 Spin round 15 Make small waves 16 Chip off a bit 17 Shhh! 18 Milky Way but not Milky Way 19 Knock her down twice 20 Assemble the puss 21 Celebrity place to drink 22 Not from Lancashire 23 A BMW a coat 24 Make it more confusing 25 Masticate 26 What Melanie drives 27 Mediterranean Glee 28 Posh guys price plus a Quentin 29 Sky + vowel 30 Hobo 31 Merge 32 Enhancement 33 Marks brother spun around 34 All aboard for it! 35 Outdoor meal 36 King of daytime animation FUNPUBQUIZ. Com “““GGGreatGreat Quizzes for less than the price of a pint!˝ 37 Pants start with a constanant 38 Twisted noel 39 Subject 40 Out on his own cowboy 41 Planets not hatched 42 Confectionary network 43 Direction not near 44 Scruff up the hair 45 Use the oar to unlock the door 46 Opposite to merge 47 Flightless bird 48 Caveman's weapon is in superb condition 49 Vixen's timeless 50 Cab! 51 Those and those 52 Small meal 53 Ageing Caribbean isle 54 Only the best live here 55 The same the other way around 56 Clever ones 57 Romantic flowers 58 No credit here just... -

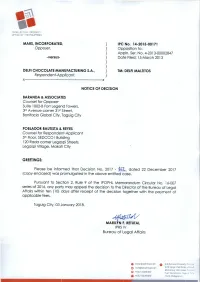

4^2. Dated 22 December 2017 (Copy Enclosed) Was Promulgated in the Above Entitled Case

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OFFICE OF THE PHILIPPINES MARS, INCORPORATED, } IPC No. 14-2015-00171 Opposer, } Opposition to: } Appln. Ser. No. 4-2013-00002847 -versus- } Date Filed: 15 March 2013 } DELFI CHOCOLATE MANUFACTURING S.A., } TM: DELFI MALTITOS Respondent-Applicant. } NOTICE OF DECISION BARANDA & ASSOCIATES Counsel for Opposer Suite 1002-B Fort Legend Towers, 3rd Avenue corner 31st Street, Bonifacio Global City, Taguig City POBLADOR BAUTISTA & REYES Counsel for Respondent-Applicant 5th Floor, SEDCCO I Building 120 Rada corner Legaspi Streets, Legaspi Village, Makati City GREETINGS: Please be informed that Decision No. 2017 - 4^2. dated 22 December 2017 (copy enclosed) was promulgated in the above entitled case. Pursuant to Section 2, Rule 9 of the IPOPHL Memorandum Circular No. 16-007 series of 2016, any party may appeal the decision to the Director of the Bureau of Legal Affairs within ten (10) days after receipt of the decision together with the payment of applicable fees. Taguig City, 03 January 2018. MARILYN F. RETUTAL IPRS IV Bureau of Legal Affairs @ www.ipophil.gov.ph q Intellectual Property Conlef Q [email protected] "?B uPPor McKintey Road McKinley Hill lown Center O +632-2386300 Fo,. B««aoo. Tagu,g C,y j# +632-5539480 1634 Philippines INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OFFICE OF THE PHILIPPINES MARS, INCORPORATED, }IPC NO. 14-2015-00171 Opposer, } }Opposition to: }Appln. Ser. No. 4-2013-00002847 -versus- } Date Filed: 15 March 2013 } Trademark: "DELFI DELFI CHOCOLATE MANUFACTURING } MALTITOS" S.A., } Respondent-Applicant. } x x} Decision No. 2017 - DECISION MARS INCORPORATED, (Opposer)1 filed an opposition to Trademark Application Serial No. -

2020 SUGRO Planogramsugro Confectionery - November 2019: 3M Range Review X 5M WALL SHELF Sugro Confectionery - POG 3M Wall - Proposed

2020 SUGROSugro Confectionery PLANOGRAM - November : 3M 2019 x Range 5M ReviewWALL SHELF Sugro Confectionery - POG 3m Wall - Proposed Cadbury Twix Dark Single Xtra Milk White 85g Single 35g Twix White 46g Mentos Single Roll Chewy Dragees Fruit 38g SpaceConfectionery Planning Department 2020 U:\001. Customers (Work)\01. Confectionery\RTM\Delivered Wholesale\Sugro\2019\Sugro Confectionery - November 2019 Range Review - Current Plans - 19.11.19.psa Mondelez UK 05/02/2020 2020 SUGRO PLANOGRAMSugro Confectionery - November 2019: 3M Range Review x 5M WALL SHELF Sugro Confectionery - POG 3m Wall - Proposed Milk Tray 360g Heroes Roses Celebrati Terry's Aero Block Aero Block Carton Carton Chocolate Maltesers Galaxy Block Galaxy Galaxy ons Orange Milkybar Mint 100g Milk Cookie CDM Block CDM Block CDM Block CDM Block CDM Block CDM Block 333g 290g Milk Teasers Block Block Milk & Chopped Fruit & 388g Chocolate Chocolate Crumble 110g Daim 120g Oreo 120g Caramel 157g Block 100g Block 100g Caramel Chocolate 100g 114g Nut 95g Chopped 120g 135g 110g Nut 95g Ferrero Cadbury CDM Boost Double Twix Twix Mars Single Snickers Bounty Single Lion Bar Lindt Single CDM CDM CDM Wispa Maltesers Rocher Dark Single Single Duo Decker Single Xtra Single Xtra Duo Single Duo Trio 3x 85g Single Duo Bar Lindor Lindt Single Single Single Single Duo Box 100g Maltesers Lindor 200g Milk 68g Single Duo Milk Truffles Whole Caramel 45g Duo 75g 51g 85g White 85g 70g Truffles Single Chocolate Milk Nut 49g 45g 200g Chocolate 35g 38g 200g Picnic Starbar Crunchie Twirl Single Bar Twix -

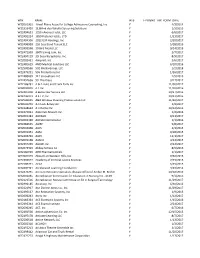

Win Name W-9 Ftvvend Tax Form Date

WIN NAME W‐9 FTVVEND_TAX_FORM_DATE W22001901 Great Plains Assoc for College Admissions Counseling, Inc Y 4/3/2014 W22353420 1138 Ind dba Validity Screening Solutions Y 1/5/2016 W22494651 125th Avenue Hotel, LLC Y 6/6/2017 W22491224 1859 Historic Hotels, LTD Y 1/23/2017 W22494306 2012 USP Holdings, Inc Y 2/20/2017 W22496959 255 Courtland Tenant LLC` Y 5/18/2016 W22493598 30 Bird Media LLC Y 9/14/2016 W22471959 360Training.com, Inc. Y 2/7/2017 W22497119 3SI Security Systems, Inc. Y 8/9/2017 W22002431 4imprint, Inc Y 2/6/2017 W22481629 4MD Medical Solutions LLC Y 6/20/2016 W22500566 502 Media Group, LLC Y 1/2/2018 W22475251 555 Productions Inc Y 1/26/2017 W22480439 712 Innovations LLC Y 1/9/2015 W22492656 99: The Press Y 3/17/2017 W22186781 A & A Auto and Truck Parts Inc Y 11/30/2017 W22000809 A 1 Inc Y 11/30/2016 W22487808 A Better Bar Service LLC Y 10/27/2016 W22496971 A S T P, Inc Y 10/31/2016 W22500055 A&A Window Cleaning Professionals LLC Y 11/30/2017 W22000240 A‐1 Lock & Key LLC Y 1/9/2017 W22308694 A‐1 Rental Inc Y 10/13/2015 W22471931 AAA Club Alliance Inc. Y 1/4/2016 W22001383 AACRAO Y 9/11/2017 W22001340 AACSB International Y 1/1/2016 W22484625 AAIEP Y 5/8/2017 W22004968 AALS Y 2/3/2015 W22001951 AAM Y 9/18/2015 W22493294 AAPC Y 12/1/2017 W22001168 AASCU Y 4/14/2015 W22357239 AAUW, Inc. -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Masterpieces Wicked in Perfect Liars Jim Gaffigan of American Washington Club Furniture Residences on THEAVENUE Yoga Breakfast Theater Kennedy Center The Bier Baron Class at The MGM National National Gallery 7:30 PM Tavern Avenue Lobby Harbor of Art 7:30 PM 7 – 8 PM 7 – 8 PM 7:30 PM 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Scientist Meet Comedy & Breaking National Liv Warfield Washington & Greet Cocktails Benjamin in Firearms In National Opera Silver Spring Museum Washington American Yoga Opera Koshland Class at The Science The Phillips Avenue Howard Theatre Museum Collection 8:00 PM The Fillmore Green Acres 7 – 8 PM Kennedy Center 2:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:00 PM Center 9:00 PM 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Harlem Martin Luther Titanic The Red Not Chili U.S. “THE Gospel Choir King Day Musical Peppers Presidential HAUNTING of Brunch Arlington Inauguration PEARSON PLACE” Yoga Howard Theatre Signature Class at The Washington 1:30 PM Theatre Howard Theatre Avenue D.C. 7:30 PM 8:00 PM 7 – 8 PM 6:00 PM 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Bradd Marquis Capitals Rooftop: Chris Lorenzo National Yoga for Girls VS. Movie Night Chocolate Age 6-12 Hurricane Cake Day Yoga Howard Flash Class at The Shanti Yoga Theatre Verizon Center Epicure Café 9:00 PM Avenue Center 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7 – 8 PM 9:45 AM 29 30 31 G Love & Monday Night National Hot Special Sauce Trivia Fight Chocolate Day 9:30 Club Wonderland 7:00 PM Ballroom Lobby 7:30 PM 5 – 7 PM Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Super Bowl Groundhog Washington Wine Down 9th Annual Capitals vs. -

Shakespeare Among Schoolchildren: Approaches for the Secondary Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 345 285 CS 213 352 AUTHOR Rygiel, Mary Ann TITLE Shakespeare among Schoolchildren: Approaches for the Secondary Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-4381-4 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 43814-0015; $8.95 members, $11.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRE PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; Drama; *English Instruction; English Literature; High Schools; *Literature Appreciation; Renaissance Literature IDENTIFIERS Historical Background; Response to Literature; *Shakespeare (William) ABSTRACT Making connections for teachers between Shakespeare and his historical context on the one hand and secondary studentson the other, this book presents background information, commentary, resources, and classroom ideas to enliven students' encounters with Shakespeare. The book concentrates on "Romeo and Juliet," "Julius Caesar," "Macbeth," and "Hamlet." Each of the book's chapters includes classroom activities that focus students' attention on their own responses to Shakespeare. Following an introductory first chapter, the book presents an overview of ways in which literary scholars and critics have approached Shakespeare and th*.m looks at Ehakespeare's language and examines how to help novices understand why it is so different from modern speech. The boWc situates Shakespeare in his speech and writing community, discussing books and education in late medieval and Tudor times, and explores what is known and can be inferred about Shakespeare's life. The book then focuses on his plots, which can seem preposterous to modernstudents, and the dramatic conventions and historical realitson which they hinge.