Changes in Diet in the Late Middle Ages: the Case of Harvest Workers*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeology of Early Medieval (6Th-12Th Century) Rural Settlements in France Édith Peytremann

The Archaeology of early medieval (6th-12th century) rural settlements in France Édith Peytremann To cite this version: Édith Peytremann. The Archaeology of early medieval (6th-12th century) rural settlements in France. Arqueología de la Arquitectura, Universidad del País Vasco ; Madrid : Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2012, Arqueología de la arquitectura y arquitectura deles- pacio doméstico en la alta Edad Media Europea (Quirós J.A., ed., Archaeology of Architecture and Household Archaeology in Early Medieval Europe), 9, pp.213-230. 10.3989/arqarqt.2012.11606. hal- 00942373 HAL Id: hal-00942373 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00942373 Submitted on 30 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arqueologia de la Arquitectura - 009_Arqueologia de la arquitectura 29/01/2013 10:39 Página 1 Arqueología de la Arqueología de la Arquitectura Arquitectura Volumen 9 enero-diciembre 2012 272 págs. ISSN: 1695-2731 Volumen 9 enero-diciembre 2012 Madrid / Vitoria (España) ISSN: 1695-2731 Sumario Teoría -

Territoriality and Beyond: Problematizing Modernity in International Relations Author(S): John Gerard Ruggie Source: International Organization, Vol

Territoriality and Beyond: Problematizing Modernity in International Relations Author(s): John Gerard Ruggie Source: International Organization, Vol. 47, No. 1 (Winter, 1993), pp. 139-174 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2706885 Accessed: 03-10-2017 17:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Organization This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Tue, 03 Oct 2017 17:56:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Territoriality and beyond: problematizing modernity in international relations John Gerard Ruggie We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. -T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding The year 1989 has already become a convenient historical marker: it has been invoked by commentators to indicate the end of the postwar era. An era is characterized by the passage not merely of time but also of the distinguishing attributes of a time, attributes that structure expectations and imbue daily events with meaning for the members of any given social collectivity. -

Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada

International Markets Bureau MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | JANUARY 2013 Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada Source: Shutterstock Consumer Trends Bakery Products in Canada MARKET SNAPSHOT INSIDE THIS ISSUE The bakery market in Canada, including frozen bakery and Market Snapshot 2 desserts, registered total value sales of C$8.6 billion and total volume sales of 1.2 million tonnes in 2011. The bakery Retail Sales 3 category was the second-largest segment in the total packaged food market in Canada, representing 17.6% of value sales in 2011. However, the proportional sales of this Market Share by Company 6 category, relative to other sub-categories, experienced a slight decline in each year over the 2006-2011 period. New Bakery Product 7 Launches The Canadian bakery market saw fair value growth from 2006 to 2011, but volume growth was rather stagnant. In New Bakery Product 10 addition, some sub-categories, such as sweet biscuits, Examples experienced negative volume growth during the 2006-2011 period. This stagnant volume growth is expected to continue over the 2011-2016 period. New Frozen Bakery and 12 Dessert Product Launches According to Euromonitor (2011), value growth during the 2011-2016 period will likely be generated from increasing New Frozen Bakery and 14 sales of high-value bakery products that offer nutritional Dessert Product Examples benefits. Unit prices are expected to be stable for this period, despite rising wheat prices. Sources 16 Innovation in the bakery market has become an important sales driver in recent years, particularly for packaged/ Annex: Definitions 16 industrial bread, due to the increasing demand for bakery products suitable for specific dietary needs, such as gluten-free (Euromonitor, 2011). -

Personal Relations, Political Agency, and Economic Clout in Medieval and Early Modern Royal and Elite Households

Introduction 1 Introduction Personal Relations, Political Agency, and Economic Clout in Medieval and Early Modern Royal and Elite Households Theresa Earenfight Studying a royal or elite household is a distinct form of scholarly voyeurism. We peep into the windows of people who died centuries ago and nose about in their closets and their pantries. Our gaze is scholarly and our intentions are good, but reading accounts of dinners both at home and on the road is not unlike reading the menu of a state dinner at the White House, or the catering accounts for a society wedding in London. It is a bit like reading a lifestyle magazine report on what people wore, who sat where at banquets, who rode at the head of a hunting party, and where people slept when they travelled. We see both women and men, from lowly chamber maids to lofty aristocratic men and women, engaged in the labor of keeping their lords and ladies dressed, fed, bathed, educated, protected, and entertained. The work recorded in household accounts was vital. A house is a physical structure – a building or place – but when historians talk about the household, they are talking about a group of people who lived and worked under the same roof and engaged in routine activities involved in caring for the well-being of family members.1 The household was the site of familiarity, friendship, nurtur- ing, intimacy, and sexual intimacy and, regardless of the social rank of the inhabitants, the household was deeply political. It was organized generally in ways that mirrored and reinforced patriarchal values with the husband and wife as the model for ruler and ruled. -

Alkaline Foods...Acidic Foods

...ALKALINE FOODS... ...ACIDIC FOODS... ALKALIZING ACIDIFYING VEGETABLES VEGETABLES Alfalfa Corn Barley Grass Lentils Beets Olives Beet Greens Winter Squash Broccoli Cabbage ACIDIFYING Carrot FRUITS Cauliflower Blueberries Celery Canned or Glazed Fruits Chard Greens Cranberries Chlorella Currants Collard Greens Plums** Cucumber Prunes** Dandelions Dulce ACIDIFYING Edible Flowers GRAINS, GRAIN PRODUCTS Eggplant Amaranth Fermented Veggies Barley Garlic Bran, wheat Green Beans Bran, oat Green Peas Corn Kale Cornstarch Kohlrabi Hemp Seed Flour Lettuce Kamut Mushrooms Oats (rolled) Mustard Greens Oatmeal Nightshade Veggies Quinoa Onions Rice (all) Parsnips (high glycemic) Rice Cakes Peas Rye Peppers Spelt Pumpkin Wheat Radishes Wheat Germ Rutabaga Noodles Sea Veggies Macaroni Spinach, green Spaghetti Spirulina Bread Sprouts Crackers, soda Sweet Potatoes Flour, white Tomatoes Flour, wheat Watercress Wheat Grass ACIDIFYING Wild Greens BEANS & LEGUMES Black Beans ALKALIZING Chick Peas ORIENTAL VEGETABLES Green Peas Maitake Kidney Beans Daikon Lentils Dandelion Root Pinto Beans Shitake Red Beans Kombu Soy Beans Reishi Soy Milk Nori White Beans Umeboshi Rice Milk Wakame Almond Milk ALKALIZING ACIDIFYING FRUITS DAIRY Apple Butter Apricot Cheese Avocado Cheese, Processed Banana (high glycemic) Ice Cream Berries Ice Milk Blackberries Cantaloupe ACIDIFYING Cherries, sour NUTS & BUTTERS Coconut, fresh Cashews Currants Legumes Dates, dried Peanuts Figs, dried Peanut Butter Grapes Pecans Grapefruit Tahini Honeydew Melon Walnuts Lemon Lime ACIDIFYING Muskmelons -

Fatty Liver Diet Guidelines

Fatty Liver Diet Guidelines What is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)? NAFLD is the buildup of fat in the liver in people who drink little or no alcohol. NAFLD can lead to NASH (Non- Alcoholic Steatohepatitis) where fat deposits can cause inflammation and damage to the liver. NASH can progress to cirrhosis (end-stage liver disease). Treatment for NAFLD • Weight loss o Weight loss is the most important change you can make to reduce fat in the liver o A 500 calorie deficit/day is recommended or a total weight loss of 7-10% of your body weight o A healthy rate of weight loss is 1-2 pounds/week • Change your eating habits o Avoid sugar and limit starchy foods (bread, pasta, rice, potatoes) o Reduce your intake of saturated and trans fats o Avoid high fructose corn syrup containing foods and beverages o Avoid alcohol o Increase your dietary fiber intake • Exercise more o Moderate aerobic exercise for at least 20-30 minutes/day (i.e. brisk walking or stationary bike) o Resistance or strength training at least 2-3 days/week Diet Basics: • Eat 3-4 times daily. Do not go more than 3-4 hours without eating. • Consume whole foods: meat, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, legumes, and whole grains. • Avoid sugar-sweetened beverages, added sugars, processed meats, refined grains, hydrogenated oils, and other highly processed foods. • Never eat carbohydrate foods alone. • Include a balance of healthy fat, protein, and carbohydrate each time you eat. © 7/2019 MNGI Digestive Health Healthy Eating for NAFLD A healthy meal includes a balance of protein, healthy fat, and complex carbohydrate every time you eat. -

Wic Approved Food Guide

MASSACHUSETTS WIC APPROVED FOOD GUIDE GOOD FOOD and A WHOLE LOT MORE! June 2021 Shopping with your WIC Card • Buy what you need. You do not have to buy all your foods at one time! • Have your card ready at check out. • Before scanning any of your foods, tell the cashier you are using a WIC Card. • When the cashier tells you, slide your WIC Card in the Point of Sale (POS) machine or hand your WIC Card to the cashier. • Enter your PIN and press the enter button on the keypad. • The cashier will scan your foods. • The amount of approved food items and dollar amount of fruits and vegetables you purchase will be deducted from your WIC account. • The cashier will give you a receipt which shows your remaining benefit balance and the date benefits expire. Save this receipt for future reference. • It’s important to swipe your WIC Card before any other forms of payment. Any remaining balance can be paid with either cash, EBT, SNAP, or other form of payment accepted by the store. Table of Contents Fruits and Vegetables 1-2 Whole Grains 3-7 Whole Wheat Pasta Bread Tortillas Brown Rice Oatmeal Dairy 8-12 Milk Cheese Tofu Yogurt Eggs Soymilk Peanut Butter and Beans 13-14 Peanut Butter Dried Beans, Lentils, and Peas Canned Beans Cereal 15-20 Hot Cereal Cold Cereal Juice 21-24 Bottled Juice - Shelf Stable Frozen Juice Infant Foods 25-27 Infant Fruits and Vegetables Infant Cereal Infant Formula For Fully Breastfeeding Moms and Babies Only (Infant Meats, Canned Fish) 1 Fruits and Vegetables Fruits and Vegetables Fresh WIC-Approved • Any size • Organic allowed • Whole, cut, bagged or packaged Do not buy • Added sugars, fats and oils • Salad kits or party trays • Salad bar items with added food items (dip, dressing, nuts, etc.) • Dried fruits or vegetables • Fruit baskets • Herbs or spices Any size Any brand • Any fruit or vegetable Shopping tip The availability of fresh produce varies by season. -

Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing

–8– “Bread from Heaven, Bread from the Earth”: Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus Over the last thirty years, Jewish studies scholars have turned increasing attention to food and meals in Jewish culture. These studies fall more or less into two different camps: (1) text-centered studies that focus on the authors’ idealized, often prescrip- tive construction of the meaning of food and Jewish meals, such as biblical and postbiblical dietary rules, the Passover Seder, or food in Jewish mysticism—“bread from heaven”—and (2) studies of the “performance” of Jewish meals, particularly in the modern period, which often focus on regional variations, acculturation, and assimilation—“bread from the earth.”1 This breakdown represents a more general methodological split that often divides Jewish studies departments into two camps, the text scholars and the sociologists. However, there is a growing effort to bridge that gap, particularly in the most recent studies of Jewish food and meals.2 The major insight of all of these studies is the persistent connection between eating and Jewish identity in all its various manifestations. Jews are what they eat. While recent Jewish food scholarship frequently draws on anthropological, so- ciological, and cultural historical studies of food,3 Jewish food scholars’ conver- sations with general food studies have been somewhat one-sided. Several factors account for this. First, a disproportionate number of Jewish food scholars (compared to other food historians) have backgrounds in the modern academic study of religion or rabbinical training, which affects the focus and agenda of Jewish food history. At the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, my background in religious studies makes me an anomaly. -

Medieval Cuisine

MEDIEVAL CUISINE Food as a Cultural Identity CHRISTOPHER MACMAHON CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY CHANNEL ISLANDS When reflecting upon the Middle Ages, there are many views that might come to one’s mind. One may think of Christian writings or holy warriors on crusade. Perhaps another might envision knights bedecked in heavy armor seeking honorable combat or perhaps an image of cities devastated by plague. Yet few would think of the Middle Ages in terms of cuisine. Cuisine in this time period can be approached in a variety of ways, but for many, the mere mention of food would provoke images of opulent feasts, of foods of luxury. David Waines takes this approach when looking at how medieval Islamic societies approached the idea of luxury foods. Waines begins with the idea invoked above, that a luxury food was one which was “expensive, pleasurable and unnecessary.”1 But, Waines goes on to ask, could not luxury also be considered a dish, no matter how humble the origin, whose preparation was so exquisite that it was beyond compare?2 While challenging the traditional thinking in regards to how one views cuisine, it must be noted that Waines’ focus is upon luxury foods. Whether prohibitively expensive or expertly prepared, such dishes would only be available to a very select elite. Another common method for looking at the role food played in medieval life is to look at the relationship between food and the economy. This relationship occurred in both local and international trade. Derek Keene investigates how cities “profoundly influenced the economies… of their hinterlands” by examining the relationship between the city of London and the area surrounding the city.3 Keene demonstrates that a network of ringed zones worked outward from the city, each with a specific support function. -

Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe

Published on Swaggerty's Farm (https://www.swaggertys.com) Home > Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe This breakfast sandwich recipe is so delicious & easy you may wonder why you never thought of it. Eggs & hash brown potatoes, covered with melted cheese & topped with slices of hot sausage, sandwiched between hot toasted, straight from the oven cinnamon bread. Drizzle with maple syrup! Bam! PDF [1] PRINT [1] SHARE Cinnamon Bread Breakfast Sandwich Recipe Directions 1. Preheat oven to 375 degrees. 2. Smear slices of Cinnamon Swirl bread on both sides with softened butter. Lay slices out flat on a baking sheet. Set aside. 3. Whisk together the eggs and a pinch of salt & black pepper. 4. Stir the shredded potatoes into the eggs. 5. Scoop egg-potato mixture into a hot skillet with melted butter to create 4 patties. Cook on both sides until crisp. 6. Put pan with bread slices into the oven to lightly toast. 7. When egg-potato patties are done immediately top with slices of cheddar cheese. Set aside. 8. Remove lightly toasted bread from the oven. 9. To assemble sandwiches: lay four slices of bread on flat work surface. Top each slice of bread with one of the egg-potato-melted cheese patties. Place two Swaggerty’s sausage patties on each and top with 2nd slice of toasted Cinnamon Bread. 10. Serve warm as a handheld sandwich or plated with a drizzle of maple syrup. To Serve This breakfast sandwich has it all….eggs, potatoes, cheese, Swaggerty’s Farm Sausage & wonderfully toasted Cinnamon Bread. 4 servings 15 min prep time 10 min cook time -

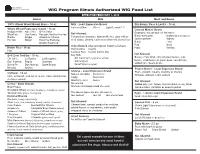

WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List

State of Illinois Department of Human Services WIC Program Illinois Authorized WIC Food List EFFECTIVE FEBRUARY 1, 2019 Grains Milk Meat and Beans 100% Whole Wheat Bread, Buns - 16 oz Milk - Least Expensive Brand Dry Beans, Peas & Lentils - 16 oz Fat Free/Skim Whole Light/Lowfat/1% Whole Wheat Pasta (any shape) - 16 oz Canned Mature Beans Hodgson Mill Racconto Great Value Examples include but not limited to: ShurFine Our Family Ronzoni Healthy Harvest Not Allowed: Black-eyed peas Garbanzo (chickpeas) Barilla Kroger America’s Choice Flavored or chocolate, buttermilk, rice, goat milk or Hy-Vee Meijer Essential Everyday shelf stable, almond, cashew or other milk alternatives Great northern Kidney Simply Balanced Black Lima Only Allowed when printed on Food Instrument: Red Navy Brown Rice - 16 oz Half Gallons Quarts Pinto Refried Plain Lactose Free Instant Nonfat Dry Not Allowed: Soft Corn Tortillas - 16 oz Soy Milk Soups of any kind, canned green beans, wax Chi Chi’s La Burrita La Banderita 8th Continent (original or vanilla) beans, snap beans or green peas, seasonings, Don Pancho Pepito Guerrero Silk (original) added fats, meats or oils Santa Fe Don Marcos Store Brand Great Value (original) Mission Azteca Peanut Butter - Least Expensive Brand Cheese - Least Expensive Brand Oatmeal - 16 oz Plain, smooth, creamy, crunchy or chunky Natural Cheddar Provolone All types allowed in low sodium Old Fashioned, Traditional, Quick-Cook, Rolled Oats Colby Muenster (no flavors added) Monterey Jack Swiss Not Allowed: Cereal - Store Brands Mozzarella Added -

Part I Paper 8 British Economic and Social

PART I PAPER 8 BRITISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY, 1050-c. 1500 2019-20 READING LIST FOR STUDENTS & SUPERVISORS Man’s head, fourteenth century, a carving in Prior Crauden’s chapel (1320s), Ely cathedral 1 Part I Paper 8 2019-20 The period covered by this paper was one of dramatic change in British economic and social life. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were a time of marked economic development and creativity, and saw the expansion of agricultural output, towns, trade and industry. Famine and plague followed in the fourteenth century, leading to a very different era of stagnation and social upheaval in the later middle ages. Overall, it is now generally agreed that the period studied in this course laid essential foundations for Britain’s exceptional economic trajectory in later centuries. This course aims to provide students with a sense of the broader trends of the period 1050-1500, as well as the chance to look in depth at important problems and debates. By the end of the course students will also be able to reflect on the exciting challenges involved in studying the society and economy of an era before censuses, government statistics, and printing. Paper 8 is made up of 24 topics, such as ‘The Black Death’, ‘Town life’, and ‘War and society’. Students, in consultation with their supervisors, can choose which of these topics they wish to study for weekly supervisions. The 24 topics represent a mix of economic and social history. Across Michaelmas and Lent terms, there will be two series of introductory lectures, followed by lectures on each of the 24 topics.