Cholera Epidemiology and Response Factsheet Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

The Boko Haram Conflict in Cameroon Why Is Peace So Elusive? Pr

Secur nd ity a S e e c r i a e e s P FES Pr. Ntuda Ebode Joseph Vincent Pr. Mark Bolak Funteh Dr. Mbarkoutou Mahamat Henri Mr. Nkalwo Ngoula Joseph Léa THE BOKO HARAM CONFLICT IN CAMEROON Why is peace so elusive? Pr. Ntuda Ebode Joseph Vincent Pr. Mark Bolak Funteh Dr. Mbarkoutou Mahamat Henri Mr. Nkalwo Ngoula Joseph Léa THE BOKO HARAM CONFLICT IN CAMEROON Why is peace so elusive? Translated from the French by Diom Richard Ngong [email protected] © Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Yaoundé (Cameroun), 2017. Tél. 00 237 222 21 29 96 / 00 237 222 21 52 92 B.P. 11 939 Yaoundé / Fax: 00 237 222 21 52 74 E-mail : [email protected] Site : www.fes-kamerun.org Réalisation éditoriale : PUA : www.aes-pua.com ISBN: 978-9956-532-05-3 Any commercial use of publications, brochures or other printed materials of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung is strictly forbidden unless otherwise authorized in writing by the publisher This publication is not for sale All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photo print, microfilm, translation or other means without written permission from the publisher TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ………………………………………………….....……………....................…………..................... 5 Abbreviations and acronyms ………………………………………...........…………………………….................... 6 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………....................………………....….................... 7 Chapter I – Background and context of the emergence of Boko Haram in Cameroon ……………………………………………………………………………………....................………….................... 8 A. Historical background to the crisis in the Far North region ……………..……….................... 8 B. Genesis of the Boko Haram conflict ………………………………………………..................................... 10 Chapter II - Actors, challenges and prospects of a complex conflict ……………....... 12 A. Actors and the challenges of the Boko Haram conflict …………………………….....................12 1. -

Cameroon, Third Quarter 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Updated 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 20 December 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 15 December 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 85 64 159 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 81 52 284 Development of conflict incidents from September 2016 to September Strategic developments 24 0 0 2018 2 Riots/protests 8 0 0 Methodology 3 Remote violence 4 1 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Conflict incidents per province 4 Total 203 117 447 Localization of conflict incidents 4 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from September 2016 to September 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 15 December 2018). 2 CAMEROON, THIRD QUARTER 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - UPDATED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 20 DECEMBER 2018 Methodology Geographic map data is primarily based on GADM, complemented with other sources if necessary. -

Christian Churches and the Boko Haram Insurgency in Cameroon: Dilemmas and Responses

religions Article Christian Churches and the Boko Haram Insurgency in Cameroon: Dilemmas and Responses Lang Michael Kpughe Department of History, Higher Teacher Training College, University of Bamenda, Bambili-Bamenda 39, Cameroon; [email protected] Received: 15 June 2017; Accepted: 1 August 2017; Published: 7 August 2017 Abstract: The spillover of the terrorist activities of Boko Haram, a Nigerian jihadi group, into Cameroon’s north has resulted in security challenges and humanitarian activity opportunities for Christian churches. The insurgents have attacked and destroyed churches, abducted Christians, worsened Muslim-Christian relations, and caused a humanitarian crisis. These ensuing phenomena have adversely affected Christian churches in this region, triggering an aura of responses: coping strategies, humanitarian work among refugees, and inter-faith dialogue. These responses are predicated on Christianity’s potential as a resource for peace, compassion, and love. In this study we emphasize the role of Christian churches in dealing with the Boko Haram insurgency. It opens with a presentation of the religious configuration of Cameroon, followed by a contextualization of Boko Haram insurgency in Cameroon’s north. The paper further examines the brutality meted out on Christians and church property. The final section is an examination of the spiritual, humanitarian, and relief services provided by churches. The paper argues that although Christian churches have suffered at the hands of Boko Haram insurgents, they have engaged in various beneficial responses underpinned by the Christian values of peace and love. Keywords: Cameroon; terrorism; religion; Islam; Boko Haram; Christian Churches; peace 1. Introduction There is a consensus in the available literature that all religions have within the practices ensuing from their foundational beliefs both violent and peaceful tendencies (Bercovitch and Kadayifci-Orellana 2009; Chapman 2007; Fox 1999). -

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018

Cameroon |Far North Region |Displacement Report Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 Cameroon | Far North Region | Displacement Report | Round 15 | 03– 15 September 2018 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries1. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration, advance understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration Cameroon Mission Maroua Sub-Office UN House Comice Maroua Far North Region Cameroon Tel.: +237 222 20 32 78 E-mail: [email protected] Websites: https://ww.iom.int/fr/countries/cameroun and https://displacement.iom.int/cameroon All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 1The maps included in this report are illustrative. The representations and the use of borders and geographic names may include errors and do not imply judgment on legal status of territories nor acknowledgement of borders by the Organization. -

Case Study of Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Public Policy Response to Violence: Case Study of Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria Emmanuel Baba Mamman Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Emmanuel Baba Mamman has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Timothy Fadgen, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Victoria Landu-Adams, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Eliesh Lane, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract Public Policy Response to Violence: Case Study of Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria by Emmanuel Baba Mamman MPA, University of Ilorin, 1998 BSc (Ed), Delta State University, Abraka, 1992 Final Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University September 2020 Abstract The violence of the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria has generated an increased need for public policy responses. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Cameroon/2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights October 2019 2,300,000 • In initial response to serious flooding in Zina and Kai Kai districts of # of children in need of humanitarian Far North Region, UNICEF distributed emergency supplies including assistance WASH and Dignity Kits, plastic sheeting, water filters and aqua-tabs benefitting over 2,000 people. 4,300,000 # of people in need • Over 18,400 school aged children in the North-West, South-West, (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019) Littoral and West regions are attending education with a teacher trained in psychosocial support, conflict and disaster risk reduction Displacement using the UNICEF umbrella-based methodology. 536,107 • In response to the ongoing armed conflict impacting districts # of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in adjoining NE Nigeria, UNICEF provided psychosocial support to the North-West and South-West regions 3,314 children (1,407 girls and 1,907 boys) in community-based Child (IOM Displacement Monitoring, #16) {Does this include the ones in Littoral and West? If yes, this should be Friendly Spaces (CFS) and other secure spaces through its clarified} implementing partners in Logone-and-Chari, Mayo Sava and Mayo 381,444 Tsanaga divisions of Far North Region. # of Returnees in the North-West and South-West regions (IOM Displacement Matrix, August 2019) UNICEF’s Response with Partners 372,854 # of IDPs and Returnees in the Far-North region Sector Total UNICEF Total (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix 18, April -

Displacement Tracking Matrix I Dtm

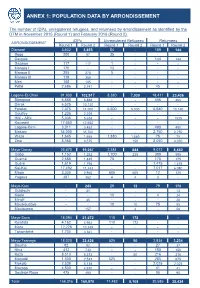

ANNEX 1: POPULATION DATA BY ARRONDISSEMENT The number of IDPs, unregistered refugees, and returnees by arrondissement as identified by the DTM in November 2015 (Round 1) and February 2016 (Round 2). IDPs Unregistered Refugees Returnees ARRONDISSEMENT Round 1 Round 2 Round 1 Round 2 Round 1 Round 2 Diamaré 3,602 3,655 54 - 189 144 Bogo 200 57 35 - - - Dargala - - - - 144 144 Gazawa 117 117 1 - - - Maroua I 170 - 13 - - - Maroua II 205 270 5 - - - Maroua III 119 365 - - - - Meri 105 105 - - - - Pétté 2,686 2,741 - - 45 - Logone-Et-Chari 91,930 102,917 8,380 7,030 18,411 23,436 Blangoua 6,888 6,888 - - 406 406 Darak 6,525 10,120 - - - - Fotokol 7,375 11,000 6,500 5,000 6,640 10,140 Goulfey 1,235 2,229 - - - - Hilé - Alifa 5,036 5,638 - - - 1525 Kousséri 17,650 17,650 - - - - Logone-Birni 3,011 3,452 - - 490 490 Makary 34,000 35,700 - - 2,750 2,750 Waza 1,645 1,665 1,880 1,880 75 75 Zina 8,565 8,575 - 150 8,050 8,050 Mayo-Danay 26,670 19,057 2,384 844 9,072 8,450 Gobo 1,152 1,252 1,700 235 390 595 Guémé 2,685 1,445 75 - 175 175 Guéré 1,619 1,795 - - 1,475 1,475 Kai-Kai 17,492 11,243 - - 7,017 6,080 Maga 3,335 2,960 605 605 12 125 Yagoua 387 362 4 4 3 - Mayo-Kani - 243 29 12 79 170 Guidiguis - 41 - 13 Kaélé - - 19 - 4 24 Mindif - 45 - - - 20 Moulvoudaye - - 10 10 75 55 Moutourwa - 157 - 2 - 58 Mayo-Sava 18,094 21,672 110 172 - - Kolofata 4,162 4,962 110 172 - - Mora 12,228 13,349 - - - - Tokombéré 1,704 3,361 - - - - Mayo-Tsanaga 18,020 22,426 525 50 2,834 3,234 Bourha 82 92 - - 27 37 Hina 412 730 - - 150 150 Koza 8,513 8,513 - 50 216 216 Mogodé 1,500 2,533 525 - 285 675 Mokolo 2,538 5,138 - - 2,025 2,025 Mozogo 4,500 4,930 - - 41 41 Soulèdé-Roua 475 490 - - 90 90 TotalDTM Cameroon 158,316 Round169,970 1 – November 11,482 2015 8,108 30,585 35,434 1 ANNEXE 2: LOCATIONS OF DISPLACED INDIVIDUALS Location of internally displaced persons, unregistered refugees, and returnees in the Far North region. -

Cameroun |Région De L'extrême-Nord |Rapport Sur Les Déplacements Round 22

Cameroun |Région de l’Extrême-Nord |Rapport sur les Déplacements Round 22 | 12 au 31 mars 2021 Cameroun | Région de l’Extrême-Nord | Rapport sur les déplacements | Round 21 | 12 au 31 mars 2021 Les avis exprimés dans ce rapport sont ceux des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement les points de vue de l’Organisation Internationale pour les Migrations (OIM). Des donateurs et des partenaires : L’OIM croit profondément que la migration humaine et ordonnée est bénéfique pour les migrants et la société. En tant qu’organisation intergouvernementale, l’OIM agit avec ses partenaires de la communauté internationale afin d’aider à résoudre les problèmes opérationnels que pose la migration ; de faire mieux comprendre quels en sont les enjeux ; d’encourager le développement économique et social grâce à la migration et de préserver la dignité humaine et le bien-être des migrants. Les cartes fournies le sont uniquement à titre illustratif. Les représentations ainsi que l’utilisation des frontières et des noms géographiques sur ces cartes peuvent comporter des erreurs et n’impliquent ni jugement sur le statut légal d’un territoire, ni reconnaissance ou acceptation officielles de ces frontières de la part de l’OIM. Organisation Internationale pour les Migrations Mission du Cameroun Sous-Bureau de Maroua UN House Comice Maroua Région de l’Extrême-Nord Cameroun Tél. : +237 222 20 32 78 E-mail : [email protected] Sites web : https://ww.iom.int/fr/countries/cameroon, https://displacement.iom.int/cameroon, www.GlobalDTM.info/cameroon, https://dtm.iom.int/cameroon Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de ce document ne peut être reproduite, archivée ou transmise sous quelque forme et de quelque façon, électronique, mécanique, photocopie, enregistrement ou autre sans l’autorisation préalable de l’éditeur. -

Cameroon: Measles

Information bulletin n° 1 Cameroon: Glide EP-2009-000021-CMR 22 January, 2008 Measles This bulletin has been issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. The Federation is not seeking funding or other assistance from donors for this operation. The Cameroon Red Cross National Society will, however, accept direct assistance to provide support to the affected population. An outbreak of measles occurred in Northern Cameroon since early 2008, and intensified with the arrival of Chadian refugees in that locality in February 2008. Since then, a total number of 355 cases of measles have been registered in the region, including 64 cases in January 2009. The Northern region of Cameroon is divided into 15 health zones, 10 of which have each registered at least one case of measles since early 2009. The average age of the people affected is 3.5 years, and 50% of the victims are 3 years old. 75% of the victims are below the age of 5, with the youngest being just 4 months old. Government organized an immunization campaign in 2008, but several families deliberately refused to get their children vaccinated. 84% of measles cases registered so far are those children who failed to be vaccinated in 2008, the majority of whom are male children. Since 2008, 17 people have died of measles in that locality. The Cameroon Red Cross Society (CRCS), with the support of the Federation’s Central Africa Regional Representation (CARREP) in Yaoundé (Cameroon) has already started sensitizing the populations to the signs and symptoms of the disease, and referring cases identified to the nearest health centre. -

Recovery and Peace Consolidation Strategy for Public Disclosure Authorized Northern and East Cameroon 2018–2022 Public Disclosure Authorized

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Recovery and Peace Consolidation Strategy for Public Disclosure Authorized Northern and East Cameroon 2018–2022 Public Disclosure Authorized Recovery and Peace Consolidation Strategy for Northern and East Cameroon 2018–2022 The Recovery and Peace Consolidation Strategy for Northern and East Cameroon has been produced by the government of Cameroon with technical support from staff of the World Bank Group, the United Nations, and the European Union. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in the Strategy do not necessarily constitute the views or formal recommendations of the three institutions on all issues, nor do they reflect the views of the governing bodies of these institutions or their member states. Photos: Odilia Hebga / World Bank Editor: Beth Rabinowitz Design/layout: Nita Congress Contents Foreword.................................................... viii Abbreviations ................................................ ix Strategy development team ..................................... x Executive summary ............................................ xii 1: Introduction ................................................. 2 RATIONALE . 3 THE RPC PROCESS AND ITS OBJECTIVES . 4 PRIORITY THEMES . 5 METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH . 6 PRIORITIZATION . 7 ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT . .8 2: Context analysis ............................................ 10 OVERVIEW OF CONTEXT . 11 ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF THE CRISES, STRUCTURAL VULNERABILITY, AND FACTORS OF RESILIENCE . .15