Images of Exhibition and Encounter (London: Palgrave Macmillan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied. -

This Is the File GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013

This is the file GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013 -=] INTRODUCTION [=- This catalog is a plain text compilation of our eBook files, as follows: GUTINDEX.2013 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013 with eBook numbers starting at 41750. GUTINDEX.2012 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012 with eBook numbers starting at 38460 and ending with 41749. GUTINDEX.2011 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011 with eBook numbers starting at 34807 and ending with 38459. GUTINDEX.2010 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010 with eBook numbers starting at 30822 and ending with 34806. GUTINDEX.2009 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009 with eBook numbers starting at 27681 and ending with 30821. GUTINDEX.2008 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2008 with eBook numbers starting at 24098 and ending with 27680. GUTINDEX.2007 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007 with eBook numbers starting at 20240 and ending with 24097. GUTINDEX.2006 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006 with eBook numbers starting at 17438 and ending with 20239. -

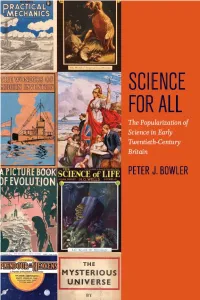

Science for All

SCIENCE FOR ALL Science for All :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: The Popularization of Science in Early Twentieth-Century Britain PETER J. BOWLER The University of Chicago Press : Chicago and London Peter J. Bowler is professor of history of science in the School of History and Anthropology at Queen’s University, Belfast. He is the author of several books, including with the University of Chicago Press: Life’s Splendid Drama: Evolutionary Biology and the Reconstruction of Life’s Ancestry, 1860–1940 and Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain; and coauthor of Making Modern Science. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2009 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bowler, Peter J. Science for all: the popularization of science in early twentieth- century Britain / Peter J. Bowler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-06863-3 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Science news— Great Britain—History—20th century. 2. Communication in science—Great Britain—History—20th century. I. Title. q225.2.g7b69 2009 509.41'0904—dc22 2008055466 a The paper used in this publication meets the minimum re- quirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992. -

Studi Interculturali 1/2017 Issn 2281-1273

STUDI INTERCULTURALI 1/2017 ISSN 2281-1273 MEDITERRÁNEA - CENTRO DI STUDI INTERCULTURALI DIPARTIMENTO DI STUDI UMANISTICI - UNIVERSITÀ DI TRIESTE Studi Interculturali 1/2017 Chuck Berry (Saint Louis, 18 ottobre 1926 - Saint Charles, 18 marzo 2017) (foto: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Getty Images>) «Meanwhile, I was still thinkin' If it's a slow song, we'll omit it If it's a rocker, then we'll get it And if it's good, she'll admit it C'mon queenie, let's get with it» Studi Interculturali #1 /2017 issn 2281-1273 - isbn 978-0-244-60518-6 MEDITERRÁNEA - CENTRO DI STUDI INTERCULTURALI Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Università di Trieste A cura di Mario Faraone e Gianni Ferracuti. Grafica e webmaster: Giulio Ferracuti www.interculturalita.it Studi Interculturali è un’iniziativa senza scopo di lucro. I fascicoli della rivista sono distribuiti gratui- tamente in edizione digitale all’indirizzo www.interculturalita.it. Nello stesso sito può essere richiesta la versione a stampa (print on demand). © Copyright di proprietà dei singoli autori degli articoli pubblicati: la riproduzione dei testi deve essere autorizzata. La foto di Chuck Berry (Gijsbert Hanekroot/Getty Images) è tratta da <http://www.scoopnest.com/user/TheAVClub/843240562350329856>. Mediterránea ha il proprio sito all’indirizzo www.ilbolerodiravel.org. Il presente fascicolo è stato chiuso in redazione in data 28.04.2017. Gianni Ferracuti Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Università di Trieste Androna Campo Marzio, 10 - 34124 Trieste SOMMARIO ILARIA ROSSINI: Dislocazione nello spazio, nel tempo e nello spirito. Pagine di scrittura migrante .............................. 7 ANNA DI SOMMA: «Meditazioni sudamericane»: La tappa sudamericana dell’onto-antropo-logia di Ernesto Grassi ..................................................... -

Julian Huxley - Wikipedia

3/4/2021 Julian Huxley - Wikipedia Julian Huxley Sir Julian Sorell Huxley FRS[1] (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary Sir biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. He was secretary of the Zoological Society of Julian Huxley London (1935–1942), the first Director of UNESCO, a founding member of the World Wildlife Fund FRS and the first President of the British Humanist Association. Huxley was well known for his presentation of science in books and articles, and on radio and television. He directed an Oscar-winning wildlife film. He was awarded UNESCO's Kalinga Prize for the popularisation of science in 1953, the Darwin Medal of the Royal Society in 1956,[1] and the Darwin–Wallace Medal of the Linnaean Society in 1958. He was also knighted in that same year, 1958, a hundred years after Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace announced the theory of evolution by natural selection. In 1959 he received a Special Award of the Lasker Foundation in the category Planned Parenthood – World Population. Huxley was a prominent member of the British Eugenics Society and was its president from 1959 to 1962. Contents Life Personal life Early career Mid career Julian Huxley as Fellow of New Later career College, Oxford 1922 Special themes Personal details Evolution Born Julian Sorell Huxley Personal influence 22 June 1887 Evolutionary synthesis London, England Evolutionary progress Died 14 February 1975 Secular humanism -

Margaret Storm Jameson and the Spanish Civil War: the Fight for Human Values

JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES - VOLUME 5-6 (2005-2008), 13-29 MARGARET STORM JAMESON AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR: THE FIGHT FOR HUMAN VALUES JENNIFER BIRKETT University of Birmingham ABSTRACT. Spain is not generally thought of as a significant theme in Jameson’s writing, or her political formation. But careful study of her life and writing discloses numerous connections to the country from the early 1930s onwards, and No Victory for the Soldier (1938), the novel she published under the pseudonym of James Hill, in the 1930s, closes with a lengthy section on the Spanish Civil War. The tragic heroism of the Republic at war provides the ideal context for Jameson’s exploration of the capacity of modernist art, or rather, modernist artists (the Auden generation) to speak in the name of the future of the common man. Spain, and especially the Basque country, fighting the fascist war machine, is one of the last repositories of humane living and European values: reason, justice, humanity and decency. “Does this mean anything to you?” (Hill 1939: 341) Through the mouth of Sergeant Derio, the Basque professor of philosophy waiting for the German and Italian bombs to fall on Bilbao, Storm Jameson expressed the hopes pinned on Spain and its revolution. Here was the last opportunity of seeing the values she nostalgically assigned to pre-industrial England enshrined in the making of modern, metropolitan Europe. As Derio tells John Knox, the musician helping to man the Republican field hospitals: “Here we still cared more for human beings than for anything they can make or possess. -

Knowledge and Pleasure at Regent's Park

KNOWLEDGE AND PLEASURE AT REGENT'S PARK The Gardens of the Zoological Society of London during the Nineteenth Century Sofia Åkerberg KNOWLEDGE AND PLEASURE AT REGENT'S PARK The Gardens of the Zoological Society of London during the Nineteenth Century Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av rektorsämbetet vid Umeå universitet för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen offentligen försvaras i Humanisthuset, hörsal F tisdagen den 4 december 2001, klockan 10.15 av Sofia Åkerberg Sofia Åkerberg, Knowledge and Pleasure at Regent's Park: The Gardens of the Zoobgical Society of London during the Nineteenth Century English text Department of Historical Studies, Umeå University, SE-901 87 Umeå, Sweden Monograph 2001. 254 pages Idéhistoriska skrifter nr 36 ISBN: 91-7305-147-0 ISSN: 0280-7646 Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the Zoological Gardens of the Zoological Society of London (f. 1826) in the nineteenth century. Located in Regent s Park, it was the express purpose of the Gardens (f. 1828) to function as a testing-ground for acclimatisation and to demonstrate the scientific impor tance of various animal species. The aim is t o analyse what the Gardens signified as a recreational, educational and scientific institution in nineteenth-century London by considering them from four different perspectives: as a pan of a newly-founded society, as a part of the leisure culture of mid-Victorian London, as a medi ator of popular zoology and as a constituent of the Zoological Society's scientific ambitions. After an introduction which describes the devlopment of European zoos, Chapter two recapitu lates the early years of the Society and the Gardens. -

“Once Through the Gate, Face Right. the Deer House, the Camel House

1 “Once through the gate, face right. The Deer House, The Camel House, The Giraffe House, The Cattle and Zebra House and The Antelope House will all be found on your left across a canal and a wild ravine. Water Bus rides on the artificial river start at ten. As you face your right you see a path before you. Take it. You pass, on your right, The Owls Aviary and The Pheasantry. All of the pheasants have gone away and you can count up fourteen empty cages, waiting. You can listen to the wind across The Reptile House, The Reptiliary, The Gentlemen’s Toilets, The Charles Clore Pavilion for Mammals and Moonlight World. Ahead of you a great fence of wide-mesh wire catches the wind; it is a huge crazy sail that is warped to the ground like a tent and has a door of brushed aluminum. It peaks in twenty places, it bulges at its sides; thick steel pipes at strange angles just like spars and when you walk inside, saying, “You go first. You come first, you always came first for me. You know that,” the noise that she makes for you by listening in silence, saying nothing, even when you try to smirk your sudden words away, is lost. For you are in The Snowdon Aviary, opened in 1965, the first out-of-doors walk- through aviary in The London Zoo, which houses many birds from a variety of natural habitats. The Aviary was designed by Lord Snowdon in association with Mr. Cedric Price and Mr. -

Thomas Henry Huxley – Wikipedia

Thomas Henry Huxley – Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Henry_Huxley Thomas Henry Huxley (* 4. Mai 1825 in Ealing, Middlesex; † 29. Juni 1895 in Eastbourne) war ein britischer Biologe und vergleichender Anatom, Bildungsorganisator und Hauptvertreter des Agnostizismus, dessen Begriff er prägte und durchsetzte. Als einflussreicher Unterstützer des Empirismus David Humes und der Evolutionstheorie Charles Darwins (was zu seinem Beinamen Darwin’s Bulldog führte) hatte er zusätzlich zu seinen eigenen umfangreichen Forschungen, Lehrbüchern und Essays sehr großen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Naturwissenschaften im 19. Jahrhundert. Thomas Henry Huxley (Fotografie) Leben und Wirken Ehrungen Schriften (Auswahl) Literatur Weblinks Einzelnachweise Thomas Henry Huxley wurde am 4. Mai 1825 als Sohn eines Lehrers[1] im später zu London gehörenden Ealing geboren. Seine anglikanischen Eltern George Huxley und Thomas Henry Huxley (1874) Rachel Withers hatten 1810 geheiratet. Thomas Henry war ihr siebtes Kind und gleichzeitig das jüngste überlebende von insgesamt acht.[2] Huxley trat 1841 als Gehilfe in die Praxis eines Schwagers, des Arztes James Godwin Scott, in London ein und besuchte parallel Vorlesungen am Sydenham College.[3] Am 1. Oktober 1842 nahm er am Charing Cross Hospital das Studium der Medizin auf,[4] welches er 1845 mit dem akademischen Grad eines Bacc. med. der University of London abschloss.[5] Im Anschluss verdingte er sich bei der Royal Navy. Nach kurzer Tätigkeit am Royal Naval Hospital in Haslar vermittelte ihm sein dortiger -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Psychotropes Models of Authorship, Psychopathology, and Molecular Politics in Aldous Huxley and Philip K. Dick Chris John Rudge A thesis submitted to the Department of English and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or institute of higher learning.