Moneyball Book Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11-05-2018 A's Billy Beane Named

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Nov. 5, 2018 Billy Beane named MLB Executive of the Year OAKLAND, Calif. – Oakland A’s Executive Vice President of Baseball Operations, Billy Beane, has been named the 2018 MLB Executive of the Year. This is the first year this official award has been bestowed by MLB. The A’s finished the 2018 season with a 97-65 record—fourth best in baseball—after finishing last in the AL West each of the previous three seasons. The club reached the postseason for the fourth time in the last seven years despite losing 21 players—including nine starting pitchers—to the disabled list. Beane has been named Major League Executive of the Year by Baseball America two times (2002; 2013) and The Sporting News Executive of the Year twice as well (1999; 2012). He also earned MLB.com’s Greatness in Baseball Yearly (GIBBY) Award as the 2012 MLB Executive of the Year and the 2012 Legacy Awards’ Rube Foster Award as AL Executive of the Year, presented by the Negro League Baseball Museum. Under his watch, the A’s have compiled a 1793-1607 (.527) record over the last 21 years, which is the fourth-best record in the American League and seventh best in all of baseball during that time frame. The A’s have six American League West titles (2000; 2002-03; 2006; 2012-13) and have secured three AL Wild Card spots (2001; 2014; 2018) during that span. His teams have posted 90 or more wins in nine of the last 19 years. The A’s nine postseason appearances since the 2000 season are sixth most among all Major League teams, trailing only New York-AL (15), St. -

Brian Mccrea Brmccrea@Ufl

IDH 2930 Section 1D18 HNR Read Moneyball Tuesday 3 (9:35-10:25 a. m.) Little Hall 0117 Brian McCrea brmccrea@ufl. edu (352) 478-9687 Moneyball includes twelve chapters, an epilogue, and a (for me) important postscript. We will read and discuss one chapter a week, then finish with a week devoted to the epilogue and to the postscript. At our first meeting we will introduce ourselves to each other and figure out who amongst us are baseball fans, who not. (One need not have an interest in baseball to enjoy Lewis or to enjoy Moneyball; indeed, the course benefits greatly from disinterested business and math majors.) I will ask you to write informally every class session about the reading. I will not grade your responses, but I will keep a word count. At the end of the semester, we will have an Awards Ceremony for our most prolific writers. While this is not a prerequisite, I hope that everyone has looked at Moneyball the movie (starring Brad Pitt as Billy Beane) before we begin to work with the book. Moneyball first was published—to great acclaim—in 2003. So the book is fifteen-year’s old, and the “new” method of evaluating baseball players pioneered by Billy Beane has been widely adopted. Beane’s Oakland A’s no longer are as successful as they were in the early 2000s. What Lewis refers to as “sabremetrics”—the statistical analysis of baseball performance—has expanded greatly. Baseball now has statistics totally different from those in place as Lewis wrote: WAR (Wins against replacement), WHIP (Walks and hits per inning pitched) among them. -

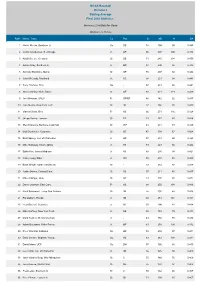

NCAA Baseball Division I Batting Average Final 2002 Statistics

NCAA Baseball Division I Batting Average Final 2002 Statistics Minimum 2.5 At-Bats Per Game Minimum 75 At-Bats Rank Name, Team CL Pos G AB H BA 1 Rickie Weeks, Southern U. So. SS 54 198 98 0.495 2 Curtis Granderson, Ill.-Chicago Jr. OF 55 207 100 0.483 3 Khalil Greene, Clemson Sr. SS 71 285 134 0.470 4 Antoin Gray, Southern U. Jr. OF 54 205 92 0.449 5 Anthony Bocchino, Marist Sr. OF 55 207 92 0.444 6 John McCurdy, Maryland Jr. SS 54 221 98 0.443 7 Terry Trofholz, TCU So. - 57 213 94 0.441 8 Steve Stanley, Notre Dame Sr. OF 68 271 119 0.439 9 Joe Wickman, UNLV Fr. SP/RP 46 142 62 0.437 10 Tom Merkle, New York Tech Sr. 3B 52 186 80 0.430 11 Vincent Sinisi, Rice Fr. 1B 66 271 116 0.428 12 Gregg Davies, Towson Sr. 1B 51 187 80 0.428 13 Wes Timmons, Bethune-Cookman Sr. INF 61 214 91 0.425 14 Matt Buckmiller, Columbia Sr. OF 47 158 67 0.424 15 Brett Spivey, Col. of Charleston Jr. OF 57 213 90 0.423 16 Mike Galloway, Miami (Ohio) Jr. 1B 59 223 94 0.422 17 Eddie Kim, James Madison Jr. 1B 60 235 99 0.421 18 Casey Long, Rider Jr. INF 55 210 88 0.419 19 Brian Wright, North Carolina St. Sr. - 59 232 97 0.418 20 Justin Owens, Coastal Caro. Sr. 1B 57 211 88 0.417 21 Mike Arbinger, Ohio Sr. -

National Collegiate Baseball Writers Newsletter National Collegiate Baseball Writers Newsletter

NATIONAL COLLEGIATE BASEBALL WRITERS NEWSLETTER (Volume 41, No. 1, January 30, 2002) Barry on Baseball NCBWA President’s Message by Barry Allen The wait is finally over. The 2002 college baseball season has officially begun. While most of the schools do not open play until Feb. 1, 2002, there are some that have already opened their seasons entering the final week of January. The 2002 college baseball season promises to be one of the most exciting seasons in memory. Can Miami make it three in a row at Rosenblatt Stadium? The defending champs return a number of key players and will play one of the nation's most demanding schedules. How will baseball at Alex Box Stadium differ now that legendary Skip Bertman is no longer in the first base dugout? New Tigers skipper Ray "Smoke" Laval opened practice on Saturday, Jan. 19, and is the favorite to win the SEC in a vote by the league's 12 head coaches. Can Nebraska claim its third straight 50-win season and turn Rosenblatt Stadium into another sea of red at the 2003 College World Series? Will Stanford journey back to America's heartland again this season, boasting another talented team under Mark Marquess? Who will be the eight teams to fight for the 2003 national championship in June? All of these questions will be answered over the course of the next 21 weeks as the college baseball season unfolds. It promises to be an exciting year. Off the field, there is excitement, too. There will be a trip to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum this year as the annual CoSIDA convention will be held in Rochester, N.Y. -

BILLY BEANE Executive Vice President of Baseball Operations for the Oakland A’S

BILLY BEANE Executive Vice President of Baseball Operations for the Oakland A’s AT THE PODIUM Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game Billy Beane’s “Moneyball” philosophy has been adopted by organizations of all sizes, across all industries, as a way to more effectively, efficiently, and profitably manage their assets, talent, and resources. He has helped to shape the way modern businesses view and leverage big data and employ analytics for long-term success. illy Beane is considered In his signature talk, which explores his innovative, winning approach to Bone of the most management and leadership, Beane: progressive and talented baseball executives in the • Describes How He Disrupted The World of Baseball by Taking the game today. As General Undervalued and Underpaid Oakland A’s to 6 American League West Manager of the Oakland Division Titles A’s, Beane shattered traditional MLB beliefs that • Elaborates upon his now-famous “Moneyball Methodology”, which big payrolls equated more Numerous Companies Have Implemented in order to Identify and Re- wins by implementing a Purpose Undervalued Assets statistical methodology that led one of the worst • Demonstrates How to Win Against Companies That Have Bigger teams in baseball—with Budgets, More Manpower, and Higher Profiles one of the lowest payrolls— to six American League • Discusses Attaining a Competitive Advantage to Stimulate a Company’s West Division Titles. That Growth strategic methodology has come to be known as the • Illustrates the Parallels Between Baseball and Other Industries that “Moneyball” philosophy, Require Top-Tier, Methodical Approaches to Management named for the bestselling book and Oscar winning film • Emphasizes the Need to Allocate Resources and Implement Truly chronicling Beane’s journey Dynamic Analytics Programs from General Manager to celebrated management • Delineate How to Turn a Problem into Profit and Make Those Returns genius. -

Moneyball: Hollywood and the Practice of Law by Sharon D

Moneyball: Hollywood and the Practice of Law by Sharon D. Nelson, Esq. and John W. Simek © 2016 Sensei Enterprises, Inc. Moneyball: The Book and the Movie We are not going to confess how many times we’ve watched Moneyball. It’s embarrassing – and still, when it comes on, we are apt to look at one another, smile and nod in silent agreement – yes, again please. The very first time we saw Moneyball, we knew it would crop up in an article. The movie’s use of data analytics in baseball immediately prompted us to start talking about how some of the lessons of Moneyball applied to the legal sector. We promise you that we came up with the title of this column ourselves, but as we began our research, we were shocked at how many others have had the same idea. In fact, a CLE at this year’s Legal Tech had a very similar name – and several articles on data analytics in the law did too. So, if you have thus far missed seeing Moneyball, let us set the stage. The book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game was written by Micahel Lewis and published in 2003. It is about baseball – specifically about the Oakland Athletics baseball team and its general manager, Billy Beane. The cash-strapped (and losing) Athletics did not look promising until Beane had an epiphany. Perhaps the conventional wisdom of baseball was wrong. Perhaps data analytics could reveal the best players at the best price that could come together as a winning team. -

SEC Tournament Record Book

SEC Tournament Record Book SEC TOURNAMENT FORMAT HISTORY 2012 Years: 42nd tournament in 2018 With the addition of Texas A&M and Missouri for 2013, the SEC expanded the tournament from 8 to 10 teams. Total Games Played: 515 2013–present 1977–1986 The 2013 format saw another expansion by two teams, bringing the total number From 1977–1986, the tournament consisted of four teams competing in a double of participants to 12. Seeds five through 12 play a single-elimination opening elimination bracket. The winner was considered the conference’s overall cham- round, followed by the traditional double-elimination format until the semifinals, pion. when the format reverts to single-elimination. 1987–1991 Host locations In 1987, the tournament expanded to 6 teams, while remaining a double-elimi- Hoover, Ala. 21 (1990, 1996, 1998-Present) nation tournament. Beginning with the 1988 season, the winner was no longer Gainesville, Fla. 5 (1978, 1980, 1982, 1984, 1989) considered the conference’s overall champion, although the winner continued Starkville, Miss. 5 (1979, 1981, 1983, 1988, 1995 Western) to receive the conference’s automatic bid to the NCAA Tournament. In 1990, Baton Rouge, La. 4 (1985-86, 1991, 1993 Western) however, the conference did not accept an automatic bid after lightning and Oxford, Miss. 2 (1977, 1994 Western) rainfall disrupted the tournament’s championship game and co-champions were Athens, Ga. 1 (1987) declared. Columbia, S.C. 1 (1993 Eastern) Knoxville, Tenn. 1 (1995 Eastern) 1992 Lexington, Ky. 1 (1994 Eastern) With the addition of Arkansas and South Carolina to the conference, the SEC held Columbus, Ga. -

Moneyball' Bit Player Korach Likes Film

A’s News Clips, Tuesday, October 11, 2011 'Moneyball' bit player Korach likes film ... and Howe Ron Kantowski, Las Vegas Review Ken Korach's voice can be heard for about 22 seconds in the hit baseball movie "Moneyball," now showing at a theater near you. That's probably not enough to warrant an Oscar nomination, given Anthony Quinn holds the record for shortest amount of time spent on screen as a Best Supporting Actor of eight minutes, as painter Paul Gaugin in 1956's "Lust for Life." But whereas Brad Pitt only stars in "Moneyball," longtime Las Vegas resident Korach lived the 2002 season as play-by- play broadcaster for the Oakland Athletics, who set an American League record by winning 20 consecutive games. And though Korach's 45-minute interview about that season wound up on the cutting-room floor -- apparently along with photographs of the real Art Howe, the former A's manager who was nowhere near as rotund (or cantankerous) as Philip Seymour Hoffman made him out to be in the movie -- Korach said director Bennett Miller and the Hollywood people got it right. Except, perhaps, for the part about Art Howe. "I wish they had done a more flattering portrayal of Art ... but it's Hollywood," Korach said of "Moneyball," based on author Michael Lewis' 2003 book of the same name. "They wanted to show conflict between Billy and Art." Billy is Billy Beane, who was general manager of the Athletics then and still is today. Beane is credited with adapting the so-called "Moneyball" approach -- finding value in players based on sabermetric statistical data and analysis, rather than traditional scouting values such as hitting home runs and stealing bases -- to building a ballclub. -

October 3, 2017

October 3, 2017 Page 1 of 30 Clips (October 3, 2017) October 3, 2017 Page 2 of 30 Today’s Clips Contents FROM THE LOS ANGELES TIME (Page 3) Scioscia, set to return for 19th season as Angels manager, is optimistic it will be a good one Angels mailbag: Wrapping up the 2017 season FROM THE ORANGE COUNTY REGISTER (Page 7) Mike Scioscia OK returning to Angels for final year of his deal, with no extension now MLB's most popular jerseys revealed Son of former Angels pitcher Bert Blyleven tried to save people from Las Vegas shooter Angels 2017 season in review and roster outlook for 2018 FROM ANGELS.COM (Page 12) Scioscia 'thrilled' to return in '18, a contract year Angels fall short despite highlight-reel season Scioscia believes Pujols will bounce back in '18 Angels counting on healthier pitching staff in '18 FROM THE ASSOICATED PRESS (Page 18) Angels miss postseason again, yet optimism reigns in Anaheim FROM ESPN.COM (Page 20) Power Rankings: Indians eye bigger prize than regular-season No. 1 FROM SPORTING NEWS (Page 28) Angels' Justin Upton 'increasingly likely' to opt out of contract, report says FROM USA TODAY SPORTS (Page 29) 30 Hall of Famers Mike Trout surpassed in career WAR October 3, 2017 Page 3 of 30 FROM THE LOS ANGELES TIMES Scioscia, set to return for 19th season as Angels manager, is optimistic it will be a good one By Pedro Moura The longest-tenured head coach or manager in American professional sports will be back next year. Mike Scioscia said Monday that he would return in 2018 for his 19th season as Angels manager, his first as a lame duck since 2001. -

A's News Links, Tuesday, October 30, 2018 Baseball

A’S NEWS LINKS, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 30, 2018 BASEBALL RELATED ARTICLES MLB.COM A's sign Beane, Forst, Melvin to extensions by Daniel Kramer https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/as-sign-beane-forst-melvin-to-extensions/c-299930466 Half of Fielding Bible Award winners are first-timers by Daniel Kramer https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/2018-fielding-bible-awards-honor-first-timers/c-299949832 MLB announces roster for All-Star Tour in Japan by Staff https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/mlb-announces-roster-all-star-tour-in-japan/c-299919036 This is each club's biggest offseason need by Mark Feinsand https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/analyzing-each-clubs-biggest-offseason-need/c-299810886 Bolt hits third AFL triple in Monday's action by Staff https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/arizona-fall-league-roundup-for-october-29/c-299965090 Barrera to represent A's in Fall Stars Game by Jim Callis https://www.mlb.com/athletics/news/2018-fall-stars-game-rosters-led-by-vlad-jr/c-299924802 SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE A’s keep brain trust together, extend Billy Beane, David Forst, Bob Melvin by Susan Slusser & John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-keep-brain-trust-together-extend-Billy-13346932.php A’s Petit, Giants’ Meulens to tour Japan in All-Star series by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-Petit-Giants-Meulens-to-tour-Japan-in-13345211.php A’s Matt Chapman, Matt Olson win defensive awards by John Shea https://www.sfchronicle.com/athletics/article/A-s-Chapman-Olson-win-defensive-awards- 13345332.php MERCURY NEWS -

1999 100 Years of Panther Baseball

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Athletics Media Guides Athletics 1999 1999 100 Years of Panther Baseball University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1999 Athletics, University of Northern Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Northern Iowa, "1999 100 Years of Panther Baseball" (1999). Athletics Media Guides. 256. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg/256 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics Media Guides by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNI BASEBALL CELEBRATES 100 YEARS OF WINNING Dating back to 1893, no University of Northern Iowa athletic team has won more games than the Panther baseball program. This season, UNI baseball opens its lOOth season with 952 wins all-time. (No baseball team was fielded in 1903-04, 1909-10 and 1943-45.) Originally begun when the school was known as Iowa State Normal School, the baseball team has represented the school when it was also known as Iowa State Teachers College and the State College of Iowa before assuming its present title in 1967. Starting in the years with Captain Avery as coach of the first two squads, the Panthers have built a program that thrives on hard working young men dedicated to being the best they can be on the diamond and in the classroom. Last year was no exception, as five Panthers; Ryan McGuire, Kevin Briggeman, Greg Woodin, Scott Sobkowiak and Aaron Houdeshell were named academic all-MVC by the sports information directors of the league. -

Over 270 Alumni Have Passed from Recreation Ballpark to the Major

Over 270 alumni have passed from Recreation Ballpark to the Major Leagues since 1946, including Hall of Famer Kirby Puckett and Cy Young Award winners Barry Zito and Max Scherzer. Here's a full list: In total, 290 Visalia alumni have reached the Major Leagues (through the 2018 season): Bob Talbot, OF, Cubs, 1953-54 Doug Hansen, OF, Indians, 1951 Eddie Winceniak, SS, Cubs, 1956-57 Howie Goss, OF, Pirates, Colt 45s, 1962-63 Chuck Essegian, OF, Phillies, Cardinals, Indians, Angels, Royals, 1958-75 Marty Kutyna, P, Athletics, Senators, 1959-62 Vic Davalillo, OF, Indians, Cardinals, Pirates, Athletics, Dodgers, 1963-80 Vada Pinson - *NL-GG '61*, OF, Reds, Cardinals, Dodgers, Orioles, Indians, Athletics, 1958-75 Joe Gains, OF, Reds, Orioles, Astros, 1960-66 Jack Baldschun, P, Phillies, Reds, Padres, 1961-67, 1969-70 Ken Hunt, P, Reds, 1961 Johnny Edwards *NL-GG '63, '64*, C, Reds, Cardinals, Astros, 1961-74 Hiraldo (Chico) Ruiz, INF, Reds, Angels, 1964-71 Jack Aker, P, Athletics, Pilots, Yankees, Cubs, Braves, Mets, 1964-74 Ken Harrelson, 1B-OF, Athletics, Senators, Red Sox, Indians, 1963-71 John Wojcik, OF, Athletics, 1962-64 Larry Stahl, OF, Athletics, Mets, Padres, Reds, 1964-73 Bill Landis, P, Athletics, Red Sox, 1963, 1967-69 Jose Santiago, P, Athletics, Red Sox, 1963-70 Cisco Carlos, P, White Sox, Senators, 1967-70 Dick Kenworthy, INF, White Sox, 1962-68 Ken Berry, OF, White Sox, Brewers, Indians, 1962-75 Ernie McAnally, P, Mets, 1971-74 Bruce Boisclair, OF, Mets, 1974-79 Charlie Williams, P, Mets, Giants, 1971-78 Ken Singleton *RC '82*,