Identity Crime and Misuse in Australia 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Education Office GENERAL EMPLOYEE APPLICATION FORM

15 Johnson Street FORBES NSW 2871 Telephone: 02 6853 9300 www.wf.catholic.edu.au Catholic Education Office Diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes GENERAL EMPLOYEE APPLICATION FORM (PLEASE COMPLETE THIS FORM AND SUBMIT ORIGINAL TO PRINCIPAL/CEO) APPLICATIONS FOR PERMANENT AND TEMPORARY POSITIONS SHOULD BE SUPPORTED BY A LETTER ADDRESSING THE CRITERIA/POSITION REQUIREMENTS FOUND IN THE ADVERTISEMENT SECTION A – PERSONAL DETAILS Surname: Given Name/s: Title: Former Names: (if applicable): Date of Birth: Religion: Current Parish: Permanent Address: Postcode: Address For Correspondence: Postcode: Home phone: Work phone: Mobile: E-mail: Nationality: Australian Yes No If no, are you eligible to work in Australia ? ________________________________ Origin: Are you Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander? Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander Both I AM INTERESTED IN APPLYING FOR (tick all that apply): Classroom and Learning Support Services Administration Services Operational Services - Maintenance/Grounds Cleaner Permanent Full-time Part-time Casual Temporary COMPLETE BELOW ONLY IF APPLYING FOR PERMANENT/TEMPORARY POSITIONS: Position(s) applying for: Name of School: Address of School: I became aware of this position by: CEO Website Newspaper Other ___________________________ Refer to Employment Collection Notice – Annexure C “Faith Learning and Transformation in Jesus Christ” Version 1 SECTION B – EDUCATION EDUCATION: School(s) Attended Years of Attendance Certificate(s) Awarded OTHER QUALIFICATIONS: (including current incomplete courses): Name and Location of Institution Years of Attendance Award Conferred Date Conferred SECTION C – EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT (in reverse order from most recent employer – no further back than 15 years): Positions Held Reason for Resignation From To Name and Address of Employment or Termination Page 2 Version 1 SECTION D – WORKING WITH CHILDREN CHECK Teaching positions are child-related work, and legislation requires preferred applicants to be subject to a Working with Children Check (WWCC) for paid employees. -

NATIONAL POLICE CHECKING SERVICE (NPCS) APPLICATION/CONSENT FORM Risk Group Pty Ltd Individuals

NATIONAL POLICE CHECKING SERVICE (NPCS) APPLICATION/CONSENT FORM Risk Group Pty Ltd Individuals Please select appropriate box only: Reference No. Employee Contractor/Consultant Volunteer Other (Please specify) SECTION 1: PERSONAL INFORMATION - Use BLOCK LETTERS and black ink to complete this form. Mark checkboxes with an X. Names by which I am, or have been, known If more room is required, please list in the space provided at Section 6 on page 3 Family Name (Primary) First Name (Primary) Middle Names Aliases (Family Name first) Previous Names Maiden Name Birth Details Date of Birth Country State/Territory (dd/mm/yyyy) of Birth of Birth Suburb/Town Gender Male Female Unknown/Other of Birth Australian Licences Driver's Licence No. State/Territory Firearms Licence No. State/Territory Contact Details Phone Home ( ) Mobile Work ( ) Email Permanent Residential Address Over Last Five Years If more room is required, please list in the space provided at Section 6 on page 3. If full details of previous addresses are unavailable, details of town(s) and If actual dates are unavailable, details of state(s)/territory(ies) of residence will suffice. year of residence will suffice. CURRENT No./Street Period of Residence: Suburb P'code Year From State/ Country Territory PREVIOUS (IF APPLICABLE) No./Street Period of Residence: Suburb P'code Year From State/ Year To Territory Country PREVIOUS (IF APPLICABLE) No./Street Period of Residence: Suburb P'code Year From State/ Territory Country Year To Copyright ©2016 Risk Group Pty Ltd Individuals Form v3.0 All rights reserved Page 1 SECTION 2: PROOF OF IDENTITY (100-POINT CHECK) When applying for a national police history check you must provide proof of your identity with your application. -

Fahcsia Letterhead Template

Proof of Identity The Department may ask you to provide proof of your identity for the Business Services Wage Assessment Tool Scheme. To provide proof of your identity to the Department, you must provide Proof of Identity documents that meet the 100 point check. This is done by providing certified documents from the list on the attached pages. One of the documents from the list must contain a photograph. Together, these documents must, as a minimum, also provide evidence of your date of birth and signature. If your name used in one document is different from that shown on the other documents provided, evidence of the name change is also to be provided (for example, Marriage or Change of Name Certificate, or divorce papers issued by the Family Court). These documents DO NOT count towards the 100 points. Please do not send us your original documents. Certified copies must be signed by the appropriately qualified certifying person and they should also write the following information on the identity documents. “I certify this is a true and unaltered copy of the original” Name: Position: Date: Further information is available at Attachment B Certifying Documents. (Link) Document Explanation/Description Points Citizenship Certificate Australian citizenship certificate in your name/former 70 name. Australian Passport Current Australian passport in your name/former name. 70 (current) Australian Birth Original Australian birth certificate or birth extract in your 70 Certificate name/former name. Certificate of Evidence Certificate of Evidence of Residence Status (Form 283) 70 of Resident Status issued by the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, showing your name/former name. -

100 Points Guide 2 Documents

other requirements all customers As part of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter- Terrorism Financing Act (2006) all people who use our products and services, regardless of whether they have an account with NAB, need to present valid documentation to meet the 100 point identification requirements. is identification required by children? Children under 18 years of age also need two valid 100 points guide 2 documents . all you need to open an account what happens if I set up a new account on the internet or via telephone banking? We will set up your account as quickly as possible, however as required by law, we cannot allow drawings (debits) on your account until we sight the valid identification documents (original or certified copies) at your local branch. approved certifiers list For more information call Document copies must be certified by one of the following professions: 13 22 65 1 A licensed legal practitioner; 8am – 8pm EST Monday to Friday 2 A Justice of the Peace; or visit us at nab.com.au 3 A notary public (for the purposes of the Statutory Hearing impaired customers Declaration Regulations 1993); with telephone typewriters 4 A police officer; can contact us on 1300 363 647 5 An agent of the Australian Postal Corporation who is in charge of an office supplying postal services to the public; 6 A permanent employee of the Australian Postal Corporation with 2 or more years of continuous service who is employed in an office supplying postal services to the public; 7 An Australian consular officer or an Australian diplomatic officer -

National Police Checking Service (Npcs) Application/Consent Form (Accredited Agencies - Customers)

STAFF-IN-CONFIDENCE (WHEN COMPLETED) NATIONAL POLICE CHECKING SERVICE (NPCS) APPLICATION/CONSENT FORM (ACCREDITED AGENCIES - CUSTOMERS) SECTION 1: PERSONAL INFORMATION - Use BLOCK LETTERS and black ink to complete this form. Mark check boxes with an (X) Given Name Middle Name Surname Gender: gfedc Male gfedc Female gfedc Unknown/Other Date of Birth / / Place of Birth (Required) Suburb/Town State Country Current Residential Address (Required) Unit No. Street No. Street Postcode Suburb State Country Additional Details If more room is required, list on separate sheet, sign and send the sheet with this application form. Additional sheet included? gfedc Yes gfedc No Previous names (if applicable) Given Middle Name Name Surname Type: gfedc Maiden gfedc Previous gfedc Alias 5 Year Previous Address Unit No. Street No. Street Postcode Suburb State Country 5 Year Previous Address Unit No. Street No. Street Postcode Suburb State Country Contact Details Phone Private Business Mobile Email Documents Aust. Driver's Licence No. State/Territory Firearms Licence No. State/Territory Passport No. Passport Country Passport Type gfedc Private gfedc Government gfedc UN Refugee Version 2.1 STAFF-IN-CONFIDENCE (WHEN COMPLETED) NATIONAL POLICE CHECKING SERVICE (NPCS) APPLICATION/CONSENT FORM (ACCREDITED AGENCIES - CUSTOMERS) SECTION 2: PROOF OF IDENTITY (100 - POINT CHECK) When applying for a national police history check you must provide proof of your identity with your application. You will be asked to provide personal identity documents that add up to at least 100 points. The combination of documents supplied should, as a minimum, evidence your full name and date of birth. All documents must be originals or certified true copies. -

Evidence of Identity for Documentary Declarations

EVIDENCE OF IDENTITY FOR DOCUMENTARY (PAPER) TRANSACTIONS (Effective 20 April 2007) Since the introduction of Integrated Cargo System (ICS) functionality, importers and exporters have been required to provide evidence of identity (EOI) when lodging documentary transactions with Customs. The EOI procedures for imports and exports have been the same, however these procedures and requirements have changed. The main procedural difference has been the use of authorised Australia Post outlets to conduct EOI on behalf of Customs for exports transactions. This did not apply to imports transactions. From 20 April 2007, Australia Post will no longer have a role in conducting EOI checks for documentary export transactions. From that date, procedures for exports and imports will be identical, reflecting the current imports processes outlined below. EOI PROCEDURES - IMPORTS AND EXPORTS Generally, Customs will not accept faxed or mailed import or export documentary transactions. The exceptions for faxing or mailing documentary transactions are: Clients located in rural or remote areas Under the following conditions, clients must ensure that: • Faxed or mailed documents must have supporting (photocopied) evidence of identity (EOI) documents attached, as per requirements specified below; and • Documents must be faxed or mailed to the contact details specified at Table 3. Clients that import or export cargo through Australia Post mail Documentary transactions may be presented at any Customs counter. Clients are required to undergo an EOI check each time they present Customs-related documentary transactions at Customs counters. WHAT IS EOI? EOI is a verification process that individuals and businesses are required to undertake to prove who they are. All electronic users of the ICS are required to undergo an EOI check when applying for a digital certificate. -

Hot Chocolate @ Max Brenner Phillips Island Mt. Buller

Queen Victoria Market – Hot Chocolate @ Max Brenner Phillips Island Mt. Buller – Sightseers $56 Family – Snow tubing free, tobogganing free Federation Square Children’s Playground Collingwood Childrens Farm – Farmers Market 14th August Shopping There are four main shopping areas in the city of Melbourne. Bourke St mall, which is where the major department stores are, Melbourne Central and QV (NOT the Queen Victoria market), which are both located on La Trobe St, and Spencer St shopping center (the old DFO). DFO – Authentic Converse Factory Outlet Melbourne - Chocolate Shops Haighs Block Arcade, Lind't, (Collins street), Koko Black ( Royal Arcade or Upper Collins st), Max Brenner (QV Centre), San Churro (QV Centre), The Chokolait Hub (Hub arcade just off Royal Arcade). SIM cards for phones are very easy to buy- they usually cost aorund AUD$20 or $30 dollars and come with a credit (usually aorund $5 or $10) towards phone calls. Most calls are time charged and charged by either the second or 30 seconds. 3 largest companies are; Telstra, Optus and Vodafone. Mobile phone shops (which breed like rabbits) or department/discopunt stores are your best bets to purchase these as they usually have a range. The Post Office also retail them. SURBURBS TO LIVE Doncaster and Balwyn Hawthorn and Kew as you mentioned, Ivanhoe, Alphington, Fairfield, Northcote, Brunswick, Essendon, Strathmore, Ascot Vale, Moonee Ponds. In regards to schools one area to consider in the Eastern suburbs is Balwyn. Little bit further out than Kew or Hawthorn but very nice area and a resonable tram ride to the city. The local secondary there has a great reputation and many people compare it a private school without the fees. -

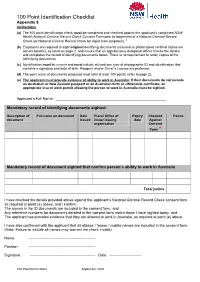

100 Point Identification Checklist

100 Point Identification Checklist Appendix 8 Instructions (a) The 100 point identification check must be completed and checked against the applicant’s completed NSW Health National Criminal Record Check Consent Form prior to lodgement of a National Criminal Record Check (or National Criminal Record Check for Aged Care purposes). * (b) Employers are required to sight original identifying documents (scanned or photocopied certified copies are not acceptable), as listed on page 2, and ensure that an appropriately delegated officer checks the details and completes the record of identifying documents below. There is no requirement to retain copies of the identifying documents. (c) Identification must be current and must include at least one type of photographic ID and identification that contains a signature and date of birth. Passport and/or Driver’s License are preferred. (d) The point score of documents produced must total at least 100 points (refer to page 2). (e) The applicant must provide evidence of ability to work in Australia: If their documents do not include an Australian or New Zealand passport or an Australian birth or citizenship certificate, an appropriate visa or work permit allowing the person to work in Australia must be sighted. Applicant’s Full Name: ______________________________________________________ Mandatory record of identifying documents sighted: Description of Full name on document Date Place/ Office of Expiry Checked Points document issued issue/ issuing date Against organisation Consent Form * Mandatory record of document sighted that confirm person’s ability to work in Australia Total points I have checked the details provided above against the applicant’s National Criminal Record Check consent form as required at point (a) above, and I confirm: The names in the ID documents are included in the consent form, and Any reference numbers for documents detailed in the consent form match those I have sighted today, and The applicant has provided evidence that they are allowed to work in Australia, as required at point (e) above. -

100 Point Identification Check Instructions: 1

100 Point Identification Check Instructions: 1. The 100 point identification check must be completed and lodged with the completed application to the NSW Ministry of Health Central Register. 2. Certified copies only of documents should be provided to satisfy the 100 point check. Do not provide original documents. 3. Identification must be current and should include at least one type of photographic ID and identification that contains a signature and date of birth. 4. The point score of the documents produced must total at least 100 points. Applicant’s name: ________________________________________________________________ DOCUMENTS POINTS Primary documents 70 Birth Certificate Birth card issued by the NSW Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages Citizenship Certificate Current Australia Passport Expired Australian Passport which has not been cancelled and was current within the preceding two years Current passport from another country or diplomatic documents Secondary documents – must have a photograph and a name. The first item from 40 this list is worth 40 points. Any additional items used are worth only 25 points each Current driver photo licence issued by an Australia state of territory Identification card issued to a public employee Identification card issued by the Australian or any state government as evidence of a person’s entitlement to a financial benefit Identification card issued to a student at a tertiary education institution Document – must have name and address 35 Document held by a cash dealer giving security -

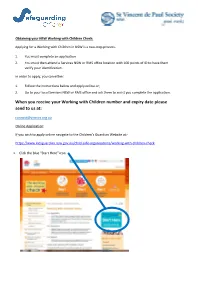

When You Receive Your Working with Children Number and Expiry Date Please Send to Us At

Obtaining your NSW Working with Children Check: Applying for a Working with Children in NSW is a two-step process- 1. You must complete an application 2. You must then attend a Services NSW or RMS office location with 100 points of ID to have them verify your identification. in order to apply, you can either: 1. Follow the instructions below and apply online or; 2. Go to your local Services NSW or RMS office and ask them to assist you complete the application. When you receive your Working with Children number and expiry date please send to us at: [email protected] Online Application: If you wish to apply online navigate to the Children’s Guardian Website at:- https://www.kidsguardian.nsw.gov.au/child-safe-organisations/working-with-children-check 1. Click the blue “Start Here” icon 2. Select “Apply for your Check” 3. Complete your personal details. Under ‘Purpose for Check’ – choose ‘Volunteer’ Under Child-related sector* - choose ‘Clubs or other bodies that provide services to children’ 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 4 . Confirm your consent & submit. 5. You will then receive an application number. Click on the Print Summary button & print out take the summary with you to Services NSW with 100 points of ID to be identified. WHEN YOU HAVE YOUR NUMBER AND EXPIRY DATE PLEASE SEND IT TO US AT: [email protected] RELEVANT PROOF OF IDENTITY DOCUMENTS You must provide proof of your identity documents with this form that are greater than or equal to 100 points of identity, as listed below. -

Fraud Report FINAL 23/12/03 3:25 PM Page I

Fraud Report FINAL 23/12/03 3:25 PM Page i M E I A N L T R O A F P V I I A C T O R PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA DRUGS AND CRIME PREVENTION COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO FRAUD AND ELECTRONIC COMMERCE Final Report January 2004 by Authority Government Printer for the State of Victoria No. 55 Session 2003-2004 Fraud Report FINAL 23/12/03 3:25 PM Page ii The Report was prepared by the Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee. Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee Inquiry into Fraud and Electronic Commerce: – Final Report DCPC, Parliament of Victoria ISBN: 0-646-43091-2 Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee Level 8 35 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Telephone: (03) 9651 3541 Facsimile: (03) 9651 3603 Email: [email protected] http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/dcpc page ii Fraud Report FINAL 23/12/03 3:25 PM Page iii Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee – 55th Parliament Ms Carolyn Hirsh, M.L.C.– Chair The Hon. Robin Cooper, M.L.A. – Deputy Chairman Ms Kirstie Marshall, M.L.A. Mr Ian Maxfield, M.L.A. The Hon. Sang Minh Nguyen, M.L.C. Dr Bill Sykes, M.L.A. Mr Kim Wells, M.L.A. Drugs and Crime Prevention Committee – 54th Parliament The Hon. Cameron Boardman, M.L.C. – Chairman Mr Bruce Mildenhall, M.L.A. – Deputy Chairman The Hon. Robin Cooper, M.L.A. Mr Kenneth Jasper, M.L.A. Mr Hurtle Lupton, M.L.A. The Hon. Sang Minh Nguyen, M.L.C. -

Procedure Template

BUSINESS RULES MANUAL FOR THE CONTRACTING RAIL SAFETY WORKER L0-HMR-MAN-001 Version: 4 Effective from: 13th September 2013 Approval Amendment Record Approval Date Version Description 26/04/2012 1 Initial issue under Metro 01/03/2013 2 Update to cover all RSW roles Inclusion of Minors to the Around the Track Person role, changes to the recognition of overseas engineering 30/08/2013 3 degrees, updates to health assessments and minor amendments. 13/09/2013 4 Clarification on Drug and Alcohol Screening Approving Manager: GM HSEQ Approval Date: 13/09/2013 Next Review Date: 13/09/2015 PRINTOUT MAY NOT BE UP-TO-DATE; REFER TO METRO INTRANET FOR THE LATEST VERSION Page 1 of 41 BUSINESS RULES MANUAL FOR THE CONTRACTING RAIL SAFETY WORKER L0-HMR-MAN-001 Version: 4 Effective from: 13th September 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................6 1.1 Purpose............................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Scope.................................................................................................................. 6 1.3 Definitions and Responsibilities........................................................................... 6 1.4 Responsibilities ................................................................................................... 9 1.5 Reference Documents......................................................................................... 9 2. Application Process