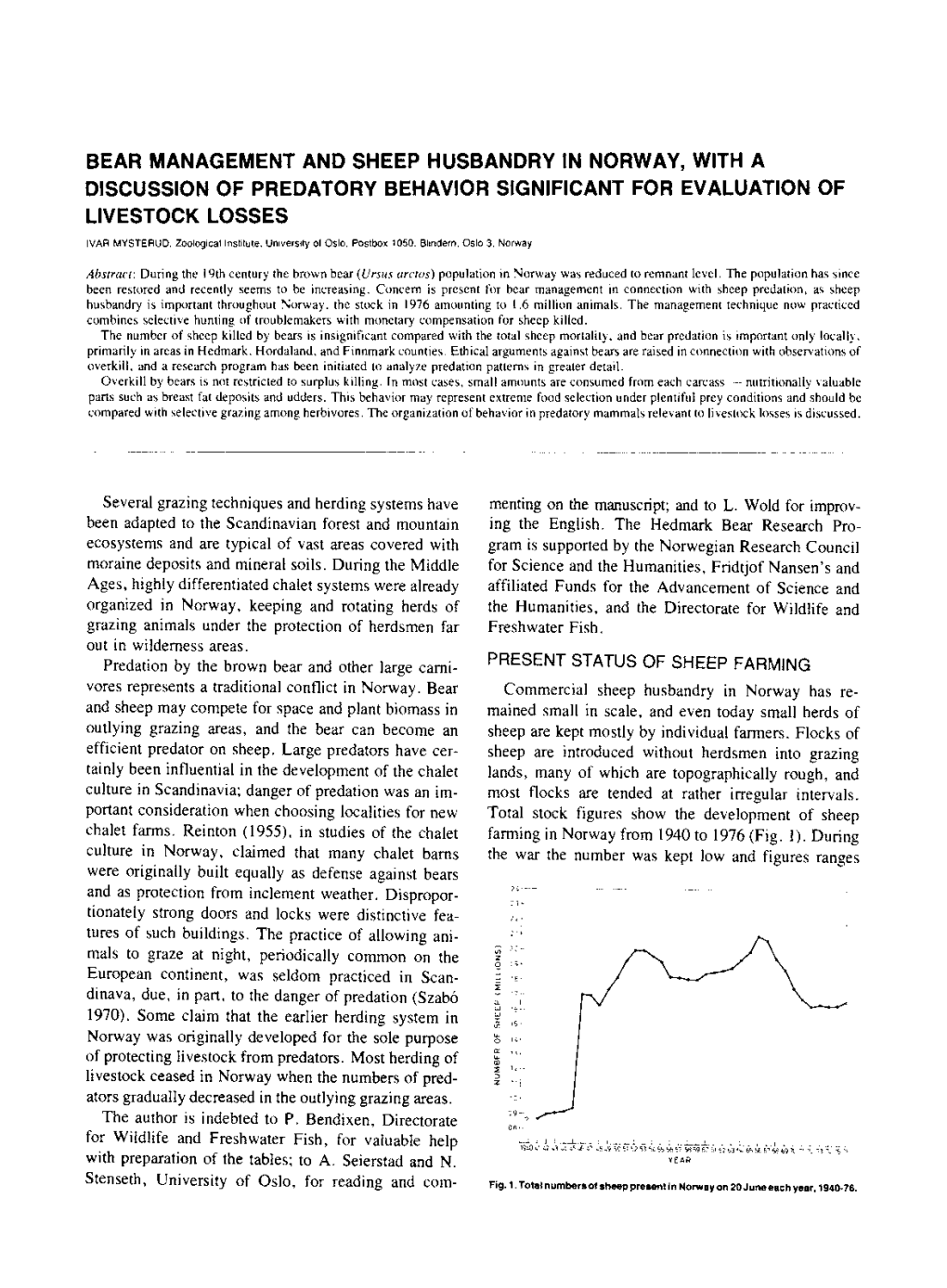

Bear Management and Sheep Husbandry in Norway, with a Discussion of Predatory Behavior Significant for Evaluation of Livestock Losses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vulpes Vulpes) Evolved Throughout History?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses Environmental Studies Program 2020 TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? Abigail Misfeldt University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Disclaimer: The following thesis was produced in the Environmental Studies Program as a student senior capstone project. Misfeldt, Abigail, "TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY?" (2020). Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses. 283. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/envstudtheses/283 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Undergraduate Student Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TO WHAT EXTENT HAS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMANS AND RED FOXES (VULPES VULPES) EVOLVED THROUGHOUT HISTORY? By Abigail Misfeldt A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The University of Nebraska-Lincoln In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Science Major: Environmental Studies Under the Supervision of Dr. David Gosselin Lincoln, Nebraska November 2020 Abstract Red foxes are one of the few creatures able to adapt to living alongside humans as we have evolved. All humans and wildlife have some id of relationship, be it a friendly one or one of mutual hatred, or simply a neutral one. Through a systematic research review of legends, books, and journal articles, I mapped how humans and foxes have evolved together. -

Selective Consumption of Sockeye Salmon by Brown Bears: Patterns of Partial Consumption, Scavenging, and Implications for Fisheries Management

Selective consumption of sockeye salmon by brown bears: patterns of partial consumption, scavenging, and implications for fisheries management Alexandra E. Lincoln A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2019 Committee: Thomas P. Quinn Aaron J. Wirsing Ray Hilborn Trevor A. Branch Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences University of Washington ©Copyright 2019 Alexandra E. Lincoln University of Washington Abstract Selective consumption of sockeye salmon by brown bears: patterns of partial consumption, scavenging, and implications for fisheries management Alexandra E. Lincoln Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Thomas P. Quinn School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences Animal foraging requires a series of complex decisions that ultimately end with consumption of resources. The extent of consumption varies among consumers, including predator-prey systems; some predators always completely consume their prey but others may partially consume prey that are too large to be completely consumed, or consume only parts of smaller prey and discard the remains. Partial consumption of prey may allow predators to maximize energy intake through selectively feeding on energy-rich tissue, as is observed in bears (Ursus spp.) selectively feeding on Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.). Here, we examined selective and partial consumption of sockeye salmon (O. nerka) by brown bears (U. arctos) in western Alaska. First, we tested a series of hypotheses to determine what factors best explain why some salmon are killed and abandoned without tissue consumption, and what tissues are consumed from the salmon that are fed upon. We found that a foraging strategy consistent with energy maximization best explained patterns of selective prey discard and partial consumption, as traits of the fish itself (size, sex, and condition) and the broader foraging opportunities (availability of salmon as prey) were important. -

Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’S Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Proceedings for 4-1-2007 MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE Judith C. Webster Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Webster, Judith C., "MISSING CATS, STRAY COYOTES: ONE CITIZEN’S PERSPECTIVE" (2007). Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings. 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Missing Cats, Stray Coyotes: One Citizen’s Perspective * Judith C. Webster , Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Abstract : The author explores the issue of urban coyotes and coyote management from a cat owner’s perspective, with specific examples from Vancouver, B.C., Canada. Following a personal encounter with two coyotes in July 2005 that led to the death of a cat, the author has delved into the history of Vancouver’s “Co-existing with Coyotes”, a government-funded program run by a non- profit ecological society. The policy’s roots in conservation biology, the environmental movement, and the human dimensions branch of wildlife management are documented. The author contends that “Co-existing with Coyotes” puts people and pets at greater risk of attack by its inadequate response to habituated coyotes, and by an educational component that misrepresents real dangers and offers unworkable advice. -

Comparative Patterns of Predation by Cougars and Recolonizing Wolves in Montana’S Madison Range

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service May 2007 Comparative Patterns of Predation by Cougars and Recolonizing Wolves in Montana’s Madison Range Todd C. Atwood Utah State University, Logan, UT Eric M. Gese USDA/APHIS/WS National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Kyran E. Kunkel Utah State University, Logan, UT Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Atwood, Todd C.; Gese, Eric M.; and Kunkel, Kyran E., "Comparative Patterns of Predation by Cougars and Recolonizing Wolves in Montana’s Madison Range" (2007). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 696. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/696 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Research Article Comparative Patterns of Predation by Cougars and Recolonizing Wolves in Montana’s Madison Range TODD C. ATWOOD,1,2 Department of Wildland Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA ERIC M. GESE, United States Department of Agriculture–Animal Plant Health Inspection Service–Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center, Department of Wildland Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA KYRAN E. KUNKEL, Department of Wildland Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA ABSTRACT Numerous studies have documented how prey may use antipredator strategies to reduce the risk of predation from a single predator. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet: The Impact of Tibetan Brown Bears and Other Wildlife on Nomadic Herders Dawa Tsering, John Farrington, and Kelsang Norbu August 2006 WWF China – Tibet Program Author Contact Information: Dawa Tsering, Tibet Academy of Social Sciences and WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] (+86)(891) 636-4380 John D. Farrington Tibet University 36 Jiangsu Road Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] [email protected] Kelsang Norbu WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet Abstract The multiple-use Chang Tang and Seling Lake Nature Reserves were created in 1993 to protect the unique assemblage of large fauna inhabiting the high-altitude steppe grasslands of northern Tibet, including the Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild ass, Tibetan brown bear, Tibetan Gazelle, wild yak, and snow leopard. Prior to creation of the reserve, many of these species were heavily hunted for meat and sale of parts. Since creation of the reserve, however, killing of wildlife by subsistence hunters and commercial poachers has declined while in the past five years a new problem has emerged, that of human-wildlife conflict. With human, livestock, and wildlife populations in the reserves all increasing, and animals apparently emboldened by reserve-wide hunting bans, all forms of human-wildlife conflict have surged rapidly since 2001. -

“Reversed” Intraguild Predation: Red Fox Cubs Killed by Pine Marten

Acta Theriol (2014) 59:473–477 DOI 10.1007/s13364-014-0179-8 SHORT COMMUNICATION “Reversed” intraguild predation: red fox cubs killed by pine marten Marcin Brzeziński & Łukasz Rodak & Andrzej Zalewski Received: 31 January 2014 /Accepted: 27 February 2014 /Published online: 27 March 2014 # Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Białowieża, Poland 2014 Abstract Camera traps deployed at a badger Meles meles set species (e.g. mesopredators) are also affected by interactions in mixed pine forest in north-eastern Poland recorded inter- with high rank species (top predators). Top predators may specific killing of red fox Vulpes vulpes cubs by pine marten limit mesopredator density by reducing access to food (ex- Martes martes. The vixen and her cubs settled in the set at the ploitation competition) or by direct interactions (interference beginning of May 2013, and it was abandoned by the badgers competition), of which interspecific killing (intraguild preda- shortly afterwards. Five fox cubs were recorded playing in tion) is the most extreme (Sinclair et al. 2006). Intraguild front of the den each night. Ten days after the first recording of predation is frequently observed interaction among predators the foxes, a pine marten was filmed at the set; it arrived in the (Polis et al. 1989; Arim and Marquet 2004), and highly morning, made a reconnaissance and returned at night when asymmetric interspecific killing is usually mediated by a the vixen was away from the set. The pine marten entered the predator of larger body size that is able to kill smaller ones den several times and killed at least two fox cubs. -

Suspected Surplus Killing of Harbor Seal Pups by Killer Whales

150 NORTHWESTERN NATURALIST 86(3) SOWLS AL, DEGANGE AR, NELSON JW, LESTER GS. com (PJC); Carter Biological Consulting, 1015 1980. Catalog of California seabird colonies. Hampshire Road, Victoria, British Columbia V8S Washington, DC: US Fish and Wildlife Service, 4S8 Canada (HRC); US Fish and Wildlife Service, Biological Services Program, FWS/OBS-78/78. San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Com- 253 p. plex, PO Box 524, Newark, California 94560 USA TAKEKAWA JE, CARTER HR, HARVEY TE. 1990. De- cline of the common murre in central California, (GJM, MWP); Present Address (MWP): US Fish 1980±1986. In: SG Sealy, editor. Auks at sea. Stud- and Wildlife Service, Red Rock Lakes National ies in Avian Biology 14:149±163. Wildlife Refuge, 27820 South Centennial Road, Lima, Montana 59739 USA. Submitted 9 March Department of Wildlife, Humboldt State University, 2005, accepted 27 July 2005. Corresponding Editor: Arcata, California 95521 USA; philpcapitolo@hotmail. CJ Ralph. NORTHWESTERN NATURALIST 86:150±154 WINTER 2005 SUSPECTED SURPLUS KILLING OF HARBOR SEAL PUPS (PHOCA VITULINA) BY KILLER WHALES (ORCINUS ORCA) JOSEPH KGAYDOS,STEPHEN RAVERTY,ROBIN WBAIRD, AND RICHARD WOSBORNE Key words: harbor seal, killer whale, Orci- novel mortality pattern in harbor seals (Phoca nus orca, Phoca vitulina, surplus killing, preda- vitulina) that strongly suggests 1 or more in- tion, disease, San Juan Islands, Washington dividuals from 1 of these ecotypes killed seal pups for reasons other than consumption. Within the inland waters of Washington State As part of an ongoing disease-screening pro- and southern British Columbia Province, 3 dis- ject, complete postmortem examinations were tinct ecotypes of killer whales (Orcinus orca) oc- performed on dead marine mammals in suit- cur. -

Wolf-Prey Relations L

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for 2003 Wolf-Prey Relations L. David Mech USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Rolf O. Peterson Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Mech, L. David and Peterson, Rolf O., "Wolf-Prey Relations" (2003). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 321. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/321 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 5 Wolf-Prey Relations L. David Mech and Rolf 0. Peterson AS 1 (L. o. MECH) watched from a small ski plane while experience, and vigor of adults. Prey populations sustain fifteen wolves surrounded a moose on snowy Isle Roy themselves by the reproduction and survival of their vig ale, I had no idea this encounter would typify observa orous members. Wolves coexist with their prey by ex tions I would make during 40 more years of studying ploiting the less fit individuals. This means that most wolf-prey interactions. hunts by wolves are unsuccessful, that wolves must travel My usual routine while observing wolves hunting was widely to scan the herds for vulnerable individuals, and to have my pilot keep circling broadly over the scene so that these carnivores must tolerate a feast-or-famine ex I could watch the wolves' attacks without disturbing istence (see Peterson and Ciucci, chap. -

Predator Size and Prey Size–Gut Capacity Ratios Determine Kill

Predator size and prey size–gut capacity ratios determine kill frequency and carcass production in terrestrial carnivorous mammals Annelies De Cuype1, Marcus Clauss2, Chris Carbone3, Daryl Codron4,5, An Cools1, Myriam Hesta1 and Geert P. J. Janssens1 1Laboratory of Animal Nutrition, Dept of Nutrition, Genetics and Ethology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent Univ., Heidestraat 19, BE-9820 Merelbeke, Belgium 2Clinic for Zoo Animals, Exotic Pets and Wildlife, Univ. of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland 3Inst. of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, UK 4Inst. für Geowissenschaften, AG für Angewandte und Analytische Paläontologie, Johannes Gutenberg- Univ. Mainz, Mainz, Germany 5Florisbad Quaternary Research Dept, National Museum, Bloemfontein, South Africa Corresponding author: Annelies De Cuype, Laboratory of Animal Nutrition, Dept of Nutrition, Genetics and Ethology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent Univ., Heidestraat 19, BE-9820 Merelbeke, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Decision date: 19-Jul-2018 This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: [10.1111/oik.05488]. Accepted Article Accepted ‘This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.’ Abstract Carnivore kill frequency is a fundamental part of predator–prey interactions, which are important shapers of ecosystems. Current field kill frequency data are rare and existing models are insufficiently adapted to carnivore functional groups. We developed a kill frequency model accounting for carnivore mass, prey mass, pack size, partial consumption of prey and carnivore gut capacity. Two main carnivore functional groups, small prey-feeders versus large prey-feeders, were established based on the relationship between stomach capacity (C) and pack corrected prey mass (iMprey). -

WITMER.CHP:Corel VENTURA

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Carnivore Conservation Forest Service Pacific Northwest and Management in the Interior Research Station United States Columbia Basin: Issues and Department of the Interior Environmental Correlates Bureau of Land Management Gary W. Witmer, Sandra K. Martin, and Rodney D. Sayler General Technical Report PNW-GTR-420 July 1998 Authors GARY W. WITMER is a wildlife research biologist, USDA/APHIS National Wildlife Research Center, 1716 Heath Parkway, Fort Collins, CO 80524-2719; and SANDRA K. MARTIN is an adjunct wildlife faculty and RODNEY D. SAYLER is an associate professor of wildlife, Washington State University, Department of Natural Resource Sciences, Pullman, WA 99164-6410. This document is published by the Pacific Northwest Research Station under agreement no. 95-06-54-18. Forest Carnivore Conservation and Management in the Interior Columbia Basin: Issues and Environmental Correlates Gary W. Witmer, Sandra K. Martin, and Rodney D. Sayler Interior Columbia Basin Ecosytem Management Project: Scientific Assessment Thomas M. Quigley, Editor U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-420 July 1998 Abstract Witmer, Gary W.; Martin, Sandra K.; Sayler, Rodney D. 1998. Forest carnivore conservation and management in the interior Columbia basin: issues and environmental correlates. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-420. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 51 p. (Quigley, Thomas M., ed.; Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project: scientific assessment). Forest carnivores in the Pacific Northwest include 11 medium to large-sized mammalian species of canids, felids, mustelids, and ursids. These carnivores have widely differing status in the region, with some harvested in regulated furbearer seasons, some taken for depredations, and some protected because of rarity. -

The Causes and Consequences of Partial Prey Consumption by Wolves Preying on Moose

Behav Ecol Sociobiol (2012) 66:295–303 DOI 10.1007/s00265-011-1277-0 ORIGINAL PAPER The causes and consequences of partial prey consumption by wolves preying on moose John A. Vucetich & Leah M. Vucetich & Rolf O. Peterson Received: 20 July 2011 /Revised: 7 October 2011 /Accepted: 8 October 2011 /Published online: 27 October 2011 # Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract For a wide range of taxa, partial prey consumption (Conover 1966), spiders (Pollard 1989;Samu1993), (PPC) is a frequent occurrence. PPC may arise from predaceous mites (Metz et al. 1988), insects (Johnson et physiological constraints to gut capacity or digestive rate. al. 1975; Loiterton and Magrath 1996), shrews (Haberl Alternatively, PPC may represent an optimal foraging 1998), weasels (Ehrlinge et al. 1974; Oksanen et al. 1985), strategy. Assessments that clearly distinguish between these marsupials (Chen et al. 2004), canids (Patterson 1994), and causes are rare and have been conducted only for invertebrate bears (Reynolds et al. 2002). Analogous behaviors have species that are ambush predators with extra-intestinal even been described for modern humans living in western digestion (e.g., wolf spiders). We present the first strong test societies (Rathje 1984; Gillisa et al. 1995). Despite being for the cause of PPC in a cursorial vertebrate predator with commonplace and despite continued interest to document intestinal digestion: wolves (Canis lupus) feeding on moose and describe partial prey consumption (PPC), the causes (Alces alces). Previous theoretical assessments indicate that and consequences of PPC are not well understood. if PPC represents an optimal foraging strategy and is not PPC is predicted by three different hypotheses. -

Some Observations on the Diet of the Spotted Hyaena (Crocuta Crocuta) Using Scats Analysis

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-4, 2017 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Some Observations on the Diet of the Spotted Hyaena (Crocuta Crocuta) Using Scats Analysis Levi Ndubuisi ONYENWEAKU Department Of Forestry And Environmental Management, Michael Okpara University Of Agriculture, Umudike, Abia State Abstract: The diet of the spotted hyaenas (Crocuta considerable distance (Mills, 1984). Their olfactory crocuta) was studied using a non-invasive senses are well developed for locating carrion technique: scats analysis. 54 scat samples were while auditory senses help individuals to locate collected from Madikwe Game Reserve, South where others are already feeding (Mills, 1978; Africa and analysed. A total of 10 food items were Holekamp et al., 2007a, b; Burgener et al., 2009). isolated from the samples and 9 wildlife species Carrion are always consumed quickly and food is were identified as prey. It was found that spotted rarely stored or taken back to the dens (Kruuk, hyaenas consumed mainly large mammals in their 1972; Mills, 1984). Their territory sizes vary, and diets. Impala (Aepyceros melampus), warthog may be determined by the pattern of dispersion of (Phacochoerus africanus) and wildebeest food within the territory (Frank 1986; Tilson and (Connochaetes taurinus) were the most consumed Henschel, 1986; Hofer and East, 1993). prey species, having occurrence frequency of Dietary scat analysis has proven to be one of the 16.67%, 11.11% and 9.26% respectively. This most effective techniques used in studying the diet study suggests that the use of scats in identifying of carnivores (Mills, 1992). Scientific studies have the food components of carnivore species and their tried to analyse the diets and feeding ecology of diet analysis could be helpful in the management of mesocarnivores directly by observation and wild species.