L10N Intro to HTML

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Find the Best Hashtags for Your Business Hashtags Are a Simple Way to Boost Your Traffic and Target Specific Online Communities

CHECKLIST How to find the best hashtags for your business Hashtags are a simple way to boost your traffic and target specific online communities. This checklist will show you everything you need to know— from the best research tools to tactics for each social media network. What is a hashtag? A hashtag is keyword or phrase (without spaces) that contains the # symbol. Marketers tend to use hashtags to either join a conversation around a particular topic (such as #veganhealthchat) or create a branded community (such as Herschel’s #WellTravelled). HOW TO FIND THE BEST HASHTAGS FOR YOUR BUSINESS 1 WAYS TO USE 3 HASHTAGS 1. Find a specific audience Need to reach lawyers interested in tech? Or music lovers chatting about their favorite stereo gear? Hashtags are a simple way to find and reach niche audiences. 2. Ride a trend From discovering soon-to-be viral videos to inspiring social movements, hashtags can quickly connect your brand to new customers. Use hashtags to discover trending cultural moments. 3. Track results It’s easy to monitor hashtags across multiple social channels. From live events to new brand campaigns, hashtags both boost engagement and simplify your reporting. HOW TO FIND THE BEST HASHTAGS FOR YOUR BUSINESS 2 HOW HASHTAGS WORK ON EACH SOCIAL NETWORK Twitter Hashtags are an essential way to categorize content on Twitter. Users will often follow and discover new brands via hashtags. Try to limit to two or three. Instagram Hashtags are used to build communities and help users find topics they care about. For example, the popular NYC designer Jessica Walsh hosts a weekly Q&A session tagged #jessicasamamondays. -

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: a Review and Framework

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework Item Type Journal Article (On-line/Unpaginated) Authors Trant, Jennifer Citation Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework 2009-01, 10(1) Journal of Digital Information Journal Journal of Digital Information Download date 02/10/2021 03:25:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105375 Trant, Jennifer (2009) Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework. Journal of Digital Information 10(1). Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework J. Trant, University of Toronto / Archives & Museum Informatics 158 Lee Ave, Toronto, ON Canada M4E 2P3 jtrant [at] archimuse.com Abstract This paper reviews research into social tagging and folksonomy (as reflected in about 180 sources published through December 2007). Methods of researching the contribution of social tagging and folksonomy are described, and outstanding research questions are presented. This is a new area of research, where theoretical perspectives and relevant research methods are only now being defined. This paper provides a framework for the study of folksonomy, tagging and social tagging systems. Three broad approaches are identified, focusing first, on the folksonomy itself (and the role of tags in indexing and retrieval); secondly, on tagging (and the behaviour of users); and thirdly, on the nature of social tagging systems (as socio-technical frameworks). Keywords: Social tagging, folksonomy, tagging, literature review, research review 1. Introduction User-generated keywords – tags – have been suggested as a lightweight way of enhancing descriptions of on-line information resources, and improving their access through broader indexing. “Social Tagging” refers to the practice of publicly labeling or categorizing resources in a shared, on-line environment. -

HTML5 Favorite Twitter Searches App Browser-Based Mobile Apps with HTML5, CSS3, Javascript and Web Storage

Androidfp_19.fm Page 1 Friday, May 18, 2012 10:32 AM 19 HTML5 Favorite Twitter Searches App Browser-Based Mobile Apps with HTML5, CSS3, JavaScript and Web Storage Objectives In this chapter you’ll: ■ Implement a web-based version of the Favorite Twitter Searches app from Chapter 5. ■ Use HTML5 and CSS3 to implement the interface of a web app. ■ Use JavaScript to implement the logic of a web app. ■ Use HTML5’s Web Storage APIs to store key-value pairs of data that persist between executions of a web app. ■ Use a CSS reset to remove all browser specific HTML- element formatting before styling an HTML document’s elements. ■ Save a shortcut for a web app to your device’s home screen so you can easily launch a web app. = DRAFT: © Copyright 1992–2012 by Deitel & Associates, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Androidfp_19.fm Page 2 Friday, May 18, 2012 10:32 AM 2 Chapter 19 HTML5 Favorite Twitter Searches App 19.1 Introduction 19.5 Building the App 19.2 Test-Driving the Favorite Twitter 19.5.1 HTML5 Document Searches App 19.5.2 CSS 19.5.3 JavaScript 19.3 Technologies Overview Outline 19.6 Wrap-Up 19.1 Introduction The Favorite Twitter Searches app from Chapter 5 allowed users to save their favorite Twit- ter search strings with easy-to-remember, user-chosen, short tag names. Users could then conveniently follow tweets on their favorite topics. In this chapter, we reimplement the Fa- vorite Twitter Searches app as a web app, using HTML5, CSS3 and JavaScript. -

Copyrighted Material

05_096970 ch01.qxp 4/20/07 11:27 PM Page 3 1 Introducing Cascading Style Sheets Cascading style sheets is a language intended to simplify website design and development. Put simply, CSS handles the look and feel of a web page. With CSS, you can control the color of text, the style of fonts, the spacing between paragraphs, how columns are sized and laid out, what back- ground images or colors are used, as well as a variety of other visual effects. CSS was created in language that is easy to learn and understand, but it provides powerful control over the presentation of a document. Most commonly, CSS is combined with the markup languages HTML or XHTML. These markup languages contain the actual text you see in a web page — the hyperlinks, paragraphs, headings, lists, and tables — and are the glue of a web docu- ment. They contain the web page’s data, as well as the CSS document that contains information about what the web page should look like, and JavaScript, which is another language that pro- vides dynamic and interactive functionality. HTML and XHTML are very similar languages. In fact, for the majority of documents today, they are pretty much identical, although XHTML has some strict requirements about the type of syntax used. I discuss the differences between these two languages in detail in Chapter 2, and I also pro- vide a few simple examples of what each language looks like and how CSS comes together with the language to create a web page. In this chapter, however, I discuss the following: ❑ The W3C, an organization that plans and makes recommendations for how the web should functionCOPYRIGHTED and evolve MATERIAL ❑ How Internet documents work, where they come from, and how the browser displays them ❑ An abridged history of the Internet ❑ Why CSS was a desperately needed solution ❑ The advantages of using CSS 05_096970 ch01.qxp 4/20/07 11:27 PM Page 4 Part I: The Basics The next section takes a look at the independent organization that makes recommendations about how CSS, as well as a variety of other web-specific languages, should be used and implemented. -

Acceptable Use of Instant Messaging Issued by the CTO

State of West Virginia Office of Technology Policy: Acceptable Use of Instant Messaging Issued by the CTO Policy No: WVOT-PO1010 Issued: 11/24/2009 Revised: 12/22/2020 Page 1 of 4 1.0 PURPOSE This policy details the use of State-approved instant messaging (IM) systems and is intended to: • Describe the limitations of the use of this technology; • Discuss protection of State information; • Describe privacy considerations when using the IM system; and • Outline the applicable rules applied when using the State-provided system. This document is not all-inclusive and the WVOT has the authority and discretion to appropriately address any unacceptable behavior and/or practice not specifically mentioned herein. 2.0 SCOPE This policy applies to all employees within the Executive Branch using the State-approved IM systems, unless classified as “exempt” in West Virginia Code Section 5A-6-8, “Exemptions.” The State’s users are expected to be familiar with and to comply with this policy, and are also required to use their common sense and exercise their good judgment while using Instant Messaging services. 3.0 POLICY 3.1 State-provided IM is appropriate for informal business use only. Examples of this include, but may not be limited to the following: 3.1.1 When “real time” questions, interactions, and clarification are needed; 3.1.2 For immediate response; 3.1.3 For brainstorming sessions among groups; 3.1.4 To reduce chances of misunderstanding; 3.1.5 To reduce the need for telephone and “email tag.” 3.2 Employees must only use State-approved instant messaging. -

Geotagging Photos to Share Field Trips with the World During the Past Few

Geotagging photos to share field trips with the world During the past few years, numerous new online tools for collaboration and community building have emerged, providing web-users with a tremendous capability to connect with and share a variety of resources. Coupled with this new technology is the ability to ‘geo-tag’ photos, i.e. give a digital photo a unique spatial location anywhere on the surface of the earth. More precisely geo-tagging is the process of adding geo-spatial identification or ‘metadata’ to various media such as websites, RSS feeds, or images. This data usually consists of latitude and longitude coordinates, though it can also include altitude and place names as well. Therefore adding geo-tags to photographs means adding details as to where as well as when they were taken. Geo-tagging didn’t really used to be an easy thing to do, but now even adding GPS data to Google Earth is fairly straightforward. The basics Creating geo-tagged images is quite straightforward and there are various types of software or websites that will help you ‘tag’ the photos (this is discussed later in the article). In essence, all you need to do is select a photo or group of photos, choose the "Place on map" command (or similar). Most programs will then prompt for an address or postcode. Alternatively a GPS device can be used to store ‘way points’ which represent coordinates of where images were taken. Some of the newest phones (Nokia N96 and i- Phone for instance) have automatic geo-tagging capabilities. These devices automatically add latitude and longitude metadata to the existing EXIF file which is already holds information about the picture such as camera, date, aperture settings etc. -

HTML5 for .NET Developers by Jim Jackson II Ian Gilman

S AMPLE CHAPTER Single page web apps, JavaScript, and semantic markup Jim Jackson II Ian Gilman FOREWORD BY Scott Hanselman MANNING HTML5 for .NET Developers by Jim Jackson II Ian Gilman Chapter 1 Copyright 2013 Manning Publications brief contents 1 ■ HTML5 and .NET 1 2 ■ A markup primer: classic HTML, semantic HTML, and CSS 33 3 ■ Audio and video controls 66 4 ■ Canvas 90 5 ■ The History API: Changing the game for MVC sites 118 6 ■ Geolocation and web mapping 147 7 ■ Web workers and drag and drop 185 8 ■ Websockets 214 9 ■ Local storage and state management 248 10 ■ Offline web applications 273 vii HTML5 and .NET This chapter covers ■ Understanding the scope of HTML5 ■ Touring the new features in HTML5 ■ Assessing where HTML5 fits in software projects ■ Learning what an HTML application is ■ Getting started with HTML applications in Visual Studio You’re really going to love HTML5. It’s like having a box of brand new toys in front of you when you have nothing else to do but play. Forget pushing the envelope; using HTML5 on the client and .NET on the server gives you the ability to create entirely new envelopes for executing applications inside browsers that just a few years ago would have been difficult to build even as desktop applications. The abil- ity to use the skills you already have to build robust and fault-tolerant .NET solu- tions for any browser anywhere gives you an advantage in the market that we hope to prove throughout this book. For instance, with HTML5, you can ■ Tap the new Geolocation API to locate your users anywhere -

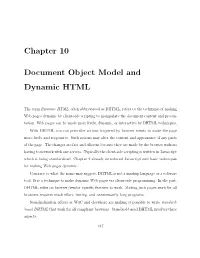

Chapter 10 Document Object Model and Dynamic HTML

Chapter 10 Document Object Model and Dynamic HTML The term Dynamic HTML, often abbreviated as DHTML, refers to the technique of making Web pages dynamic by client-side scripting to manipulate the document content and presen- tation. Web pages can be made more lively, dynamic, or interactive by DHTML techniques. With DHTML you can prescribe actions triggered by browser events to make the page more lively and responsive. Such actions may alter the content and appearance of any parts of the page. The changes are fast and e±cient because they are made by the browser without having to network with any servers. Typically the client-side scripting is written in Javascript which is being standardized. Chapter 9 already introduced Javascript and basic techniques for making Web pages dynamic. Contrary to what the name may suggest, DHTML is not a markup language or a software tool. It is a technique to make dynamic Web pages via client-side programming. In the past, DHTML relies on browser/vendor speci¯c features to work. Making such pages work for all browsers requires much e®ort, testing, and unnecessarily long programs. Standardization e®orts at W3C and elsewhere are making it possible to write standard- based DHTML that work for all compliant browsers. Standard-based DHTML involves three aspects: 447 448 CHAPTER 10. DOCUMENT OBJECT MODEL AND DYNAMIC HTML Figure 10.1: DOM Compliant Browser Browser Javascript DOM API XHTML Document 1. Javascript|for cross-browser scripting (Chapter 9) 2. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)|for style and presentation control (Chapter 6) 3. Document Object Model (DOM)|for a uniform programming interface to access and manipulate the Web page as a document When these three aspects are combined, you get the ability to program changes in Web pages in reaction to user or browser generated events, and therefore to make HTML pages more dynamic. -

How-To Guide: Copy and Adjust Skins (SAP CRM 7.0).Pdf

How-to Guide: Copy and Adjust Skins ® SAP CRM 7.0 Target Audience System administrators Technology consultants Document version: 1.1 – December 2008 SAP AG Dietmar-Hopp-Allee 16 69190 Walldorf Germany T +49/18 05/34 34 24 F +49/18 05/34 34 20 www.sap.com © Copyright 2007 SAP AG. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without the express permission of SAP AG. The information contained herein may be changed without prior notice. SAP, R/3, mySAP, mySAP.com, xApps, xApp, SAP NetWeaver, and other SAP products and services mentioned herein as well as their Some software products marketed by SAP AG and its distributors respective logos are trademarks or registered trademarks of SAP AG contain proprietary software components of other software vendors. in Germany and in several other countries all over the world. All other product and service names mentioned are the trademarks of their Microsoft, Windows, Outlook, and PowerPoint are registered respective companies. Data contained in this document serves trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. informational purposes only. National product specifications may vary. IBM, DB2, DB2 Universal Database, OS/2, Parallel Sysplex, MVS/ESA, AIX, S/390, AS/400, OS/390, OS/400, iSeries, pSeries, These materials are subject to change without notice. These materials xSeries, zSeries, z/OS, AFP, Intelligent Miner, WebSphere, Netfinity, are provided by SAP AG and its affiliated companies ("SAP Group") Tivoli, Informix, i5/OS, POWER, POWER5, OpenPower and for informational purposes only, without representation or warranty of PowerPC are trademarks or registered trademarks of IBM Corporation. -

Head First HTML with CSS & XHTML

Head First HTML with CSS & XHTML Wouldn’t it be dreamy if there was an HTML book that didn’t assume you knew what elements, attributes, validation, selectors, and pseudo-classes were, all by page three? It’s probably just a fantasy... Elisabeth Freeman Eric Freeman Beijing • Cambridge • Köln • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Head First HTML with CSS and XHTML by Elisabeth Freeman and Eric Freeman Copyright © 2006 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly Media books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Associate Publisher: Mike Hendrickson Series Creators: Kathy Sierra, Bert Bates Series Advisors: Elisabeth Freeman, Eric Freeman Editor: Brett McLaughlin Cover Designers: Ellie Volckhausen, Karen Montgomery HTML Wranglers: Elisabeth Freeman, Eric Freeman Structure: Elisabeth Freeman Style: Eric Freeman Page Viewer: Oliver Printing History: December 2005: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The Head First series designations, Head First HTML with CSS and XHTML, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc., was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. -

Tag Recommendations in Social Bookmarking Systems

1 Tag Recommendations in Social Bookmarking Systems Robert Jaschke¨ a,c Leandro Marinho b,d 1. Introduction Andreas Hotho a Lars Schmidt-Thieme b Gerd Stumme a,c Folksonomies are web-based systems that allow users to upload their resources, and to label them with a Knowledge & Data Engineering Group (KDE), arbitrary words, so-called tags. The systems can be dis- University of Kassel, tinguished according to what kind of resources are sup- 1 Wilhelmshoher¨ Allee 73, 34121 Kassel, Germany ported. Flickr , for instance, allows the sharing of pho- tos, del.icio.us2 the sharing of bookmarks, CiteULike3 http://www.kde.cs.uni-kassel.de 4 b and Connotea the sharing of bibliographic references, Information Systems and Machine Learning Lab and last.fm5 the sharing of music listening habits. Bib- (ISMLL), University of Hildesheim, 6 Sonomy allows to share bookmarks and BIBTEX based Samelsonplatz 1, 31141 Hildesheim, Germany publication entries simultaneously. http://www.ismll.uni-hildesheim.de In their core, these systems are all very similar. Once c Research Center L3S, a user is logged in, he can add a resource to the sys- Appelstr. 9a, 30167 Hannover, Germany tem, and assign arbitrary tags to it. The collection of all his assignments is his personomy, the collection of http://www.l3s.de folksonomy d all personomies constitutes the . The user Brazilian National Council Scientific and can explore his personomy, as well as the whole folk- Technological Research (CNPq) scholarship holder. sonomy, in all dimensions: for a given user one can see all resources he has uploaded, together with the tags he Abstract. -

Document Object Model

Document Object Model Copyright © 1999 - 2020 Ellis Horowitz DOM 1 What is DOM • The Document Object Model (DOM) is a programming interface for XML documents. – It defines the way an XML document can be accessed and manipulated – this includes HTML documents • The XML DOM is designed to be used with any programming language and any operating system. • The DOM represents an XML file as a tree – The documentElement is the top-level of the tree. This element has one or many childNodes that represent the branches of the tree. Copyright © 1999 - 2020 Ellis Horowitz DOM 2 Version History • DOM Level 1 concentrates on HTML and XML document models. It contains functionality for document navigation and manipulation. See: – http://www.w3.org/DOM/ • DOM Level 2 adds a stylesheet object model to DOM Level 1, defines functionality for manipulating the style information attached to a document, and defines an event model and provides support for XML namespaces. The DOM Level 2 specification is a set of 6 released W3C Recommendations, see: – https://www.w3.org/DOM/DOMTR#dom2 • DOM Level 3 consists of 3 different specifications (Recommendations) – DOM Level 3 Core, Load and Save, Validation, http://www.w3.org/TR/DOM-Level-3/ • DOM Level 4 (aka DOM4) consists of 1 specification (Recommendation) – W3C DOM4, http://www.w3.org/TR/domcore/ • Consolidates previous specifications, and moves some to HTML5 • See All DOM Technical Reports at: – https://www.w3.org/DOM/DOMTR • Now DOM specification is DOM Living Standard (WHATWG), see: – https://dom.spec.whatwg.org