Economic Scenario in the Koch Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17Th Century,Shayesta Khan Appointed As the Local Governor of Bengal

Class-4 BANGLADESH AND GLOBAL STUDIES ( Chapter 14- Our History ) Topic- 2“ The Middle Age” Lecture - 3 Day-3 Date-27/9/20 *** 1st read the main book properly. Middle Ages:The Middle Age or the Medieval period was a period of European history between the fall of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Renaissance. Discuss about three kings of the Middle age: Shamsuddin Ilias Shah: 1.He came to power in the 14th century. 2.His main achievement was to keep Bengal independent from the sultans of Delhi. 3.Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah opened up Shahi dynasty. Isa Khan: 1.Isa Khan was the leader of the landowners in Bengal, called the Baro Bhuiyan. 2.He was the landlord of Sonargaon. 3.In the 16th century, he fought for independence of Bengal against Mughal emperor Akhbar. Shayesta Khan: 1.In the 17th century,Shayesta Khan appointed as the local governor of Bengal. 2.At his time rice was sold cheap.One could get one mound of rice for eight taka only. 3.He drove away the pirates from his region. The social life in the Middle age: 1.At that time Bengal was known for the harmony between Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims. 2.It was also known for its Bengali language and literature. 3.Clothes and diets of Middle age wren the same as Ancient age. The economic life in the Middle age: 1.Their economy was based on agriculture. 2.Cotton and silk garments were also renowned as well as wood and ivory work. 3.Exports exceeded imports with Bengal trading in garments, spices and precious stones from Chattagram. -

Bir Chilarai

Bir Chilarai March 1, 2021 In news : Recently, the Prime Minister of India paid tribute to Bir Chilarai(Assam ‘Kite Prince’) on his 512th birth anniversary Bir Chilarai(Shukladhwaja) He was Nara Narayan’s commander-in-chief and got his name Chilarai because, as a general, he executed troop movements that were as fast as a chila (kite/Eagle) The great General of Assam, Chilarai contributed a lot in building the Koch Kingdom strong He was also the younger brother of Nara Narayan, the king of the Kamata Kingdom in the 16th century. He along with his elder brother Malla Dev who later known as Naya Narayan attained knowledge about warfare and they were skilled in this art very well during their childhood. With his bravery and heroism, he played a crucial role in expanding the great empire of his elder brother, Maharaja Nara Narayan. He was the third son of Maharaja Biswa Singha (1523–1554 A.D.) The reign of Maharaja Viswa Singha marked a glorious episode in the history of Assam as he was the founder ruler of the Koch royal dynasty, who established his kingdom in 1515 AD. He had many sons but only four of them were remarkable. With his Royal Patronage Sankardeva was able to establish the Ek Saran Naam Dharma in Assam and bring about his cultural renaissance. Chilaray is said to have never committed brutalities on unarmed common people, and even those kings who surrendered were treated with respect. He also adopted guerrilla warfare successfully, even before Shivaji, the Maharaja of Maratha Empire did. -

Expounding Design Act, 2000 in Context of Assam's Textile

EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR Dissertation submitted to National Law University, Assam in partial fulfillment for award of the degree of MASTER OF LAWS Supervised by, Submitted by, Dr. Topi Basar Anee Das Associate Professor of Law UID- SF0217002 National Law university, Assam 2nd semester Academic year- 2017-18 National Law University, Assam June, 2018 SUPERVISOR CERTIFICATE It is to certify that Miss Anee Das is pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam and has completed her dissertation titled “EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR” under my supervision. The research work is found to be original and suitable for submission. Dr. Topi Basar Date: June 30, 2018 Associate Professor of Law National Law University, Assam DECLARATION I, ANEE DAS, pursuing Master of Laws (LL.M.) from National Law University, Assam, do hereby declare that the present Dissertation titled "EXPOUNDING DESIGN ACT, 2000 IN CONTEXT OF ASSAM’S TEXTILE SECTOR" is an original research work and has not been submitted, either in part or full anywhere else for any purpose, academic or otherwise, to the best of my knowledge. Dated: June 30, 2018 ANEE DAS UID- SF0217002 LLM 2017-18 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To succeed in my research endeavor, proper guidance has played a vital role. At the completion of the dissertation at the very onset, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research guide Dr. Topi Basar, Associate professor of Law who strengthen my knowledge in the field of Intellectual Property Rights and guided me throughout the dissertation work. -

Dimasa Kachari of Assam

ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY NO·7II , I \ I , CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I MONOGRAPH SERIES PART V-B DIMASA KACHARI OF ASSAM , I' Investigation and Draft : Dr. p. D. Sharma Guidance : A. M. Kurup Editing : Dr. B. K. Roy Burman Deputy Registrar General, India OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI CONTENTS FOREWORD v PREFACE vii-viii I. Origin and History 1-3 II. Distribution and Population Trend 4 III. Physical Characteristics 5-6 IV. Family, Clan, Kinship and Other Analogous Divisions 7-8 V. Dwelling, Dress, Food, Ornaments and Other Material Objects distinctive qfthe Community 9-II VI. Environmental Sanitation, Hygienic Habits, Disease and Treatment 1~ VII. Language and Literacy 13 VIII. Economic Life 14-16 IX. Life Cycle 17-20 X. Religion . • 21-22 XI. Leisure, Recreation and Child Play 23 XII. Relation among different segments of the community 24 XIII. Inter-Community Relationship . 2S XIV Structure of Soci141 Control. Prestige and Leadership " 26 XV. Social Reform and Welfare 27 Bibliography 28 Appendix 29-30 Annexure 31-34 FOREWORD : fhe Constitution lays down that "the State shall promote with special care the- educational and economic hterest of the weaker sections of the people and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist States in fulfilling their responsibility in this regard, the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the President under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include in or exclude from the lists, any caste or tribe. -

List of Trainees of Egp Training

Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Summary of Participants # Type of Training No. of Participants 1 Procuring Entity (PE) 876 2 Registered Tenderer (RT) 1593 3 Organization Admin (OA) 59 4 Registered Bank User (RB) 29 Total 2557 Consultancy Services for “e-GP Related Training” Digitizing Implementation Monitoring and Public Procurement Project (DIMAPPP) Contract Package # CPTU/S-03 Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU), IMED Ministry of Planning Training Time Duration: 1st July 2020- 30th June 2021 Number of Procuring Entity (PE) Participants: 876 # Name Designation Organization Organization Address 1 Auliullah Sub-Technical Officer National University, Board Board Bazar, Gazipur 2 Md. Mominul Islam Director (ICT) National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 3 Md. Mizanoor Rahman Executive Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 4 Md. Zillur Rahman Assistant Maintenance Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 5 Md Rafiqul Islam Sub Assistant Engineer National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 6 Mohammad Noor Hossain System Analyst National University Board Bazar, Gazipur 7 Md. Anisur Rahman Programmer Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-999 8 Sanjib Kumar Debnath Deputy Director Ministry Of Land Bangladesh Secretariat Dhaka-1000 9 Mohammad Rashedul Alam Joint Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 10 Md. Enamul Haque Assistant Director(Construction) Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 11 Nazneen Khanam Deputy Director Bangladesh Rural Development Board 5,Kawranbazar, Palli Bhaban, Dhaka-1215 12 Md. -

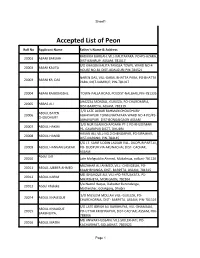

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

Prof. Nataraju Adarasupally

Assam University (Central) +91-9435522165 +91-6001595543 [email protected] PROF. NATARAJU ADARASUPALLY Prof. Adarasupally Nataraju Dean, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan School of Philosophical Studies , A.U- 2014 to 2017, And Second term from February 2020. UGC-SAP DRS-I Coordinator—2014-2018 Visiting Professor: Mahachula Longkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. WORK HISTORY PROFESSOR IN PHILOSOPHY, ASSAM CENTRAL UNIVERSITY— 1. Dean, School of Philosophical Studies, Assam University, Silchar, from February 2014 to Feb, 2017 . second term from Feb.2020 till present. 2. Head, Department of Philosophy, Assam University, From September 2012 to Present. 07 years. 3. Member, Board of Research Studies, Member, Academic Council-- Assam University. 4. Member, Board of Research Studies, NEHU, Shillong. 5. Director, Sports Board-Assam University. From September 2018 till Present RESEARCH 1. A Major Research Project on “The Limits of Thought: Limit Contradictions, PROJECTS Limit Concepts in the (Neo) Vedanta Philosophy” is a completed project with ICPR, New Delhi Financial Assistance. This project was for a period of three years. 2012-2015 (Grant money; 7 Lakhs). Final report submitted. 2. A Minor research Project on ‘Painless Civilization: Ethical Challenges to Human Bio-Technology’. This work was under SAP, UGC-DRS-1. Final report submitted. Books Publication/ Chapters in Books 1. Blooms Bury, London (New Delhi),has published an edited volume on “ The Limits of Thought and Beyond”, July 2013. 2. Munshiram Manoharlal, (In Press)-- “J Krishnamurti”, this book is under the “Builders of Modern Indian Philosophy Series”, General Editor- late Prof R. Balasubramanian. 3. Blooms Bury, New Delhi , Edited volume on “On the Nature of Consciousness’ , released in July, 2018. -

Muga Silk Rearers: a Field Study of Lakhimpur District of Assam

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 04, APRIL 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Muga Silk Rearers: A Field Study Of Lakhimpur District Of Assam Bharat Bonia Abstract: Assam the centre of North- East India is a highly fascinated state with play to with biodiversity and wealth of natural resource. Lakhimpur is an administrative district in the state of Assam, India. Its headquarter is North Lakhimpur. Lakhimpur district is surrounded by North by Siang and Papumpare district of Arunachal Pradesh and on the East by Dhemaji District and Subansiri River. The geographical location of the district is 26.48’ and 27.53’ Northern latitude and 93.42’ and 94.20' East longitude (approx.). Their existence of rare variety of insects and plants, orchids along various wild animals, birds. And the rest of the jungle and sanctuaries of Assam exerts a great contribution to deliberation of human civilization s. Among all these a peculiar kind of silkworm “Mua” sensitive by nature, rare and valuable living species that makes immense impact on the economy of the state of Assam and Lakhimpur district and paving the way for the muga industry. A Muga silkworm plays an important role in Assamsese society and culture. It also has immense impacts on Assams economy and also have an economic impacts on the people of Lakhimpur district which are specially related with muga rearing activities. Decades are passes away; the demand of Muga is increasing day by day not only in Assam but also in other countries. But the ratio of muga silk production and its demand are disproportionate. -

![[ for Wednesday,10Th March 2021]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4210/for-wednesday-10th-march-2021-1424210.webp)

[ for Wednesday,10Th March 2021]

THE GAUHATI HIGH COURT AT GUWAHATI (The High Court of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh) DAILY CAUSELIST [PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE] Web:www.ghconline.gov.in [ For Wednesday,10th March 2021] [ALL MENTION FOR LISTING OF CASES AND FOR ANY URGENT MATTER MUST BE MADE AT 10:30 AM BEFORE RESPECTIVE BENCHES] [HON'BLE COURTS WILL TAKE UP PART - II HEARING LIST ON ALL MOTION DAYS AFTER COMPLETION OF DAILY LIST, IF TIME PERMITS] [AT 10:30 AM ] BEFORE: HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE MANASH RANJAN PATHAK COURT NO: 1 [DIVISION BENCH - I] -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sr.No. Case Number Main Parties Petitioner Advocate Respondent Advocate -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MOTION 1 WP(C)/1032/2020 SONAPUR HERBAL CENTRE PVT. LTD. Mukesh Sharma MR S DUTTA WITH LCR, FIXED Versus MRS. A GAYAN UNION OF INDIA AND 3 ORS. MR K KASHYAB MR A HUSSAIN ASSTT.S.G.I. WITH I.A.(Civil)/1870/2020 SONAPUR HERBAL CENTRE PVT. LTD. Mukesh Sharma ASSTT.S.G.I. in WP(C)/1032/2020 Versus UNION OF INDIA AND 3 ORS. WITH I.A.(Civil)/403/2021 SONAPUR HERBAL CENTRE PVT. LTD. Mukesh Sharma ASSTT.S.G.I. in WP(C)/1032/2020 Versus SC, PNB UNION OF INDIA AND 3 ORS. WITH 2 FAO/33/2017 SONAPUR HERBAL CENTRE PRIVATE MR.S P ROY MR.A GANGULY LIMITED MR. N ALAM MR.S DUTTA Versus MRA K RAI SC, PNB PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK and ANR MR.P N SHARMA WITH I.A.(Civil)/1727/2017 SONAPUR HERBAL CENTRE PRIVATE MR.S P ROY MR.A GANGULY in FAO/33/2017 LIMITED MR. -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

SUFIS and THEIR CONTRIBUTION to the CULTURAL LIFF of MEDIEVAL ASSAM in 16-17"' CENTURY Fttasfter of ^Hilojiopl)?

SUFIS AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO THE CULTURAL LIFF OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM IN 16-17"' CENTURY '•"^•,. DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fttasfter of ^hilojiopl)? ' \ , ^ IN . ,< HISTORY V \ . I V 5: - • BY NAHIDA MUMTAZ ' Under the Supervision of DR. MOHD. PARVEZ CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2010 DS4202 JUL 2015 22 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh-202 002 Dr. Mohd. Parwez Dated: June 9, 2010 Reader To Whom It May Concern This is to certify that the dissertation entitled "Sufis and their Contribution to the Cultural Life of Medieval Assam in 16-17^^ Century" is the original work of Ms. Nahida Muxntaz completed under my supervision. The dissertation is suitable for submission and award of degree of Master of Philosophy in History. (Dr. MoMy Parwez) Supervisor Telephones: (0571) 2703146; Fax No.: (0571) 2703146; Internal: 1480 and 1482 Dedicated To My Parents Acknowledgements I-11 Abbreviations iii Introduction 1-09 CHAPTER-I: Origin and Development of Sufism in India 10 - 31 CHAPTER-II: Sufism in Eastern India 32-45 CHAPTER-in: Assam: Evolution of Polity 46-70 CHAPTER-IV: Sufis in Assam 71-94 CHAPTER-V: Sufis Influence in Assam: 95 -109 Evolution of Composite Culture Conclusion 110-111 Bibliography IV - VlU ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of my teachers and friends from whose help and advice I have benefited. It is a rare obligation to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Mohd. -

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO.