Amsterdam : Water : Brick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson

An Examination of the Potential Influence of Karl Friedrich Schinkel on the Work of Alexander 'Greek' Thomson A Thesis submitted by: Andre Weiss B. A. 1998 Supervisor: Dr. Gavin Stamp Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture Mackintosh School of Architecture, The University of Glasgow September 1999 ProQuest N um ber: 13833922 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13833922 Published by ProQuest LLC(2019). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Contents List of Illustrations ...................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1. The Previous Claims of an InfluentialRelationship ............................................18 2. An Exploration of the Individual Backgrounds of Thomson and Schinkel .............................................................................................................38 -

Class, Nation and the Folk in the Works of Gustav Freytag (1816-1895)

Private Lives and Collective Destinies: Class, Nation and the Folk in the Works of Gustav Freytag (1816-1895) Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benedict Keble Schofield Department of Germanic Studies University of Sheffield June 2009 Contents Abstract v Acknowledgements vi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Literature and Tendenz in the mid-19th Century 1 1.2 Gustav Freytag: a Literary-Political Life 2 1.2.1 Freytag's Life and Works 2 1.2.2 Critical Responses to Freytag 4 1.3 Conceptual Frameworks and Core Terminology 10 1.4 Editions and Sources 1 1 1.4.1 The Gesammelte Werke 1 1 1.4.2 The Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben 12 1.4.3 Letters, Manuscripts and Archival Material 13 1.5 Structure of the Thesis 14 2 Political and Aesthetic Trends in Gustav Freytag's Vormiirz Poetry 17 2.1 Introduction: the Path to Poetry 17 2.2 In Breslau (1845) 18 2.2.1 In Breslau: Context, Composition and Theme 18 2.2.2 Politically Responsive Poetry 24 2.2.3 Domestic and Narrative Poetry 34 2.2.4 Poetic Imagination and Political Engagement 40 2.3 Conclusion: Early Concerns and Future Patterns 44 3 Gustav Freytag's Theatrical Practice in the 1840s: the Vormiirz Dramas 46 3.1 Introduction: from Poetry to Drama 46 3.2 Die Brautfahrt, oder Kunz von der Rosen (1841) 48 3.2.1 Die Brautfahrt: Context, Composition and Theme 48 3.2.2 The Hoftheater Competition of 1841: Die Brautfahrt as Comedy 50 3.2.3 Manipulating the Past: the Historical Background to Die Brautfahrt 53 3.2.4 The Question of Dramatic Hero: the Function ofKunz 57 3.2.5 Sub-Conclusion: Die -

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR: From Rejection to Selective Commemoration Corinna Munn Department of History Columbia University April 9, 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Volker Berghahn, for his support and guidance in this project. I also thank my second reader, Hana Worthen, for her careful reading and constructive advice. This paper has also benefited from the work I did under Wolfgang Neugebauer at the Humboldt University of Berlin in the summer semester of 2013, and from the advice of Bärbel Holtz, also of Humboldt University. Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Chronology and Context………………………………………………………….4 3. The Geschichtsbild in the GDR…………………………………………………..8 3.1 What is a Geschichtsbild?..............................................................................8 3.2 The Function of the Geschichtsbild in the GDR……………………………9 4. Prussia’s Changing Role in the Geschichtsbild of the GDR…………………….11 4.1 1945-1951: The Post-War Period………………………………………….11 4.1.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………11 4.1.2 Public Symbols and Events: The fate of the Berliner Stadtschloss…14 4.1.3 Film: Die blauen Schwerter………………………………………...19 4.2 1951-1973: Building a Socialist Society…………………………………...22 4.2.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………22 4.2.2 Public Symbols and Events: The Neue Wache and the demolition of Potsdam’s Garnisonkirche…………………………………………..30 4.2.3 Film: Die gestohlene Schlacht………………………………………34 4.3 1973-1989: The Rediscovery of Prussia…………………………………...39 4.3.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………39 4.3.2 Public Symbols and Events: The restoration of the Lindenforum and the exhibit at Sans Souci……………………………………………42 4.3.3 Film: Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria………………………..45 5. -

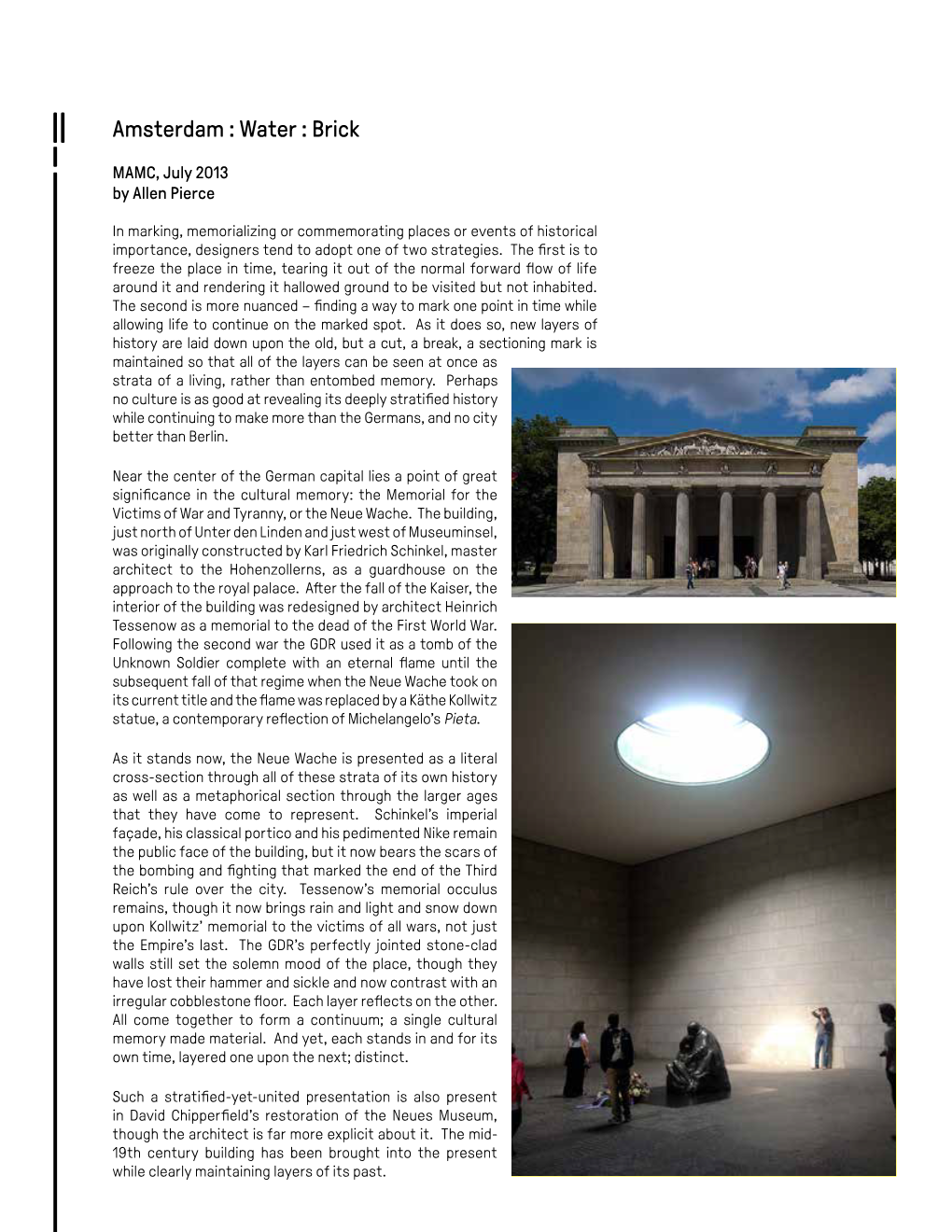

Neue Wache (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the Berlin Neue Wache Has Served As a Central Memorial Comm

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI 2011, No 1 ZbIGNIEw MAZuR Poznań NEUE WACHE (1818-1993) Since 1993 in the Federal Republic of Germany the berlin Neue wache has served as a central memorial commemorating the victims of war and tyranny, that is to say it represents in a synthetic gist the binding German canon of collective memo- ry in the most sensitive area concerning the infamous history of the Third Reich. The interior decor of Neue wache, the sculpture placed inside and the commemorative plaques speak a lot about the official historical policy of the German government. Also the symbolism of the place itself is of significance, and a plaque positioned to the left of the entrance contains information about its history. Indeed, the history of Neue wache was extraordinary, starting as a utility building, though equipped with readable symbolic features, and ending up as a place for a national memorial which has been redesigned three times. Consequently, the process itself created a symbolic palimpsest with some layers completely obliterated and others remaining visible to the eye, and with new layers added which still retain a scent of freshness. The first layer is very strongly connected with the victorious war of “liberation” against Na- poleonic France, which played the role of a myth that laid the foundations for the great power of Prussia and then of the later German Empire. The second layer was a reflection of the glorifying worship of the fallen soldiers which developed after world war I in European countries and also in Germany. The third one was an ex- pression of the historical policy of the communist-run German Democratic Republic which emphasized the victims of class struggle with “militarism” and “fascism”. -

Architecture in Berlin. a Walk Through History Instructor

Course title: Architecture in Berlin. A Walk through History Instructor: Dr. Gernot Weckherlin Email address: [email protected] Track: A-Track Language of instruction: English Contact hours: 48 (6 per day) ECTS-Credits: 5 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2) or higher. Course description This course gives a wide overview of the development of public and private architecture in Berlin during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following an introduction to the urban development and architectural history of the Modern era, the Neo-Classical period will be surveyed with special reference to the works of Schinkel. This will be followed by classes on architecture of the German Reich after 1871, which was characterized by both modern and conservative tendencies and the manifold activities during the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s such as the Housing Revolution. The architecture of the Nazi period will be examined, followed by the developments in East and West Berlin after the Second World War. The course concludes with a detailed review of the city’s more recent and current architectural profiles, including an analysis of the conflicts concerning the re-design of Berlin after the Cold War and the German reunification. Seven walking tours to historically significant buildings and sites are included (Unter den Linden, Gendarmenmarkt, New Housing Estates, Chancellory, Potsdamer Platz, Holocaust Memorial etc.). The course aims to offer a deeper understanding of the interdependence of Berlin’s architecture and the city’s social and political structures. It considers Berlin as a model for the highways and by-ways of a European capital in modern times. -

Altona War Memorials.Pages

ALTONA MEMORIAL DRINKING FOUNTAIN by Ann Cassar GIFT TO ALTONA A memorial commemorating those who lost their lives while serving in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I 1914-1918 (Great War), unveiled in 1928 on the tenth anniversary after the war ended Fig 1 - Image from Altona Laverton Historical Society collection, circa 1929 Located at the northern end of Altona pier on the Esplanade, the memorial was a gift to the community from the recently formed Ex-Service Men and Women’s Club, now better known as the Altona RSL (Returned Services League) and local residents who generously donated to the cause. The memorial was unveiled on Monday, 4 June 1928 on the day when the King’s birthday was celebrated, and 10 years after the end of WWI. Fig 2 - Request for tenders published in The Age, Thursday, 1 Mar 1928 Jack Hopkins, treasurer of the Ex-Service Men and Women’s Club, designed the memorial and carried out much of its construction starting on 1 May 1928, just one month before the unveiling. Constructed of concrete, it had four alcoves, one on each side and when completed there would be a tap in each to supply unlimited quantities the world’s oldest brew, “Adam’s Ale.” It was surmounted by a dome on top and would be further embellished as funds became available. The completed memorial stood eight feet high (2.4mt) with two drinking taps. A plaque had been mounted above the front opening bearing the words Erected by Altona Ex-Service Men & Womens Club 1914-1918 “Lest We Forget.” Opening Ceremony In a ceremony beginning at 3pm on Monday, 4 June 1928, the day when the King’s birthday was celebrated. -

The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 The Cost of Memorializing: Analyzing Armenian Genocide Memorials and Commemorations in the Republic of Armenia and in the Diaspora Sabrina Papazian HCM 7: 55–86 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.534 Abstract In April of 1965 thousands of Armenians gathered in Yerevan and Los Angeles, demanding global recognition of and remembrance for the Armenian Genocide after fifty years of silence. Since then, over 200 memorials have been built around the world commemorating the vic- tims of the Genocide and have been the centre of hundreds of marches, vigils and commemorative events. This article analyzes the visual forms and semiotic natures of three Armenian Genocide memorials in Armenia, France and the United States and the commemoration prac- tices that surround them to compare and contrast how the Genocide is being memorialized in different Armenian communities. In doing so, this article questions the long-term effects commemorations have on an overall transnational Armenian community. Ultimately, it appears that calls for Armenian Genocide recognition unwittingly categorize the global Armenian community as eternal victims, impeding the develop- ment of both the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora. Keywords: Armenian Genocide, commemoration, cultural heritage, diaspora, identity, memorials HCM 2019, VOL. 7 Downloaded from Brill.com10/05/202155 12:33:22PM via free access PAPAZIAN Introduction On 24 April 2015, the hundredth anniversary of the commencement of the Armenian Genocide, Armenians around the world collectively mourned for and remembered their ancestors who had lost their lives in the massacres and deportations of 1915.1 These commemorations took place in many forms, including marches, candlelight vigils, ceremo- nial speeches and cultural performances. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

Cruise Tour MOBY

Helsinki & Saint-Petersburg & Tallinn Itinerary for 6 days/5 nights program with hotel accommodation * 1 day. HELSINKI - ST PETERSBURG NO GUIDE AND NO TRANSPORT Group arriving to port. Onboard cruise to Saint-Petersburg. Dinner onboard. Overnight. 2 day. ST PETERSBURG (Breakfast) Breakfast at the liner -cruise. Arriving at Saint-Petersburg Meeting with the guide and driver. City Tour of St. Petersburg. During the visit, we cross Nevsky prospect- the splendid main avenue with its elegant buildings Gostiniy Dvor (the famous shopping galleries), Zinger House, Stroganov Palace and imposing Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan. Then we cross the island Vasilievskiy- the old port, the university area, we see the golden dome of St. Isaac's Cathedral. Than we turn to the miracle of the Summer Garden, stop at the Champ of Mars at the center of which stands the eternal flame and a breathtaking view of the multicolored domes of the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood opens. Lunch in the restaurant. The Fortress of St. Peter and Paul. It is the historical and architectural center of St. Petersburg. It was the first building of the city founded on May 27, 1703 is considered the date of the founding of St. Petersburg. In the territory of the fortress is the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, which became the Pantheon of the Romanov family, when in 1998 in a side chapel of the Cathedral buried the remains of the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II and his family. Currently the Fortress and the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul is history museum. -

Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin, Vol. 1, Spring 2012 Maria Ebner Fordham University, [email protected]

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Modern Languages and Literatures Student Modern Languages and Literatures Department Publications Spring 2012 Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin, Vol. 1, Spring 2012 Maria Ebner Fordham University, [email protected] Annie Buckel Fordham University James Hollingsworth Fordham University Caroline Inzucchi Fordham University Matthew Kasper Fordham University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/modlang_studentpubs Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, Modern Languages Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ebner, Maria, ed. Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin. Vol. 1, Spring 2012. Bronx, NY: Modern Languages and Literatures Department, Fordham University. Web. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages and Literatures Department at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages and Literatures Student Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Maria Ebner, Annie Buckel, James Hollingsworth, Caroline Inzucchi, Matthew Kasper, Kingsley Lasbrey, Alexander MacLeod, Sean Maguire, Leila Nabizadeh, Kathryn Reddy, Peter Scherer, and Kelsey Taormina This book is available at DigitalResearch@Fordham: https://fordham.bepress.com/modlang_studentpubs/1 ii k i k i zz nn KKK Observations of Berlin k Martyrs & Memories: Seeing Grün: -

Saint-Petersburg – Moscow 8 Days / 7 Nights

GOINGRUSSIA GROUPS 2018 SAINT-PETERSBURG – MOSCOW 8 DAYS / 7 NIGHTS www.goingrussia.com | [email protected] | Tel: +7 812 333 09 54 © 1996-2018 GoingRussia. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced without our prior written permission. ITINERARY SAINT-PETERSBURG – MOSCOW 8D/7N DAY 1 / SAINT-PETERSBURG (ARRIVAL) - Return to Saint-Petersburg - Visit to the Moscow metro - Arrival to Saint-Petersburg - Visit to St. Nicolas Naval Church In option: In option (depending on the arrival time): - Return to the hotel Russian and Cossack folk show Guided walking tour along Nevsky Prospect In option: DAY 6 / MOSCOW Visit of Our Lady of Kazan Cathedral Russian dinner with folk animation at the - Breakfast at the hotel - Transfer to the hotel typical wooden restaurant “Isba Podvorie”, - Visit to the Kremlin and its cathedrals with unlimited vodka and wine DAY 2 / SAINT-PETERSBURG - Free time for lunch - Breakfast at the hotel DAY 4 / SAINT-PETERSBURG - MOSCOW - Visit to the Tretyakov Gallery - Panoramic City Tour - Breakfast at the hotel - Walking tour on Zamoskvorechye area - Visit to the Kuznechny food market - Free morning - Visit to the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour - Exterior visit to the house of Peter the Great In option: In option: - Exterior view of the cruiser Aurora - Excursion to Peterhof and visit of the Grand Performance at the Moscow Circus - Visit to the Peter and Paul Fortress and its Palace, its park, cascades and fountains DAY 7 / MOSCOW - SERGIYEV POSAD - IZMAILOVO cathedral, pantheon of Romanov Tsars - Return to St. Petersburg by hydrofoil - Breakfast at the hotel - Free time for lunch - Transfer to railway station - Excursion to Sergiyev Posad and visit to its - Visit to the Hermitage Museum - Departure to Moscow on high-speed train monastery - Visit of St. -

SHOWCASE Flame Towers - Baku, Azerbaijan

Photography© Florian Licht, Licht und Soehne SHOWCASE Flame Towers - Baku, Azerbaijan Baku Flame Towers is a striking new addition to the skyline of Baku. Located atop a hill on the Caspian Sea overlooking Baku Bay and the old city center, the three towers were inspired by Azerbaijan’s ancient history of fire worshipping, and will illuminate the city and act as an eternal flame for modern Baku. The goal of the project was to create a low-resolution media façade to display video content, while integrating inconspicuous lighting fixtures into existing architecture. To meet the project requirements, Traxon created a special fixture, to be installed behind the buildings’ windows and give the allusion of ribbons of light. The main challenge of this project was the varying window dimensions, and that the maximum gap between fixture and window frame needed to be less than 50mm. With a flexible mounting solution and intelligent calculation, the project team reduced the overall amount of needed fixtures to only 16 different modular lengths. The entire three-tower installation is controlled by an e:cue Lighting Control Engine fx (LCE-fx) running Emotion, and Video Micro Converters (VMCs). Typically displaying burning flames, the intelligent control system allows for simple lighting show changes to reflect additional animations and graphics for special events, such as the recent 2012 Eurovision Song Contest. FEATURED PRODUCTS METHOD OF CONTROL PROJECT DETAILS Category: Architectural Location: Baku, Azerbaijan Client: DIA Holding Lighting Design: Francis