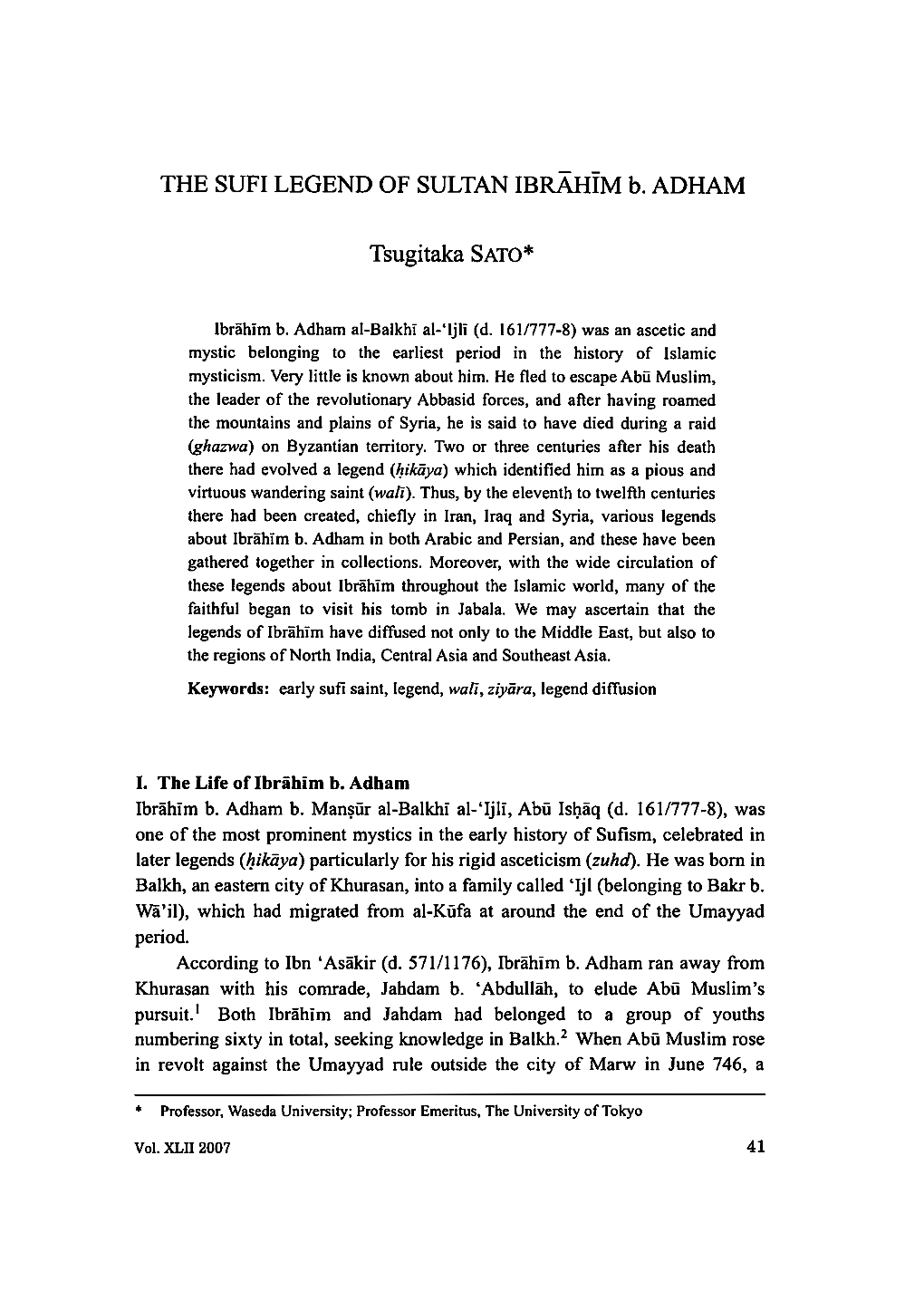

THE SUFI LEGEND of SULTAN IBRAHIM B. ADHAM Tsugitaka SATO*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’S Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests

JUNE 2015 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www.csis.org Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 4501 Forbes Boulevard Lanham, MD 20706 301- 459- 3366 | www.rowman.com Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Russia and Eurasia Program ISBN 978-1-4422-4100-8 Ë|xHSLEOCy241008z v*:+:!:+:! Cover photo: Labusova Olga, Shutterstock.com. Blank Central Asia in a Reconnecting Eurasia Kyrgyzstan’s Evolving Foreign Economic and Security Interests AUTHORS Andrew C. Kuchins Jeffrey Mankoff Oliver Backes A Report of the CSIS Rus sia and Eurasia Program June 2015 Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 594-61689_ch00_3P.indd 1 5/7/15 10:33 AM hn hk io il sy SY eh ek About CSIS hn hk io il sy SY eh ek For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are hn hk io il sy SY eh ek providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart hn hk io il sy SY eh ek a course toward a better world. hn hk io il sy SY eh ek CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analy sis and hn hk io il sy SY eh ek develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Owner\My Documents\Sounds of Silk Booklet.Php

Sounds of Silk an exhibit of Instruments and Textiles from Silk Road Cultures The Silk Road passed through Central Asia, linking China in the east to Iran and the Mediterranean to the west. Connecting pathways went north to Russia and south to India and Afghanistan. Central Asia was inhabited by nomadic and settled peoples whose lives revolved economically around the Silk Road. They also absorbed new ideas and influences through contact with incoming traders, travelers and conquerors. In this exhibition of Central Asian arts, you can see the legacy of the Silk Road in the blending of these foreign ideas with the existing cultural patterns of both nomadic and settled peoples. Funded in part by Utah Humanities Council, Utah Arts Council, and Salt Lake County Zoo Arts and Parks Program. Utah Humanities Council promotes understanding of human traditions, Studies reveal that it was monks who first brought cocoons to Byzantium from China in the year 555 A.D.; the cocoon trade spread from Byzantium to Greece and from there to Italy, Spain and France from the 7th Century onward. The caravans of merchants either followed the road leading to the Caspian Sea by passing through the Afghan valleys, or climbed the Karakorum Mountains and arrived in Anatolia via Iran. From Anatolia, the caravans proceeded to Europe either by sea or by the Silk Road that passed through the Thrace Region. During the time of the Mongols with Ghengiz Khan in the 13th and 14th centuries Marco Polo took the Silk Road to reach China. Even today, the Silk Road offers an extraordinary variety of historic and cultural riches. -

Uzbekistaninitiative

uzbekistaninitiative Uzbekistan Initiative Papers No. 9 February 2014 Seeking Divine Harmony: Uzbek Artisans and their Spaces Gül Berna Özcan Royal Holloway, University of London, UK Key Points - • DespiteCentral Asia.extensive Soviet purges and the state monopoly in manufacturing, Uz bekistan today still remains home to the most fascinating artisanal traditions in • Forinto morepottery. than a millennium, great masters and their disciples have expressed their virtuosity in weaving silk, shaping metals, carving wood, and turning mud - • The most fascinating region, rich with such traditions, is the Fergana Valley where, dotted along a stretch of the ancient Silk Road, numerous small towns are special ized in particular crafts. • Throughlivelihood. tireless repetition of time-honored practices, many artisans and families have managed to maintain their crafts as rituals, as well as a source of identity and- • The social fabric of the community is nested in craft production, cottage indus tries and barter trade. Neighbors and relatives frequently cooperate and perform additional tasks. Extensive networks of relatives and friends help with buying and selling. The opinions expressed here are • Uzbek Government praise artisans as symbols of Uzbek national authenticity, those of the author only and do not represent the Uzbekistan sources of pride and generators of jobs. But, there seems to be no real will and Initiative. structure in place to improve the working conditions of artisans. Moreover, trade restrictions, arbitrary customs rules and corruption suffocate small enterprises. IntroductionUzbekistan Initiative Papers No. 9, February 2014 repeatedly shown vocal opposition to external power domination, as seen during the Basmachi The Fergana Valley is the cultural and spiritual- revolts in the 1920s against Soviet expansion and heart of Central Asia. -

RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: Sciences & Economics Review ______

Research Journal of Social Sciences & Economics Review Vol. 2, Issue 1, 2021 (January – March) ISSN 2707-9023 (online), ISSN 2707-9015 (Print) RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: https://doi.org/10.36902/rjsser-vol2-iss1-2021(79-82) Sciences & Economics Review ____________________________________________________________________________________ Analytical Study of Pedagogical Practices of Abul Hasan Ashari (270 AH ...330 AH) * Dr. Hashmat Begum, Assistant Professor ** Dr. Hafiz Muhammad Ibrar Ullah, Assistant Professor (Corresponding Author) *** Dr. Samina Begum, Assistant Professor __________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Abu al Hasan al-Ashari is measured to be a great as well as famous scholar of theology. He competed with philosophers with the power of his knowledge. He was a famous religious scholar of the Abbasi period. During the heyday of Islam, two schools of thought became famous. One school of thought became famous as the Motazilies and the other discipline of thought became known as the Ash'arites. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari remained a supporter of the Mu'tazilites for forty years. Then there was a disagreement with Mu'tazilah about the issue of value. Imam al-Ghazali is one of the leading preachers of his Ash'arite school of thought. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari inherited a passion for collecting books. As a child, he used to collect books from his hobby. Sometimes there are very difficult places in the path of knowledge, only a real student can pass through these places safely. He has been remembered by the Islamic world in very high words. There was a student who drank the ocean of knowledge but his thirst was not quenched. -

The-Darqawi-Way.Pdf

The Darqawi Way Moulay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi Letters from the Shaykh to the Fuqara' 1 First edition copyright Diwan Press 1979 Reprinted 1981 2 The Darqawi Way Letters from the Shaykh to the Fuqara' Moulay al-‘Arabi ad-Darqawi translated by Aisha Bewley 3 Contents Song of Welcome Introduction Foreword The Darqawi Way Isnad of the Tariq Glossary 4 A Song of Welcome Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, I greet you! The West greets the West — Although the four corners are gone And the seasons are joined. In the tongue of the People I welcome you — the man of the time. Wild, in rags, with three hats And wisdom underneath them. You flung dust in the enemy’s face Scattering them by the secret Of a rare sunna the ‘ulama forgot. Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, I love you! The Pole greets the Pole — The centre is everywhere And the circle is complete. We have danced with Darqawa, Supped at their table, yes, And much, much more, I And you have sung the same song, The song of the sultan of love. Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, you said it! Out in the open you gave the gift. Men drank freely from your jug. The cup passed swiftly, dizzily — Until it came into my hand. I have drunk, I have drunk, I am drinking still, the game Is over and the work is done. What is left if it is not this? 5 This wine that is not air, Nor fire, nor earth, nor water. This diamond — I drink it! Oh! Mawlay al-‘Arabi, you greet me! There is no house in which I sit That you do not sit beside me. -

Ibn Ata Allah Al-Iskandari and Al-Hikam Al-‘Ata’Iyya in the Context of Spiritually-Oriented Psychology and Counseling

SPIRITUAL PSYCHOLOGY AND COUNSELING Received: November 13, 2017 Copyright © 2018 s EDAM Revision Received: May 2, 2018 eISSN: 2458-9675 Accepted: June 26, 2018 spiritualpc.net OnlineFirst: August 7, 2018 DOI 10.37898/spc.2018.3.2.0011 Original Article Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari and al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya in the Context of Spiritually-Oriented Psychology and Counseling Selami Kardaş1 Muş Alparslan University Abstract Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari was a Shadhili Sufi known for his work, al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya. Ibn Ata Allah, known for his influential oratorical style, sermons, and conversations, which deeply impacted the masses during his time, reflected these qualities in all his works, especially al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya. Along with this, finding information on the deepest topics of mysticism is possible in his works. His works address the basic concepts of mystical thinking, such as worship and obedience removed from hypocrisy and fame, resignation, surrender, limits, and hope. This study attempts to explain al-Iskandari’s life, works, mystical understanding, contribution to the world of thought, and concepts specifically addressed in his works, like worship and obedience apart from fame and hypocrisy, trust in God, surrender, limits, and hope. Together with this, the study focuses on the prospect of being able to address al-Iskandari and his work, al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya, in particular as a resource particular to spiritually-oriented psychology and psychological counseling through the context of psychology and psychological counseling. Keywords: Ibn Ata Allah al-Iskandari • Al-Hikam al-‘Ata’iyya • Spirituality • Psychology •Psychological counseling Manevi Yönelimli Psikoloji ve Danışma Bağlamında İbn Atâullah el-İskenderî ve el-Hikemü’l-Atâiyye Öz İbn Ataullah el-İskenderi, el-Hikemü’l-Atâiyye adlı eseriyle tanınan Şazelî sûfîdir. -

Urbanization in Central Asia: Challenges, Issues and Prospects

Analytical Report 2013/03 Urbanization in Central Asia: Challenges, Issues and Prospects Tashkent 2013 This report reflects opinions and views of the working group, which may not coincide with the official point of Center for Economic Research, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific and United Nations Development Programme. © Center for Economic Research, 2013 Any presentation of this report or use of its parts can only be done with the written permission; reference to the source is a must. With regard to the questions about copying, translation or acquisition of the printed versions, please refer to the following address: Center for Economic Research, Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 100070, Shota Rustaveli Str., alley 1, building 5. Urbanization in Central Asia: challenges, issues, and prospects Authors and Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Center for Economic Research under the direction of Bakhodur Eshonov (Director) and Ildus Kamilov (Deputy Direc- tor). The project leaders and main authors were Bakhtiyor Ergashev (Research Coordinator) and Bunyod Avliyokulov (Team Leader). The authors include an international consultant, Ivan Safranchuk (Russia), and 14 national consultants in four Central Asian countries: Uzbekistan team: Abdulla Hashimov, Izzatilla Pathiddinov. Kazakhstan team: Meruert Makhmutova, Aytjan Akhmetova, Botagoz Raki- sheva, Kanat Berentaev. Kyrgyzstan team: Liudmila Torgasheva, Murat Suyunbaev, Aina Mamytova, Temir Burzhubaev. Tajikistan team: Mavzuna Karimova, Bakhodir Khabibov, Rakhmatillo Zoyirov, Masudjon Sobirov. Their statistical, reference and analytical materials have formed an important basis on which the regional report has been built. Many colleagues at the CER provided input for the research concept and its drafts during peer-review sessions, including Nishanbay Sirajiddinov (Deputy Director), senior coordinators Talat Shadybaev, Janna Fattakhova, coordina- tors Khusnia Muradova, Orzimurad Gaybullaev, Kamila Muhamedhanova, and others. -

Curriculum & Syllabi

School of Islamic Studies B.A. ISLAMIC STUDIES ENGLISH MEDIUM – EVENING PROGRAMME Duration: Seven Semesters CURRICULUM & SYLLABI 1 SEMESTER I Course S.No. Name of the Course L T P C Code Foundation Courses: 1 ISB1121 Arabic Language & Tajweed 4 0 0 4 2 ISB1122 Communicative English 3 0 0 3 Core Courses: 3 ISB1123 Quran Meaning Word by word: Al Baqara 3 0 0 3 4 ISB1124 Moral & Ethics - Guidance of Prophet (PBUH) 3 0 0 3 Allied Courses: 5 ISB1125 Biography of Prophet (PBUH) & Caliphate 3 0 0 3 Total: 16 SEMESTER II Course S.No. Name of the Course L T P C Code Foundation Courses: 1 ISB1231 Arabic Language & Grammar 4 0 0 4 2 ISB1232 English Language 3 0 0 3 Core Courses: Quran Meaning Word by word: Ala Imran – An 3 ISB1233 3 0 0 3 Nisa 4 ISB1234 Hadeeth - Teachings of Prophet 3 0 0 3 5 ISB1235 Islamic Fiqh - Ibaadath 3 0 0 3 Total: 16 2 SEMESTER III Course S.No. Name of the Course L T P C Code Foundation Courses: 1 ISB2121 Functional Arabic & Grammar 4 0 0 4 Core Courses: Quran Meaning Word by word: Al Maidah – Al 2 ISB2122 3 0 0 3 A’raf 3 ISB2123 Tafseer: At Tawbah & Yousuf 3 0 0 3 4 ISB2124 Islamic Doctrine - Aqeedah 3 0 0 3 5 ISB2125 Islamic Fiqh – Zakath & Hajj 3 0 0 3 Total: 16 SEMESTER IV Course S.No. Name of the Course L T P C Code Foundation Courses: 1 ISB2231 Advanced Arabic 4 0 0 4 Core Courses: 2 ISB2232 Tafseer: Selected Chapters 3 0 0 3 3 ISB2233 Hadith: Abu Dawood 3 0 0 3 4 ISB2234 Principles of Jurisprudence - Adillah 3 0 0 3 Allied Courses: 5 ISB2235 Islamic History - Umayyad Period 3 0 0 3 3 Total: 16 SEMESTER V Course S.No. -

Unit 14 the Caliphate: Ummayads and Abbasids

Roman Empire: UNIT 14 THE CALIPHATE: UMMAYADS AND Political System ABBASIDS* Structure 14.0 Objectives 14.1 Introduction 14.2 The Ummayad Caliphate: Sufyanid Period 14.3 The Ummayad Caliphate: Marwanid Period 14.4 Later Ummayads 14.5 Ummayad Aesthetics and Material Culture 14.5.1 Court Culture 14.5.2 Palaces and Mosques 14.6 Ummayad Economy: Estates, Trade and Irrigation 14.6.1 Settled Agriculture 14.6.2 Ummayad Trade, Urbanism and Suqs 14.7 Ummayad Monarchs and Provinces (Wilayats) 14.8 Fall of the Ummayad Dynasty 14.9 The Abbasid Caliphate: Abbas and Mansur 14.10 The Abbasid Caliphate: Harun and Al-Mamun 14.11 Later Abbasid Caliphs 14.12 The Abbasid Caliphate: Irrigation, Peasants and Estates 14.12.1 Irrigation 14.12.2 Popular Revolts in the Abbasid Caliphate 14.12.3 Forms of Estates under the Abbasids 14.12.4 Tax Farming in the Abbasid Egypt 14.13 Taxes and Diwans under the Abbasids 14.14 Summary 14.15 Keywords 14.16 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 14.17 Suggested Readings 14.18 Instructional Video Recommendations 14.0 OBJECTIVES In this Unit, we will study about the Ummayad and Abbasid Caliphate which were established by Muawiyah I and Abbas As-Saffah respectively. In the same vein the Ummayads continued campaigns and conquests started by the Caliphs — Abu Bakr and Umar. It was the largest empire in terms of geographical extent. But the Caliphate * Dr. Shakir-ul Hassan, Department of History and Culture, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi 267 RomanSocieties Republic in Central developed hereditary tendencies under the Ummayads. -

Isra'iliyat As an Intercultural Knowledge Bridge And

The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies International Journal of Social Science Doi number:http://dx.doi.org/10.9761/JASSS1954 Volume 6 Issue 8 , p. 93-109, October 2013 ISRA’ILIYAT AS AN INTERCULTURAL KNOWLEDGE BRİDGE AND REFLECTIONS ON THE OTTOMAN FOLK CULTURE* KÜLTÜRLERARASI BİR BİLGİ KÖPRÜSÜ OLARAK İSRAİLİYAT VE OSMANLI HALK KÜLTÜRÜNDEKİ YANSIMALARI Prof. Dr. Hidayet AYDAR Istanbul University, Faculty of Divinity, Basic Islamic Studies, Department of Qur’anic Exegesis İstanbul Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Temel İslam Bilimleri Bölümü Tefsir Anabilim Dalı Abstract Isra’iliyat is the general term used to specify knowledge transferred to Islamic culture from some other cultures including Jewish being primary, Christian, Persian, Indian, central Asian, and even Chinese cultures. Since most of this knowledge is transferred from Jews, known as The Israelites, it is called as isra’iliyat. Nevertheless, there was also a considerable amount of knowledge flux from surrounding cultures of the Middle East, where Islam originates. There was a significant knowledge and information flow especially from Christianity, which is a major religion in the region and Byzantine/Greek culture which was a Christian society then. In addition, Persian culture, a significant cradle of culture and civilization in the region, Indian and Chinese cultures, two of the oldest in the world, and fragments of Central-Asian Turkish/Shaman culture constituted the rich repertory of the Islamic culture. Israeli news and information had started transferring to Islamic culture as early as the Prophet Mohammed era. During this era, especially Jewish religious culture had attracted Muslims. Yet the Koran was frequently mentioning the past of the Jewish people, Israeli history, scriptures, prophets, and other major personalities. -

The Central Islamic Lands

77 THEME The Central Islamic 4 Lands AS we enter the twenty-first century, there are over 1 billion Muslims living in all parts of the world. They are citizens of different nations, speak different languages, and dress differently. The processes by which they became Muslims were varied, and so were the circumstances in which they went their separate ways. Yet, the Islamic community has its roots in a more unified past which unfolded roughly 1,400 years ago in the Arabian peninsula. In this chapter we are going to read about the rise of Islam and its expansion over a vast territory extending from Egypt to Afghanistan, the core area of Islamic civilisation from 600 to 1200. In these centuries, Islamic society exhibited multiple political and cultural patterns. The term Islamic is used here not only in its purely religious sense but also for the overall society and culture historically associated with Islam. In this society not everything that was happening originated directly from religion, but it took place in a society where Muslims and their faith were recognised as socially dominant. Non-Muslims always formed an integral, if subordinate, part of this society as did Jews in Christendom. Our understanding of the history of the central Islamic lands between 600 and 1200 is based on chronicles or tawarikh (which narrate events in order of time) and semi-historical works, such as biographies (sira), records of the sayings and doings of the Prophet (hadith) and commentaries on the Quran (tafsir). The material from which these works were produced was a large collection of eyewitness reports (akhbar) transmitted over a period of time either orally or on paper.