Property, People, Or Something in Between?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tissue and Cell

TISSUE AND CELL AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.3 ISSN: 0040-8166 DESCRIPTION . Tissue and Cell is devoted to original research on the organization of cells, subcellular and extracellular components at all levels, including the grouping and interrelations of cells in tissues and organs. The journal encourages submission of ultrastructural studies that provide novel insights into structure, function and physiology of cells and tissues, in health and disease. Bioengineering and stem cells studies focused on the description of morphological and/or histological data are also welcomed. Studies investigating the effect of compounds and/or substances on structure of cells and tissues are generally outside the scope of this journal. For consideration, studies should contain a clear rationale on the use of (a) given substance(s), have a compelling morphological and structural focus and present novel incremental findings from previous literature. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 2.466 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Scopus PubMed/Medline Cambridge Scientific Abstracts Current Awareness in Biological Sciences Current Contents - Life Sciences Embase Embase Science Citation Index Web of Science EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor Pietro Lupetti, University of Siena, Siena, Italy AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK 1 Oct 2021 www.elsevier.com/locate/tice 1 Managing Editor Giacomo Spinsanti, University of Siena, -

Using Open Access Literature to Guide Full-Text Query Formulation Heather A

Using open access literature to guide full-text query formulation Heather A. Piwowar and Wendy W. Chapman Background Much scientific knowledge is contained in the details of the full-text biomedical literature. Most research in automated retrieval presupposes that the target literature can be downloaded and preprocessed prior to query. Unfortunately, this is not a practical or maintainable option for most users due to licensing restrictions, website terms of use, and sheer volume. Scientific article full-text is increasingly queriable through portals such as PubMed Central, Highwire Press, Scirus, and Google Scholar. However, because these portals only support very basic Boolean queries and full text is so expressive, formulating an effective query is a difficult task for users. We propose improving the formulation of full-text queries by using the open access literature as a proxy for the literature to be searched. We evaluated the feasibility of this approach by building a high-precision query for identifying studies that perform gene expression microarray experiments. Methodology and Results We built decision rules from unigram and bigram features of the open access literature. Minor syntax modifications were needed to translate the decision rules into the query languages of PubMed Central, Highwire Press, and Google Scholar. We mapped all retrieval results to PubMed identifiers and considered our query results as the union of retrieved articles across all portals. Compared to our reference standard, the derived full- text query found 56% (95% confidence interval, 52% to 61%) of intended studies, and 90% (86% to 93%) of studies identified by the full-text search met the reference standard criteria. -

Since January 2020 Elsevier Has Created a COVID-19 Resource Centre with Free Information in English and Mandarin on the Novel Coronavirus COVID- 19

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active. Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Editorial overview: Membrane traffic in the time of COVID-19 Frances M. Brodsky and Jennifer L. Stow Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2020, 65:iii–v This overview comes from a themed issue on Membrane Trafficking Edited by Frances M. Brodsky and Jennifer L. Stow https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2020.09.003 0955-0674/© 2020 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Frances M. Brodsky We write this editorial emerging from lockdown in countries across the Division of Biosciences, University College world in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. These have been chal- London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, lenging, frightening, and too often catastrophic times for many. Such times UK lead to evaluation of one’s own enterprise in the context of a global *Corresponding author: Brodsky, Frances M. -

Inhibitors of Target Workflow

Inhibitors of Target Which Substances are Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Target? Potent and Selective COX-2 It is clear that COX-2 plays an important role in tumor and endothelial cell biology. Increased expression of COX-2 occurs in multiple cells within the tumor microenvironment that can impact on angiogenesis. COX-2 appears to: Play a key role in the release and activity of proangiogenic proteins; Result in the production of eicosanoid products TXA2, PGI2, PGE2 that directly stimulate endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in vivo, and Result in enhanced tumor cell, and possibly, vascular endothelial cell survival by upregulation of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and/or activation of PI3K-Akt. Selective pharmacologic inhibition of COX-2 represents a viable therapeutic option for the treatment of malignancies. Agents that selectively inhibit COX-2 demonstrate that chronic treatment for angiogenesis inhibition is feasible. As a continuous research for discovery of new COX-2 inhibitors, new synthetic potent and selective inhibitors of COX-2 are of great interest as antiangiogenic agent. Let’s search for potent and selective inhibitors of Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) versus Cyclooxygenase COX-1. Define the Search Query using the Query builder 1. On the Reaxys home page, click Query builder Copyright 2017 Elsevier B.V. Reaxys, RELX Group and the RE symbol are trade marks of RELX Intellectual Properties SA, used under license. 1 Inhibitors of Target 2. In the Find search fields and forms box, type selectivity The list if filtered to include fields and forms that include the word selectivity. In this case the Selectivity Profile form is displayed. -

Risk & Business Analytics Teach-In

Risk & Business Analytics teach-in November 8, 2018 London 1 | 2 Disclaimer regarding forward-looking statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of Section 27A of the US Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the US Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. These statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or outcomes to differ materially from those currently being anticipated. The terms “outlook”, “estimate”, “project”, “plan”, “intend”, “expect”, “should be”, “will be”, “believe”, “trends” and similar expressions identify forward-looking statements. Factors which may cause future outcomes to differ from those foreseen in forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to: current and future economic, political and market forces; changes in law and legal interpretations affecting the RELX Group intellectual property rights; regulatory and other changes regarding the collection, transfer or use of third party content and data; demand for the RELX Group products and services; competitive factors in the industries in which the RELX Group operates; compromises of our data security systems and interruptions in our information technology systems; legislative, fiscal, tax and regulatory developments and political risks; exchange rate fluctuations; and other risks referenced from time to time in the filings of RELX PLC and, historically, RELX N.V. with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Definitions Underlying figures are additional performance measures used by management, and are calculated at constant currencies, excluding the results of all acquisitions and disposals made in both the year and prior year, assets held for sale, exhibition cycling, and timing effects. -

Current Opinion in Plant Biology

CURRENT OPINION IN PLANT BIOLOGY AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 1369-5266 DESCRIPTION . Excellence paves the way With Current Opinion in Plant Biology Current Opinion in Plant Biology builds on Elsevier's reputation for excellence in scientific publishing and long-standing commitment to communicating high quality reproducible research. It is part of the Current Opinion and Research (CO+RE) suite of journals. All CO+RE journals leverage the Current Opinion legacy - of editorial excellence, high-impact, and global reach - to ensure they are a widely read resource that is integral to scientists' workflow. Expertise: Editors and Editorial Board bring depth and breadth of expertise and experience to the journal. Discoverability: Articles get high visibility and maximum exposure on an industry-leading platform that reaches a vast global audience. The Current Opinion journals were developed out of the recognition that it is increasingly difficult for specialists to keep up to date with the expanding volume of information published in their subject. In Current Opinion in Plant Biology, we help the reader by providing in a systematic manner: 1. The views of experts on current advances in plant biology in a clear and readable form. 2. Evaluations of the most interesting papers, annotated by experts, from the great wealth of original publications. Division of the subject into sections: The subject of plant biology is divided into themed sections which are reviewed regularly to keep them relevant. -

Game Culture: Theory and Practice Instructor: Mr. Chris Vicari Fall 2018

Game Culture: Theory and Practice Instructor: Mr. Chris Vicari Fall 2018 // Lowenstein 304 Email: [email protected] Office Location: Martino 709 Office Hours: By appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION Games are everywhere and over 155 million Americans play them regularly on tabletops and electronic devices across the county. Their prevalence has promoted the medium as a space for expression, art, and meaning-making. Moving beyond the notion of simple entertainment, games are creating provocative experiences to promote change or understanding. This course emphasizes exploration and critical thinking as we discover how games are designed to address issues such as social justice, gender representation, behavioral change, and education. Through analyzing game artifacts and engaging in creative exercises, students will be able to think critically about games and how they are designed. Students will then apply this literacy into their own game projects. This course is open to anyone who is interested in games and their possibilities. LEARNING OBJECTIVES. By participating and completing in this course, students will: 1. Gain familiarity of games and their potential beyond entertainment 2. Know and employ the terminology of games and design 3. Recognize the approaches, strategies, and tools needed to produce interactive experiences. 4. Be able to work as part of a design team. 5. Be more creative, expressive, and analytical about all aspects of game culture. 6. Create game projects via hands-on methods and digital creation tools. COURSE OBJECTIVES 1. Explain and understand the basic concepts and theory in digital media. 2. Explain how media technologies impact today’s digital culture 3. Identify innovations that continue to change how games address complex issues. -

The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology

The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 42 (2010) 337–345 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocel Chemico-genetic identification of drebrin as a regulator of calcium responses Jason C. Mercer a,b,1, Qian Qi a,d,1, Laurie F. Mottram c,1, Mankit Law a,d, Danny Bruce a, Archana Iyer a,d, a e e c a,d, J. Luis Morales , Hiroyuki Yamazaki , Tomoaki Shirao , Blake R. Peterson , Avery August ∗ a Center for Molecular Immunology & Infectious Disease, Department of Veterinary & Biomedical Science, 115 Henning Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, United States b Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 115 Henning Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, United States c Department of Chemistry, 104 Chemistry Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, United States d Immunology & Infectious Disease Graduate Program, 115 Henning Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, United States e Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine, 3-39-22 Showamachi, Maebashi 371, Japan article info abstract Article history: Store-operated calcium channels are plasma membrane Ca2+ channels that are activated by depletion of Received 14 July 2009 intracellular Ca2+ stores, resulting in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which is maintained Received in revised form 9 November 2009 for prolonged periods in some cell types. Increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration serve as signals that Accepted 23 November 2009 activate a number of cellular processes, however, little is known about the regulation of these channels. -

Digital Commons Voluntary Product Accessibility Template (VPAT) / Accessibility Conformance Report Product Information and Scope

Digital Commons Voluntary Product Accessibility Template (VPAT) / Accessibility Conformance Report Product Information and Scope Name of Product Digital Commons Date Last Updated June 30, 2021 Completed by Jay Nemchik (Digital Accessibility Team, Dayton, OH) Nicholas Seow (Digital Commons Consulting Services, Berkeley, CA) Benedek Nyikos (Digital Commons Consulting Services, Berkeley, CA) Document Description This document rates Digital Commons according to the W3C WCAG 2.1 A and AA requirements. Contact for More Information Ted Gies Principal User Experience Specialist [email protected] [email protected] Digital Commons Consulting Services [email protected] Testing Tools and Methods Hands-on keyboard operation Code inspection Firefox Web Developer Toolbar (removing style sheets) Mozilla Firefox 78 and Google Chrome 91 on Windows 10 20H2 JAWS screen reader 18 NVDA screen reader 2020.4 WAVE Extension Color Contrast Analyzer W3C WAI Pages Elsevier Accessibility Checklist: http://romeo.elsevier.com/accessibility_checklist/ Document Sections The review document below includes all WCAG 2.1 A and AA checkpoints and is organized into 7 logical sections: • Visuals • Keyboard • Headings and Structure • Labeling • Multimedia • Usability • Mobile User Experience Pages Covered This VPAT outlines the compliance of the general, public-facing pages of the Digital Commons (DC) platform: All static pages that comprise the default DC implementation, including: • Institutional Repository (IR) Homepage • Browse Collections • Submit Research -

LN-Derived Fibroblastic Reticular Cells and Their Impact on T Cell Response—A Systematic Review

cells Review LN-Derived Fibroblastic Reticular Cells and Their Impact on T Cell Response—A Systematic Review Bianca O. Ferreira 1,† , Lionel F. Gamarra 1,†, Mariana P. Nucci 1,2 , Fernando A. Oliveira 1 , Gabriel N. A. Rego 1 and Luciana Marti 1,* 1 Department of Experimental Research, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo 05652-000, Brazil; [email protected] (B.O.F.); [email protected] (L.F.G.); [email protected] (M.P.N.); [email protected] (F.A.O.); [email protected] (G.N.A.R.) 2 LIM44—Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo 05403-000, Brazil * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-11-2151-1353 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs), usually found and isolated from the T cell zone of lymph nodes, have recently been described as much more than simple structural cells. Originally, these cells were described to form a conduit system called the “reticular fiber network” and for being responsible for transferring the lymph fluid drained from tissues through afferent lymphatic vessels to the T cell zone. However, nowadays, these cells are described as being capable of secreting several cytokines and chemokines and possessing the ability to interfere with the immune response, improving it, and also controlling lymphocyte proliferation. Here, we performed a systematic review of the several methods employed to investigate the mechanisms used by fibroblastic reticular cells to Citation: Ferreira, B.O.; Gamarra, control the immune response, as well as their ability in determining the fate of T cells. -

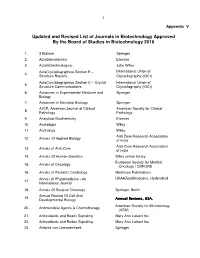

Updated and Revised List of Journals in Biotechnology Approved by the Board of Studies in Biotechnology 2016

1 Appendix V Updated and Revised List of Journals in Biotechnology Approved By the Board of Studies in Biotechnology 2016 1. 3 Biotech Springer 2. ActaBiomaterialia Elsevier 3. ActaBiotechnologica, John Wiley ActaCrystallographica Section E – International Union of 4. Structure Reports Crystallography (IUCr) ActaCrystallographica Section C – Crystal International Union of 5. Structure Communications Crystallography (IUCr) 6. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Springer Biology 7. Advances in Microbial Ecology Springer AJCP, American Journal of Clinical American Society for Clinical 8. Pathology Pathology 9. Analytical Biochemistry Elsevier 10. Andrologia Wiley 11. Andrology Wiley Arid Zone Research Association 12. Annals Of Applied Biology of India Arid Zone Research Association 13. Annals of Arid Zone of India 14. Annals Of Human Genetics Wiley online library European Society for Medical 15. Annals of Oncology Oncology / OXFORD 16. Annals of Pediatric Cardiology Medknow Publications Annals of Phytomedicine - An UKAAZpublicatiuons, Hyderabad 17. International Journal 18. Annals Of Surgical Oncology Springer, Berlin Annual Review Of Cell And 19. Developmental Biology Annual ReviewsReviews,, USAUSA.... American Society for Microbiology 20. Antimicrobial Agents & Chemotherapy (ASM) 21. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling Mary Ann Liebert Inc. 22. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling Mary Ann Liebert Inc. 23. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Springer 2 24. Apoptosis Springer 25. Applied and Environmental Microbiology American Society for Microbiology 26. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology Springer 27. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology Springer, Netherlands 28. Applied Microbiology And Biotechnology Springer & Kluwer 29. Aquaculture Elsevier 30. Aquaculture Nutrition Wiley-Blackwell, Uk 31. Aquaculture Research Wiley-Blackwell, Uk 32. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics Elsevier 33. Archives Of Microbiology Springer 34. Archives Of Toxicology Springer, Berlin Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer 35. -

Q: What Does the Transparent Peer Review Record Include? A: It

Q: What does the Transparent Peer Review Record include? A: It includes: • A basic timeline of the peer review process • A link to the preprint, if it’s available • All versions of the manuscript sent out for peer review (including revisions) • All peer reviews, which are anonymous, unless reviewers choose to sign their reviews • All substantive editorial decision letters (correspondence regarding formatting and similar technical details will be omitted) • The author’s point-by-point responses to reviewers • A section called “Editor’s View” which provides an overview of the editors’ thinking about the manuscript and high-level context about the peer review process Q: Are Transparent papers marked? A: Yes. If the authors of a paper have chosen to make the Transparent Peer Review Record available, this will be stated clearly in the last sentence of the published paper’s abstract. Q: How can I access the Transparent Peer Review Record? A: The Transparent Peer Review Record is part of the published paper’s Supplemental Information. It can be downloaded just like any other part of the Supplement. Q: Are Transparent Peer Review Records Open Access (OA)? A: Yes. All Cell Genomics papers are published OA with a CC-BY license. The Transparent Peer Review Record is part of the published paper and will have the same OA license. Q: Why are you collecting demographic information about the authors of manuscripts submitted to Cell Genomics? What information to I have to disclose about myself? A: We’re asking whether the choice to be transparent impacts all genders, career stages, and geographies equally.