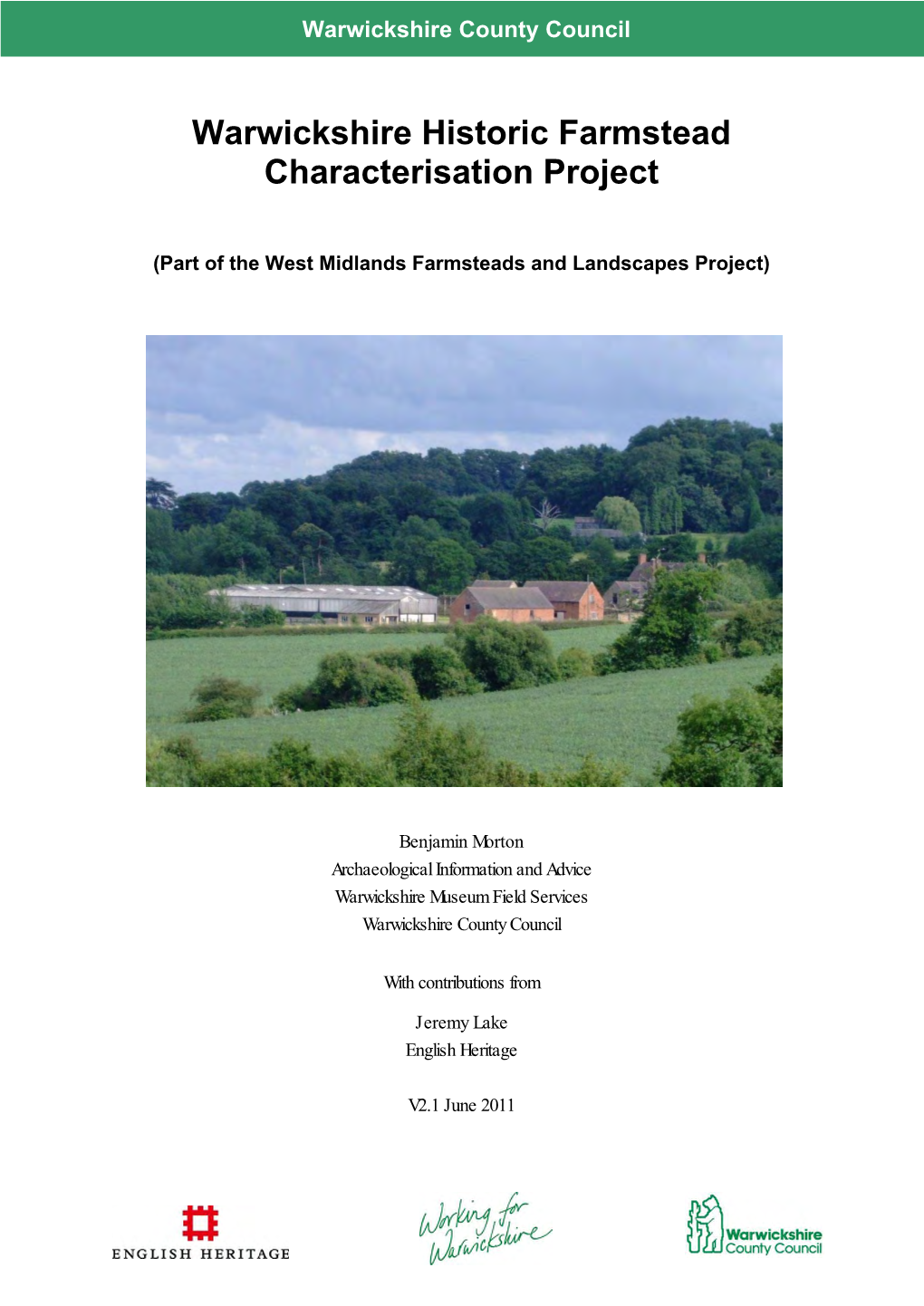

Project Aims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

Warwickshire Museum Collections Development Policy 2020 - 2025

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom Warwickshire Museum Collections Development Policy 2020 - 2025 1 Name of Museum: Warwickshire Museum Name of Governing Body: Warwickshire County Council Date on which this Policy was approved by Warwickshire County Council Cabinet: Day/month/2020 Policy review procedure: The Museum Collections Development Policy will be published and reviewed from time to time and at least once every five years Date at which this policy is due for review: Day/month/2025 Arts Council England will be notified of any changes to the Collections Development Policy and the implications of any such changes for the future of collections. 2 1 Relationship to other relevant policies/ plans of the organisation: 1.1 The Museum’s statement of purpose is: To collect, safeguard and make accessible artefacts and associated information on the county of Warwickshire for the benefit of the wider community, present and future 1.2 The Governing Body will ensure that both acquisition and disposal are carried out openly and with transparency 1.3 By definition, the Museum has a long-term purpose and holds collections in trust for the benefit of the public in relation to its stated objectives. The Governing Body therefore accepts the principle that sound curatorial reasons must be established before consideration is given to any acquisition to the collection, or the disposal of any items in the Museum’s collection 1.4 Acquisitions outside the current stated Policy will only be made in exceptional circumstances 1.5 The Museum recognises its responsibility, when acquiring additions to its collections, to ensure that care of collections, documentation arrangements and use of collections will meet the requirements of the Museum Accreditation Standard. -

Land and Building Asset Schedule 2018

STRATFORD ON AVON DISTRICT COUNCIL - LAND AND BUILDING ASSETS - JANUARY 2018 Ownership No Address e Property Refere Easting Northing Title: Freehold/Leasehold Property Type User ADMINGTON 1 Land Adj Greenways Admington Shipston-on-Stour Warwickshire 010023753344 420150 246224 FREEHOLD LAND Licence ALCESTER 1 Local Nature Reserve Land Off Ragley Mill Lane Alcester Warwickshire 010023753356 408678 258011 FREEHOLD LAND Leasehold ALCESTER 2 Land At Ropewalk Ropewalk Alcester Warwickshire 010023753357 408820 257636 FREEHOLD LAND Licence Land (2) The Corner St Faiths Road And Off Gunnings Occupied by Local ALCESTER 3 010023753351 409290 257893 FREEHOLD LAND Road Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 4 Bulls Head Yard Public Car Park Bulls Head Yard Alcester Warwickshire 010023389962 408909 257445 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 5 Bleachfield Street Car Park Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753358 408862 257237 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 6 Gunnings Bridge Car Park School Road Alcester Warwickshire 010023753352 409092 257679 LEASEHOLD LAND Authority LAND AND ALCESTER 7 Abbeyfield Society Henley Street Alcester Warwickshire B49 5QY 100070204205 409131 257601 FREEHOLD Leasehold BUILDINGS Kinwarton Farm Road Public Open Space Kinwarton Farm Occupied by Local ALCESTER 8 010023753360 409408 258504 FREEHOLD LAND Road Kinwarton Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 9 Land (2) Bleachfield Street Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753361 408918 256858 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 10 Springfield Road P.O.S. -

29 Merevale Road, Solihull, B92 8La Asking Price of £359,950

29 MEREVALE ROAD, SOLIHULL, B92 8LA ASKING PRICE OF £359,950 Location Solihull is located approximately 9 miles (14.5 km) southeast of Birmingham city centre. Situated in the heart of England, it is considered to be a prosperous and highly sought-after residential area. The town is the administrative centre of the larger Metropolitan Borough of Solihull and has a range of first rate local amenities, including parks, sports and leisure facilities, schools, libraries, and a theatre/arts complex. The pedestrianised shopping centre has a diverse range of high-street shops, boutiques and speciality restaurants, as well as a multi-screen cinema. There are direct commuter train services to Birmingham and London and easy access to the M5, M6, M40 & M42. Birmingham International Airport and Railway Station are approximately 20 minutes drive away, just next to the National Exhibition Centre. Solihull lies at the edge of an extensive green-belt area, providing easy access to the Warwickshire countryside. Extended Semi Detached Residence Three Bedrooms + Family Bathroom/Wc Lounge & Dining Room Large Dining Kitchen Further Scope for Development (STPP) Beautiful Landscaped Rear Garden Garage & Driveway Gas Central Heating An extended beautifully presented three bedroom semi detached residence with further scope for development (STPP) situated in a popular location. The property offers both gas central heating and double glazing. The accommodation briefing comprises; enclosed entrance porch, entrance hall, dining room, lounge, dining kitchen, -

Choice Plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS

home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 3 Home HOME Choice CHOICE .ORG.UK Plus PLUS ‘Working in partnership to offer choice from a range of housing options for people in housing need’ home choice plus:Layout 1 5/1/10 10:26 Page 4 The Home Choice Plus process The Home Choice Plus process 2 What is a ‘bid’? 8 Registering with Home Choice plus 3 How do I bid? 9 How does the banding system work? 4 How will I know if I am successful? 10 How do I find available properties? 7 Contacts 11 What is Home Choice Plus? Home Choice Plus has been designed to improve access to affordable housing. The advantage is that you only register once and the scheme allows you to view and bid on available properties for which you are eligible across all of the districts. Home Choice Plus has been developed by a number of Local Authorities and Housing Associations working in partnership. Home Choice Plus is a way of allocating housing and advertising other housing options across the participating Local Authority areas. (Home Choice Plus will also be used for advertising other housing options such as private rents and intermediate rents). This booklet explains how to look for housing across all of the Districts involved in this scheme. Please see website for further information. Who is eligible to join the Home Choice Plus register? • Some people travelling to the United Kingdom are not entitled to Housing Association accommodation on the basis of their immigration status. • You may be excluded if you have a history of serious rent arrears or anti social behaviour. -

March & April 2016 Magazine

Heart of England U3A Stratford-upon-Avon Website: www.heartofenglandu3a.btck.co.uk Editor: Edwin Lilly Email: edwin [email protected] Issue 12 March & April 2016 Magazine Welcome to the March & April 2016 edition of our Magazine. This issue runs from 1st March to 30th April. Reports include: March Main Meeting—An Introduction to Wine Memory Course in March SNATTs meeting 11th March—Fred Dibnah April Main Meeting—The Sheldon Tapestries SNATTs meeting 8th April—Trip to Birmingham Jew- ellery Quarter Walking Group—April walk around Shipston Last update: 18th April 2016 Canoeing on the River Avon, Stratford-upon-Avon, with the Rowing Club in the background Magazine. 1st March — 30th April 2016 Page No 1 Heart of England U3A Stratford-upon-Avon Website: www.heartofenglandu3a.btck.co.uk March Monthly Meeting The Wonderful World of Wine by Rob Price Rob Price of the Birmingham Wine School gave a Country Production very interesting and informative talk about wine Rank (tonnes) from all around the world. He posed a question “where are the oldest vineyards in the world?”. 1 France 4,293,466 He put forward several countries for our consid- 2 Italy 4,107,370 eration—France, Italy, Germany, USA, Spain, 3 United States 3,217,000 Portugal, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, amongst others. 4 Spain 3,200,000 He then went on to discuss grape varieties and 5 Chile 1,832,000 their influence on taste of the wine. In most 6 China 1,700,000 countries, wine is drunk as part of a meal—it is 7 Argentina 1,498,400 rarely drunk on its own as we do in Britain. -

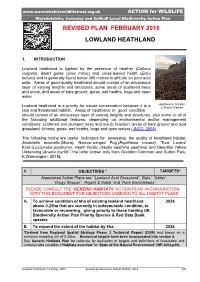

Lowland Heathland 2016.Pdf

www.warwickshirewildlifetrust.org.uk ACTION for WILDLIFE Warwickshire, Coventry and Solihull Local Biodiversity Action Plan REVISED PLAN FEBRUARY 2016 LOWLAND HEATHLAND 1. INTRODUCTION Lowland heathland is typified by the presence of heather (Calluna vulgaris), dwarf gorse (Ulex minor) and cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) and is generally found below 300 metres in altitude on poor acid soils. Areas of good quality heathland should consist of an ericaceous layer of varying heights and structures, some areas of scattered trees and scrub, and areas of bare ground, gorse, wet heaths, bogs and open water. Heathland at Grendon Lowland heathland is a priority for nature conservation because it is a © Steven Cheshire rare and threatened habitat. Areas of heathland in good condition should consist of an ericaceous layer of varying heights and structures, plus some or all of the following additional features, depending on environmental and/or management conditions: scattered and clumped trees and scrub; bracken; areas of bare ground and acid grassland; lichens; gorse; wet heaths, bogs and open waters (JNCC, 2008). The following moths are useful indicators for assessing the quality of heathland habitat: Aristotelia ericinella (Micro), Narrow-winged Pug (Eupithecia nanata), True Lovers’ Knot (Lycophotia porphyria), Heath Rustic (Xestia agathina agathina) and Beautiful Yellow Underwing (Anarta myrtilli ( the latter known only from Grendon Common and Sutton Park, K.Warmington, 2015). 2. OBJECTIVES * TARGETS* Associated Action Plans are: ‘Lowland Acid Grassland’, ‘Bats’, ‘Adder’, ‘Dingy Skipper’, ‘Argent & Sable’ and ‘Rare Bumblebees’ PLEASE CONSULT THE ‘GENERIC HABITATS’ ACTION PLAN IN CONJUNCTION WITH THIS DOCUMENT FOR OBJECTIVES COMMON TO ALL HABITAT PLANS A. To achieve condition of 6ha of existing lowland heathland 2026 above 0.25ha that are currently in unfavourable condition, to favourable or recovering, giving priority to those holding UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority Species & Red Data Book species B. -

Place Based Needs Assessment Rugby Rural North

PLACE BASED NEEDS ASSESSMENT RUGBY RURAL NORTH Warwickshire Joint Strategic Needs Assessment March 2020 REPORT DETAILS Lead Duncan Vernon, Associate Director of Public Health Sponsor(s) Cllr Sally Bragg Insight Analyst/ main author Thomas Kane, Business Intelligence, WCC Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who contributed to the content of this report, including participants of the Steering Group, the stakeholders who attended various community engagement events and those at WCC and externally who have provided data. Date published August 2020 Please note that the research for this report took place prior to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Although the report refers to long standing health and wellbeing issues which have and will continue to impact upon residents, we would encourage you to read them alongside the COVID-19 Health Impact Assessment which is available on the Warwickshire JSNA webpage (from July 2020). This assessment identifies key health and wellbeing indicators that have been affected by the Coronavirus outbreak. The pandemic has, and will continue to have, direct and indirect impacts on individuals and communities across Warwickshire. Some who suffered from COVID- 19 illness are facing a period of recovery of unknown trajectory. Many of those who lost loved ones during the pandemic are having to grieve without having been able to say goodbye, or to be close to others while they grieve. Additionally, economic and mental health impacts are already being felt as a result of the pandemic response, with these impacts disproportionately affecting people from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Groups and those with lower incomes, who have often been at the frontline of the response in essential worker roles. -

Warwickshire

CD Warwickshire 7 PUBLIC TRANSPORT MAP Measham Newton 7 Burgoland 224 Snarestone February 2020 224 No Mans Heath Seckington 224 Newton Regis 7 E A B 786 Austrey Shackerstone 785 Twycross 7 Zoo 786 Bilstone 1 15.16.16A.X16 785 Shuttington 48.X84.158 224 785 Twycross 7 Congerstone 216.224.748 Tamworth 786 Leicester 766.767.785.786 Tamworth Alvecote 785 Warton 65 Glascote Polesworth 158 1 Tamworth 786 Little LEICESTERSHIRELEICESTERSHIRE 48 Leicester Bloxwich North 65 65 65.766.767 7 Hospital 16 748 Warton 16A 766 216 767 Leicester 15 Polesworth Forest East Bloxwich STAFFORDSHIRES T A F F O R D S H I R E 785 X84 Fazeley 766 16.16A 786 Birchmoor 65.748 Sheepy 766.767 Magna Wilnecote 786 41.48 7 Blake Street Dosthill Dordon 766.767 761.766 158 Fosse Park Birch Coppice Ratcliffe Grendon Culey 48 Butlers Lane 216 15 Atherstone 65. X84 16 761 748. 7 68 7 65 Atterton 16A 766.76 61 68 ©P1ndar 15 ©P1ndar 7 ©P1ndar South Walsall Wood 7.65 Dadlington Wigston Middleton Baddesley 761 748 Stoke Four Oaks End .767 Witherley Golding Ensor for details 7 Earl Shilton Narborough 15 in this area Mancetter 7 Baxterley see separate Hurley town centre map 41 68 7 Fenny Drayton Bescot 75 216 Common 228 7 Barwell Stadium 16.16A 65 7.66 66 66 X84 WESTWEST Sutton Coldfield 216 15 Kingsbury 228 68 68 65 Higham- 158 Allen End Hurley 68 65 223 66 MIRA on-the-Hill 48 Bodymoor 15 15 Bentley 41 Ridge Lane 748 Cosby 767 for details in this area see Tame Bridge MIDLANDSMIDLANDS 216 Heath separate town centre map Wishaw Marston Hartshill 66 65. -

Coventry and Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study: Stage 2 Final

Coventry & Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on-Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Stage 2 Final Report for North Warwickshire Borough Council and Stratford-on-Avon District Council Prepared by LUC April 2016 Project Title: Joint Green Belt Study Client: Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on-Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1.0 23rd March Draft Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 2.0 13th April Final Draft Report Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 3.0 18th April Final Report Josh Allen Philip Smith Philip Smith 2016 Last saved: 18/04/2016 16:46 Coventry & Warwickshire Joint Green Belt Study Coventry City Council, North Warwickshire Borough Council, Nuneaton and Bedworth Borough Council, Rugby Borough Council, Stratford-on- Avon District Council and Warwick District Council Stage 2 Final Report for North Warwickshire Borough Council and Stratford-on-Avon District Council Prepared by LUC April 2016 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 London NW1 1JD Mapping -

Worcestershire Has Fluctuated in Size Over the Centuries

HUMAN GENETICS IN WORCESTERSHIRE AND THE SHAKESPEARE COUNTRY I. MORGAN WATKIN County Health Department, Abet ystwyth Received7.x.66 1.INTRODUCTION THEwestern limits of Worcestershire lie about thirty miles to the east of Offa's Dyke—the traditional boundary between England and Wales —yet Evesham in the south-eastern part of the county is described by its abbot in a petition to Thomas Cromwell in as situated within the Principality of Wales. The Star Chamber Proceedings (No. 4) in the reign of Henry VII refer to the bridge of stone at Worcester by which the king's subjects crossed from England into Wales and the demonstrations against the Act of 1430 regulating navigation along the Severn were supported by large numbers of Welshmen living on the right bank of the river in Worcestershire. The object of the investigation is to ascertain whether significant genetic differences exist in the population of Worcestershire and south-western Warwickshire and, in particular, whether the people living west of the Severn are more akin to the Welsh than to the English. The possibility of determining, on genetic grounds, whether the Anglo- Saxon penetration was strongest from the south up the rivers Severn and Avon, or across the watershed from the Trent in the north, or from the east through Oxfordshire and Warwickshire is also explored. 2. THECOUNTY Worcestershirehas fluctuated in size over the centuries and Stratford-on-Avon came for a period under its jurisdiction while Shipston-on-Stour, now a Warwickshire township, remained in one of the detached portions of Worcestershire until the turn of the present century. -

Achieving Social Inclusion in Rugby Borough – the Rural Area

Achieving social inclusion in Rugby Borough – the rural area 2 Achieving social inclusion in Rugby Borough – the rural area Disclaimer This report has been prepared by the Warwickshire Observatory, Warwickshire County Council, with all reasonable skill, care, and diligence. We accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to any third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. Copyright Statement The copyright for this publication rests with Warwickshire County Council. This publication may be downloaded from the Warwickshire County Council and Observatory websites free of charge and may be used for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. The report includes Crown copyright and OS copyright information, used with permission. Any material that is reproduced from this report must be quoted accurately and not used in a misleading context. The copyright must be acknowledged and the title of the publication specified. Publication Date: 19 October 2015 Author: Louise Boffey Telephone: 01926 418066 Email: [email protected] 1 Achieving social inclusion in Rugby Borough – the rural area Contents Page Income and labour market 22 Introduction 3 Isolation 23 Methodology 3 Correlation 25 Key Messages 5 Appendices Analysis by Area 1. Map showing LSOAs in the rural area i Number 1: Church Lawford, Kings Newnham and Long Lawford 8 2. Map showing LSOA boundaries & rank of exclusion ii 3. Full list of rank of LSOAs iii Number 2: Wolvey 9 4. Ranking of the top ten LSOAs, IMD 2010 & 2015 iv Number 3: Long Lawford South 10 5.