Suggestions for Calculating Nest Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

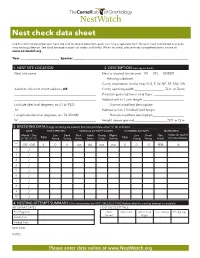

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

Bird Nests What Is a Bird's Nest?

Duke Gardens Winter Fun at Home BIRD NESTS Winter can be a good time to spot bird nests in bare tree branches that lost their leaves in the fall. Have you ever spotted any bird nests or squirrel dreys in a tree? (Drey is the word for a squirrel nest, and they usually look like a messy ball of sticks and leaves). WHAT IS A BIRD’S NEST? All birds start their life cycle as an egg. Eggs need to be protected from weather and predators. An egg also needs to stay warm from the time it is laid until it hatches. This is called the incubation period. A nest is the shelter most adult birds build to protect their eggs until A squirrel drey they hatch and to keep baby birds safe until they are ready to leave (not a bird nest!) the nest. Nests range in size, shape, location and building materials, and all of these can be clues about the kind of bird that made it. For example, bald eagle nests can be 5-6 feet across, while a cardinal’s nest is about 4 inches across. Hummingbird nests can be as small as a thimble when they are built, but they are made with materials that allow the nest to stretch as the baby birds inside it grow. Nests can be built in many places. Some birds make cavity nests inside something by finding or making an opening inside a tree, a stump or a nest box. Carolina wrens, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and some owls are a few examples of cavity nesting birds. -

Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus Carolinensis

eastern gray squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern gray squirrel’s head-body length is Class: Mammalia between eight and 11 inches, with its tail about the Order: Rodentia same length as the body. Its body fur is gray, and there is a border of white fur on the bushy, gray tail. Family: Sciuridae The belly fur is white, a cream line surrounds each ILLINOIS STATUS eye, and white tips are present on the back of the ears. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern gray squirrel may be found statewide in Illinois. It lives in woods or forests that have a closed canopy, nut-bearing trees and plenty of cavity trees. As these mature forests have been destroyed in Illinois, the population of gray squirrels has declined. However, gray squirrels are common in cities. Here, they live in trees without the conditions described above. The gray squirrel eats buds, leaves, fruits, berries, fungi, pecans, acorns, hickory nuts, tree bark, walnuts and the seeds of various other trees. It stores nuts in holes in the ground. This squirrel grasps food in its front paws. It is primarily arboreal, and its large, bushy tail helps it balance while climbing and resting in trees. Urban squirrels are good at climbing brick walls and walking along wires and cables. The eastern gray squirrel does not hibernate and is active during the day year-round. It ILLINOIS RANGE may sleep for several consecutive days in winter, however. Its call is “kuk-kuk-cut-cut-cut.” This animal builds a leaf nest in the high branches of a tree but may use a tree cavity for escape from predators and poor weather and for raising its young. -

Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol

CANADA GOOSE EGG ADDLING PROTOCOL The Humane Society of the United States Wild Neighbors Program 2100 L Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 (202) 452-1100 humanesociety.org/wildlife January 2009 ©The Humane Society of the United States. The HSUS Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol January 2009 Introduction Addling means “loss of development.” It commonly refers to any process by which an egg ceases to be viable. Addling can happen in nature when incubation is interrupted for long enough that eggs cool and embryonic development stops. People addle where they want to manage bird populations. Population management should be only one component of a comprehensive, integrated, humane program to resolve conflict between people and wild Canada geese (see Humanely Resolving Conflicts with Canada Geese: a Guide for Urban and Suburban Property Owners and Communities available online at humanesociety.org/wildlife). A contraceptive drug, nicarbazin sold under the brand name OvoControl (online at ovocontrol.com), reduces hatching to manage populations humanely. Geese who consume an adequate dose during egg production lay infertile eggs. Managing populations with OvoControl requires less labor than addling as you do not have to find and treat individual nests. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has registered this drug in the United States. A U.S Fish and Wildlife Agency (USFWS) permit is required. Potential users should also check to see if their state wildlife agencies require an additional permit. Complete contact information for the supplier is at the end of this Protocol. This Protocol is for Canada geese (Branta canadensis spp.) only. Other species of birds have different nesting chronologies and incubation periods that make appropriate addling different. -

Starlings and Mynas

Beneficial Starlings The Eurasian Rose-colored and African Wattled Starlings are believed Starlings to be beneficial due to their insect con trol near agricultural crops. Both species establish breeding colonies in and Mynas areas where swarms of locusts and by Susan Congdon, grasshoppers appear. It is believed that Disney's Animal Kingdom, FL they eat enough of these insects to protect food crops. banded and released have been sub Pest Starlings? he names starling and myna sequently recovered when found for There are some species of star are often used interchange sale in Indonesian bird markets. The ling/myna that are considered to be T ably similar to pigeoN. and conversion of forest to agricultural pests. The European Starling and dove. Myna is the Hindi word for star land, and deforestation for firewood Common Myna are two examples of ling and is often used for species native and human settlements have greatly this. European Starlings were intro to southern and southeastern Asia and decreased their natural habitat. duced to North America and are the southeastern Pacific. Many of the In response to the decreasing wild extremely gregarious. As well as dam Asian birds are known as both starlings population, the American Zoo and aging important crops they compete and mynas. Aquarium Association, Jersey Wildlife with native birds for hollows in which Preservation Trust, and the Indonesian to nest. Near Extinction ofthe Bali Myna government have set up a Species Common Mynas, introduced to There are 114 species in the Survival Program (SSP). The main goals many places including Hawaii and sturnidae family. -

Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations Cliff swallows present a high degree of intraspecific brood parasitism. Individuals often lay eggs in other individuals’ nests within the same colony. It has been observed that some parasitic swallows have even tossed out their neighbors’ eggs and replaced them with their own offspring. Parasitized swallows had lower success in fledging their own chicks. This behavior has been adapted to increase the parasitic swallow’s offspring’s success by passing on the burden of taking care of chicks to another individual. Solitary Barn swallow at Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS There are eight species of swallows that regularly breed in North America: the Bank swallow, Barn swallow, Cave swallow, Cliff swallow, Northern Rough-winged swallow, Purple martin, Tree swallow, and Violet-green swallow. Natural History: After migrating north from their wintering grounds, mostly in Central America, Cliff and Barn swallows often nest on cliffs, canyons, bridges, and eaves of buildings. Swallows may construct an entirely new Cliff swallows constructing their nests at Kern National nest or they may use old nests, building off of traces Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS of mud where an old nest used to be. The breeding season for swallows lasts from March through Ecological Value of Swallows: September. They often produce two clutches per Swallows provide us with an ecological service as year, with a clutch size of 3-5 eggs. Eggs incubate insect controllers. They particularly consume between 13-17 days and fledge after 18-24 days. swarming insects such as bees, wasps, flies, However, chicks return to the nest after fledging for damselflies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, and several weeks before they leave the nest for good. -

Tree Squirrels There Is Undoubtedly No Other Animal That Has Developed Such a Love-Hate Relationship Around Our Homes and Gardens As That of Tree Squirrels

Tree Squirrels There is undoubtedly no other animal that has developed such a love-hate relationship around our homes and gardens as that of tree squirrels. The eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and fox squirrel (Sciurus niger) are the two species of tree squirrels found in Louisiana. Depending upon your locality, there are two subspecies of gray squirrels and three subspecies of fox squirrels that can be encountered in our state. The nominate race of the eastern gray squirrel occurs in the northwestern por- tion of Louisiana while the darker subspecies know as S. c. fuliginosus occurs in our more southern par- ishes. Throughout the central and northern parishes, specimens tend to show intermediate color charac- teristics between the two subspecies. Eastern gray eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) squirrels regardless of their origin are often referred to as simply gray or cat squirrels. S. n. ludovicianus. These animals are characterized as the largest of all subspecies with a massive skull The three subspecies of fox squirrels found in and slightly paler coloration than the more eastern our state vary drastically in size and color. The subspecies. The bottomland hardwood forests of the western one-third of Louisiana is occupied by Tensas, Mississippi, and Atchafalaya floodplains in the eastern and central-southern portions of the state are home to the smaller, darker subspecies S. n. sub- auratus. Melanistic or black individuals are so com- mon in this subspecies that in local populations, they often outnumber the normal color phase. Areas east of the Mississippi River into the Florida parishes are home to the well-marked race of fox squirrels known as S. -

Use of Materials in Nest Construction by Pied Flycatchers Ficedula Hypoleuca Reflects Localized Habitat and Geographical Location

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Bird Study ISSN: 0006-3657 (Print) 1944-6705 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tbis20 Use of materials in nest construction by Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca reflects localized habitat and geographical location Kevin B. Briggs & D. Charles Deeming To cite this article: Kevin B. Briggs & D. Charles Deeming (2016): Use of materials in nest construction by Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca reflects localized habitat and geographical location, Bird Study To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2016.1238867 Published online: 30 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tbis20 Download by: [University of Lincoln] Date: 30 September 2016, At: 02:34 BIRD STUDY, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2016.1238867 Use of materials in nest construction by Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca reflects localized habitat and geographical location Kevin B. Briggsa and D. Charles Deemingb aIndependent Researcher, Carnforth, Lancashire, UK; bJoseph Banks Laboratories, School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Capsule: Pied Flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca use different materials to construct their nests Received 19 April 2016 according to local availability and geographical location. Accepted 16 September 2016 Aims: This study tested the hypotheses that Pied Flycatcher nests were constructed from the leaves of different tree species in proportion to their occurrence within the breeding territories and that nest composition varied between geographical locations. -

Nesting Ecology and Habitat Use of Chelydra Serpentina in an Area Modified by Agricultural and Industrial Activity

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 12:292–306. Submitted: 18 July 2016; Accepted: 31 March 2017; Published: 30 April 2017. Nesting Ecology and Habitat Use of Chelydra serpentina in an Area Modified by Agricultural and Industrial Activity Molly M. Thompson1, Brittney H. Coe1, Justin D. Congdon2,3, Dean F. Stauffer1, and William A. Hopkins1,4 1Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech, 106 Cheatham Hall, Blacksburg, Virginia 24062, USA 2Savannah River Ecological Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, South Carolina 29802, USA 3Bar Boot Ranch, Box 1128, Douglas, Arizona 85608, USA 4Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Habitat loss and pollution have been linked to declines of numerous freshwater turtle species, which are among the most endangered vertebrates in the world. We examined characteristics of nest sites of Common Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina) located in a system modified by agricultural and industrial land use. We compared characteristics of 150 turtle nests and patterns of nest depredation in mercury (Hg) polluted and reference sites. Of the nests found in this study, 90% were located in human disturbed soils: 79% in agricultural fields and 11% in commercial nurseries. In both Hg and reference sites, we found that 52% of all nests were located in high density nesting areas in agricultural fields bordered by a river on three sides, providing novel evidence that river geomorphology could be useful for identifying important nesting areas. We did not observe predation in the reference sites but 66% of nests were destroyed at the Hg polluted sites. We provide a predictive model demonstrating that the same characteristics influence nest-site selection in this modified system as in more intact systems, and are related to solar exposure at the time of nesting. -

CARPENTER ANTS (Camponotus Sp.)

Dr. Gale E. Ridge Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8600 Fax (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: https://portal.ct.gov/caes CARPENTER ANTS (Camponotus sp.) Carpenter ants specialize in colonizing water- damaged wood (Fig.1). In Connecticut, the three carpenter ant species most likely to establish colonies in buildings are the Eastern black carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus, a smaller species of black carpenter ant Camponotus nearcticus, and the red carpenter ant Camponotus chromaiodes. David Cappaert, Bugwood.org Fig. 2: Black carpenter ant worker The red carpenter ant C. chromaiodes is between these two in size. Workers are about 1/4 - 1/3” long, and have a reddish-brown thorax. Sharon Lilly, International Society of Arboriculture, Bugwood.org Fig. 1: Carpenter ant colony in wooden beam Jon Yuschock, Bugwood.org Description: The Eastern black carpenter ant Fig. 3: Carpenter ant reproductive ‘swarmer’ (C. pennsylvanicus) is one of the largest ants in New England. It is the most common Ant reproductives are larger than workers, building infesting ant. Workers range in size winged and are known as “alates” or from ¼ to ½” in length (Fig. 2), while the “swarmers.” These ants are males and winged reproductive adults range in size unmated queens, who leave the nest, mate, from 1/2 to 3/4” (Fig. 3). Camponotus and disperse to establish new colonies. nearcticus is much smaller than C. pennsylvanicus and is not as common. -

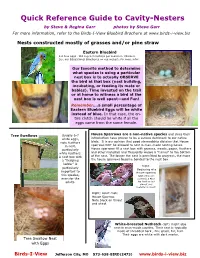

Quick Reference Guide to Cavity-Nesters by Steve & Regina Garr Photos by Steve Garr

Quick Reference Guide to Cavity-Nesters by Steve & Regina Garr photos by Steve Garr For more information, refer to the Birds-I-View Bluebird Brochure at www.birds-i-view.biz Nests constructed mostly of grasses and/or pine straw Eastern Bluebird 4-6 blue eggs . Will avg 2-3 nestings per season in Missouri. See our Educational Brochures on our website for more info! Our favorite method to determine what species is using a particular nest box is to actually OBSERVE the bird at that box (nest building, incubating, or feeding its mate or babies). Time invested on the trail or at home to witness a bird at the nest box is well spent—and Fun! Remember….a small percentage of Eastern Bluebird Eggs will be white instead of blue. In that case, the en- tire clutch should be white if all the eggs came from the same female. Tree Swallows Usually 6-7 House Sparrows are a non-native species and since their white eggs, introduction have proven to be a serious detriment to our native note feathers birds. It is our opinion that good stewardship dictates that House in nest, sparrows NOT be allowed to nest in man-made nesting boxes. particularly House sparrows fill a nest box with grasses, weeds, paper, feathers white feathers. and other materials and frequently weave a “tunnel” to the bottom A nest box with of the nest. The longer the nest is permitted to progress, the more a “fledgling the house sparrows become bonded to the nest box. ladder” is Right: particularly Beginning of a important to House sparrow this species, nest (this one even for the contains a Blue adults. -

Nest Site Characteristics and Breeding Biology of Flammmulated Owls in Missoula Valley

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2011 Nest Site Characteristics and Breeding Biology of Flammmulated Owls in Missoula Valley Mathew T. Seidensticker The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Seidensticker, Mathew T., "Nest Site Characteristics and Breeding Biology of Flammmulated Owls in Missoula Valley" (2011). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 698. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/698 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS AND BREEDING BIOLOGY OF FLAMMULATED OWLS (Otus flammeolus) IN MISSOULA VALLEY By MATHEW THOMAS SEIDENSTICKER BS, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, 2000 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Studies The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2011 Approved by: J.B. Alexander Ross, Associate Dean for Graduate Education Graduate School Len Broberg, Chair Environmental Studies Dick Hutto Divison Biological Sciences Dave Pattersen Math Department Denver Holt Owl Research Institute Seidensticker, Mathew, M.S., Spring 2011 Environmental Studies Nest Sites and Breeding Biology of Flammulated Owls in Missoula Valley Chairperson: Len Broberg The Flammulated Owl is listed as a sensitive or species of concern with United States Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.