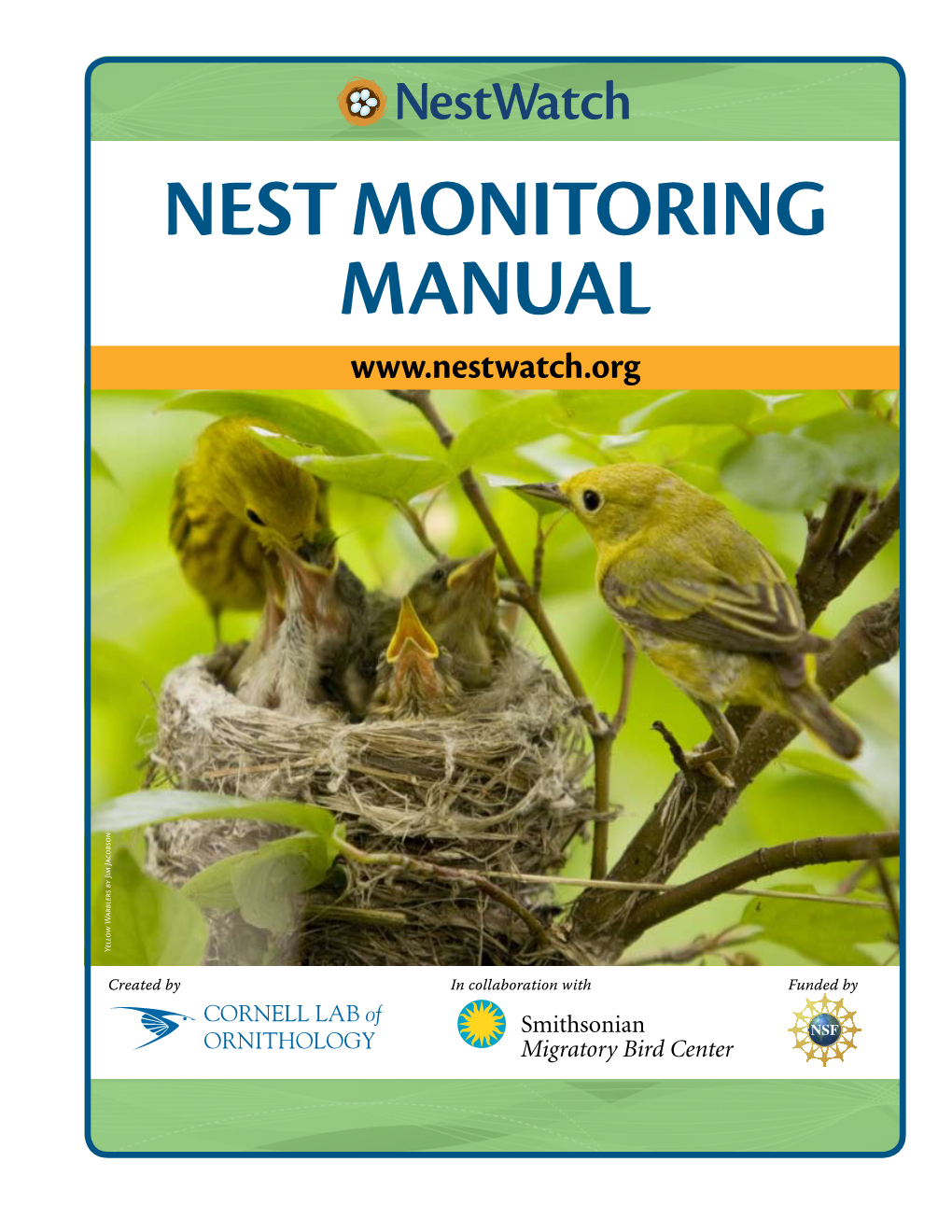

Nest Monitoring Manual Yellow Warblers by Jim Jacobson Jim by Warblers Yellow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

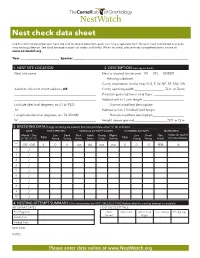

Nest Check Data Sheet

Nest check data sheet Use this form to describe your nest site and to record data from each visit. Use a separate form for each nest monitored and each new nesting attempt. See back for explanations of codes and fields. When finished, please enter completed forms online at: www.nestwatch.org. Year _________________________ Species ______________________________________________________________________________ 1. NEST SITE LOCATION 2. DESCRIPTION (see key on back) Nest site name Nest is located (circle one) IN ON UNDER __________________________________________________ Nesting substrate _______________________________ Cavity orientation (circle one) N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, SW Address: Nearest street address OR Cavity opening width __________________ ❏ in. or ❏ cm __________________________________________________ Predator guard ❏ None or ❏ Type: __________________ __________________________________________________ Habitat within 1 arm length _________________________ Latitude (decimal degrees; ex 47.67932) Human modified description ___________________ N _______________________________________________ Habitat within 1 football field length _________________ Longitude (decimal degrees; ex -76.45448) Human modified description ___________________ W _______________________________________________ Height above ground ____________________❏ ft. or ❏ m 3. BREEDING DATA If eggs or young are present but not countable, enter “u” for unknown. DATE HOST SPECIES STATUS & ACTIVITY CODES COWBIRD ACTIVITY MORE INFO Month / Day Live Dead Nest Adult Young -

Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement

PROTECTING NESTING BIRDS BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR VEGETATION AND CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS Version 3.0 May 2017 1 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 2.0 BIRDS IN PORTLAND 4 3.0 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF PORTLAND BIRDS 4 3.1 Timing 4 3.2 Nesting Habitats 5 4.0 GENERAL GUIDELINES 9 4.1 What if Work Must Occur During Avoidance Periods? 10 4.2 Who Conducts a Nesting Bird Survey? 10 5.0 SPECIFIC GUIDELINES 10 5.1 Stream Enhancement Construction Projects 10 5.2 Invasive Species Management 10 - Blackberry - Clematis - Garlic Mustard - Hawthorne - Holly and Laurel - Ivy: Ground Ivy - Ivy: Tree Ivy - Knapweed, Tansy and Thistle - Knotweed - Purple Loosestrife - Reed Canarygrass - Yellow Flag Iris 5.3 Other Vegetation Management 14 - Live Tree Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Snag Removal - Shrub Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Grassland Mowing and Ground Cover Removal (Native and Non-Native) - Controlled Burn 5.4 Other Management Activities 16 - Removing Structures - Manipulating Water Levels 6.0 SENSITIVE AREAS 17 7.0 SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 17 7.1 Species 17 7.2 Other Things to Keep in Mind 19 Best Management Practices: Avoiding Impacts on Nesting Birds Version 3.0 –May 2017 2 8.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND AN ACTIVE NEST ON A PROJECT SITE 19 DURING PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION? 9.0 WHAT IF YOU FIND A BABY BIRD OUT OF ITS NEST? 19 10.0 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS FOR AVOIDING 20 IMPACTS ON NESTING BIRDS DURING CONSTRUCTION AND REVEGETATION PROJECTS APPENDICES A—Average Arrival Dates for Birds in the Portland Metro Area 21 B—Nesting Birds by Habitat in Portland 22 C—Bird Nesting Season and Work Windows 25 D—Nest Buffer Best Management Practices: 26 Protocol for Bird Nest Surveys, Buffers and Monitoring E—Vegetation and Other Management Recommendations 38 F—Special Status Bird Species Most Closely Associated with Special 45 Status Habitats G— If You Find a Baby Bird Out of its Nest on a Project Site 48 H—Additional Things You Can Do To Help Native Birds 49 FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1. -

12(3) Island Representative Reports—St

ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE REPORTS— DOMINICA lands are expected to be included as part of the Wren Troglodytes aedon, Broad Wing Hawk Buteo Morne Diablotin National Park. platypterus, and Bananaquit Coereba flaveola). BIRD NEST MONITORING OTHER ACTITIES Bird nest monitoring was conducted by Benito • Overseas visit – November 1998, Trinidad – Espinal and Bertrand Jno Baptiste, who expect to FAO Workshop on Management of wild bird publish their data later this year. This research activ- population in the West Indies. ity has resulted in an exciting discovery for Domin- • ica; i.e., it has been confirmed that the Bare-eyed Training for Tour Guides in Fauna and Flora of Thrush (Turdus nidigenis) is a resident breeder in an Dominica. area known as Pentiwax. This study also confirmed • Participation in International Migratory Bird that both the Bare-eyed Thrush and the Red-legged Day and World Birdwatch Day. Thrush (Turdus plumbeus) are using soil in the con- • Search for Bare-eyed Thrush in several habitats struction of their nest. Several other bird nests were around the island. observed (including Barn Owl Tyto alba, House ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE REPORT ST. LUCIA DONALD ANTHONY ISLAND REPRESENTATIVE—ST. LUCIA Forestry Department, Ministry of Agriculture, Castries, St. Lucia This report is a summary of the main activities Three tree top observation platforms were replaced in within the Wildlife Section of the Forestry Depart- Quilesse. They had been in place since September ment in St. Lucia from August 1998 to July 1999. 1994, but succumbed to the elements in the forest ca- nopy. PARROT PROJECT For the first time ever the fully decomposed re- mains of an adult parrot were found in the wild. -

Bird Nest Protection During Construction & Tree/Shrub Trimming

Bird Nest Protection During Construction & Tree/Shrub Trimming Did you know? How Can You Avoid Nesting Birds During TO HARM OR HARASS A NATIVE BIRD OR ITS Construction & Tree/Shrub Trimming? NEST IS A VIOLATION OF FEDERAL AND STATE LAW ⇒ Conduct brush removal, tree trimming, building demolition, or grading activities outside of the nesting season. The raptor breeding season begins January 1st and ends September 30th and the nesting season for other birds on the Palos Verdes Peninsula is February 15th through August 31st. In planning your project or foliage trimming, consider hiring a biologist to survey the project site to determine if or when it is safe to commence construction or trimming activities. Depending on the size of the project area, a professional survey may only take an hour. ⇒ If other timing restrictions make it impossible to avoid the nesting season, the construction area or nearby shrubs/trees should be surveyed for nesting birds. Active nests should be State & Federal Laws avoided as described below: Protect ALL Native Birds Inspect the project site for nests. If birds are observed The Migratory Bird Treaty Act flying to and from a nearby nest, or sitting on a nest, it can (MBTA) is one of the nation’s oldest be assumed that the nest is active. Construction activity or environmental laws passed in 1918. tree trimming should then be delayed until a qualified Under the provisions of the MBTA, it biologist could conduct a nesting survey and provide you is unlawful “by any means or manner with further guidance. Do not disturb or remove the active to pursue, hunt, take, capture (or) kill” nest! It is better to be take these precautionary measures, any migratory birds except as than to run afoul of the law and be subject to fines and permitted by regulations issued by the criminal penalties. -

Bird Nests What Is a Bird's Nest?

Duke Gardens Winter Fun at Home BIRD NESTS Winter can be a good time to spot bird nests in bare tree branches that lost their leaves in the fall. Have you ever spotted any bird nests or squirrel dreys in a tree? (Drey is the word for a squirrel nest, and they usually look like a messy ball of sticks and leaves). WHAT IS A BIRD’S NEST? All birds start their life cycle as an egg. Eggs need to be protected from weather and predators. An egg also needs to stay warm from the time it is laid until it hatches. This is called the incubation period. A nest is the shelter most adult birds build to protect their eggs until A squirrel drey they hatch and to keep baby birds safe until they are ready to leave (not a bird nest!) the nest. Nests range in size, shape, location and building materials, and all of these can be clues about the kind of bird that made it. For example, bald eagle nests can be 5-6 feet across, while a cardinal’s nest is about 4 inches across. Hummingbird nests can be as small as a thimble when they are built, but they are made with materials that allow the nest to stretch as the baby birds inside it grow. Nests can be built in many places. Some birds make cavity nests inside something by finding or making an opening inside a tree, a stump or a nest box. Carolina wrens, chickadees, nuthatches, woodpeckers, and some owls are a few examples of cavity nesting birds. -

Eastern Gray Squirrel Sciurus Carolinensis

eastern gray squirrel Sciurus carolinensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern gray squirrel’s head-body length is Class: Mammalia between eight and 11 inches, with its tail about the Order: Rodentia same length as the body. Its body fur is gray, and there is a border of white fur on the bushy, gray tail. Family: Sciuridae The belly fur is white, a cream line surrounds each ILLINOIS STATUS eye, and white tips are present on the back of the ears. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern gray squirrel may be found statewide in Illinois. It lives in woods or forests that have a closed canopy, nut-bearing trees and plenty of cavity trees. As these mature forests have been destroyed in Illinois, the population of gray squirrels has declined. However, gray squirrels are common in cities. Here, they live in trees without the conditions described above. The gray squirrel eats buds, leaves, fruits, berries, fungi, pecans, acorns, hickory nuts, tree bark, walnuts and the seeds of various other trees. It stores nuts in holes in the ground. This squirrel grasps food in its front paws. It is primarily arboreal, and its large, bushy tail helps it balance while climbing and resting in trees. Urban squirrels are good at climbing brick walls and walking along wires and cables. The eastern gray squirrel does not hibernate and is active during the day year-round. It ILLINOIS RANGE may sleep for several consecutive days in winter, however. Its call is “kuk-kuk-cut-cut-cut.” This animal builds a leaf nest in the high branches of a tree but may use a tree cavity for escape from predators and poor weather and for raising its young. -

Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol

CANADA GOOSE EGG ADDLING PROTOCOL The Humane Society of the United States Wild Neighbors Program 2100 L Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 (202) 452-1100 humanesociety.org/wildlife January 2009 ©The Humane Society of the United States. The HSUS Canada Goose Egg Addling Protocol January 2009 Introduction Addling means “loss of development.” It commonly refers to any process by which an egg ceases to be viable. Addling can happen in nature when incubation is interrupted for long enough that eggs cool and embryonic development stops. People addle where they want to manage bird populations. Population management should be only one component of a comprehensive, integrated, humane program to resolve conflict between people and wild Canada geese (see Humanely Resolving Conflicts with Canada Geese: a Guide for Urban and Suburban Property Owners and Communities available online at humanesociety.org/wildlife). A contraceptive drug, nicarbazin sold under the brand name OvoControl (online at ovocontrol.com), reduces hatching to manage populations humanely. Geese who consume an adequate dose during egg production lay infertile eggs. Managing populations with OvoControl requires less labor than addling as you do not have to find and treat individual nests. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has registered this drug in the United States. A U.S Fish and Wildlife Agency (USFWS) permit is required. Potential users should also check to see if their state wildlife agencies require an additional permit. Complete contact information for the supplier is at the end of this Protocol. This Protocol is for Canada geese (Branta canadensis spp.) only. Other species of birds have different nesting chronologies and incubation periods that make appropriate addling different. -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

Starlings and Mynas

Beneficial Starlings The Eurasian Rose-colored and African Wattled Starlings are believed Starlings to be beneficial due to their insect con trol near agricultural crops. Both species establish breeding colonies in and Mynas areas where swarms of locusts and by Susan Congdon, grasshoppers appear. It is believed that Disney's Animal Kingdom, FL they eat enough of these insects to protect food crops. banded and released have been sub Pest Starlings? he names starling and myna sequently recovered when found for There are some species of star are often used interchange sale in Indonesian bird markets. The ling/myna that are considered to be T ably similar to pigeoN. and conversion of forest to agricultural pests. The European Starling and dove. Myna is the Hindi word for star land, and deforestation for firewood Common Myna are two examples of ling and is often used for species native and human settlements have greatly this. European Starlings were intro to southern and southeastern Asia and decreased their natural habitat. duced to North America and are the southeastern Pacific. Many of the In response to the decreasing wild extremely gregarious. As well as dam Asian birds are known as both starlings population, the American Zoo and aging important crops they compete and mynas. Aquarium Association, Jersey Wildlife with native birds for hollows in which Preservation Trust, and the Indonesian to nest. Near Extinction ofthe Bali Myna government have set up a Species Common Mynas, introduced to There are 114 species in the Survival Program (SSP). The main goals many places including Hawaii and sturnidae family. -

Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Swallows Nesting in Nuisance Locations Cliff swallows present a high degree of intraspecific brood parasitism. Individuals often lay eggs in other individuals’ nests within the same colony. It has been observed that some parasitic swallows have even tossed out their neighbors’ eggs and replaced them with their own offspring. Parasitized swallows had lower success in fledging their own chicks. This behavior has been adapted to increase the parasitic swallow’s offspring’s success by passing on the burden of taking care of chicks to another individual. Solitary Barn swallow at Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS There are eight species of swallows that regularly breed in North America: the Bank swallow, Barn swallow, Cave swallow, Cliff swallow, Northern Rough-winged swallow, Purple martin, Tree swallow, and Violet-green swallow. Natural History: After migrating north from their wintering grounds, mostly in Central America, Cliff and Barn swallows often nest on cliffs, canyons, bridges, and eaves of buildings. Swallows may construct an entirely new Cliff swallows constructing their nests at Kern National nest or they may use old nests, building off of traces Wildlife Refuge. Tim Ludwick/USFWS of mud where an old nest used to be. The breeding season for swallows lasts from March through Ecological Value of Swallows: September. They often produce two clutches per Swallows provide us with an ecological service as year, with a clutch size of 3-5 eggs. Eggs incubate insect controllers. They particularly consume between 13-17 days and fledge after 18-24 days. swarming insects such as bees, wasps, flies, However, chicks return to the nest after fledging for damselflies, moths, grasshoppers, crickets, and several weeks before they leave the nest for good. -

Puffins and Seabirds

PUFFINS AND SEABIRDS GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS INTRODUCTION www.climateclassroom.org/kids ABOUT THIS GUIDE: News about climate change is everywhere—in the newspaper, on TV and the radio, even at the movies. It’s hard enough for This guide’s activities are designed grown-ups to sort out what’s true and to determine what we for grades 3-5, with extensions for should do about it. For kids, it can seem even more compli- younger and older children. These cated and scary. That’s why age appropriateness is a vitally activities meet national standards important ingredient of climate change education. for English/Language Arts, Science, The most age-appropriate measure you can take as a teacher Social Studies, and Visual Arts. is to help your students explore nature in their own neigh- borhoods and communities. This fosters a strong, positive connection with the natural world and builds a foundation for caring about global environmental problems later in life. But how do you answer the questions your students inevi- tably raise about climate change? And how do you begin to examine the topic in a manner that doesn’t frighten or Table of ConTenTs overwhelm them? The best strategy is to provide children with brief, accurate information at a level you know they can understand and relate to—and in hopeful ways. This guide is Climate Change .............................................. 3 one tool you can use to do just that. Activity One: Where in the World .......... 5 Activity Two: Fill the Bill .............................. 8 About Howard Ruby, the photographer: Activity Three: House Hunting ................12 Wildlife images featured on Climateclassroomkids.org and throughout this guide were taken by Howard Ruby. -

MIGRATORY BIRD TREATY ACT Pharr District

MIGRATORY BIRD TREATY ACT Pharr District Footer Text Date Table of contents 1 Pre Construction Meeting 3 2 MBTA Educational Flyer 4 3 MBTA Surveys 5 4 Standard Plan Sheets 7 5 Working with Construction Crews 13 6 7 Footer Text Date 2 Pre Construction Meeting . Pharr District Environmental Staff attends all pre construction meetings – Go over the SW3P, EPIC, ESA, MBTA, Permits, licenses, etc. MBTA surveys must be completed prior to any clearing of any vegetation – Reminder there are ground nesting birds, birds that nest is structures, as well as tree nesting birds – Once the survey is completed, if not cleared, survey must be completed again in ~14 days – If nests are present the survey team will mark the area and we will re check the nests to determine nest status in ~ 14 days to let the construction team know if the chicks have fledged. Footer Text Date 3 MBTA Educational Flyer . Developed MBTA education flyer . Which answers the 7 Questions below: – What is the Migratory Bird Treaty Act? – What does the Act provide? – What is a Migratory Bird? – What is TxDOT’s Role in protecting Migratory Birds? – What are the Penalties for Violations of the Act? – What are the TxDOT projects that have the most potential to harm Migratory Birds? – How can TxDOT avoid harming Migratory Birds and violations of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act? – Who should I contact in the Environmental Section to determine if Migratory Birds may be an issue on the Project? Footer Text Date 4 MBTA FORM Pharr District created a MBTA Survey form to complete during the surveys MIGRATORY BIRD NEST SURVEY FORM (February 15 to October 1) CSJ: HIGHWAY: COUNTY: LIMITS: AREA OFFICE: MAINTENANCE SECTION: Will this project require a migratory bird survey? No Yes If No, state reason(s) why: If Migratory Bird Survey is necessary, has it been conducted: Yes No If yes state: DATE/TIME OF SURVEY: WEATHER: Clear sunny sky.