Creating Sustainable Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012-2017: Metro North East

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Metro North East Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage. Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Metro North East Region Metropolitan and Mountains Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage PO Box 3031 Asquith NSW 2077 Phone: (02) 9457 8900 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 625 3 OEH 2012/0374 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Metro North East Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

NOTICE PAPER ( No

5307 2004-2005-2006-2007 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NOTICE PAPER (www.aph.gov.au/house/info/notpaper) No. 182 TUESDAY, 7 AUGUST 2007 The House meets at 2 p.m. GOVERNMENT BUSINESS Notice *1 MR ABBOTT: To move—That so much of the standing and sessional orders be suspended as would prevent the routine of business for this sitting being as set out in the document presented to the House this day by the Leader of the House. Orders of the day 1 AUSTRALIAN CITIZENSHIP AMENDMENT (CITIZENSHIP TESTING) BILL 2007 (from Senate)(Minister for Immigration and Citizenship): Second reading—Resumption of debate (from 21 June 2007) on the motion of Mr Andrews—That the Bill be now read a second time—And on the amendment moved thereto by Mr A. S. Burke, viz.—That all words after “That” be omitted with a view to substituting the following words: “whilst not declining to give the bill a second reading and whilst welcoming the formalising of the current test for Australian Citizenship, the House: (1) notes that the issue is whether the citizenship tests to be determined under the legislation are reasonable; (2) notes the importance of teaching in the development of English language skills and the acquisition of knowledge of Australian history, culture and values; and (3) calls on the Government to provide improvements to the Adult Migrant English Program and other settlement services to assist migrants to participate fully in the Australian community and to pass the citizenship test”. 2 TRADE PRACTICES LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL (NO. -

Anzac Parade Light Rail Needs Your Support! Light (Rail) Relief for Eastern Sydney Harbour PLANS for a Light Rail Link to the Eastern Suburbs Are Again Under Threat

Hell on Wheels TRANSPORT & LIFESTYLE SOLUTIONS FOR SYDNEY No.8 • October 2002 E A S T E R N S U B U R B S T R A N S P O R T U P D A T E Buses not big enough to cope with demand for public transport Campaign to save Anzac Parade light rail needs your support! Light (rail) relief for Eastern Sydney Harbour PLANS for a light rail link to the eastern suburbs are again under threat. Residents of Kensington and Randwick—one of the densest Suburbs Proposed urban areas in Australia—are crying out for better public transport. city light rail loop But Randwick Council still isn’t listening. commuters extension Incredibly, the Council wants to modern trams can make a fast run IN NOVEMBER 2000 EcoTransit Oxford Street cafes remove the median strip along down Anzac Parade. and nightclubs Anzac Parade in Kensington, Good fortune has preserved Sydney, with the help of Clover threatening the crucial light-rail much of the route needed for an Moore, the independent member Paddington corridor. eastern suburbs light rail link, but for Bligh, launched a light rail proposal called the Bay Light Sydney Cricket The last ten years has seen a it is now seriously threatened! In Ground boom in high density residential a recent leaflet sent to local Express. Since then the Bay Light residents, Council complained has enjoyed wide popular support! developments around the Fox Studios University of New South Wales. that Anzac Parade has a ‘freeway Stage One of this is called the More flats means more people, feel’ due to high volumes of road Bay Light East. -

The Randwick City Plan

The Randwick City Plan A 20 year Plan DRAFT Sydney Harbour Circular Quay Wynyard St James Kings Cross The SYDNEY CENTRE Edgecliff Central Randwick Bondi Junction Redfern City Plan Bondi Beach Macdonaldtown Moore Park Newtown Erskineville Centennial Park Av themes oca Green Square Dr St Ar oss St Peters den Messages 4 KensingtonCr n Aliso n Rd St Introduction 6 Randwick Clovelly Bay About Randwick City 7 UNSW Coogee Coogee Souther Ba Gordons Bay Randwick y Rd Our local area 8 Hospitals Mascot Kingsford The Spot Coogee Beach About the plan 9 complex Bunner Anzac Measuring success 10 Our City and Pd Our city and e Engaging with the community 11 Surrounds ong Demographics 16 surrounds Rd Maroubra Lurline Bay State and regional influences 18 Regional context Junction Guiding principals 19 Eastgardens Mar Randwick City oubra SYDNEY Rd DRAFT Av DRAFTThemes and outcomes 20 Centennial Park, Heffron Park AIRPORT Fitzgerald and Botany Bay National Park Responsible management 20 Heffron Rd Maroubra Beach Port and port-related land Park Beauchamp A sense of community 28 Commercial centre Places for people 40 A prospering City 56 Adjacent recreation facilities Foreshor Matraville e Rd Botany Moving around 62 Adjacent major centres Rd Malabar Looking after our environment 70 Long Bay 0 300m 1.2km Our City – a closer look 80 PORT BOTANY Our finances – a closer look 78 Yarra Bay Little Bay La Perouse Frenchmans Bay Congwong Botany Bay Bay National Park Botany Bay Cape Banks 3 © Randwick City Council Mayor’s message General Manager’s message Our City Plan, first developed The Randwick City Plan in 2006 in close consultation provides the long-term with the community, is a 20- vision and directions for year guide for planning for a practical approach to our City’s future. -

Randwick Local Strategic Planning Statement (LSPS)

Local Strategic Planning Statement Randwick City Council 1300 722 542 randwick.nsw.gov.au March 2020 Randwick City Council 1300 722 542 Follow us here 30 Frances Street [email protected] Randwick NSW 2031 www.randwick.nsw.gov.au 2 Randwick City Council Contents Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander statement 4 About the Local Strategic Planning Statement 5 Our Vision 11 Context 12 Structure Plan 18 Randwick City Planning Priorities 21 Liveability 24 Productivity 36 Sustainability 48 Infrastructure and Collaboration 63 Implementation Plan 67 Local Strategic Planning Statement 3 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander statement Randwick City Council acknowledges that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the First Australians of this land, and the Bidjigal and Gadigal people who traditionally occupied the land we now call Randwick City. Randwick City has a rich and unique Aboriginal cultural history, with La Perouse being the only area in Sydney where the local Aboriginal community have had an unbroken connection to the land. We recognise and celebrate the spiritual and cultural connection Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have with the land which long pre-dates European settlement and continues today. Building on our Statement of Recognition and commitment to Reconciliation, Council wishes to support the vision and plans of our local Aboriginal and Torres Strait community in order to close the gap on disadvantage, build stronger local and regional economies and support culturally rich and healthy communities. -

Botany Bay National Park

BOTANY BAY NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service May 2002 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 27th May 2002. Cover photograph: View from the southern (Kurnell) headland of Botany Bay National Park looking towards the northern (La Perouse) headland, by Mike Cufer. Crown Copyright 2002: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. ISBN 0 7313 6355 8 FOREWORD Botany Bay National Park is highly significant to all Australians because it includes the site of first contact in 1770 between indigenous Australians and the crew of Lieutenant James Cook’s Endeavour and may be seen as a symbolic meeting place of cultures. It is also the place of last sighting of the French explorer Compte de Laperouse in 1788, the type locality for many of the plant species first collected by Banks and Solander, and contains an important samples of endangered ecological communities. The park’s scenic values have been recognised by the National Trust in classifying it as a landscape conservation area, and it contains a number of historic places of national significance. The remaining Aboriginal sites are important evidence of the long association of Aboriginal people with the area. Inherent in the landscape of Botany Bay National Park is the long history of changing ecosystems and developing cultures. The role of Botany Bay National Park as a ‘meeting place’ is a central theme for the park. The park offers a unique opportunity to explore the history of meetings between indigenous and other cultures in Australia. The plan provides for the protection, and where necessary rehabilitation, of the landscapes, ecosystems, vegetation communities, fauna and faunal habitats of the park. -

Pterostylis Sp. 15 (Orchidaceae) Botany Bay Bearded Greenhood Orchid

Draft Recovery Plan Pterostylis sp. 15 (Orchidaceae) Botany Bay Bearded Greenhood Orchid Draft for public exhibition September 2000 © NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, 2000. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from NPWS. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service 43 Bridge Street (PO Box 1967) Hurstville NSW 2220 Tel: 02 9585 6444 www.npws.nsw.gov.au For further information contact Threatened Species Unit, Central Directorate. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service P.O. Box 1967 Hurstville NSW 2220 Tel 02 9585 6678 Cover illustration: Pterostylis sp. 15 Cover illustrator: John Riley This plan should be cited as following National Parks and Wildlife Service (2000) Pterostylis sp. 15 Botany Bay Bearded Greenhood Orchid Draft Recovery Plan. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Hurstville. ISBN - 0731361962 2 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Recovery Planning Program Pterostylis sp. 15 (Orchidaceae) Botany Bay Bearded Greenhood Draft Recovery Plan Prepared in accordance with the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 and the Commonwealth Endangered Species Protection Act 1992. September 2000 Acknowledgments The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service would like to thank the following: Gary Dunnet, Nicole Davis and Georgina Eldershaw (NPWS) for on going management of the habitat of P. sp. 15 and involvement in the preparation of this plan. Graeme Bradburn, John Riley, Bill Brinsley, Margaret Bradhurst and John Kellar who shared local knowledge and information about the species and participated in the field work during 1998 and 1999. John Riley for the use of his drawings of P. -

AT SYDNEY's MALABAR HEADLAND Introduction

Chapter 1 PLANNING FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: ‘WICKED PROBLEMS’ AT SYDNEY’S MALABAR HEADLAND Krishna K. Shrestha and John Dee Planning decisions about sustainable development are often confronted with multiple and at times incommensurable interest sets that do not lend themselves to straightforward solutions through the application of scientific methods of rational planning theories. Rittel and Weber coined the term ‘wicked problems’ to describe this phenomenon. This chapter explores a set of wicked problems in the Malabar Headland in Sydney, Australia. By employing a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods, it was found that wicked problems were produced, reproduced and perpetuated in the Malabar Headland due mainly to two principal reasons: a) operational – relating to the complex and conflicting value- sets among stakeholders and multiple uses; and b) structural – relating to the institutional and interest group politics inherent within the layered federal system of government in Australia. As a result, the planning systems were unable to deliver decisions consistent with overarching environmental and social policy imperatives. The end result was a monumental planning stalemate. The chapter concludes by reflecting on the empirical findings of the Malabar case in relation to relevant theories of planning to gain an understanding of how planning systems can deliver outcomes that meet both environmental and social imperatives for sustainable development. Introduction Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’, the Club of Rome’s ‘The Limits to Growth’, Schumacher’s ‘Small is Beautiful’ and Brundtland’s ‘Our Common Future’ have all in different ways focused on conserving and protecting environmental values in the face of unprecedented growth. It was the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987) that popularised the concept of sustainable development in both academic and policy vocabulary, and in 3 the political mainstream. -

1. Walks/Activities 2. Malabar Headland National Park 3. Vale

PRINT POSTAGE POST PAID 100003282 AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER NATIONAL PARKS ASSOCIATION OF NSW INC Autumn edition 121 2018 SOUTHERN SYDNEY BRANCH If undeliverable return to: PO Box 269, Engadine, NSW 2233 PRESIDENT: Brian Everingham BUSINESS MEETINGS All are welcome to attend, SECRETARY: Gary Schoer have your say and hear what’s happening in the NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Brian Everingham NPA. Contact Peter on 95287341 or Gary on phone/fax 95209341 95701813 for details. These meetings are now held Send copy to [email protected] on either the 1st or 2nd Wednesdays of the month, ISSUE: 121.2 except when this coincides with school holidays BRANCH MEETINGS: Come and meet other members from your local area, new members and friends are most welcome. These meetings are organised for you, are informal, informative and In This Issue: relaxing. An interesting evening is guaranteed and supper is provided. The venue for Branch meetings is the Multi-Purpose Centre, 123 Flora St Sutherland 1. Walks/Activities (near Belmont St) 3 minutes’ walk from the railway 2. Malabar Headland National Park station and with plenty of parking. All meetings 3. Vale Bob Walshe commence at 8.00pm. Now held on the 4th 4. Spring Gully Wednesday night every second month, depending on public holidays. The next meeting is April 18th 1 | P a g e Our Branch The NPA offers members over 1000 free midweek and weekend activities a year including bush walks, canoe trips, bike rides, biodiversity surveys, bird watching, and family trips. Activities cater for all levels of fitness. Easy/short walks, day bushwalks, overnight bushwalks, week bushwalks, educational walks, Walks/Activities Branch Talks (contact Peter Vaughan for details, at [email protected] ) 18 Apr Citizen Science underwater and the case for a Sydney-wide marine park The waters around Sydney are world renowned for their natural beauty, almost 600 fish species have been recorded in Sydney. -

Draft Eastern District Plan

Draft Eastern District Plan Submission_id: 31716 Date of Lodgment: 15 Dec 2017 Origin of Submission: Online Organisation name: Friends of Malabar Headland Organisation type: Community Group First name: N/A Last name: N/A Suburb: 2035 Submission content: see attached pdf document Number of attachments: 1 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) GSC submission by FoMH – Eastern City 15-12-2017 Thank you for the opportunity to comment and make a submission. Friends of Malabar Headland members (FoMH) live in the Eastern City region of the Greater Sydney Region plan, at Maroubra and Malabar and surrounding suburbs. Our area is liveable, and probably could be called a “30 minute city” already. Most people can walk or cycle to the nearest shops, the library, the cinema, schools, the beach, etc, within 30 minutes. Our suburbs are pleasant, with wide streets and ample car parking (so far), many houses have gardens, and we have some street trees, although not as many as on the North Shore of Sydney due to the sandy nature of the soil. Street trees have to be tough here. FoMH wants to make some general and specific comments about the GSC plans for our area. General: We are interested in planning, but we found it hard to have a great deal of input to the GSC before the plans were produced. There is a problem of communication: 99 people out of 100 have no idea that the GSC exists, or that it might affect their lives. This is still the case. The GSC Bus Tour was a complete flop: the day the Bus was supposed to visit Maroubra Beach, a surf carnival was taking place, and the bus could go nowhere near the beach. -

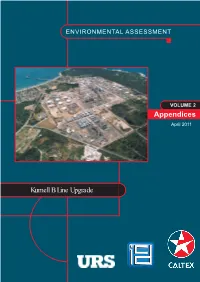

Kurnell B Line Upgrade Appendices

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT VOLUME 2 Appendices April 2011 Kurnell B Line Upgrade Appendix A Director-General’s Requirements A1 Director-General’s Requirements A2 Director-General’s Requirements Response Table Appendix A1 Director-General’s Requirements ----- Forwarded by William Miles/Sydney/URSCorp on 14/02/2011 02:23 p.m. ----- "Wren Suzanne" <[email protected] To <[email protected]> w.gov.au> cc 14/02/2011 02:14 p.m. Subj Caltex Refineries Part 3A Proposal - Council heads of ect consideration for environmental assessment Dear Mr Miles I refer to your letter dated 31 January 2011 regarding the Part 3A Proposal for Caltex Refineries Pty Ltd (Caltex). The proposal includes works to Banksmeadow Terminal which is located in the City of Botany Bay LGA. Council requests that the following heads of consideration be dealt with in the environmental assessment. • Visual impact of the works on the surrounding locality • Pollution that may be generated during the construction period and the operations of the terminal when works are completed • Traffic impacts that may occur on the surrounding road networks due to construction related vehicles accessing the site • Impact on any vegetation • Noise impacts that may be generated during the construction period and the operations of the terminal when works are completed • Contamination and Acid Sulfate Soils on site • Vibration impacts that may occur due to the works Council would also like to review and make a formal submission to the proposal during the exhibition period. Please note, I met you on site and I am Council’s contact officer for this matter. My contact details are below. -

Statement of Management Intent: Malabar Headland National Park

Statement of Management Intent Malabar Headland National Park 1. Introduction This statement outlines the main values, issues, management directions and priorities of the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) for managing Malabar Headland National Park. This statement, together with relevant NPWS policies, will guide the management of the park until a plan of management has been prepared in accordance with the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act). The NPWS Managing Parks Prior to Plan of Management Policy states that parks and reserves without a plan of management are to be managed in a manner consistent with the intent of the NPW Act and the ‘precautionary principle’ (see Principle 15). 2. Management principles National parks are reserved under the NPW Act to protect and conserve areas containing outstanding or representative ecosystems, natural or cultural features or landscapes or phenomena that provide opportunities for public appreciation, inspiration and sustainable visitor or tourist use and enjoyment. Under the NPW Act (section 30E), national parks are managed to: • conserve biodiversity, maintain ecosystem functions, and protect geological and geomorphological features and natural phenomena and maintain natural landscapes • conserve places, objects, features and landscapes of cultural value • protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations • promote public appreciation and understanding of the park’s natural and cultural values • provide for sustainable visitor or tourist use and enjoyment that is compatible with conservation of natural and cultural values • provide for sustainable use (including adaptive reuse) of any buildings or structures or modified natural areas having regard to conservation of natural and cultural values • provide for appropriate research and monitoring.