Giant Waves at Lituya Bay, Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind-Caused Waves Misleads Us Energy Is Transferred to the Wave

WAVES IN WATER is quite similar. Most waves are created by the frictional drag of wind blowing across the water surface. A wave begins as Tsunami can be the most overwhelming of all waves, but a tiny ripple. Once formed, the side of a ripple increases the their origins and behaviors differ from those of the every day waves we see at the seashore or lakeshore. The familiar surface area of water, allowing the wind to push the ripple into waves are caused by wind blowing over the water surface. a higher and higher wave. As a wave gets bigger, more wind Our experience with these wind-caused waves misleads us energy is transferred to the wave. How tall a wave becomes in understanding tsunami. Let us first understand everyday, depends on (1) the velocity of the wind, (2) the duration of wind-caused waves and then contrast them with tsunami. time the wind blows, (3) the length of water surface (fetch) the wind blows across, and (4) the consistency of wind direction. Once waves are formed, their energy pulses can travel thou Wind-Caused Waves sands of kilometers away from the winds that created them. Waves transfer energy away from some disturbance. Waves moving through a water mass cause water particles to rotate in WHY A WIND-BLOWN WAVE BREAKS place, similar to the passage of seismic waves (figure 8.5; see Waves undergo changes when they move into shallow water figure 3.18). You can feel the orbital motion within waves by water with depths less than one-half their wavelength. -

The Exchange of Water Between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska Recommended

The exchange of water between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors Schmidt, George Michael Download date 27/09/2021 18:58:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/5284 THE EXCHANGE OF WATER BETWEEN PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND AND THE GULF OF ALASKA RECOMMENDED: THE EXCHANGE OF WATER BETWEEN PRIMCE WILLIAM SOUND AND THE GULF OF ALASKA A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE by George Michael Schmidt III, B.E.S. Fairbanks, Alaska May 197 7 ABSTRACT Prince William Sound is a complex fjord-type estuarine system bordering the northern Gulf of Alaska. This study is an analysis of exchange between Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska. Warm, high salinity deep water appears outside the Sound during summer and early autumn. Exchange between this ocean water and fjord water is a combination of deep and intermediate advective intrusions plus deep diffusive mixing. Intermediate exchange appears to be an annual phen omenon occurring throughout the summer. During this season, medium scale parcels of ocean water centered on temperature and NO maxima appear in the intermediate depth fjord water. Deep advective exchange also occurs as a regular annual event through the late summer and early autumn. Deep diffusive exchange probably occurs throughout the year, being more evident during the winter in the absence of advective intrusions. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Appreciation is extended to Dr. T. C. Royer, Dr. J. M. Colonell, Dr. R. T. Cooney, Dr. R. -

Coastal Water Levels

Guidance for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping Coastal Water Levels May 2016 Requirements for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Risk Mapping, Assessment, and Planning (Risk MAP) Program are specified separately by statute, regulation, or FEMA policy (primarily the Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping). This document provides guidance to support the requirements and recommends approaches for effective and efficient implementation. Alternate approaches that comply with all requirements are acceptable. For more information, please visit the FEMA Guidelines and Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping webpage (www.fema.gov/guidelines-and-standards-flood-risk-analysis-and- mapping). Copies of the Standards for Flood Risk Analysis and Mapping policy, related guidance, technical references, and other information about the guidelines and standards development process are all available here. You can also search directly by document title at www.fema.gov/library. Water Levels May 2016 Guidance Document 67 Page i Document History Affected Section or Date Description Subsection Initial version of new transformed guidance. The content was derived from the Guidelines and Specifications for Flood Hazard Mapping Partners, Procedure Memoranda, First Publication May 2016 and/or Operating Guidance documents. It has been reorganized and is being published separately from the standards. Water Levels May 2016 Guidance Document 67 Page ii Table of Contents 1.0 Topic Overview ................................................................................................................. -

Tsunami, Seiches, and Tides Key Ideas Seiches

Tsunami, Seiches, And Tides Key Ideas l The wavelengths of tsunami, seiches and tides are so great that they always behave as shallow-water waves. l Because wave speed is proportional to wavelength, these waves move rapidly through the water. l A seiche is a pendulum-like rocking of water in a basin. l Tsunami are caused by displacement of water by forces that cause earthquakes, by landslides, by eruptions or by asteroid impacts. l Tides are caused by the gravitational attraction of the sun and the moon, by inertia, and by basin resonance. 1 Seiches What are the characteristics of a seiche? Water rocking back and forth at a specific resonant frequency in a confined area is a seiche. Seiches are also called standing waves. The node is the position in a standing wave where water moves sideways, but does not rise or fall. 2 1 Seiches A seiche in Lake Geneva. The blue line represents the hypothetical whole wave of which the seiche is a part. 3 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves Tsunami are long-wavelength, shallow-water, progressive waves caused by the rapid displacement of ocean water. Tsunami generated by the vertical movement of earth along faults are seismic sea waves. What else can generate tsunami? llandslides licebergs falling from glaciers lvolcanic eruptions lother direct displacements of the water surface 4 2 Tsunami and Seismic Sea Waves A tsunami, which occurred in 1946, was generated by a rupture along a submerged fault. The tsunami traveled at speeds of 212 meters per second. 5 Tsunami Speed How can the speed of a tsunami be calculated? Remember, because tsunami have extremely long wavelengths, they always behave as shallow water waves. -

Tsunamis in Alaska

Tsunami What is a Tsunami? A tsunami is a series of traveling waves in water that are generated by violent vertical displacement of the water surface. Tsunamis travel up to 500 mph across deep water away from their generation zone. Over the deep ocean, there may be very little displacement of the water surface; but since the wave encompasses the depth of the water column, wave amplitude will increase dramatically as it encounters shallow coastal waters. In many cases, a El Niño tsunami wave appears like an endlessly onrushing tide which forces its way around through any obstacle. The image on the left illustrates how the amplitude of a tsunami wave increases as it moves from the deep ocean water to the shallow coast. Over deep water, the wave length is long, and the wave velocity is very fast. By the time the wave reaches the coast, wave length decreases quickly and wave speed slows dramatically. As this takes place, wave height builds up as it prepares to inundate the shore. Why do Tsunamis occur in Alaska? Subduction-zone mega-thrust earthquakes, the most powerful earthquakes in the world, can produce tsunamis through fault boundary rupture, deformation of an overlying plate, and landslides induced by the earthquake (IRIS, 2016). Megathrust earthquakes occur along subduction zones, such as those found along the ring of fire (see image to the right). The ring of fire extends northward along the coast of western North America, then arcs westward along the southern side of the Aleutians, before curving southwest along the coast of Asia. -

Bathymetry and Geomorphology of Shelikof Strait and the Western Gulf of Alaska

geosciences Article Bathymetry and Geomorphology of Shelikof Strait and the Western Gulf of Alaska Mark Zimmermann 1,* , Megan M. Prescott 2 and Peter J. Haeussler 3 1 National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Seattle, WA 98115, USA 2 Lynker Technologies, Under contract to Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, WA 98115, USA; [email protected] 3 U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99058, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-526-4119 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 19 September 2019; Published: 21 September 2019 Abstract: We defined the bathymetry of Shelikof Strait and the western Gulf of Alaska (WGOA) from the edges of the land masses down to about 7000 m deep in the Aleutian Trench. This map was produced by combining soundings from historical National Ocean Service (NOS) smooth sheets (2.7 million soundings); shallow multibeam and LIDAR (light detection and ranging) data sets from the NOS and others (subsampled to 2.6 million soundings); and deep multibeam (subsampled to 3.3 million soundings), single-beam, and underway files from fisheries research cruises (9.1 million soundings). These legacy smooth sheet data, some over a century old, were the best descriptor of much of the shallower and inshore areas, but they are superseded by the newer multibeam and LIDAR, where available. Much of the offshore area is only mapped by non-hydrographic single-beam and underway files. We combined these disparate data sets by proofing them against their source files, where possible, in an attempt to preserve seafloor features for research purposes. -

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S

2018 NOAA Science Report National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NOAA Research Council-001 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 NATIONAL OCEANIC AND NOAA Research Council noaa ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION 2018 NOAA Science Report Harry Cikanek, Ned Cyr, Ming Ji, Gary Matlock, Steve Thur NOAA Silver Spring, Maryland February 2019 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC National Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF AND ATMOSPHERIC Atmospheric Administration COMMERCE ADMINISTRATION Research Council Wilbur Ross RDML Tim Gallaudet, Ph.D., Craig N. McLean Secretary USN Ret., Acting NOAA NOAA Research Council Chair Administrator Francisco Werner, Ph.D. NOAA Research Council Vice Chair NOTICE This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency or Contractor thereof. Neither the United States Government, nor Contractor, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. -

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program

Technical Report Number 36 Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program Sponsor: Bureau of Land Management Alaska Outer Northern Gulf of Alaska Petroleum Development Scenarios Sociocultural Impacts The United States Department of the Interior was designated by the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act of 1953 to carry out the majority of the Act’s provisions for administering the mineral leasing and develop- ment of offshore areas of the United States under federal jurisdiction. Within the Department, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has the responsibility to meet requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) as well as other legislation and regulations dealing with the effects of offshore development. In Alaska, unique cultural differences and climatic conditions create a need for developing addi- tional socioeconomic and environmental information to improve OCS deci- sion making at all governmental levels. In fulfillment of its federal responsibilities and with an awareness of these additional information needs, the BLM has initiated several investigative programs, one of which is the Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program (SESP). The Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program is a multi-year research effort which attempts to predict and evaluate the effects of Alaska OCS Petroleum Development upon the physical, social, and economic environ- ments within the state. The overall methodology is divided into three broad research components. The first component identifies an alterna- tive set of assumptions regarding the location, the nature, and the timing of future petroleum events and related activities. In this component, the program takes into account the particular needs of the petroleum industry and projects the human, technological, economic, and environmental offshore and onshore development requirements of the regional petroleum industry. -

Numerical Calculation of Seiche Motions in Harbours of Arbitrary Shape

NUMERICAL CALCULATION OF SEICHE MOTIONS IN HARBOURS OF ARBITRARY SHAPE P. Gaillard Sogreah, Grenoble, France ABSTRACT A new method of calculation of wave diffraction around islands, off- shore structures, and of long wave oscillations within offshore or shore-connected harbours is presented. The method is a combination of the finite element technique with an analytical representation of the wave pattern in the far field. Examples of application are given, and results are compared with other theoretical and experimental investig- ations. INTRODUCTION The prediction of possible resonant response of harbours to long wave excitation may be an important factor at the design stage. Hydraulic scale models have the disadvantage of introducing some bias in the results due to wave reflection on the wave paddle and on the tank boundaries. Numerical methods on the other hand can avoid such spurious effects by an appropriate representation of the unbounded water medium outside the harbour. Various numerical methods exist for calculating the seiche motions in harbours of arbitrary shape and water depth configuration. Among these, the hybrid-element methods, as described by Berkhoff [l] , Bettess and Zienkiewicz [2] , Chen and Mei [3j , Sakai and Tsukioka [8] use a com- bination of the finite element technique with other methods for repre- senting the velocity potential within the harbour and in the offshore zone. This paper presents a new method based on the same general approach, with an analytical representation of the wave pattern in the far field. It differs from the former methods in several aspects stressed hereafter. We consider here two kinds of applications: a) the first is the study of wave diffraction by islands or bottom seated obstacles in the open sea and the study of wave oscil- lations within and around an offshore harbour. -

Spanning the Bering Strait

National Park service shared beringian heritage Program U.s. Department of the interior Spanning the Bering Strait 20 years of collaborative research s U b s i s t e N c e h UN t e r i N c h UK o t K a , r U s s i a i N t r o DU c t i o N cean Arctic O N O R T H E L A Chu a e S T kchi Se n R A LASKA a SIBERIA er U C h v u B R i k R S otk S a e i a P v I A en r e m in i n USA r y s M l u l g o a a S K S ew la c ard Peninsu r k t e e r Riv n a n z uko i i Y e t R i v e r ering Sea la B u s n i CANADA n e P la u a ns k ni t Pe a ka N h las c A lf of Alaska m u a G K W E 0 250 500 Pacific Ocean miles S USA The Shared Beringian Heritage Program has been fortunate enough to have had a sustained source of funds to support 3 community based projects and research since its creation in 1991. Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev expanded their cooperation in the field of environmental protection and the study of global change to create the Shared Beringian Heritage Program. -

Flow of Pacific Water in the Western Chukchi

Deep-Sea Research I 105 (2015) 53–73 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Deep-Sea Research I journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri Flow of pacific water in the western Chukchi Sea: Results from the 2009 RUSALCA expedition Maria N. Pisareva a,n, Robert S. Pickart b, M.A. Spall b, C. Nobre b, D.J. Torres b, G.W.K. Moore c, Terry E. Whitledge d a P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, 36, Nakhimovski Prospect, Moscow 117997, Russia b Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 266 Woods Hole Road, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA c Department of Physics, University of Toronto, 60 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 1A7, Canada d University of Alaska Fairbanks, 505 South Chandalar Drive, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA article info abstract Article history: The distribution of water masses and their circulation on the western Chukchi Sea shelf are investigated Received 10 March 2015 using shipboard data from the 2009 Russian-American Long Term Census of the Arctic (RUSALCA) pro- Received in revised form gram. Eleven hydrographic/velocity transects were occupied during September of that year, including a 25 August 2015 number of sections in the vicinity of Wrangel Island and Herald canyon, an area with historically few Accepted 25 August 2015 measurements. We focus on four water masses: Alaskan coastal water (ACW), summer Bering Sea water Available online 31 August 2015 (BSW), Siberian coastal water (SCW), and remnant Pacific winter water (RWW). In some respects the Keywords: spatial distributions of these water masses were similar to the patterns found in the historical World Arctic Ocean Ocean Database, but there were significant differences. -

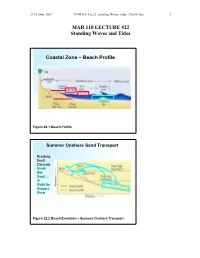

MAR 110 LECTURE #22 Standing Waves and Tides

27 October 2007 MAR110_Lec22_standing Waves_tides_27oct07.doc 1 MAR 110 LECTURE #22 Standing Waves and Tides Coastal Zone – Beach Profile Figure 22.1 Beach Profile Summer Onshore Sand Transport Breaking Swell Currents Erode Bar Sand…. & Build the Summer Berm Figure 22.2 Beach Evolution – Summer Onshore Transport 27 October 2007 MAR110_Lec22_standing Waves_tides_27oct07.doc 2 Winter Offshore Sand Transport Winter Storm Wave Currents Erode Beach Sand…. to form sandbars Figure 22.3 Beach Evolution – Winter Offshore Transport No Net Motion or Energy Propagation Figure 22.4 Wave Reflection and Standing Waves A standing wave does not travel or propagate but merely oscillates up and down with stationary nodes (with no vertical movement) and antinodes (with the maximum possible movement) that oscillates between the crest and the trough. A standing wave occurs when the wave hits a barrier such as a seawall exactly at either the wave’s crest or trough, causing the reflected wave to be a mirror image of the original. (??) 27 October 2007 MAR110_Lec22_standing Waves_tides_27oct07.doc 3 Standing Waves and a Bathtub Seiche Figure 22.5 Standing Waves Standing waves can also occur in an enclosed basin such as a bathtub. In such a case, at the center of the basin there is no vertical movement and the location of this node does not change while at either end is the maximum vertical oscillation of the water. This type of waves is also known as a seiche and occurs in harbors and in large enclosed bodies of water such as the Great Lakes. (??, ??) Standing Wave or Seiche Period l Figure 22.6 Seiche Period The wavelength of a standing wave is equal to twice the length of the basin it is in, which along with the depth (d) of the water within the basin, determines the period (T) of the wave.