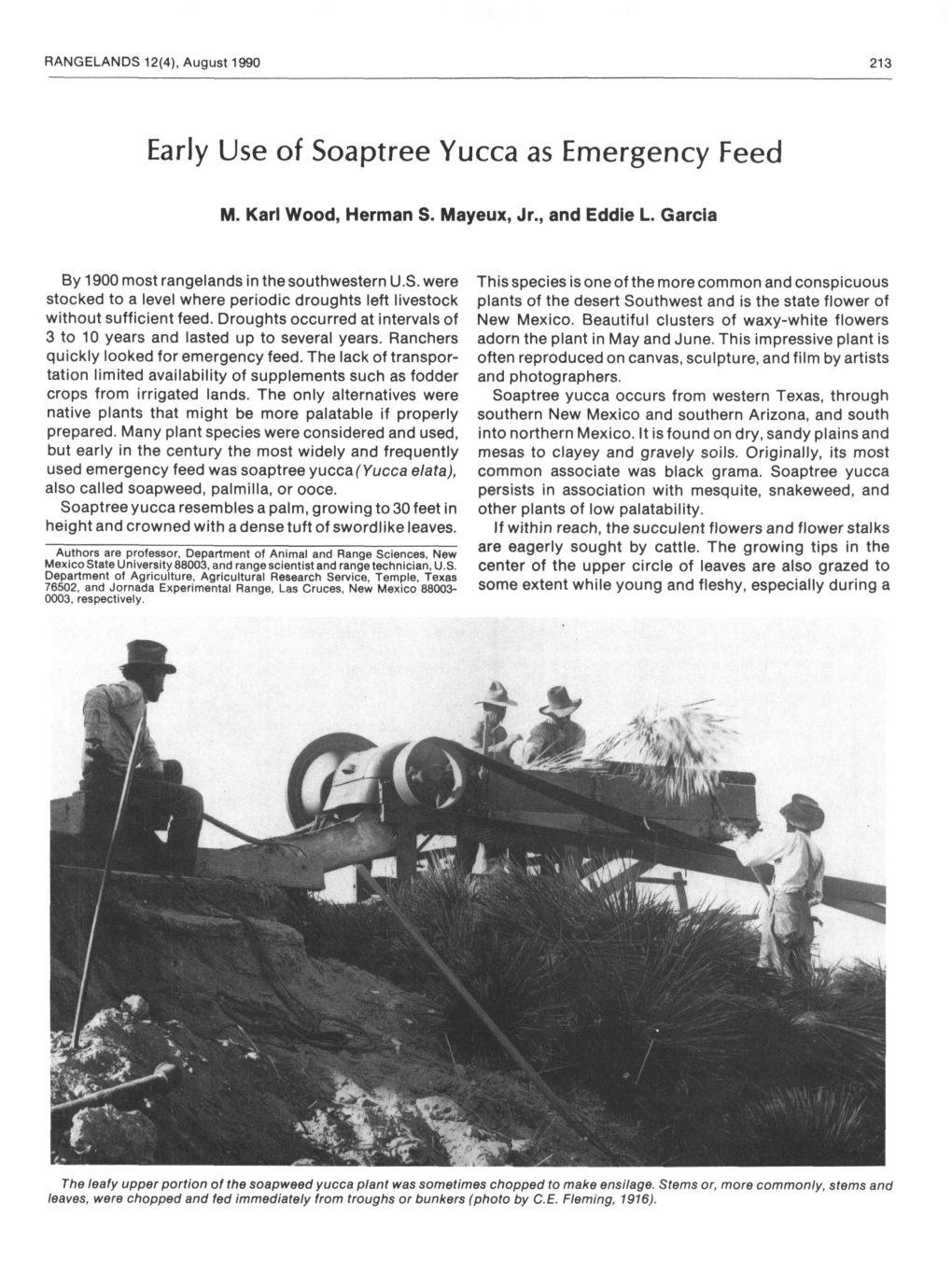

Early Use of Soaptree Yucca As Emergency Feed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico

Cultural Resources Overview Desert Peaks Complex of the Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks National Monument Doña Ana County, New Mexico Myles R. Miller, Lawrence L. Loendorf, Tim Graves, Mark Sechrist, Mark Willis, and Margaret Berrier Report submitted to the Wilderness Society Sacred Sites Research, Inc. July 18, 2017 Public Version This version of the Cultural Resources overview is intended for public distribution. Sensitive information on site locations, including maps and geographic coordinates, has been removed in accordance with State and Federal antiquities regulations. Executive Summary Since the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966, at least 50 cultural resource surveys or reviews have been conducted within the boundaries of the Desert Peaks Complex. These surveys were conducted under Sections 106 and 110 of the NHPA. More recently, local avocational archaeologists and supporters of the Organ Monument-Desert Peaks National Monument have recorded several significant rock art sites along Broad and Valles canyons. A review of site records on file at the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division and consultations with regional archaeologists compiled information on over 160 prehistoric and historic archaeological sites in the Desert Peaks Complex. Hundreds of additional sites have yet to be discovered and recorded throughout the complex. The known sites represent over 13,000 years of prehistory and history, from the first New World hunters who gazed at the nighttime stars to modern astronomers who studied the same stars while peering through telescopes on Magdalena Peak. Prehistoric sites in the complex include ancient hunting and gathering sites, earth oven pits where agave and yucca were baked for food and fermented mescal, pithouse and pueblo villages occupied by early farmers of the Southwest, quarry sites where materials for stone tools were obtained, and caves and shrines used for rituals and ceremonies. -

General Geology of the Franklin Mountains, El Paso County, Texas

THE GENERAL GEOLOGY OF THE FRANKLIN MOUNTAINS, EL PASO COUNTY, TEXAS EL PASO GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY AND PERMIAN BASIN SOCIETY OF ECONOMIC PALEONTOLOGISTS AND MINERALOGISTS FEBRUARY 24, 1968 Society Members Permian Basin Section El Paso Geological Society Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists Robert Habbit, President W.F. Anderson, President David V. LeMone, Vice President Richard C. Todd, First Vice President Karl W. Klement, Second Vice President Charles Crowley, Secretary Kenneth O. Sewald, Secretary William S. Strain Gerald L. Scott, Treasurer Editor and Coordinator: David V. LeMone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ............................................................................. ii Robert Habbit General Geology of the Franklin Mountains: Road Log .......................................... 1 David V. LeMone Precambrian Rocks of the Fusselman Canyon Area ............................................. 12 W.N. McAnulty, Jr. Paleoecology of a Canadian (Lower Ordovician) Algal Complex .................................. 15 David V. LeMone Late Paleozoic in the El Paso Border Region .................................................. 16 Frank E. Kottlowski Late Cenozoic Strata of the El Paso Area ..................................................... 17 William S.Strain A Preliminary Note on the Geology of the Campus “Andesite .................................... 18 Jerry M. Hoffer Conjectural Dating by Means of Gravity Slide Masses of Cenozoic Tectonics of the Southern Franklin Mountains, El Paso County, Texas .......................................... -

Estimating Small Grain Equivalents of Shrub-Dominated Rangelands for Wind Erosion Control

Estimating Small Grain Equivalents of Shrub-Dominated Rangelands for Wind Erosion Control L. J. Hagen, Leon Lyles ASSOC. MEMBER MEMBER ASAE ASAE ABSTRACT management systems. Current procedures for evaluating wind erosion equation, which estimates average wind erosion control practices utilize the wind erosion Aannual erosion, requires that all vegetative cover be equation (Woodruff and Siddoway, 1965). To use the expressed as dry biomass per unit area of flat small grain equation, one must express all vegetative cover in terms equivalent (SG)e. For a standing vegetative canopy, the of its equivalent to a small grain dry above-ground (SG)e depends on the magnitude of the friction velocity biomass reference standard (SO^. Prediction equations reaching an underlying erodible surface. The soil surface have been developed to predict (SG)e for several range friction velocity, and thus (SG)^, was shown to be a grasses (Lyles and Allison, 1980), as well as flat and function of aerodynamic roughness length of the canopy standing crop residues (Lyles and Allison, 1981). and the product of a drag coefficient and plant area However, (SG)^ prediction equations are lacking for index. Aerodynamic roughness, as well as canopy various shrub species to evaluate their ability to control silhouette area and mass distribution, were measured in wind erosion. sand sagebrush {Artemisia filifolia Nutt.) and yucca The standard procedure to evaluate (50)^ of plants is {Yucca elata Englem.) canopies. Estimating equations to conduct laboratory wind tunnel tests on the plants at were developed to predict (SG)^ of the sagebrush and various plant populations. Shrubs present special yucca canopies using either above-ground dry biomass or challenges, however, because many are too large to fit in plant area index as inputs. -

Classification and Phylogenetic Systematics: a Review of Concepts with Examples from the Agave Family

Classification and Phylogenetic Systematics: A review of concepts with examples from the Agave Family David Bogler Missouri Botanical Garden • Taxonomy – the orderly classification of organisms and other objects • Systematics – scientific study of the diversity of organisms – Classification – arrangement into groups – Nomenclature – scientific names – Phylogenetics – evolutionary history • Cladistics – study of relationships of groups of organisms depicted by evolutionary trees, and the methods used to make those trees (parsimony, maximum likelihood, bayesian) “El Sotol” - Dasylirion Dasylirion wheeleri Dasylirion gentryi Agave havardii, Chisos Mountains Agavaceae Distribution Aristotle’s Scala Naturae Great Chain of Being 1579, Didacus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana hierarchical structure of all matter and life, believed to have been decreed by God Middle Ages Ruins of Rome Age of Herbalists Greek Authorities Aristotle Theophrastus Dioscorides Latin was the common language of scholars Plants and animals given Latinized names Stairway to Heaven From Llull (1304). Note that Homo is between the plant-animal steps and the sky-angel- god steps. Systematics - Three Kinds of Classification Systems Artificial - based on similarities that might put unrelated plants in the same category. - Linnaeus. Natural - categories reflect relationships as they really are in nature. - de Jussieu. Phylogenetic - categories based on evolutionary relationships. Current emphasis on monophyletic groups. - Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. Carolus Linnaeus 1707 - 1778 Tried to name and classify all organism Binomial nomenclature Genus species Species Plantarum - 1753 System of Classification “Sexual System” Classes - number of stamens Orders - number of pistils Linnaean Hierarchy Nested box-within-box hierarchy is consistent with descent from a common ancestor, used as evidence by Darwin Nomenclature – system of naming species and higher taxa. -

TAXON:Yucca Gloriosa L. SCORE:11.0 RATING:High Risk

TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L. SCORE: 11.0 RATING: High Risk Taxon: Yucca gloriosa L. Family: Asparagaceae Common Name(s): palmlilja Synonym(s): Yucca acuminata Sweet Spanish dagger Yucca acutifolia Truff. Yucca ellacombei Baker Yucca ensifolia Groenl. Yucca integerrima Stokes Yucca obliqua Haw. Yucca patens André Yucca plicata (Carrière) K.Koch Yucca plicatilis K.Koch Yucca pruinosa Baker Yucca tortulata Baker Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 15 Nov 2017 WRA Score: 11.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Naturalized, Weedy Succulent, Spine-tipped Leaves, Moth-pollinated Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) Intermediate tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 15 Nov 2017 (Yucca gloriosa L.) Page 1 of 21 TAXON: Yucca gloriosa L. -

Yucca: a Medicinally Significant Genus with Manifold Therapeutic Attributes

Review Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2012, 2, 231–234 DOI 10.1007/s13659-012-0090-4 Yucca: A medicinally significant genus with manifold therapeutic attributes Seema PATEL* Better Process Control School, Department of Food Science and Technology, University of California Davis, California, United States Received 9 November 2012; Accepted 20 November 2012 © The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract: The genus Yucca comprising of several species is dominant across the chaparrals, canyons and deserts of American South West and Mexico. This genus has long been a source of sustenance and drugs for the Native Americans. In the wake of revived interest in drug discovery from plant sources, this genus has been investigated and startling nutritive and therapeutic capacities have come forth. Apart from the functional food potential, antioxidant, antiinflammation, antiarthritic, anticancer, antidiabetic, antimicrobial, and hypocholesterolaemic properties have also been revealed. Steroidal saponins, resveratrol and yuccaols have been identified to be the active principles with myriad biological actions. To stimulate further research on this genus of multiple food and pharmaceutical uses, this updated review has been prepared with references extracted from MEDLINE database. Keywords: Yucca, saponin, antioxidant, cytotoxicity, antimicrobial Introduction filamentosa as medicines and soap. The roots were crushed to The genus Yucca belongs to Asparagaceae family and make poultice for wound healing. Further, the roots were used encompasses about 40–50 medicinally potent plants. These to cure gonorrhoea and rheumatism. The Zuni tribe inhabiting flowering plants generally thrive in arid parts of Southwestern the western New Mexico region used Yucca elata sap as hair US and Mexico, namely Mojave, Sonoran, Colorado and growth stimulant. -

Phoenix AMA LWUPL

Arizona Department of Water Resources Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Official Regulatory List for the Phoenix Active Management Area Fourth Management Plan Arizona Department of Water Resources 1110 West Washington St. Ste. 310 Phoenix, AZ 85007 www.azwater.gov 602-771-8585 Phoenix Active Management Area Low-Water-Use/Drought-Tolerant Plant List Acknowledgements The Phoenix AMA list was prepared in 2004 by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) in cooperation with the Landscape Technical Advisory Committee of the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association, comprised of experts from the Desert Botanical Garden, the Arizona Department of Transporation and various municipal, nursery and landscape specialists. ADWR extends its gratitude to the following members of the Plant List Advisory Committee for their generous contribution of time and expertise: Rita Jo Anthony, Wild Seed Judy Mielke, Logan Simpson Design John Augustine, Desert Tree Farm Terry Mikel, U of A Cooperative Extension Robyn Baker, City of Scottsdale Jo Miller, City of Glendale Louisa Ballard, ASU Arboritum Ron Moody, Dixileta Gardens Mike Barry, City of Chandler Ed Mulrean, Arid Zone Trees Richard Bond, City of Tempe Kent Newland, City of Phoenix Donna Difrancesco, City of Mesa Steve Priebe, City of Phornix Joe Ewan, Arizona State University Janet Rademacher, Mountain States Nursery Judy Gausman, AZ Landscape Contractors Assn. Rick Templeton, City of Phoenix Glenn Fahringer, Earth Care Cathy Rymer, Town of Gilbert Cheryl Goar, Arizona Nurssery Assn. Jeff Sargent, City of Peoria Mary Irish, Garden writer Mark Schalliol, ADOT Matt Johnson, U of A Desert Legum Christy Ten Eyck, Ten Eyck Landscape Architects Jeff Lee, City of Mesa Gordon Wahl, ADWR Kirti Mathura, Desert Botanical Garden Karen Young, Town of Gilbert Cover Photo: Blooming Teddy bear cholla (Cylindropuntia bigelovii) at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monutment. -

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Phase II Report

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plant Flora of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Phase II Report By Dr. Terri Hildebrand Southern Utah University, Cedar City, UT and Dr. Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting, Kanab, UT Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Agreement # H1200-09-0005 1 May 2012 Prepared for Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Southern Utah University National Park Service Mojave Network TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # Introduction . 4 Study Area . 6 History and Setting . 6 Geology and Associated Ecoregions . 6 Soils and Climate . 7 Vegetation . 10 Previous Botanical Studies . 11 Methods . 17 Results . 21 Discussion . 28 Conclusions . 32 Acknowledgments . 33 Literature Cited . 34 Figures Figure 1. Location of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in northern Arizona . 5 Figure 2. Ecoregions and 2010-2011 collection sites in Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in northern Arizona . 8 Figure 3. Soil types and 2010-2011 collection sites in Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in northern Arizona . 9 Figure 4. Increase in the number of plant taxa confirmed as present in Grand Canyon- Parashant National Monument by decade, 1900-2011 . 13 Figure 5. Southern Utah University students enrolled in the 2010 Plant Anatomy and Diversity course that collected during the 30 August 2010 experiential learning event . 18 Figure 6. 2010-2011 collection sites and transportation routes in Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in northern Arizona . 22 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # Tables Table 1. Chronology of plant-collecting efforts at Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument . 14 Table 2. Data fields in the annotated checklist of the flora of Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Appendices A, B, C, and D) . -

EA-0847; Environmental Assessment and (FONSI) U

EA-0847; Environmental Assessment and (FONSI) U. S. Department of Energy Central Training Academy Live Fire Range TABLE OF CONTENTS State of New Mexico Approval Department of Energy memorandum SUBJECT: Environmental Assessment (EA) for the Central Training Academy Live Fire Range in Albuquerque, New Mexico DATE July 29, 1993 Environmental Assessment U.S. Department of Energy Central Training Academy Live Fire Range U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT LIVE FIRE RANGE AT THE CENTRAL TRAINING ACADEMY ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO 1.0 BACKGROUND/HISTORY 2.0 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR THE PROPOSED ACTION 3.0 PROPOSED ACTION 4.0 ALTER NATIVE ACTIONS 5.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 5.1 Demography 5.2 Topography 5.3 Land Use 5.4 Geology and Seismology 5.5 Soil 5.6 Hydrology 5.7 Wildlife 5.8 Vegetation 5.9 Cultural Resources 5.10 Waste Management 6.0 ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES 6.1 Potential Impacts from Routine Operations 6.2 Potential Impacts to Vegetation and Soils 6.3 Potential Impacts to Wildlife 6.4 Potential Impact to Threatened. Endangered. or Sensitive Plant Species 6.5 Potential Impacts to Waste Management 6.6 Abnormal Events - Probability and Consequences 6.7 Cumulative Effects 6.8 Impacts from the No Action Alternative 7.0 LISTING OF AGENCIES AND PERSONS CONSULTED 8.0 LIST OF REFERENCES 9.0 LIST OF MAPS 10.0 LIST OF ATTACHMENTS ATTACHMENT 1 Threatened & Endangered Plant Survey Attachment 1. List of plants observed at the Coyote Canyon Firing Range extension site. 4-18-90. Attachment 2. NM Endangered Species Laws Attachment 3. -

Evaluation of Selected Natural Resources in Parts of Loving,Pecos

Area Study: Parts of the Trans-Pecos, Texas Evaluation of Selected Natural Resources in Parts of Loving, Pecos, Reeves, Ward, and Winkler Counties, Texas Pecos River near Girvin, Texas RESOURCE PROTECTION DIVISION: WATER RESOURCES TEAM EVALUATION OF SELECTED NATURAL RESOURCES IN PARTS OF LOVING, PECOS, REEVES, WARD, AND WINKLER COUNTIES, TEXAS By: Albert El-Hage Daniel W. Moulton October 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Tables .........................................................................................................................ii Figures ........................................................................................................................ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.......................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................2 Purpose ......................................................................................................................2 Location and Extent....................................................................................................2 Geography and Ecology..............................................................................................2 Demographics ............................................................................................................5 Economy and Land Use..............................................................................................5 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................6 -

Agricultural Science Center at Farmington March 2018

New Mexico State University 2017 Annual Progress Report Agricultural Science Center at Farmington March 2018 ‘2017 third shortest growing season of 130 days since 1969.’ Snowfall 18 May 2017. Agricultural Science Center - Farmington NMSU Agricultural Science Center - Farmington 2017 Annual Report Fifty-first Annual Progress Report for 2017 New Mexico State University Agricultural Science Center – Farmington P. O. Box 1018 Farmington, NM 87499 - 1018 Permanent Faculty and Staff Kevin Lombard Sue Stone Superintendent, Associate Professor Associate Administrative Assistant Michael K. O'Neill Joseph Ward Professor Research Technician Koffi Djaman Jonah Joe Assistant Professor Research Technician Samuel Allen Franklin Jason Thomas Agricultural Research Scientist Laboratory Research Technician Margaret M. West Dallen Begay Agricultural Research Scientist Farm/Ranch Manager Desiree Deschenie Nathan Begay Agricultural Research Assistant Laborer, Sr. Temporary Employees 2017 Student Employees Brandon Francis Eugena Armijillo Groundskeeper Sr. Ag. Research Assistant Tiffany Charley Research Lab Technician Updated Edition March 2018 Editor - Margaret M. West, Agricultural Research Scientist Cover: The cover photograph depicts a Soaptree yucca, Yucca elata at ASC Farmington’s front entrance taken during the May 18, 2017 snowfall. Learn more about this xeric plant and more at http://farmingtonsc.nmsu.edu/very-low-irrigation.html (Photo credit: M.M. West). i NMSU Agricultural Science Center - Farmington 2017 Annual Report 2017 ASC Advisory Committee -

Tucson AMA Low Water Use/Drought Tolerant Plant List

Arizona Department of Water Resources Tucson Active Management Area Official Regulatory List for the Tucson Active Management Area Fourth Management Plan Arizona Department of Water Resources 1110 W. Washington St, Suite 310 Phoenix, AZ 85007 www.azwater.gov 602-771-8585 Tucson Active Management Area Low Water Use/Drought Tolerant Plant List Low Water Use/Drought Tolerant Plant List Official Regulatory List for the Tucson Active Management Area Arizona Department of Water Resources Acknowledgements The list of plants in this document was prepared in 2010 by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) in cooperation with plant and landscape plant specialists from the Tucson AMA and other experts. ADWR extends its gratitude to the following members of the Tucson AMA Plant List Advisory Committee for their generous contribution of time and expertise: ~Globe Mallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua) cover photo courtesy of Bureau of Land Management, Nevada~ Bruce Munda Tucson Plant Materials , USDA Karen Cesare Novak Environmental Daniel Signor Pima County Larry Woods Rillito Nursery and Garden Center Doug Larson Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Les Shipley Civano Nursery Eric Scharf Wheat Scharf Landscape Architects Lori Woods RECON Environmental, Inc. Gary Wittwer City of Tucson Margaret Livingston University of Arizona Greg Corman Gardening Insights Margaret West MWest Designs Greg Starr Starr Nursery Mark Novak University of Arizona Irene Ogata City of Tucson Paul Bessey University of Arizona, emeritus Jack Kelly University of Arizona Russ Buhrow Tohono Chul Park Jerry O'Neill Tohono Chul Park Scott Calhoun Zona Gardens Joseph Linville City of Tucson A Resource for Regulated Water Users The use of low water use/drought tolerant plants is required in public rights of way and in other instances as described in the Fourth Management Plan1 .