Full-Genome Sequences of Alphacoronaviruses and Astroviruses from Myotis and Pipistrelle Bats in Denmark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

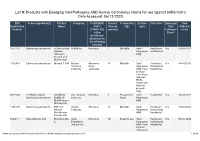

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens and Human Coronavirus Claims for Use Against SARS-Cov-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens AND Human Coronavirus claims for use against SARS-CoV-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact Formulation Surface Use Sites Emerging Date Registration Name CoV-2 Time (in Type Types Viral Added to Number (COVID-19), minutes) Pathogen List N follow Claim? disinfection directions for the following virus(es) 1677-202 Quaternary ammonium 66 Heavy Duty Ecolab Inc Norovirus 2 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Alkaline Nonporous Institutional Bathroom (HN) Cleaner and Disinfectant 10324-81 Quaternary ammonium Maquat 7.5-M Mason Norovirus; 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Chemical Feline Nonporous Institutional; Company calicivirus (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse Required (FCR); Porous (P) (laundry presoak only) 4822-548 Triethylene glycol; Scrubbing S.C. Johnson Rotavirus 5 Pressurized Hard Residential Yes 06/04/2020 Quaternary ammonium Bubbles® & Son Inc liquid Nonporous Multi-Purpose (HN) Disinfectant 1839-167 Quaternary ammonium BTC 885 Stepan Rotavirus 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 Neutral Company Nonporous Institutional; Disinfectant (HN) Residential Cleaner-256 93908-1 Hypochlorous acid Envirolyte O & Aqua Norovirus 10 Ready-to-use Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 G Engineered Nonporous Institutional; Solution Inc (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2 1 of 66 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact -

Identification of Capsid/Coat Related Protein Folds and Their Utility for Virus Classification

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 10 March 2017 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00380 Identification of Capsid/Coat Related Protein Folds and Their Utility for Virus Classification Arshan Nasir 1, 2 and Gustavo Caetano-Anollés 1* 1 Department of Crop Sciences, Evolutionary Bioinformatics Laboratory, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA, 2 Department of Biosciences, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan The viral supergroup includes the entire collection of known and unknown viruses that roam our planet and infect life forms. The supergroup is remarkably diverse both in its genetics and morphology and has historically remained difficult to study and classify. The accumulation of protein structure data in the past few years now provides an excellent opportunity to re-examine the classification and evolution of viruses. Here we scan completely sequenced viral proteomes from all genome types and identify protein folds involved in the formation of viral capsids and virion architectures. Viruses encoding similar capsid/coat related folds were pooled into lineages, after benchmarking against published literature. Remarkably, the in silico exercise reproduced all previously described members of known structure-based viral lineages, along with several proposals for new Edited by: additions, suggesting it could be a useful supplement to experimental approaches and Ricardo Flores, to aid qualitative assessment of viral diversity in metagenome samples. Polytechnic University of Valencia, Spain Keywords: capsid, virion, protein structure, virus taxonomy, SCOP, fold superfamily Reviewed by: Mario A. Fares, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones INTRODUCTION Científicas(CSIC), Spain Janne J. Ravantti, The last few years have dramatically increased our knowledge about viral systematics and University of Helsinki, Finland evolution. -

Virus Particle Structures

Virus Particle Structures Virus Particle Structures Palmenberg, A.C. and Sgro, J.-Y. COLOR PLATE LEGENDS These color plates depict the relative sizes and comparative virion structures of multiple types of viruses. The renderings are based on data from published atomic coordinates as determined by X-ray crystallography. The international online repository for 3D coordinates is the Protein Databank (www.rcsb.org/pdb/), maintained by the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB). The VIPER web site (mmtsb.scripps.edu/viper), maintains a parallel collection of PDB coordinates for icosahedral viruses and additionally offers a version of each data file permuted into the same relative 3D orientation (Reddy, V., Natarajan, P., Okerberg, B., Li, K., Damodaran, K., Morton, R., Brooks, C. and Johnson, J. (2001). J. Virol., 75, 11943-11947). VIPER also contains an excellent repository of instructional materials pertaining to icosahedral symmetry and viral structures. All images presented here, except for the filamentous viruses, used the standard VIPER orientation along the icosahedral 2-fold axis. With the exception of Plate 3 as described below, these images were generated from their atomic coordinates using a novel radial depth-cue colorization technique and the program Rasmol (Sayle, R.A., Milner-White, E.J. (1995). RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci., 20, 374-376). First, the Temperature Factor column for every atom in a PDB coordinate file was edited to record a measure of the radial distance from the virion center. The files were rendered using the Rasmol spacefill menu, with specular and shadow options according to the Van de Waals radius of each atom. -

Prospects of Replication-Deficient Adenovirus Based Vaccine Development Against SARS-Cov-2

Brief Report Prospects of Replication-Deficient Adenovirus Based Vaccine Development against SARS-CoV-2 Mariangela Garofalo 1,* , Monika Staniszewska 2 , Stefano Salmaso 1 , Paolo Caliceti 1, Katarzyna Wanda Pancer 3, Magdalena Wieczorek 3 and Lukasz Kuryk 3,4,* 1 Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, University of Padova, Via F. Marzolo 5, 35131 Padova, Italy; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (P.C.) 2 Chair of Drug and Cosmetics Biotechnology, Faculty of Chemistry, Warsaw University of Technology, Noakowskiego 3, 00-664 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Virology, National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene, Chocimska 24, 00-791 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.W.P.); [email protected] (M.W.) 4 Clinical Science, Targovax Oy, Saukonpaadenranta 2, 00180 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (L.K.) Received: 1 May 2020; Accepted: 6 June 2020; Published: 10 June 2020 Abstract: The current appearance of the new SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and it quickly spreading across the world poses a global health emergency. The serious outbreak position is affecting people worldwide and requires rapid measures to be taken by healthcare systems and governments. Vaccinations represent the most effective strategy to prevent the epidemic of the virus and to further reduce morbidity and mortality with long-lasting effects. Nevertheless, currently there are no licensed vaccines for the novel coronaviruses. Researchers and clinicians from all over the world are advancing the development of a vaccine against novel human SARS-CoV-2 using various approaches. -

Genome Organization of Canada Goose Coronavirus, a Novel

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genome Organization of Canada Goose Coronavirus, A Novel Species Identifed in a Mass Die-of of Received: 14 January 2019 Accepted: 25 March 2019 Canada Geese Published: xx xx xxxx Amber Papineau1,2, Yohannes Berhane1, Todd N. Wylie3,4, Kristine M. Wylie3,4, Samuel Sharpe5 & Oliver Lung 1,2 The complete genome of a novel coronavirus was sequenced directly from the cloacal swab of a Canada goose that perished in a die-of of Canada and Snow geese in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, Canada. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis indicate it is a new species of Gammacoronavirus, as it falls below the threshold of 90% amino acid similarity in the protein domains used to demarcate Coronaviridae. Additional features that distinguish the genome of Canada goose coronavirus include 6 novel ORFs, a partial duplication of the 4 gene and a presumptive change in the proteolytic processing of polyproteins 1a and 1ab. Viruses belonging to the Coronaviridae family have a single stranded positive sense RNA genome of 26–31 kb. Members of this family include both human pathogens, such as severe acute respiratory syn- drome virus (SARS-CoV)1, and animal pathogens, such as porcine epidemic diarrhea virus2. Currently, the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) recognizes four genera in the Coronaviridae family: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. While the reser- voirs of the Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus genera are believed to be bats, the Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus genera have been shown to spread primarily through birds3. Te frst three species of the Deltacoronavirus genus were discovered in 20094 and recent work has vastly expanded the Deltacoronavirus genus, adding seven additional species3. -

Detection and Characterization of a Novel Marine Birnavirus Isolated from Asian Seabass in Singapore

Chen et al. Virology Journal (2019) 16:71 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1174-0 RESEARCH Open Access Detection and characterization of a novel marine birnavirus isolated from Asian seabass in Singapore Jing Chen1†, Xinyu Toh1†, Jasmine Ong1, Yahui Wang1, Xuan-Hui Teo1, Bernett Lee2, Pui-San Wong3, Denyse Khor1, Shin-Min Chong1, Diana Chee1, Alvin Wee1, Yifan Wang1, Mee-Keun Ng1, Boon-Huan Tan3 and Taoqi Huangfu1* Abstract Background: Lates calcarifer, known as seabass in Asia and barramundi in Australia, is a widely farmed species internationally and in Southeast Asia and any disease outbreak will have a great economic impact on the aquaculture industry. Through disease investigation of Asian seabass from a coastal fish farm in 2015 in Singapore, a novel birnavirus named Lates calcarifer Birnavirus (LCBV) was detected and we sought to isolate and characterize the virus through molecular and biochemical methods. Methods: In order to propagate the novel birnavirus LCBV, the virus was inoculated into the Bluegill Fry (BF-2) cell line and similar clinical signs of disease were reproduced in an experimental fish challenge study using the virus isolate. Virus morphology was visualized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Biochemical analysis using chloroform and 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BUDR) sensitivity assays were employed to characterize the virus. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) was also used to obtain the virus genome for genetic and phylogenetic analyses. Results: The LCBV-infected BF-2 cell line showed cytopathic effects such as rounding and granulation of cells, localized cell death and detachment of cells observed at 3 to 5 days’ post-infection. -

Rapid Identification of Known and New RNA Viruses from Animal Tissues

Rapid Identification of Known and New RNA Viruses from Animal Tissues Joseph G. Victoria1,2*, Amit Kapoor1,2, Kent Dupuis3, David P. Schnurr3, Eric L. Delwart1,2 1 Department of Molecular Virology, Blood Systems Research Institute, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 3 Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory, Division of Communicable Disease Control, California State Department of Public Health, Richmond, California, United States of America Abstract Viral surveillance programs or diagnostic labs occasionally obtain infectious samples that fail to be typed by available cell culture, serological, or nucleic acid tests. Five such samples, originating from insect pools, skunk brain, human feces and sewer effluent, collected between 1955 and 1980, resulted in pathology when inoculated into suckling mice. In this study, sequence-independent amplification of partially purified viral nucleic acids and small scale shotgun sequencing was used on mouse brain and muscle tissues. A single viral agent was identified in each sample. For each virus, between 16% to 57% of the viral genome was acquired by sequencing only 42–108 plasmid inserts. Viruses derived from human feces or sewer effluent belonged to the Picornaviridae family and showed between 80% to 91% amino acid identities to known picornaviruses. The complete polyprotein sequence of one virus showed strong similarity to a simian picornavirus sequence in the provisional Sapelovirus genus. Insects and skunk derived viral sequences exhibited amino acid identities ranging from 25% to 98% to the segmented genomes of viruses within the Reoviridae family. Two isolates were highly divergent: one is potentially a new species within the orthoreovirus genus, and the other is a new species within the orbivirus genus. -

Data Mining Cdnas Reveals Three New Single Stranded RNA Viruses in Nasonia (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae)

Insect Molecular Biology Insect Molecular Biology (2010), 19 (Suppl. 1), 99–107 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00934.x Data mining cDNAs reveals three new single stranded RNA viruses in Nasonia (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) D. C. S. G. Oliveira*, W. B. Hunter†, J. Ng*, Small viruses with a positive-sense single-stranded C. A. Desjardins*, P. M. Dang‡ and J. H. Werren* RNA (ssRNA) genome, and no DNA stage, are known as *Department of Biology, University of Rochester, picornaviruses (infecting vertebrates) or picorna-like Rochester, NY, USA; †United States Department of viruses (infecting non-vertebrates). Recently, the order Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, US Picornavirales was formally characterized to include most, Horticultural Research Laboratory, Fort Pierce, FL, USA; but not all, ssRNA viruses (Le Gall et al., 2008). Among and ‡United States Department of Agriculture, other typical characteristics – e.g. a small icosahedral Agricultural Research Service, NPRU, Dawson, GA, capsid with a pseudo-T = 3 symmetry and a 7–12 kb USA genome made of one or two RNA segments – the Picor- navirales genome encodes a polyprotein with a replication Abstractimb_934 99..108 module that includes a helicase, a protease, and an RNA- dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), in this order (see Le We report three novel small RNA viruses uncovered Gall et al., 2008 for details). Pathogenicity of the infections from cDNA libraries from parasitoid wasps in the can vary broadly from devastating epidemics to appar- genus Nasonia. The genome of this kind of virus ently persistent commensal infections. Several human Ј is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA with a 3 diseases, from hepatitis A to the common cold (e.g. -

Downloaded from the Genbank Database As of July 2020

viruses Article Modular Evolution of Coronavirus Genomes Yulia Vakulenko 1,2 , Andrei Deviatkin 3 , Jan Felix Drexler 1,4,5 and Alexander Lukashev 1,3,* 1 Martsinovsky Institute of Medical Parasitology, Tropical and Vector Borne Diseases, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119435 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (Y.V.); [email protected] (J.F.D.) 2 Department of Virology, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119234 Moscow, Russia 3 Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Institute of Molecular Medicine, Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119435 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 4 Institute of Virology, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 10117 Berlin, Germany 5 German Centre for Infection Research (DZIF), Associated Partner Site Charité, 10117 Berlin, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The viral family Coronaviridae comprises four genera, termed Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Deltacoronavirus. Recombination events have been described in many coronaviruses infecting humans and other animals. However, formal analysis of the recombination patterns, both in terms of the involved genome regions and the extent of genetic divergence between partners, are scarce. Common methods of recombination detection based on phylogenetic incongruences (e.g., a phylogenetic com- patibility matrix) may fail in cases where too many events diminish the phylogenetic signal. Thus, an approach comparing genetic distances in distinct genome regions (pairwise distance deviation matrix) was set up. In alpha, beta, and delta-coronaviruses, a low incidence of recombination between closely related viruses was evident in all genome regions, but it was more extensive between the spike gene and other genome regions. -

Canine Coronaviruses: Emerging and Re-Emerging Pathogens of Dogs

1 Berliner und Münchener Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 2021 (134) Institute of Animal Hygiene and Veterinary Public Health, University Leipzig, Open Access Leipzig, Germany Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr (134) 1–6 (2021) Canine coronaviruses: emerging and DOI 10.2376/1439-0299-2021-1 re-emerging pathogens of dogs © 2021 Schlütersche Fachmedien GmbH Ein Unternehmen der Schlüterschen Canine Coronaviren: Neu und erneut auftretende Pathogene Mediengruppe des Hundes ISSN 1439-0299 Korrespondenzadresse: Ahmed Abd El Wahed, Uwe Truyen [email protected] Eingegangen: 08.01.2021 Angenommen: 01.04.2021 Veröffentlicht: 29.04.2021 https://www.vetline.de/berliner-und- muenchener-tieraerztliche-wochenschrift- open-access Summary Canine coronavirus (CCoV) and canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV) are highly infectious viruses of dogs classified as Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus, respectively. Both are examples for viruses causing emerging diseases since CCoV originated from a Feline coronavirus-like Alphacoronavirus and CRCoV from a Bovine coronavirus-like Betacoronavirus. In this review article, differences in the genetic organization of CCoV and CRCoV as well as their relation to other coronaviruses are discussed. Clinical pictures varying from an asymptomatic or mild unspecific disease, to respiratory or even an acute generalized illness are reported. The possible role of dogs in the spread of the Betacoronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is crucial to study as ani- mal always played the role of establishing zoonotic diseases in the community. Keywords: canine coronavirus, canine respiratory coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, genetics, infectious diseases Zusammenfassung Das canine Coronavirus (CCoV) und das canine respiratorische Coronavirus (CRCoV) sind hochinfektiöse Viren von Hunden, die als Alphacoronavirus bzw. -

Emerging Viral Diseases of Fish and Shrimp Peter J

Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp Peter J. Walker, James R. Winton To cite this version: Peter J. Walker, James R. Winton. Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp. Veterinary Research, BioMed Central, 2010, 41 (6), 10.1051/vetres/2010022. hal-00903183 HAL Id: hal-00903183 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00903183 Submitted on 1 Jan 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vet. Res. (2010) 41:51 www.vetres.org DOI: 10.1051/vetres/2010022 Ó INRA, EDP Sciences, 2010 Review article Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp 1 2 Peter J. WALKER *, James R. WINTON 1 CSIRO Livestock Industries, Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL), 5 Portarlington Road, Geelong, Victoria, Australia 2 USGS Western Fisheries Research Center, 6505 NE 65th Street, Seattle, Washington, USA (Received 7 December 2009; accepted 19 April 2010) Abstract – The rise of aquaculture has been one of the most profound changes in global food production of the past 100 years. Driven by population growth, rising demand for seafood and a levelling of production from capture fisheries, the practice of farming aquatic animals has expanded rapidly to become a major global industry. -

Aquatic Animal Viruses Mediated Immune Evasion in Their Host T ∗ Fei Ke, Qi-Ya Zhang

Fish and Shellfish Immunology 86 (2019) 1096–1105 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fish and Shellfish Immunology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fsi Aquatic animal viruses mediated immune evasion in their host T ∗ Fei Ke, Qi-Ya Zhang State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan, 430072, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Viruses are important and lethal pathogens that hamper aquatic animals. The result of the battle between host Aquatic animal virus and virus would determine the occurrence of diseases. The host will fight against virus infection with various Immune evasion responses such as innate immunity, adaptive immunity, apoptosis, and so on. On the other hand, the virus also Virus-host interactions develops numerous strategies such as immune evasion to antagonize host antiviral responses. Here, We review Virus targeted molecular and pathway the research advances on virus mediated immune evasions to host responses containing interferon response, NF- Host responses κB signaling, apoptosis, and adaptive response, which are executed by viral genes, proteins, and miRNAs from different aquatic animal viruses including Alloherpesviridae, Iridoviridae, Nimaviridae, Birnaviridae, Reoviridae, and Rhabdoviridae. Thus, it will facilitate the understanding of aquatic animal virus mediated immune evasion and potentially benefit the development of novel antiviral applications. 1. Introduction Various antiviral responses have been revealed [19–22]. How they are overcome by different viruses? Here, we select twenty three strains Aquatic viruses have been an essential part of the biosphere, and of aquatic animal viruses which represent great harms to aquatic ani- also a part of human and aquatic animal lives.