Prospects of Replication-Deficient Adenovirus Based Vaccine Development Against SARS-Cov-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

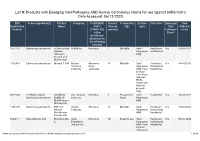

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens and Human Coronavirus Claims for Use Against SARS-Cov-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020

List N: Products with Emerging Viral Pathogens AND Human Coronavirus claims for use against SARS-CoV-2 Date Accessed: 06/12/2020 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact Formulation Surface Use Sites Emerging Date Registration Name CoV-2 Time (in Type Types Viral Added to Number (COVID-19), minutes) Pathogen List N follow Claim? disinfection directions for the following virus(es) 1677-202 Quaternary ammonium 66 Heavy Duty Ecolab Inc Norovirus 2 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Alkaline Nonporous Institutional Bathroom (HN) Cleaner and Disinfectant 10324-81 Quaternary ammonium Maquat 7.5-M Mason Norovirus; 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 06/04/2020 Chemical Feline Nonporous Institutional; Company calicivirus (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse Required (FCR); Porous (P) (laundry presoak only) 4822-548 Triethylene glycol; Scrubbing S.C. Johnson Rotavirus 5 Pressurized Hard Residential Yes 06/04/2020 Quaternary ammonium Bubbles® & Son Inc liquid Nonporous Multi-Purpose (HN) Disinfectant 1839-167 Quaternary ammonium BTC 885 Stepan Rotavirus 10 Dilutable Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 Neutral Company Nonporous Institutional; Disinfectant (HN) Residential Cleaner-256 93908-1 Hypochlorous acid Envirolyte O & Aqua Norovirus 10 Ready-to-use Hard Healthcare; Yes 05/28/2020 G Engineered Nonporous Institutional; Solution Inc (HN); Food Residential Contact Post-Rinse www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2 1 of 66 EPA Active Ingredient(s) Product Company To kill SARS- Contact -

A Human Coronavirus Evolves Antigenically to Escape Antibody Immunity

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.17.423313; this version posted December 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A human coronavirus evolves antigenically to escape antibody immunity Rachel Eguia1, Katharine H. D. Crawford1,2,3, Terry Stevens-Ayers4, Laurel Kelnhofer-Millevolte3, Alexander L. Greninger4,5, Janet A. Englund6,7, Michael J. Boeckh4, Jesse D. Bloom1,2,# 1Basic Sciences and Computational Biology, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA 2Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 3Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 4Vaccine and Infectious Diseases Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA 5Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 6Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA USA 7Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA USA 8Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Seattle, WA 98109 #Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract There is intense interest in antibody immunity to coronaviruses. However, it is unknown if coronaviruses evolve to escape such immunity, and if so, how rapidly. Here we address this question by characterizing the historical evolution of human coronavirus 229E. We identify human sera from the 1980s and 1990s that have neutralizing titers against contemporaneous 229E that are comparable to the anti-SARS-CoV-2 titers induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination. -

Common Human Coronaviruses

Common Human Coronaviruses Common human coronaviruses, including types 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold. Most people get infected with one or more of these viruses at some point in their lives. This information applies to common human coronaviruses and should not be confused with Coronavirus Disease-2019 (formerly referred to as 2019 Novel Coronavirus). Symptoms of common human coronaviruses Treatment for common human coronaviruses • runny nose • sore throat There is no vaccine to protect you against human • headache • fever coronaviruses and there are no specific treatments for illnesses caused by human coronaviruses. Most people with • cough • general feeling of being unwell common human coronavirus illness will recover on their Human coronaviruses can sometimes cause lower- own. However, to relieve your symptoms you can: respiratory tract illnesses, such as pneumonia or bronchitis. • take pain and fever medications (Caution: do not give This is more common in people with cardiopulmonary aspirin to children) disease, people with weakened immune systems, infants, and older adults. • use a room humidifier or take a hot shower to help ease a sore throat and cough Transmission of common human coronaviruses • drink plenty of liquids Common human coronaviruses usually spread from an • stay home and rest infected person to others through If you are concerned about your symptoms, contact your • the air by coughing and sneezing healthcare provider. • close personal contact, like touching or shaking hands Testing for common human coronaviruses • touching an object or surface with the virus on it, then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes before washing Sometimes, respiratory secretions are tested to figure out your hands which specific germ is causing your symptoms. -

Early Surveillance and Public Health Emergency Responses Between Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Avian Influenza in China: a Case-Comparison Study

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 10 August 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.629295 Early Surveillance and Public Health Emergency Responses Between Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Avian Influenza in China: A Case-Comparison Study Tiantian Zhang 1,3†, Qian Wang 2†, Ying Wang 2, Ge Bai 2, Ruiming Dai 2 and Li Luo 2,3,4* 1 School of Social Development and Public Policy, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2 School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 3 Key Laboratory of Public Health Safety of the Ministry of Education and Key Laboratory of Health Technology Assessment of the Ministry of Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 4 Shanghai Institute of Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China Background: Since the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been a worldwide pandemic, the early surveillance and public health emergency disposal are considered crucial to curb this emerging infectious disease. However, studies of COVID-19 on this Edited by: Paul Russell Ward, topic in China are relatively few. Flinders University, Australia Methods: A case-comparison study was conducted using a set of six key time Reviewed by: nodes to form a reference framework for evaluating early surveillance and public health Lidia Kuznetsova, University of Barcelona, Spain emergency disposal between H7N9 avian influenza (2013) in Shanghai and COVID-19 in Giorgio Cortassa, Wuhan, China. International Committee of the Red Cross, Switzerland Findings: A report to the local Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China, for *Correspondence: the first hospitalized patient was sent after 6 and 20 days for H7N9 avian influenza and Li Luo COVID-19, respectively. -

High-Throughput Human Primary Cell-Based Airway Model for Evaluating Infuenza, Coronavirus, Or Other Respira- Tory Viruses in Vitro

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN High‑throughput human primary cell‑based airway model for evaluating infuenza, coronavirus, or other respiratory viruses in vitro A. L. Gard1, R. J. Luu1, C. R. Miller1, R. Maloney1, B. P. Cain1, E. E. Marr1, D. M. Burns1, R. Gaibler1, T. J. Mulhern1, C. A. Wong1, J. Alladina3, J. R. Coppeta1, P. Liu2, J. P. Wang2, H. Azizgolshani1, R. Fennell Fezzie1, J. L. Balestrini1, B. C. Isenberg1, B. D. Medof3, R. W. Finberg2 & J. T. Borenstein1* Infuenza and other respiratory viruses present a signifcant threat to public health, national security, and the world economy, and can lead to the emergence of global pandemics such as from COVID‑ 19. A barrier to the development of efective therapeutics is the absence of a robust and predictive preclinical model, with most studies relying on a combination of in vitro screening with immortalized cell lines and low‑throughput animal models. Here, we integrate human primary airway epithelial cells into a custom‑engineered 96‑device platform (PREDICT96‑ALI) in which tissues are cultured in an array of microchannel‑based culture chambers at an air–liquid interface, in a confguration compatible with high resolution in‑situ imaging and real‑time sensing. We apply this platform to infuenza A virus and coronavirus infections, evaluating viral infection kinetics and antiviral agent dosing across multiple strains and donor populations of human primary cells. Human coronaviruses HCoV‑NL63 and SARS‑CoV‑2 enter host cells via ACE2 and utilize the protease TMPRSS2 for spike protein priming, and we confrm their expression, demonstrate infection across a range of multiplicities of infection, and evaluate the efcacy of camostat mesylate, a known inhibitor of HCoV‑NL63 infection. -

Astrovirus-Like, Coronavirus-Like, and Parvovirus-Like Particles Detected in the Diarrheal Stools of Beagle Pups

Archives of Virology Archives of Virology 66, 2t5--226 (1980) © by Springer-Verlag 1980 Astrovirus-Like, Coronavirus-Like, and Parvovirus-Like Partieles Detected in the Diarrheal Stools of Beagle Pups By F. P. WILLIAMS, JR. Health Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.A. With 5 Figures Accepted May 26, 1980 Summary Astrovirus-like, coronavirus-like, and parvovirus-like particles were detected through electron microscopic (EM) examination of loose and diarrheal stools from a litter of beagle pups. Banding patterns obtained from equilibrium centrifuga- tions in CsC1 supported the EM identification. Densities associated with the identified particles were : 1.34 g/ml for astrovirus, 1.39 g/ml for "full" parvovirus, and 1.24--1.26 g/ml for "typical" coronavirus. Convalescent sera from the pups aggregated these three particle types as observed by immunoelectron microscopy (IEM). Only coronavirus-like particles were later detected in formed stools from these same pups. Coronavirus and parvo-likc viruses arc recognized agents of canine viral enteritis, however, astrovirus has not been previously reported in dogs. Introduction A number of virus-like particles detected in fecal material by electron micro- scopy (EM) have been found to manifest sufficiently distinct morphology to warrant individual classification. Such readily identified agents include: rota- virus (11), coronavirus (30), adenovirus (12), ealieivirus (20), and possibly-mini- reo/rotavirus (23, 29). Astrovirus, another characteristic agent identified by EIM, was originally associated with infantile gastroenteritis (18, 19). Subsequent investigations confirmed the identification of this agent in stools of newborns with acute non- bacterial gastroenteritis (16), and in outbreaks of gastroenteritis involving chil- dren and adults (2, 15). -

Prevent Worker Exposure to Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Prevent Worker Exposure to Coronavirus (COVID-19) The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, spreads from person-to-person, primarily through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. The virus is also believed to spread by people touching a surface or object and then touching one’s mouth, nose, or possibly the eyes. Employers and workers should follow these general practices to help prevent exposure to coronavirus: Frequently wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If soap and running water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub that contains at least 60% alcohol. Avoid touching your eyes, nose, or mouth with unwashed hands. Avoid close contact with people who are sick. Employers of workers with potential occupational exposures to coronavirus should follow these practices: Assess the hazards to which workers may be exposed. Evaluate the risk of exposure. Select, implement, and ensure workers use controls to prevent exposure, including physical barriers to control the spread of the virus; social distancing; and appropriate personal protective equipment, hygiene, and cleaning supplies. For the latest information on the symptoms, prevention, and treatment of coronavirus, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coronavirus webpage. For interim guidance and other resources on protecting workers from coronavirus, visit OSHA’s COVID-19 webpage. OSHA issues alerts to draw attention to worker safety and health issues and solutions. 2020 3 0 - 9 398 • osha.gov/covid-19 • 1-800-321-OSHA (6742) • @OSHA_DOL OSHA OSHA . -

S-Acylation of Proteins of Coronavirus and Influenza Virus

pathogens Article S-Acylation of Proteins of Coronavirus and Influenza Virus: Conservation of Acylation Sites in Animal Viruses and DHHC Acyltransferases in Their Animal Reservoirs Dina A. Abdulrahman 1,†, Xiaorong Meng 2,† and Michael Veit 2,* 1 Department of Virology, Animal Health Research Institute (AHRI), Giza 12618, Egypt; [email protected] 2 Institute of Virology, Veterinary Faculty, Free University Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript. Abstract: Recent pandemics of zoonotic origin were caused by members of coronavirus (CoV) and influenza A (Flu A) viruses. Their glycoproteins (S in CoV, HA in Flu A) and ion channels (E in CoV, M2 in Flu A) are S-acylated. We show that viruses of all genera and from all hosts contain clusters of acylated cysteines in HA, S and E, consistent with the essential function of the modification. In contrast, some Flu viruses lost the acylated cysteine in M2 during evolution, suggesting that it does not affect viral fitness. Members of the DHHC family catalyze palmitoylation. Twenty-three DHHCs exist in humans, but the number varies between vertebrates. SARS-CoV-2 and Flu A proteins are acylated by an overlapping set of DHHCs in human cells. We show that these DHHC genes also exist in other virus hosts. Localization of amino acid substitutions in the 3D structure of DHHCs provided Citation: Abdulrahman, D.A.; Meng, no evidence that their activity or substrate specificity is disturbed. We speculate that newly emerged X.; Veit, M. S-Acylation of Proteins of CoVs or Flu viruses also depend on S-acylation for replication and will use the human DHHCs for Coronavirus and Influenza Virus: that purpose. -

Fact Sheet- Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

FACT SHEET: The Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Will Deliver $350 Billion for State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Governments to Respond to the COVID-19 Emergency and Bring Back Jobs May 10, 2021 Aid to state, local, territorial, and Tribal governments will help turn the tide on the pandemic, address its economic fallout, and lay the foundation for a strong and equitable recovery Today, the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced the launch of the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, established by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, to provide $350 billion in emergency funding for eligible state, local, territorial, and Tribal governments. Treasury also released details on how these funds can be used to respond to acute pandemic response needs, fill revenue shortfalls among these governments, and support the communities and populations hardest-hit by the COVID-19 crisis. With the launch of the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, eligible jurisdictions will be able to access this funding in the coming days to address these needs. State, local, territorial, and Tribal governments have been on the frontlines of responding to the immense public health and economic needs created by this crisis – from standing up vaccination sites to supporting small businesses – even as these governments confronted revenue shortfalls during the downturn. As a result, these governments have endured unprecedented strains, forcing many to make untenable choices between laying off educators, firefighters, and other frontline workers or failing to provide other services that communities rely on. Faced with these challenges, state and local governments have cut over 1 million jobs since the beginning of the crisis. -

SARS and H5N1

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2006; 36:245–248 PAPER © 2006 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Newly emerged respiratory infections – SARS and H5N1 1CM Chu, 2KWT Tsang 1United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, 2University Department of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR ABSTRACT Two newly emerged respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV and the highly Published online April 2006 pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 virus, have arisen in Asia at the turn of the millennium. They both have the potential to cause global pandemics, facilitated by Correspondence to CM Chu, modern high-speed international transportation. Molecular studies suggest that Department of Medicine and SARS-CoV could be transmitted to humans from civet cats and other game Geriatrics, United Christian animals consumed as a culinary delicacy. The H5N1 virus appears to be endemic Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, HONG KONG in bird and poultry populations in Asia, with sporadic transmission to humans. Both SARS-CoV and H5N1 begin with a non-specific influenza-like illness, tel. (852) 3513 4822 progressing rapidly to severe pneumonia and ARDS. Although various antiviral and immunomodulatory agents have been tried, or postulated to be useful, none has fax. (852) 3513 5548 been proven effective by RCTs. Treatment remains supportive and the mortalities are high for both conditions. No vaccine has yet been approved for either e-mail [email protected] infection, although infection control measures have been found to be effective in hospital settings. While all known chains of person-to-person transmission of SARS were broken in July 2003, a few small pockets of outbreak have occurred since, related to laboratory accidents and contact with game animals. -

Safer Sex and COVID-19

Safer Sex and COVID-19 Safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines allow us to more safely engage in relationships, sex and everything in between! Practice these strategies to protect yourself and your partners from COVID-19. Know how COVID-19 spreads The virus spreads by infected saliva, mucus, or respiratory particles being inhaled or entering the eyes, nose, or mouth. • The virus can spread during sex since sex can involve close heavy breathing and contact with saliva. • There is no evidence the virus spreads through semen or vaginal fluid, though the virus has been found in the semen of people who have COVID-19. • The risk of spreading the virus through feces (poop) is thought to be low, though the virus has been found in the feces of people who have COVID-19. Research is needed to know if the virus can spread through sexual activities involving oral contact with feces (such as rimming). Tips for reducing the risk of getting and spreading COVID-19 during sex Get vaccinated! • COVID-19 vaccination allows for safer interactions inside and outside the bedroom. It is the best way to protect yourself and unvaccinated partners from COVID-19 illness, hospitalization and death. • Visit vaccinefinder.nyc.gov or call 877-VAX-4NYC (877-829-4692) to find a vaccination site. Vaccination is free and appointments are not needed at many sites. • People who are fully vaccinated (meaning at least two weeks since they got a single-dose vaccine or the second dose of a two-dose vaccine) can go on dates, make out and have sex without face coverings and other COVID-19 precautions. -

Coronavirus: Detailed Taxonomy

Coronavirus: Detailed taxonomy Coronaviruses are in the realm: Riboviria; phylum: Incertae sedis; and order: Nidovirales. The Coronaviridae family gets its name, in part, because the virus surface is surrounded by a ring of projections that appear like a solar corona when viewed through an electron microscope. Taxonomically, the main Coronaviridae subfamily – Orthocoronavirinae – is subdivided into alpha (formerly referred to as type 1 or phylogroup 1), beta (formerly referred to as type 2 or phylogroup 2), delta, and gamma coronavirus genera. Using molecular clock analysis, investigators have estimated the most common ancestor of all coronaviruses appeared in about 8,100 BC, and those of alphacoronavirus, betacoronavirus, gammacoronavirus, and deltacoronavirus appeared in approximately 2,400 BC, 3,300 BC, 2,800 BC, and 3,000 BC, respectively. These investigators posit that bats and birds are ideal hosts for the coronavirus gene source, bats for alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus, and birds for gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. Coronaviruses are usually associated with enteric or respiratory diseases in their hosts, although hepatic, neurologic, and other organ systems may be affected with certain coronaviruses. Genomic and amino acid sequence phylogenetic trees do not offer clear lines of demarcation among corona virus genus, lineage (subgroup), host, and organ system affected by disease, so information is provided below in rough descending order of the phylogenetic length of the reported genome. Subgroup/ Genus Lineage Abbreviation