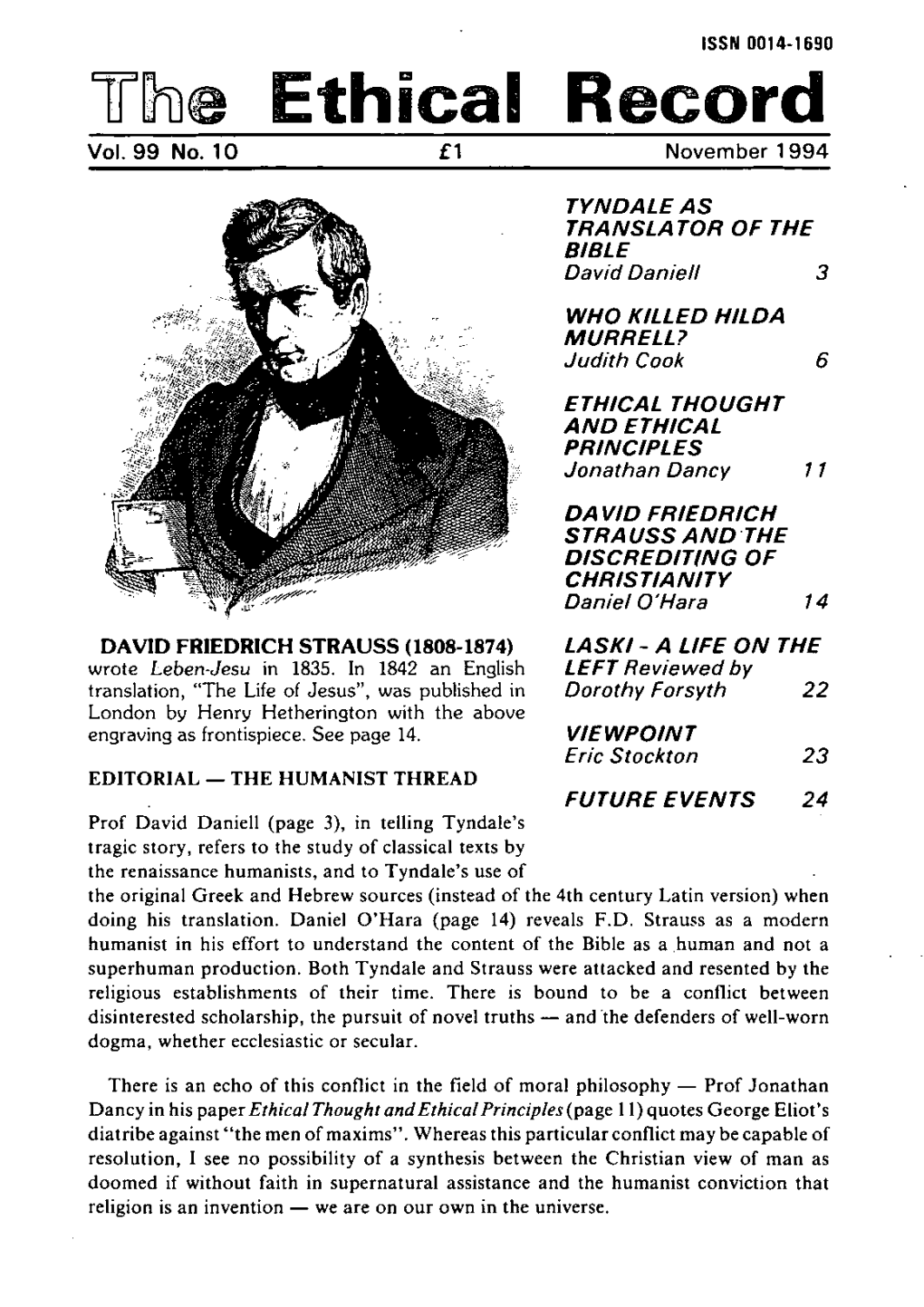

The Ethical Record Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrekin Syndicalists

fi What We Stand For € The "free" world is not free; the "communist" norld i s not communist.' he' regect' both: one is becoming totalitarian; the other is already so. Their current power struggle leads inexorably to atomic war and the probable destruction of the human race. We charge that both systems engender servi- tude. Pseudo-freedom based on ec ' slavery is no better than pseudo-freedome onomic based on political slavery- The monopoly of power which is the state must .be eliminated. Government itself, as-well “as its» underlying ins ti tutions, perpetuates war, oppression, corruption, exploitation, and misery. We advocate a world-wide society of communi- tiee andA councils~ ' based on coo eration and" free agreement from the bottom-C Ffed‘eralism) inetead of coercion and domination from the top i-*(centralism). Regimentation' l rof people must _be replaced by regulation of things. ,_ -- i Freedom~witbout socialism is chaotic, but so- - cialism without freedom is-despotic- Lib- ertarianism is free socialism. 1 -3- I : The arrogance-of zmo-ontested power. Recently three men, arrested almost by mistake, under suspic- ion, were found first to be falsely posing as police. They were carrying a false police warrant card. Normally that would suffice to get them locked up. But that was not all. Police investigation showed that they had at home a number of other police warrant cards, of identific- ation cards for security services and for varying The Arrogance of uncontested power government ministries under a number of aliases. - Laurens Otter It also emerged that they had a number of confidential btate published: Wrekin Syndicalists, documents, from the Ministry of Defence and other Govern- (formerly Wrekin Libertarians mental departments; ans a number of other papers falsely L L College Farm House, purporting to be such state documents; and that they were lwellington, Salop. -

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources Available at Oswestry Library

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources available at Oswestry Library 14/01/2019 1 Revision 6 Contents Parish Registers & Monument Inscriptions 3 Trade Directories 33 Shops and Occupants Living In Oswestry 35 Electoral Registers 43 Newspapers, Magazines & Periodicals held in Oswestry Library 47 BCA Hard Copy Newspapers held in Guild Hall 47 Newspapers Alphabetical Index to Marriages & Deaths & Subject Cards 51 Parish and Village Magazines & Newsletters 53 Quarter Sessions 55 Oswestry Town Council Archive 55 Maps and Plans Field Name Maps 56 Ordnance Survey Maps 58 Other Maps 58 Tithe Apportionments 58 Printed Material 58 Photographs, Postcards and Prints 59 Parish Packs 59 Local Places Information Folders 59 Local People Information Folders 68 Media List 69 Welsh Collection 70 Fees for Weddings and Funerals circa 1768 70 14/01/2019 2 Revision 6 REGISTERS An index to Parish, Non-conformist and Roman Catholic Registers & Monumental Inscriptions held at Oswestry Library can be found below. The index indicates whether the item is available in printed form and / or on microfiche and/or digital. Parish: The registers for Oswestry and its neighbouring parishes in England and Wales are available not only in printed volumes held in the rolling stack at the library and on microfiche, but have also been put online by FindMyPast up to the year 1900 and are free to view on all library computers. Non-conformist: To find out if a non-conformist chapel or church existed in a particular area consult one of the following held in the rolling stack: Kelly's Directory, which lists chapels and Roman Catholic Churches in each parish; b) Victoria County History of Shropshire Vol. -

The Development of the British Conspiracy Thriller 1980-1990

The Development of the British Conspiracy Thriller 1980-1990 Paul S. Lynch This thesis is submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January 2017 Abstract This thesis adopts a cross-disciplinary approach to explore the development of the conspiracy thriller genre in British cinema during the 1980s. There is considerable academic interest in the Hollywood conspiracy cycle that emerged in America during the 1970s. Films such as The Parallax View (Pakula, 1975) and All the President’s Men (Pakula, 1976) are indicative of the genre, and sought to reflect public anxieties about perceived government misdeeds and misconduct within the security services. In Europe during the same period, directors Costa-Gavras and Francesco Rosi were exploring similar themes of state corruption and conspiracy in films such as State of Siege (1972) and Illustrious Corpses (1976). This thesis provides a comprehensive account of how a similar conspiracy cycle emerged in Britain in the following decade. We will examine the ways in which British film-makers used the conspiracy form to reflect public concerns about issues of defence and national security, and questioned the measures adopted by the British government and the intelligence community to combat Soviet subversion during the last decade of the Cold War. Unlike other research exploring espionage in British film and television, this research is concerned exclusively with the development of the conspiracy thriller genre in mainstream cinema. This has been achieved using three case studies: Defence of the Realm (Drury, 1986), The Whistle Blower (Langton, 1987) and The Fourth Protocol (MacKenzie, 1987). -

The Hilda Murrell Murder

A Thorn in Their Side The Hilda Murrell murder Robert Green with Kate Dewes New Zealand: Rata Books, 2011; 210 pp., index, photographs, p/b, 40 NZ dollars Once upon a time I used to know something about the Hilda Murrell case. At any rate, a piece about it without an author, therefore by me, is in Lobster 27. Seventeen years on from that piece, as I began reading Robert Green’s account of the death of his aunt (who was a kind of surrogate mother, his biological mother dying when he was 19), I would summarise my knowledge thus: she was murdered; it might have been about her opposition to nuclear power; or, more likely, the connection to the author, who had been a naval officer with some connection to the sinking of the Argentine ship the General Belgrano; recently someone who was 16 years old at the time was convicted of the murder, basically on DNA evidence. Which is to say I had remembered so little that I was almost new to the story. First, Green describes Hilda Murrell in some detail and takes us through his experience of the event and its immediate aftermath: the police investigation and the autopsy. He tell us that, on hearing of her death, he immediately suspected she had been ‘rubbed out’, as he puts it. This is very striking indeed. Not a politico, two years after leaving the Navy – and senior, too, a Commander – his response to hearing of the murder of his aunt isn’t, ‘Oh dear, I always knew living alone in rural isolation might go bad for her. -

Statewatch Bulletin

Statewatch bulletin Vol 4 no 2 March-April 1994 IN THIS ISSUE: * France: new penal code * Europol HQ opened * Operation Jackpot * TUC march against racism * Justice & Interior Ministers meeting * New UK secrecy definitions * Germany: `Internal security' laws IMMIGRATION the appropriateness' of holding `distressed, despondent and in some cases desperate' asylum seekers in Pentonville prison. Up to 65 Wave of hunger strikes immigration prisoners are held in Pentonville at any one time. In a report released on 22 March he condemned Pentonville's health A wave of hunger strikes has swept through prisons and detention care centre as rundown, cramped, dirty and unfit for patients. centres across Britain as asylum seekers protest against their In the face of the recent wave of protests, the Home Office has detention, their inhuman treatment and deportations which have resorted to its usual strategy of dispersal, and of punishing resulted in death. detainees in detention centres by moving them to prison. However, Since the end of February, when ten north Africans were released this time the strategy seems to have had the opposite effect to that from Pentonville after ten days of an indefinite hunger strike, the intended, by fanning the flames of protest and spreading the strike number of asylum seekers on hunger strike grew to over 200 in to hitherto unaffected prisons. Thus it was reported towards the end mid-March. Over 100 were held in Campsfield, the new of March that several of the prisoners at Winson Green had joined immigration detention centre at Kidlington, outside Oxford, which the asylum seekers sent from Campsfield in their hunger strike. -

Journal of Parapolitics Lobster 95 Is Edited and Published by My Apologies for the Long Delay in Lobster 95 Individual Issues: Stephen Dorril

THE FACE OF THE BRITISH GLADIO? (The 'running man' of the Hilda Murrell murder) NEO FASCISTS. GREEN SURVEILLANCE IRELAND, SPOOKS, MI5 A2 AND THE LABOUR MOVEMENT Journal of Parapolitics Lobster 95 is edited and published by My apologies for the long delay in Lobster 95 individual issues: Stephen Dorril. publishing this issue. I am still in the £2.50 (inc p&p) process of finishing my history of MI6 and 135 School Street everything takes much longer than Lobster 95 subscriptions (forfour issues): Netherthong expected. We also had some technical £8.00 (inc p&p) Holmfirth difficulties with the scanner which put West Yorkshire everything behind schedule. Fortunately, Cheques payable to S Dom.1 ' HD7 2YB I now have an abundance of materials for the next issue -watch out for the ground- Lobster 95 USICanadalEurope: £12.00 Tel: 01484 681388 breakingnew material on Wilson, Maxwell and the Scottish League for European Cash (dollars accepted), International 1 September 1995 Freedom. money orders, cheques drawn on UK bank (foreign cheques cost too much to convert The promised Lobster 95 meeting is still on into Sterling). but not until the beginning of next year when the book is out of the way - which gives me time to organise it. I have a good venue in Huddersfield, whichis central for lots of people, and a number of major LOBSTER 95 speakers. The topics so far are 'Gladio', the SPECIAL OFFER next election and the inevitable smear campaign, and the new MI5 agenda. I would welcome additional suggestions. PAPERBACK COPY OF I havebeenforced to raiseprices,primarily because of the post and packing costs - no one makes money out of this type of SMEAR! enterprise. -

Wrekin Syndicalists

_—. __7_ _ _ 7 _ ?____%_’,____________ t . er‘ "T | (Z 3§?l~<;",.;- ..,,.,'<.1‘ 1"“ L. '* ii. _1 Nevertheless it has to be of interest to workers when governments treat their normal procedures with disdain. Thatcher, when speaking in France, claimed ' L that it was not the French Revolution but_the English one, that introduced demr ocracy to the world. Yet, though the alleged gains, (whether of Cromwell or William of Orange,> are always described in official constitutional history, as the introduction of respect for the rule of law, and the limitation of govern- LAW 8: HYPOCRISY mental powers; she has persistently & flagrantly flouted the law, & identifiedr the interests of the state with those of the governing party. * Ho doubt this belief in the rule of law has always been a myth; history is full of occasions when it has been flouted, but until now there has always been It cannot have escaped the notice of even the least political that we have a an attempt to ensure that the pretense is kept up. We need to know why govern- government whose watch~words are law & order. That when workers strike they ment is prepared to dispense with these essentials of the democratic myth. The are harangued about ignoring the law, (often a law conveniently just passed, for answer lies in the economic interests the governmemnt serves. the very purpose of crippling industrial organizations, & it is interesting that when — as in the current example of the N.U.R. — the union observes the law so This government periodically claim to have rolled back the frontiers of soc- made, and appears to be winning, an howl goes up amongst government supporters ialism, & since the Labour Party occasionally pays lip service to socialism, & for the law to be yet further changed.) The same tones of judicial superiority wouldn't like to admit that it has never moved in this direction, no one points have been used against Greenham women and other protestors, though punctuated by out that there were never any such frontiers to role back. -

BC Publishing Keeps Growing After D&M Schmozzle

25 YOUR GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS th Anniversary FREE Year TheThe AncientAncient Mariner,Mariner, BC forfor realreal PAGES 20-21 BOOKWORLD NEWNEW DIGS!DIGS! BCBC publishingpublishing keepskeeps growinggrowing afterafter D&MD&M schmozzleschmozzle See pages #40010086 7, 8, 10 11, 16, 19 GREEMENT A AIL M Heidi Scheifley and Moreka Jolar, authors of Hollyhock: Garden to Table. UBLICATION P PENNY APPLE PENNY PHOTOGRAPHY CONFIDENT MINING LONG BLACK EXPOSÉ BEACH LIKE THEM CANADA, NEW BAD BEFORE THE LANDMARK POETRY GUY ABROAD P. 2 7 TOURISTS P. 16 ANTHOLOGY P. 3 8 VOL. 27 • NO. 1 Storma Sire, SPRING 2013 ALERT BAY’S CRUSADING MATRIARCH P. 23 The Great Black North 2 BC BOOKWORLD SPRING 2013 3 BC BOOKWORLD SPRING 2013 PEOPLE At 77, W.P. Kinsella topped a recent poll conducted by The Province to name the province’s most popular writer. He also recently received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal (“I’m still not sure why.”) and was inducted into the Canadian Sensational Victoria: Bright Baseball Hall of Fame as a baseball writer. Now there are plans Lights, Red Lights, Murders, afoot for a musical version of his story Shoeless Joe, the basis Ghosts & Gardens (Anvil Press $24) for the movie Field of Dreams. As well, Willie Steele has pub- by Eve Lazarus lished a new critical study, A Member of the Local Nine: Base- ball and Identity in the Work of W. P. Kinsella. Not bad for a guy who used to manage a pizza joint in Victoria. BCTOP* SELLERS The Canadian Pacific’s Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway: The CPR WP Kinsella, Steam Years, 1905–1949 1997 (Sono Nis $39.95) by Robert D. -

Breaking Free from Nuclear

11 00 tt hh aa nn nn uu aa ll FRANK K. KELLY LECTURE ON HUMANITY’S FUTURE BBrreeaakkiinngg FFrreeee FFrroomm nnuucclleeaarr DDeetteerrrreennccee COMMANDER roBert green (Royal Navy, Ret.) building a more peaceful world free of nuclear weapons Frank K. Kelly Lecture ON HUMANITY’S FUTURE he Frank K. Kelly Lecture on Humanity’s Future was established by the Nuclear Age Peace TFoundation in 2002. The lecture series honors the late Frank K. Kelly, a founder and senior vice president of the Foundation, whose vision and compassion are perpetuated through these lectures. Each annual lecture is presented by a distinguished individual to explore the contours of humanity’s present circumstances and ways by which we can shape a more promising future for our planet and all its inhabitants. Mr. Kelly gave the inaugural lecture in 2002 on “Glorious Beings: What We Are and What We May Become.” The lecture presented in this booklet, “Breaking Free from Nuclear Deterrence,” the tenth in the series, was presented by Commander Robert Green (Royal Navy, Ret.) at Santa Barbara City College on February 17, 2011. The 2010 lecture was presented by Ambassador Max Kampelman on “Zero Nuclear Weapons for a Sane and Sustainable World.” The 2009 lecture was presented by Frances Moore Lappé on “Living Democracy, Feeding Hope.” The 2008 lecture was given by Colman McCarthy on “Teach Peace.” The 2007 lecture was delivered by Jakob von Uexküll on “Globalization: Values, Responsibility and Global Justice.” The 2006 lec - ture was presented by Nobel Peace Laureate Mairead Corrigan Maguire on “A Right to Live without Violence, Nuclear Weapons and War.” The 2005 lecture was delivered by Dr. -

The Labour Party, British Intelligence and Oversight, 1979-1994 Lomas, DWB

Party politics and intelligence : the Labour Party, British intelligence and oversight, 1979-1994 Lomas, DWB http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2021.1874102 Title Party politics and intelligence : the Labour Party, British intelligence and oversight, 1979-1994 Authors Lomas, DWB Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/59265/ Published Date 2021 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Intelligence and National Security ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fint20 Party politics and intelligence: the Labour Party, British intelligence and oversight, 1979-1994 Daniel W. B. Lomas To cite this article: Daniel W. B. Lomas (2021) Party politics and intelligence: the Labour Party, British intelligence and oversight, 1979-1994, Intelligence and National Security, 36:3, 410-430, DOI: 10.1080/02684527.2021.1874102 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2021.1874102 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 13 Jan 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 653 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fint20 INTELLIGENCE AND NATIONAL SECURITY 2021, VOL. -

Lobster 75 Summer 2018

www.lobster-magazine.co.uk Summer 2018 • The view from the bridge by Robin Ramsay Lobster Updated 17 May 2018 • Deep Kiss: How the Washington Post missed the biggest Watergate story of all by Garrick 75 Alder • Using the UK FOIA, part II by Nick Must • Hugh who? (Hugh Mooney) by Robin Ramsay • Hilda Murrell and the FOIA by Nick Must • South of the Border by Nick Must • Still thinking about Dallas by Robin Ramsay • Back to the future (again) by Simon Matthews • Anna Raccoon and the dawn of Savilisation by Andrew Rosthorn Book Reviews • The Darkest Sides of Politics, Parts I & II, by Jeffrey M Bale reviewed by Robin Ramsay • What Did You Do During the War? The Last Throes of the British Pro-Nazi Right, 1940-45, by Richard Griffiths reviewed by David Sivier • My Life, Our Times, by Gordon Brown reviewed by John Newsinger • Mad men? Marketing the Third Reich: Persuasion, Packaging and Propaganda, by Nicholas O’Shaughnessy reviewed by Colin Challen • Unwinnable: Britain’s War in Afghanistan, 2001-2014, by Theo Farrell reviewed by John Newsinger • Farming, Fascism and Ecology: A Life of Jorian Jenks, by Philip M. Coupland reviewed by David Sivier • Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation, by Liz Featherstone, reviewed by Colin Challen www.lobster-magazine.co.uk The View from the Bridge Robin Ramsay Thanks to Nick Must (in particular) and Garrick Alder for editorial and proof-reading assistance with this issue. * new * The higher bullshit There has been more well-intentioned nonsense written by academics about the assassination of JFK than any other subject I have looked at. -

Campaigners for Peace

peace & justice Campaigners for peace In a leafy Christchurch suburb Tui Motu recently visited the home of Kate Dewes and Rob Green, also the headquarters of the Peace Foundation’s Disarmament & Security Centre (DSC). Kate and Rob have a common passion for world peace and nuclear disarmament. This joint quest has brought them together personally. Rob’s story Buccaneer nuclear-strike jet n January 1991, at the height of squadron based on the aircraft Ithe first Gulf War, Rob Green was carrier HMS Eagle. Their invited to address an antiwar rally assigned cold war target was a of some 20,000 people in Trafalgar military airfield on the outskirts Square, London. Here was he, a retired of Leningrad, Russia, now Commander in the Royal Navy, at known by its original name, the foot of Admiral Nelson’s column St Petersburg. They had the speaking out against the validity of the capability of dropping a 100 nuclear deterrent. It was the climax of kiloton thermonuclear bomb a long journey of disillusion and the close to a civilian population discovery of a new faith. in one of the world’s most beautiful ancient capital cities. Five days later the futility of that “I accepted without question deterrent was amply displayed when an élite role with my pilot as Iraq launched its first SCUD ballistic ‘nuclear crew’”, Rob writes. missile attack against Israel. The missiles fell on Tel Aviv, Israel’s second Later he was switched to city. A nuclear state had been attacked antisubmarine helicopters. by a non-nuclear one. The Americans Their role was to defend the responded by ordering air attacks on aircraft carrier Ark Royal from the SCUD launch sites, but the United possible Soviet submarine States could do nothing to prevent attack.