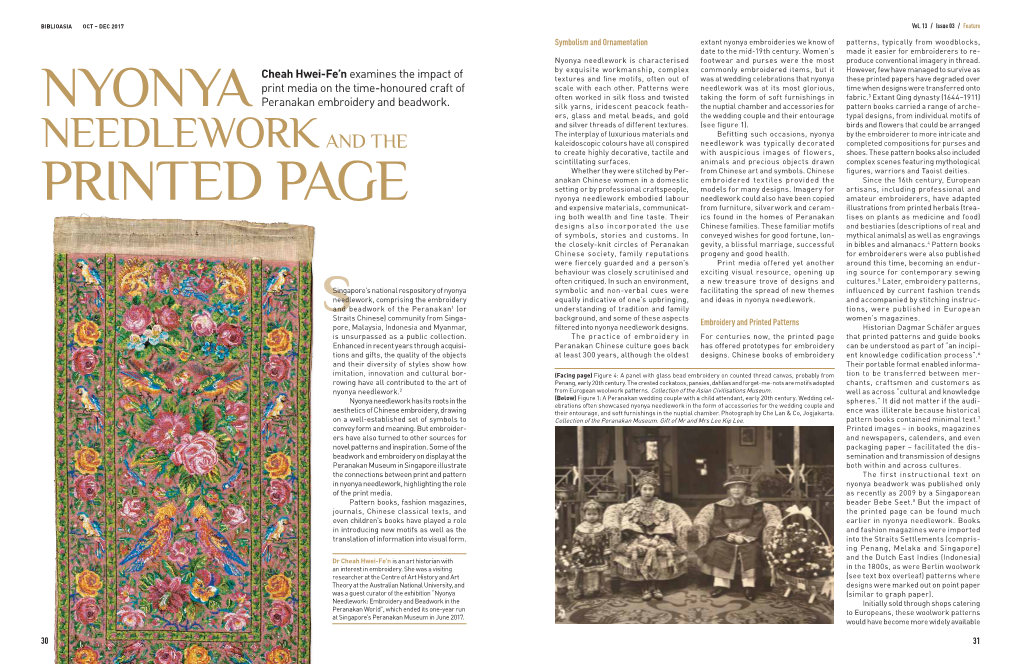

Nyonya Embroideries We Know of Patterns, Typically from Woodblocks, Date to the Mid-19Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-H Crocheting Project Member Guide

4-H Crocheting Project Member Guide Crocheting is one of the oldest needlework arts. To crochet means to form yarn or thread into a fabric using a hook. Its name comes from the French word croche, meaning “hook.” The crochet hook was one of many tools first used to make delicate lace. As time went on, more stitches and designs came into being, and crocheting became a separate art. Crocheting appeals to many people because it can be used to make a variety of creations, such as scarves, caps, vests, sweaters, purses, belts, lace, doilies, tablecloths, afghans, pillow covers, and bedspreads. In the 4-H Crocheting Project, you can learn to: • Crochet articles for yourself and others • Select, use, and care for crocheting tools • Work and share with others in your club • Keep simple records of your project and activities The 4-H Crocheting project is divided into six phases. Skills to learn and suggested articles to make are on page 2. Your club leader will teach you how to do basic crochet stitches and help you find patterns to use as you learn. When you reach the advanced phases, you’ll need to choose patterns from a variety of pattern books, needlework books, and magazines. You can find these at newsstands, notions counters, fabric stores, or specialty shops that sell yarn and thread. If you want to show others what you learn in the Crocheting project, check with your leader about exhibiting articles at fairs or other community events. If you make an article to wear, you might like to model in your county 4-H fashion revue. -

October 2018

YMOCT18Cover.FINAL:Layout 1 11/1/18 5:21 PM Page CV1 CAN YOU KEEP BE THE LISTEN A SECRET? CHANGE UP! Protect shared The retail Podcasts get you information with landscape is inside the heads of a nondisclosure changing your customers— agreement. quickly.Are literally. you ready? OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2018 2019: A YARN ODYSSEY FREE COPY DelicatE wslavender eucalyptus grapefruit unscented jasmine h p teatmen o you in ashable YMN1018_Eucalan_AD.indd 1 10/23/18 12:49 PM Plymouth Yarn Pattern #3272 Drape Front Cardi Plymouth Yarn Pattern #3272 Drape Front Cardi 60% Baby Alpaca 25% Extrafine Merino 15% Yak 60% Baby Alpaca 25% Extrafine Merino 15% Yak WWW.PLYMOUTHYARN.COMWWW.PLYMOUTHYARN.COM YMN1018_Plymouth_AD.indd 1 10/23/18 12:48 PM YMOCT18EdLetter.FINAL:Layout 1 10/31/18 2:24 PM Page 2 EDITOR’S LETTER Looking Back, Looking Forward ROSE CALLAHAN Where were you five years ago? It was the fall of 2013. Some of you may not have even owned your business in the yarn industry yet, while others of you had been at it for well over 20 years. Some of you had not yet become parents; others were close to becoming empty nesters. A lot can change in five years, but of course, a lot can stay the same. Five years ago, Yarn Market News made a change. Because of dwindling advertising dollars, we announced that we would be publishing three issues a year instead of five. And this issue marks our first all-digital issue, born out of both a desire to go green and to help the magazine’s struggling bottom line. -

Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop

Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop An At-Home Program GSCCC Senior Textile Artist Badge Workshop (At-Home) • When you see fabrics, yarn, or string off all colors and textures what do you think of? Do you envision all of the things you could create? Let’s turn those visions into reality! Program Outline Materials: - Computer - Internet access - Materials for craft of choice Step 1: Choose your textile art There are a number of textile arts in the world from macramé to crocheting to quilting and much more. In this step you will be doing some research to learn about a textile art that you find interesting and that you would like to learn. Some of the most common textile arts are macramé, embroidery, cross-stitch, needlework, knitting, crocheting, weaving, and quilting. Do some research to find out about these or other textile arts. Below are some helpful links to start with. Here are a few links to get your search started – crochet, macramé, embroidery, weaving. Click here to see what some current textile artists are doing. Step 2: Find your tools and materials Now that you have chosen your art, you need to gather materials. Crocheting needs crochet hooks and yarn. Embroidery needs needles, embroidery floss, hoops, and fabric. Do some research about what you will need for your chosen textile art form. What all is involved? Do you know anyone who already has the supplies? Would they be willing to lend you some materials? Below are some great resources to learn about materials needed for the most common textile arts. -

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

Working with Neon Rays Added Karen Chrissinger As a Teacher

June 2017 A Message from Jill In this Issue: On October 1, 2009, I took a big step in my and my family’s life - I A Message from Jill purchased Louise’s Needlework. Being an owner of a small business is one of the hardest yet most fulfilling jobs there is. I love the challenge of Yeah….that stitch! growing Louise’s every year and we have come so far yet there is still more Karen Chrissinger discusses the basic types of stitches and growing to do. Our move has been one of the best changes we made. We how they are worked. love our space, light and parking. In fact we wish we had more space than we have now! We have added new thread lines and continue to grow Classes others. Don’t miss out on a wonderful new class beginning soon at Louise’s. We have had great success with our clubs and will continue to add new and exciting ones in the near future. New classes have been added on A Few of Our Newest Arrivals Thursdays and we have hosted Laura Taylor (who will be back in 2018), Canvases just added – and will be hosting Kelly Clark in September. available in the store and online. Even employees have changed. We have Working with Neon Rays added Karen Chrissinger as a teacher. If you Diane Snyder gives several haven’t taken a class from her you should. helpful hints on working with this beautiful, but sometimes Karen has spread her love of needlepoint to frustrating, ribbon. -

Annual Report 2009 – 2010

Summer 2010 O L D S T U R B R I D G E Special Annual VILLAGE Report Edition Visitor 2009-2010 2009--2010 Building On Our Strengths Firing Up the Kiln Quilts from the OSV Collection Summer Events a member magazine that keeps you co m i n g b a c k Old Sturbridge Village, a museum and learning resource of 2009 Building On Our Strengths New England life, invites each visitor to find meaning, pleasure, 2010 Old Sturbridge Village Annual Report relevance, and inspiration through the exploration of history. A message from our President and CEO Jim Donahue to our V I S I T O R magazine. Old Sturbridge Village is a fitting We hope that you will learn new things and come to visit the Village soon. There is always something fun to do at place to learn a history lesson in how to deal with Welcome O l d S T u R b ri d g E V I l l a g E . challenging times and still move forward and prosper in the face of great adversity. That lesson Volume l, No. 1 Summer 2010 Special Annual Report Edition definitely played out this year during one of the Interpreter Nancy Garder wears a 1830s-style summer bonnet. On the Cover: most difficult economic periods this country has In This Issue: 2009–2010 Annual Report experienced over the last 60 years. 1 Building On Our Strengths A Message from our President and CEO Jim Donahue President and CEO Jim Donahue Vice President of Marketing and 7 Chairman’s Letter Communications Ann Lindblad Just knowing that generations before us Communications Coordinator Susie Bonta Design Yellow Inc. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

All About Macramé History of Macramé

August 2019 Newsletter All about Macramé For August we thought we would ring the changes and dedicate this edition of the newsletter to a fibre art that was popular in the 1970’s and 80’s for making wall hangings and potholders but which has recently made a resurgence in fibre art. Some customers have also found that the weaversbazaar cotton and linen warps are ideally suited to macramé. So we have all been having a go. Dianne Miles, one of the weaversbazaar tutors, has extensive experience in Macramé and has designed a one day course to show how the techniques can be incorporated into Tapestry for stunning effect – more details below. So we would like to show you some of the best work going on and introduce you to some of the cross overs with other textile art. History of Macramé The earliest recorded macramé knots appear in decorative carvings of the Babylonians and Assyrians. Macramé was introduced to Europe via Spain during its conquest by the Moors and the word is believed to derive from a 13th century Arabic weavers term meaning fringe as the knots were used to turn excess yarn into decorative edges to finish hand woven fabrics. Probably introduced to England by Queen Mary in the late 17th century it was also practiced by sailors who made decorative objects (such as hammocks, belts etc.) whilst at sea thereby disseminating it even further afield when they sold their work in port. It was also known as McNamara’s Lace. The Victorians loved macramé for “rich trimming” for clothing and household items with a favourite book being “Sylvia’s Book of Macramé Lace” which is still available today. -

Authors/Editors Subject

AUTHORS/EDITORS SUBJECT APS VHS video AQS catalogue AQS catalogue DOAK, CAROL paper pieced LARK BOOKS art quilts CAMPBELL-HARDING, VALERIE strip piecing HACKETT, MARY L. landscape HACKETT, MARY L. landscapes FREEMAN, ROLAND quilt history PERRY, ROSILAND & FROLLI, MARY applique SUIT, MARY SUE patchwork ROLFE, MARGARET animal designs SIUDARA, ZYLPHA DVD PORTER, CHRISTINE & DARRA WILLIAMSON small quilts JOHNSTON, ANN dyeing WAGNER, CAROL architectual quilting DONALSDON, JANIE quilting designs BARROW, JODI sq. in a sq. BISHOP, ROBERT patriotic quilts ALDERMAN, BETTY Redwork HECHTLINGER, ALDELAIDE history of quilts MARSTON, G. & CUNNINGHAMJ. flower quilts MARSTON, G. & J. CUNNINGHAM traditional quilts BETTER HOMES & GARDENS collection REGAN, JENNIFER history of quilts GARNAS, VICKI traditional quilts GREEN, MARY (ed) Collection LAWSON, SUZY Amish Quilts JENKINS & GOLDSMITH amish BURNS, ELEANOR Amish Quilts PELLMAN, RACHEL Amish quilts MARSTON, G. & CUNNINGHAM, J. Amish Quilting designs HENNING, BRENDA scrap quilts BUTLER, AMY purse patterns OROYAN, SUSANNA dolls HICKEY, MARY basics BOYCE, ANN applique SIENKIEWICZ, ELLIE applique MERRETT, STEWART applique BUCKLEY, KAREN KAY applique ANDERSON, FAYE applique BASS, CHARLOTTE applique LAURY, JEAN RAY applique TOWNSWICK, JANE hand applique WHITE, TONEE holiday/seasonal WHITE, TONEE applique EICHORN, ROSEMARY art quilts COLLINS, SALLY piecing basics WOLFF, COLETTE manipulating fabric JOYCE, HENRY history of quilts SHAW, ROBERT art quilts JOHNSTON, JACK dolls ROBINSON, CHARLOTTE Collection PIPPEN, -

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni

Basic Blackwork Class – HL Anja Snihová Camarni I’m including in this handout a couple of different ways of explaining “how-to” in blackwork, because not every explanation works for every person. Also, please excuse the crass commercial plugs. I didn’t have time to completely re-write, so pretend that this somebody else’s. Which it is! Anja and MaryAnne are not the same person. <grin> MaryAnne Bartlett is a 21st century woman, making a living by writing and researching, designing and selling blackwork designs and products. Anja Snihova’ was born in the late 14th century and due to the potions that her alchemist husband makes, survived into the early 17th century! Beginning Blackwork Blackwork is a counted thread technique made popular in England in the 1500's by Catharine of Aragon, the Spanish first wife of King Henry VIII of England. It was immortalized in the incredibly detailed portraits done by the court painter, Hans Holbein, whose name is give to the stitch used, which is just a running stitch that doubles back on itself at the other end of its "journey". Blackwork can be anything from a simple line drawing to the complex pattern of #10 below, and on to designs so complex no one seems to know how to do them! It was usually done with silk thread on a white even-weave linen, and despite the name of the technique, was done in every colour of the rainbow, although black was the most popular colour, followed by red and blue. The most peculiar thing about this technique is that, done properly, the design repeats on both the right and wrong sides of the fabric, making it perfect for collars, cuffs, veils and ribbons where both sides need to look nice! Blackwork Embroidery Instructions 1. -

Clothing, Needlework and Quilt Quest

CLOTHING, NEEDLEWORK AND QUILT QUEST All entries in the STEAM Clothing Projects, Shopping in Style, Quilt Quest, Knitting and Crocheting are judged at Conference Judging - Fashion Show Day, Thursday, July 16. These exhibits will not be judged on entry day, Tuesday, July 21. Please bring all wearable exhibits on wire hangers or hangers with a swivel hook ONLY. All exhibits that are not suitable for hanging should be entered in a plastic bag. Wool garments and garments with narrow straps hang better on other hangers, i.e. wooden or notched plastic hangers. As you look at the garment place the hook of the hanger pointing to the left. Use safety pins to fasten skirts, shorts and pants to hangers. Each piece is to be entered on its own hanger. If more than one hanger is used for an entry, fasten hangers belonging to one exhibit together with twist ties or rubber bands. Entry tag placement: as you look at the garment place the entry tag on the right side of the garment and the hook of the hanger to the left. Garments as listed may be made for self or another person. All clothing exhibits must be exhibited at the fair to receive premium. 4-H’ers enrolled in clothing projects should continue their skill development. Once you have exhibited in a higher level, you are not eligible to exhibit in a lower level. Ex: Once you exhibit in STEAM Clothing 2, you are not eligible to exhibit in STEAM Clothing 1. You may enter up to two items per class but must use different patterns. -

Spinning Yarns, Telling Tales About Textiles

News for Schools from the Smithsonian Institution, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Washington, D.C. 20560 SEPTEMBER 1980 Spinning Yarns, Telling Tales about Textiles Textiles Tell Stories: The "Age of Homespun" and in regard to spinning, weaving, and other aspects of Other Tales textile making. This exchange of ideas led to a great Consider, for example, the piece of cloth shown in many improvements and innovations in all the various figure 1. This piece of hand-loomed, plaid linen is aspects of textile making over time. Some of the most from the Age of Homespun-a period of American important of these developments are explained in the history lasting from colonial times up until the Civil next section of this article. Bull mummy-wrapping (from Egypt) War. During the Age of Homespun many of the necessi ties of life-including textiles-were made in the Textiles From Scratch: Fiber to Cloth home. This was especially true in remote rural areas, Traditionally the making of a piece of cloth involved .7l",;;;,;i1_ where practically every farm had its own plot of flax first the selection of an appropriate natural fiber. (For i.liIi!i,~;':;\';_-- a discussion of natural fibers, see the article on page (as well as its own flock of sheep) and there was a m1i'<!Si~ 4.) The fiber was then harvested and made ready for 1\ wool wheel and a flax wheel in every kitchen. -iW:Mii\ii\_ spinning into thread or yarn. After spinning, the yarn en@! The making of cloth for clothing and bedding de manded an enormous amount of time and energy was usually either knitted or woven into cloth.