Love's Labors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AS YOU LIKE IT: Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey 2019 AS YOU LIKE IT: Know-the-Show Guide As You Like It By William Shakespeare Directed by Paul Mullins Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of Artwork by Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey 2019 AS YOU LIKE IT: Know-the-Show Guide In this Guide – The Life of William Shakespeare ............................................................................................... 2 – As You Like It: An Introduction .................................................................................................. 3 – As You Like It: A Short Synopsis ................................................................................................. 3 – Who’s Who in the Play ............................................................................................................. 5 – Sources and History .................................................................................................................. 6 – Commentary & Criticism ........................................................................................................ 10 – Theatre in Shakespeare’s Day .................................................................................................. 11 – In this Production ................................................................................................................... 12 – Explore Online ...................................................................................................................... -

As You Like It

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S AS YOU LIKE IT By JEANNE M. McGLINN, Ph.D., AND JAMES E. McGLINN, Ed.D. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of William Shakespeare’s As You Like It 2 INTRODUCTION Shakespeare seems to be everywhere these days. Romeo and Juliet and Midsummer Night's Dream, starring contemporary movie stars, have been box office hits. The film Shakespeare in Love, depicting how the playwright's experiences inspired him to write Romeo and Juliet, won multiple Oscars at the 1999 Academy Awards. These popular films have made the plays more accessible to students by exposing them to Elizabethan language and the action that brings the words to life. So teachers can expect a certain amount of positive interest among students when they begin to read a Shakespearean play. As You Like It, although not well known by students, will certainly delight and build on students' positive expectations. As You Like It, like Twelfth Night and A Midsummer Night's Dream, is one of Shakespeare's "marriage" comedies in which love's complications end in recognition of the true identity of the lovers and celebration in marriage. This is a pattern still followed in today's romantic comedies. This play can lead to discussions of the nature of true love versus romantic love. Other themes, which spin off from the duality between the real and unreal, include appearance versus reality, nature ver- sus fortune, and court life of sophisticated manners contrasted with the natural life. -

A Reversal of Gender Role in Shakespeare's Play As You Like It

Available online at https://tjmr.org Transatlantic Journal of Multidisciplinary Research ISSN: 2672-5371 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3937843 Volume 2 │ Issue 1&2 │ 2020 A REVERSAL OF GENDER ROLE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAY AS YOU LIKE IT Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary, Assistant Professor, Tribhuwan University M. M. Campus, Nepalgunj (Nepal) Abstract This research paper has been conducted to examine Shakespeare‟s comedy As You Like It from the perspective of gender study. The voice against the strict codes, conducts and stereotypical role that are imposed on women in a patriarchal society can be seen in the play. For the analysis of the text the ideas of feminism have been used as the methodological tool to interpret it. In the play, Rosalind disguised as Ganymede, Phoebe falls hopelessly in love with Ganymede. Orlando fails to show up for his tutorial with Ganymede. Rosalind, reacting to her infatuation with Orlando, is distraught until Oliver appears. Oliver describes how Orlando stumbled upon him in the forest and saved him from being devoured by a hungry lioness. Oliver and Celia, still disguised as the shepherdess Aliena, fall instantly in love and agree to marry. The conclusion of this paper is that masculinity and feminity are not the opposites but they are interrelated. As a qualitative research, this researcher has adopted the play as a primary text and it is analyzed by using gender theory and feminist perspective as a tool to interpret it. Keywords: Gender, Feminity, Masculinity, Disguise, Role Reversal 1. Introduction This research paper is focused on the issue of gender role in Shakespeare's play, As You Like It. -

As You Like It Teacher Sample

CONTENTS Introduction to Shakespeare .........................4 Introduction to As You Like It .......................6 Character Log ..............................................8 Act I .............................................................10 Act II: Scenes 1-4 ........................................14 Act II: Scenes 5-7 ........................................18 Act III: Scenes 1-3 .......................................22 Act III: Scenes 4-6 .......................................26 Act IV ..........................................................30 Act V ...........................................................34 Epilogue .......................................................38 Review Questions ........................................40 Exams Midterm Exam .............................................44 Midterm Exam Answer Key .........................47 Final Exam ...................................................50 Final Exam Answer Key ..............................55 “... much easier in Shakespeare’s time wasn’t it? Always the same girl dressed up as a man, and even that borrowed from Boccaccio or Dante or somebody. I’m sure if I’d been a Shakespeare hero, the very minute I saw a slim-legged young page-boy I’d have said, ‘Ods-bodikins, there’s that girl again!’” Lady Swaffham in Whose Body by Dorothy Sayers 3 ACT ONE Vocabulary: 1. he keeps me rustically at home _____________________________________________________roughly; crudely 2. Marry, sir, be better employed ______________________________________________________a -

2011 As You Like It

AS YOU LIKE IT Study Guide - 2011 Season Production E DIRECT AT SPEAK MACBETH THAISAGROW PROSPERO TOUCHSTONE JULIET CRE VIEW TEACH SEE CREATE HAMLET DISCUSS CLEOPATRA SEE LISTEN LAUGHROSALIND PLAY DIRECT SHYLOCKCRE LEARN CAESAR A AT ACT TEACH E OTHELLO OPHELI A Message from the Director are transformed by encountering what is “down the rabbit hole.” stark contrast to Hamlet, As IN You Like It is a play about The forest in Shakespeare’s plays is the metamorphosis of the self. always a place of transformation, a A young woman, Rosalind, is able freeing of the self from rigid societal to discover what love truly is by and parental bonds in order to pretending to be someone else, the find an authentic self. With that boy Ganymede. Through playing in mind, we have made our forest she becomes more and more into a whimsical playground where expansive, bolder and more fully objects, clothes, sound, light and herself. color are literally transformed from what they are in the court. Through Inspiration for the physical imaginative play, the characters production of As You Like It came transform themselves. from stories like The Chronicles of Narnia, Through the Looking Glass, Thank you for celebrating the and Coraline. A door is opened into human spirit with us! another world and the characters 2 Contents Shakespeare’s Life and Times ..................................................4 What Did Shakespeare Look Like? ...........................................4 Shakespeare Portrait Gallery ....................................................5 The -

Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch An Intimate and Intermedial Form: Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J. This is a preliminary version of a book chapter published in Shakespeare Survey 69: Shakespeare and Rome, Cambridge University Press, pp. 347-360, ISBN 9781107159068 Details of the book are available on the publisher’s website: https://www.cambridge.org/core/what-we-publish/collections/shakespea... The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 An intimate and intermedial form: early television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 In the twenty-seven months between February 1937 and April 1939 the fledgling BBC television service from Alexandra Palace broadcast more than twenty Shakespeare adaptations.1 The majority of these productions were short programmes featuring ‘scenes from…’ the plays, although there were also substantial adaptations of Othello (1937), Julius Caesar (1938), Twelfth Night and The Tempest (both 1939) as well as a presentation of David Garrick’s 1754 version of The Taming of the Shrew, Katharine and Petruchio (1939). There were other Shakespeare-related programmes as well, and the playwright himself appeared in three distinct historical dramas. In large part because no recordings exist of these transmissions (or of any British television Shakespeare before 1955), these ‘lost’ adaptations have received little scholarly attention. -

As You Like It First Folio

1 As You Like It: TEACHER AND STUDENT RESOURCE GUIDE Consistent with the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s central mission to be the leading force in producing and preserving the Table of Contents highest quality classic theatre, the Education Department challenges learners of all ages to explore the ideas, emotions Synopsis 3 and characters contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between classic theatre and our modern Who’s Who 4 perceptions. We hope that this First Folio: Teacher and Student Resource Guide will prove useful to you while preparing to Close Reading Questions 5 attend As You Like It. Into the Woods: The Forest of 6 This guide provides information and activities to help students Arden and Pastoral Tradition form a personal connection to the play before attending the production. It contains material about the playwrights, their Nature vs. Fortune 7 world and their works. Also included are approaches to explore Primogeniture 8 the plays and productions in the classroom before and after the performance. Shakespeare’s Language 9 The First Folio guide is designed as a resource both for teachers and students. All activities meet the “Vocabulary Classroom Activities 13 Acquisition and Use” and “Knowledge of Language” Theatre Etiquette 15 requirements for the grades 8-12 Common Core English Language Arts Standards. We encourage you to photocopy Resource List 16 these articles and activities and use them as supplemental material to the text. Enjoy the show! Founding Sponsors The First Folio Teacher and Student Resource Guide for Miles Gilburne and Nina Zolt the 2014-2015 Season was developed by the Shakespeare Theatre Company Education Department: Leadership Support Director of Education Samantha K. -

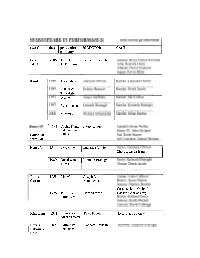

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

As You Like It by William Shakespeare

As You Like It by William Shakespeare Know-the-Show Audience Guide compiled and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey design and additional research by Meredith Keffer Cover art by Scott McKowen. art by Cover The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey As You Like It: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – The Life of William Shakespeare.......................................................2 – Shakespeare’s London......................................................................3 – As You Like It: An Introduction.........................................................4 – As You Like It: A Short Synopsis........................................................5 – Who’s Who in the Play.....................................................................8 – Is This English? - Exploring Shakespeare’s Language.........................9 – Explore Online: Links....................................................................11 – Sources and History of the Play......................................................12 – Commentary and Criticism............................................................14 – Terms from As You Like It...............................................................15 – Sources and Further Reading.........................................................16 1 The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey As You Like It: Know-the-Show Guide It is believed that Shakespeare left Stratford-on-Avon and went The Life to London around 1588. By 1592, he was a successful actor and playwright. He wrote -

The Place of a Cousin in As You Like It

The Place of a Cousin in As You Like It J ULIE CRAWFORD OR A NUMBER OF SUMMERS I have taught in an NEH-funded program for Fhigh school teachers at the Theatre for a New Audience in New York City. For two weeks, the participants spend their days studying and performing Shakespeare’s plays with academics and theater professionals.1 Among many other subjects, we frequently discuss and provide a critical language for the homoeroticism that is so prominent in plays ranging from Romeo and Juliet to The Winter’s Tale. On the whole, the participants are very interested in this topic, if frequently apprehensive about how they might teach it in highly mon- itored public schools to sexually attuned young people who can barely get over finding out that “to die” is a sexual pun. Yet amid such discussions, one thing has always remained remarkably consistent: the participants’ investment in the genre of comedy as a template for the ultimate vindication of heterosexuality. Comedies end in marriage, they insist, and thus the homoeroticism we see between Rosalind and Celia in As You Like It, for example, or between Sebas- tian and Antonio in Twelfth Night, is temporary, or, to use Valerie Traub’s still influential term, “(in)significant”—a minority concern not only resolved in the plays’ concluding marriages, but also easily ignored in class discussions neces- sarily devoted to the big issues in Shakespeare.2 1 http://www.tfana.org/education/neh-summer-institute-school-teachers. 2 Valerie Traub first used the term in “The (In)significance of ‘Lesbian’ Desire in Early Modern England,” in Erotic Politics: Desire on the Renaissance Stage, ed. -

As-You-Like-It-Guide.Pdf

Based on As You Like It by William Shakespeare and Love In A Forest by Charles Johnson with additional text fromRosalynde by Thomas Lodge Adapted and Directed by Cassie Greer July 12 - 29, 2018 The Vault Theater STUDY GUIDE CONTENTS Introduction CAST History: Origins & Influences Rosalind ........................................................................ Amber Bogdewiecz Our Production Celia ................................................................................ Arianne Jacques‡ Themes Orlando ............................................................................. Israel Bloodgood Jaques ................................................................................... Andrew Beck‡ Language & Shakespeare Charles/Lord/Phebe ............................................................... Signe Larsen† Discussion Questions & Writing Activities Marshall/Adam/Silvius ...................................................... Roxanne Stathos Sources & Le Beau/Amiens ......................................................................... Jared Mack Further Reading Duke Frederick/Duke Senior ................................................. TS McCormick BAG&BAGGAGE STAFF CREW/PRODUCTION TEAM Scott Palmer Founding Artistic Director Adaptor and Director .............................................................. Cassie Greer Costume Designer ................................................................ Melissa Heller Beth Lewis Managing Director Scenic Designer & Lighting Designer ................................ Jim Ricks-White -

As You Like It Teacher Pack 2013

AS YO U LIKE IT BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE E D U C A T I O N A C T I V I T I E S P A C K ABOUT THIS PACK This pack supports the RSC’s 2013 production of As You Like It, directed by Maria Aberg, which opened on April 12th at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and runs until September 28th. This pack has been written for use with Key Stage 3 to 5 Drama, Theatre Studies and English students, but many of the activities can be adapted for younger age groups. The activities aim to help students explore some important features of the text and production, using the RSC’s rehearsal processes. The pack contains: Background information about the original staging of the play Introductory information about the creation of the current production Practical activities inspired by the current production ABOUT OUR EDUCATION WORK We want children and young people to enjoy the challenge of Shakespeare and achieve more as a result of connecting with his work. Central to our education work is our manifesto for Shakespeare in schools, Stand up for Shakespeare. We know that children and young people can experience Shakespeare in ways that excite, engage and inspire them. We believe that young people get the most out of Shakespeare when they: ■ Do Shakespeare on their feet - exploring the plays actively as actors do ■ See it Live - participate as members of a live audience ■ Start it Earlier - work on the plays from a younger age We also believe in the power of ensemble - a way of working together in both the rehearsal room and across the company enabling everyone’s ideas and voices to be heard.