Institute of Jerusalem Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Palestinian Authority (PA) Fight Against COVID-19 (Updated to March 31, 2020)

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו רור The Palestinian Authority (PA) Fight Against COVID-19 (Updated to March 31, 2020) March 31, 2020 Data of the Spread of COVID-19 in the PA Territories On March 31, 2020, the number of Palestinian COVID-19 cases rose to 117, 107 in Judea and Samaria and 10 in the Gaza Strip.1 The cases most recently detected in the PA were a Palestinian worker who returned from Israel and seven Palestinians in the village of Qatanna, northwest of Jerusalem. The village and the Bethlehem area are focal points for the spread of the disease: there are 39 COVID-19 cases in Qatanna and 46 in the Bethlehem area. So far 18 Palestinians have recovered and one has died (Wafa, March 31, 2020; Palestinian TV, QudsN Facebook page, March 30, 2020). Dr. Ghassan Nimr, spokesman for the Palestinian ministry of the interior, briefed journalists on March 30 and 31 about the geographic distribution of COVID-19 in the PA territories. -

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

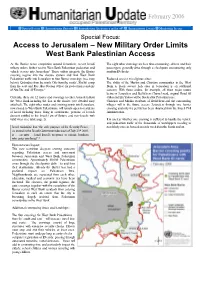

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

NABI SAMWIL Saint Andrew’S Evangelical Church - (Protestant Hall) Ramallah - West Bank - Palestine 2018

About Al-Haq Al-Haq is an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organisation based in Ramallah, West Bank. Established in 1979 to protect and promote human rights and the rule of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the organisation has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council. Al-Haq documents violations of the individual and collective rights of Palestinians in the OPT, regardless of the identity of the perpetrator, and seeks to end such breaches by way of advocacy before national and international mechanisms and by holding the violators accountable. The organisation conducts research; prepares reports, studies and interventions on the breaches of international human rights and humanitarian law in the OPT; and undertakes advocacy before local, regional and international bodies. Al-Haq also cooperates with Palestinian civil society organisations and governmental institutions in order to ensure that international human rights standards are reflected in Palestinian law and policies. The organisation has a specialised international law library for the use of its staff and the local community. Al-Haq is also committed to facilitating the transfer and exchange of knowledge and experience in international humanitarian and human rights law on the local, regional and international levels through its Al-Haq Center for Applied International Law. The Center conducts training courses, workshops, seminars and conferences on international humanitarian law and human rights for students, lawyers, journalists and NGO staff. The Center also hosts regional and international researchers to conduct field research and analysis of aspects of human rights and IHL as they apply in the OPT. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

Palestinian Cultural and Religious Heritage in Jerusalem

PALESTINIAN CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS HERITAGE IN JERUSALEM Painting by Abed Rahman Abu Arafeh, Damascus Gate (1997) INTRODUCTION October 2020 The Old City of Jerusalem is distinguished from any other historic city for its universal value. It is home to the most sacred religious Contents: shrines in the world, including Al-Aqsa Mosque/Al-Haram Al-Shar- if, Al-Buraq Wall also known as the Western Wall, and the Church Introduction.............................................................. 1 of the Holy Sepulcher. Within its walls, one can find numerous 1. Historical Background........................................... 2 mosques, churches, convents, zawayas1 and mausoleums sacred to 2. Palestinian Culture and Heritage in Jerusalem ..... 3 many believers worldwide. 2.1 Tangible Heritage (Landmarks and Artefacts)......3 2.2 Intangible Heritage (Palestinian Culture and Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (at the request of the Identity) ............................................................. 6 Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan) since 1981, the Old City of Jerusalem 3. Violations Against Religious and Cultural and its Walls have a unique and valuable historic, religious and Heritage in Jerusalem .......................................... 8 cultural heritage and identity, that was skillfully builtover centuries, and demonstrates the diverse urban and architectural styles 3.1 Israeli Attempts to Erase Palestinian Culture developed over centuries. UNESCO’s 1982 listing of the Old City as from Jerusalem ................................................. -

Relocation Plan Final

21 Land Defense Coalition Stop the Wall Campaign Between August 25 and September 9 2014, the Israeli lorem ipsum dolor civil administration published Israel is planning to forcibly relocate some 27,000 plans to build a new settlement sit amet. Bedouin communities living in Area C in the occupied “Ramat Nu’eimeh” in West Bank to three 'relocation' townships in order to Inweimeh near Jericho in order to house about 12,500 prepare Area C (over 60% of the West Bank) for final Palestinian Bedouin from the annexation. Jahalin, Kaabneh and Rashaida tribes that are to be expelled from their homes and lands in the Jordan Valley and the E1 page 3 area east of Jerusalem. The area slated for the township is owned by Palestinian villages Stop and comprises 1,460 dunams. Two other 'relocation' townships are to be built: one in the area of Abu Dis, close to Israel's the Jerusalem rubbish dump where already some x Bedouin have been expelled to in 1997 and 2012, the other one in the northern Jordan Valley. 'Relocation' Expulsion starts with 20 communities, comprising some 2,300 people, to be uprooted plan from the area slated for the expansion of the illegal Ma'ale Adummim settlement (E1 area) and then forcibly transferred to the site next to the Abu Dis garbage dump. Asked if Israeli authorities plan to put the communities on trucks to 'relocate' them (as happened in 1997) Yuval Turgeman, the director of Bedouin affairs of the Civil Administration answers: “We won’t put them on trucks. But we’ll take immediate action to demolish their residences and agricultural buildings, because there is an alternative here.” 12 April 2015 "It's clear now that the plan is much bigger. -

English/Deportation/Statistics

International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion Proceedings On Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Palestine Written Statement (30 January 2004) And Oral Pleading (23 February 2004) Preface 1. In October of 2003, increasing concern about the construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, in departure from the Armistice Line of 1949 (the Green Line) and deep into Palestinian territory, brought the issue to the forefront of attention and debate at the United Nations. The Wall, as it has been built by the occupying Power, has been rapidly expanding as a regime composed of a complex physical structure as well as practical, administrative and other measures, involving, inter alia, the confiscation of land, the destruction of property and countless other violations of international law and the human rights of the civilian population. Israel’s continued and aggressive construction of the Wall prompted Palestine, the Arab Group, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to convey letters to the President of the United Nations Security Council in October of 2003, requesting an urgent meeting of the Council to consider the grave violations and breaches of international law being committed by Israel. 2. The Security Council convened to deliberate the matter on 14 October 2003. A draft resolution was presented to the Council, which would have simply reaffirmed, inter alia, the principle of the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force and would have decided that the “construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a wall in the Occupied Territories departing from the armistice line of 1949 is illegal under relevant provisions of international law and must be ceased and reversed”. -

Download the PDF File

This study focuses on the role of the Mirage in the Sands: Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, the Ottoman Special Organization (SO), in the Sinai-Palestine The Ottoman Special front during the First World War. The Organization on the SO was defined by its use of various tactics of unconventional warfare, namely Sinai-Palestine Front intelligence-gathering, espionage, guerilla Polat Safi warfare, and propaganda. Along the Sinai- Palestine front, the operational goal to which these tactics were put to use was to bring about an uprising in British-occupied Egypt.1 The SO hoped to secure the support of the tribal and Bedouin populations of Sinai-Palestine front and the people of Egypt and encourage them to rise up against the British rule.2 The SO’s involvement on the Sinai- Palestine front was part of a broader effort developed between Germany and the Ottoman State for the purposes of encircling Egypt. An examination of the SO’s work in Palestine will illuminate the nature of the peripheral strategy the Germans and Ottomans employed outside of Europe during World War I and how it was applied in practice. As part of this broader strategy, in Palestine the SO engaged in a volunteer recruitment campaign, worked to foment rebellion behind enemy lines, engaged in guerilla warfare, and carried out intelligence duties. By examining the nature and contours of the SO’s operations there, this study aims to provide both new insights into the regional aspects of a crucial organization and also valuable information which will offer a firmer ground for future comparative studies on the different operational bases of the SO. -

The Judaization of Jerusalem/Al-Quds

Published by Americans for The Link Middle East Understanding, Inc. Volume 51, Issue 4 Link Archives: www.ameu.org September-October 2018 The Judaization of Jerusalem/Al-Quds by Basem L. Ra'ad About This Issue: Basem Ra’ad is a professor emeritus at Al-Quds University in Jerusalem. This is his second feature article for The Link; his first, “Who Are The Ca- naanites’? Why Ask?,” appeared in our December, 2011 issue. John F. Mahoney, Executive Director The Link Page 2 The Judaization of Jerusalem / Al-Quds Board of Directors by Basem L. Ra'ad Jane Adas, President Elizabeth D. Barlow Edward Dillon Henrietta Goelet John Goelet At last year’s Toronto Palestinian Film Festival, I attended a session Richard Hobson, Treasurer entitled “Jerusalem, We Are Here,” described as an interactive tour of 1948 Anne R. Joyce, Vice President West Jerusalem. It was designed by a Canadian-Israeli academic specifically Janet McMahon as a virtual excursion into the Katamon and Baqʿa neighborhoods, inhabited John F. Mahoney, Ex. Director by Christian and Muslim Palestinian families before the Nakba — in Darrel D.Meyers English, the Catastrophe. Brian Mulligan Daniel Norton Little did I anticipate the painful memories this session would bring. Thomas Suárez The tour starts in Katamon at an intersec- James M. Wall tion that led up to the Semiramis Hotel. The hotel was blown up by the Haganah President-Emeritus on the night of 5-6 January 1948, killing 25 Robert L. Norberg civilians, and was followed by other at- National Council tacks intended to vacate non-Jewish citi- Kathleen Christison zens from the western part of the city.