Why Are Business Corporation Laws Largely Enabling Elvin R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AT&T Business Trade-In Program in Premier

AT&T Business Trade-In program in Premier Company Administrator Quick Guide July 2019 1 © 2019 AT&T Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. AT&T, Globe logo, Mobilizing Your World and DIRECTV are registered trademarks and service marks of AT&T Intellectual Property and/or AT&T affiliated companies. All other marks are the property of their respective owners. AT&T Business Trade-In overview © 2019 AT&T Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. AT&T, Globe logo, Mobilizing Your World and DIRECTV 2 are registered trademarks and service marks of AT&T Intellectual Property and/or AT&T affiliated companies. All other marks are the property of their respective owners. AT&T Business Trade-In benefits Capitalize on the mobile lifecycle The AT&T Business Trade-In program helps company administrators get the newest devices faster - and with less out- of-pocket costs. The program enables you to trade in your old wireless devices from any carrier and receive credit for their value. The credit is applied directly to your AT&T wireless account, usually within 2 billing cycles, helping to offset the costs of future investments. Value Security Environmental Stewardship Device value is applied as credits Industry-leading data Devices are responsibly recycled, to your wireless bill, offsetting protection with certified in compliance with environmental future device investments. sanitization process. certifications of R2, ISO 14001 & OHSAS 1800. Images provided in this presentation are for illustrative purposes only. 3 © 2019 AT&T Intellectual Property. All rights reserved. AT&T, Globe logo, Mobilizing Your World and DIRECTV are registered trademarks and service marks of AT&T Intellectual Property and/or AT&T affiliated companies. -

College of Business and Economics Supply Chain Management

COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT BACHELOR OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT What is Supply Chain Management? Much more than logistics, Supply Chain Management (SCM) integrates supply and demand management within and across companies. It is one of the most critical issues in global business today, and offers outstanding career opportunities for suitably qualified graduates. Supply chain spending is growing faster than the overall economy, and in 2006 over $1.3 trillion was spent on SCM activities, which was more than 9.5% of the U.S. GDP. What are the typical job opportunities in SCM? There is plenty of good news for new graduates in the fascinating and diverse field of SCM. Opportunities abound in manufacturing and production companies, retailers and distributors, consulting firms, service firms, government agencies, transportation companies, third party logistics providers, and universities and educational institutions. Famous firms such as Nestlé, WalMart, Disney, Best Buy, Caterpillar, Boeing, Microsoft, Hewlett- Packard, and Nike, are just a few of the names of firms whose SCM expertise is legendary. What is the salary outlook in SCM? Excellent employment prospects, a fast-paced, fulfilling work environment, and the opportunity for career growth all sound great, but you’re still thinking “show me the money!” Starting SCM salaries for 2007 college graduates with a SCM major average $45,771 according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers. And that’s just the beginning! As your experience and responsibilities grow, you can expect to earn an average of $89,300 as a Supply Chain Manager, according to the 2007 Mercer Benchmark Database for Logistics and Supply Chain Positions. -

1.1 International Trade 1.2 Global Business Basics 1.3

GLOBAL BUSINESS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE “How can our company sell electric motors in Eastern Europe?” “What are the biggest markets for soft drinks in Asia?” “What trade barriers might be encountered when doing business in Latin America?” Trade Specialists at Export 1.1 INTERNATIONAL TRADE Assistance Centers of the U.S. Department of Commerce are ready to answer these, and other, international trade questions. With offices in more than 80 cities around the U.S., Trade Specialists are able to 1.2 GLOBAL BUSINESS • research potential foreign markets for a product or service • help locate customers in other BASICS countries • assist with developing an interna- tional marketing plan Additional exporting and interna- tional trade information is available 1.3 ECONOMICS OF GLOBAL from the U.S. Department of Commerce at www.ita.doc.gov and www.usatrade.gov BUSINESS THINK CRITICALLY 1. Why are Export Assistance Centers important to business and the economy? 2. What skills would be necessary to work as a trade specialist in an Export Assistance Center? The Chapter 1 video for this module introduces the concepts in this chapter. A Global Business Plan PROJECT OBJECTIVES I Become aware of the geographic, economic, cultural, and political factors that influence international business activities I Develop an understanding of methods used for measuring international trade activities I Explain the factors that influence the level of economic development in a country GETTING STARTED Read through the Project Process below. Make a list of materials that you will need. Decide how you will get the needed materials or information. -

Ownership and Control of Private Firms

WJEC BUSINESS STUDIES A LEVEL 2008 Spec. Issue 2 2012 Page 1 RESOURCES. Ownership and Control of Private Firms. Introduction Sole traders are the most popular of business Business managers as a businesses steadily legal forms, owned and often run by a single in- grows in size, are in the main able to cope, dividual they are found on every street corner learn and develop new skills. Change is grad- in the country. A quick examination of a busi- ual, there are few major shocks. Unfortu- ness directory such as yellow pages, will show nately business growth is unlikely to be a that there are thousands in every town or city. steady process, with regular growth of say There are both advantages and disadvantages 5% a year. Instead business growth often oc- to operating as a sole trader, and these are: curs as rapid bursts, followed by a period of steady growth, then followed again by a rapid Advantages. burst in growth.. Easy to set up – it is just a matter of in- The change in legal form of business often forming the Inland Revenue that an individ- mirrors this growth pattern. The move from ual is self employed and registering for sole trader to partnership involves injections class 2 national insurance contributions of further capital, move into new markets or within three months of starting in business. market niches. The switch from partnership Low cost – no legal formalities mean there to private limited company expands the num- is little administrative costs to setting up ber of manager / owners, moves and rear- as a sole trader. -

Partnership Agreement Example

Partnership Agreement Example THIS PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT is made this __________ day of ___________, 20__, by and between the following individuals: Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ Address: __________________________ ___________________________ City/State/ZIP:______________________ 1. Nature of Business. The partners listed above hereby agree that they shall be considered partners in business for the following purpose: ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Name. The partnership shall be conducted under the name of ________________ and shall maintain offices at [STREET ADDRESS], [CITY, STATE, ZIP]. 3. Day-To-Day Operation. The partners shall provide their full-time services and best efforts on behalf of the partnership. No partner shall receive a salary for services rendered to the partnership. Each partner shall have equal rights to manage and control the partnership and its business. Should there be differences between the partners concerning ordinary business matters, a decision shall be made by unanimous vote. It is understood that the partners may elect one of the partners to conduct the day-to-day business of the partnership; however, no partner shall be able to bind the partnership by act or contract to any liability exceeding $_________ without the prior written consent of each partner. 4. Capital Contribution. The capital contribution of -

The Institutions of Corporate Governance

ISSN 1045-6333 HARVARD JOHN M. OLIN CENTER FOR LAW, ECONOMICS, AND BUSINESS THE INSTITUTIONS OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Mark J. Roe Discussion Paper No. 488 08/2004 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=###### This paper is also a discussion paper of the John M. Olin Center's Program on Corporate Governance JEL K4, H73, G34, G28 The Institutions of Corporate Governance Mark J. Roe* Abstract In this review piece, I outline the institutions of corporate governance decision- making in the large public firm in the wealthy West. By corporate governance, I mean the relationships at the top of the firm—the board of directors, the senior managers, and the stockholders. By institutions I mean those repeated mechanisms that allocate authority among the three and that affect, modulate, and control the decisions made at the top of the firm. Core corporate governance institutions respond to two distinct problems, one of vertical governance (between distant shareholders and managers) and another of horizontal governance (between a close, controlling shareholder and distant shareholders). Some institutions deal well with vertical corporate governance but do less well with horizontal governance. The institutions interact as complements and substitutes, and many can be seen as developing out of a “primitive” of contract law. In Part I, I sort out the central problems of corporate governance. In Part II, I catalog the basic institutions of corporate governance, from markets to organization to contract. -

Business License Renewal Application Packet

2021 Occupation Tax Renewal Notice This notice serves as an official billing notification to explain how to determine your business occupation tax amount. All Occupation Tax renewals are due by March 15, 2021 for the 2021 calendar year. Occupation Tax is determined using a method based on gross receipts. The standard exemption for all businesses is $100,000. Other deductions as described in the City of Roswell Code of Ordinances, Section 10.3.1 may also apply. Additionally, all businesses with 100 or more full-time employees will be assessed a fee of $12 per employee. Gross receipts are the total amount a business received from all sources during its annual accounting period, without subtracting any costs or expenses. Business types are categorized by NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) codes. This code is assigned a profitability index which corresponds with a specific tax rate. The tax rate applied to gross receipts will determine the tax assessment. New for 2021 Businesses will no longer provide an estimate of gross receipts for the upcoming year as the basis for calculating occupation tax. Beginning in 2021, occupation tax will be calculated based upon the prior year’s actual gross receipts. Tax rates for each NAICS code have been updated based upon the latest available profitability information from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This may result in a change to your business’s tax class and rate for 2021. 1 2021 Fee Structure Commercial Business The tax due will equal gross receipts, less a $100,000 exemption and any other allowable deductions, multiplied by the tax rate. -

What Is Corporate Law?

ISSN 1936-5349 (print) ISSN 1936-5357 (online) HARVARD JOHN M. OLIN CENTER FOR LAW, ECONOMICS, AND BUSINESS THE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF CORPORATE LAW: WHAT IS CORPORATE LAW? John Armour, Henry Hansmann, Reinier Kraakman Discussion Paper No. 643 7/2009 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract_id=####### This paper is also a discussion paper of the John M. Olin Center’s Program on Corporate Governance. The Essential Elements of Corporate Law What is Corporate Law? John Armour University of Oxford - Faculty of Law; Oxford-Man Institute of Quantitative Finance; European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) Henry Hansmann Yale Law School; European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) Reinier Kraakman Harvard Law School; John M. Olin Center for Law; European Corporate Governance Institute Abstract: This article is the first chapter of the second edition of The Anatomy of Corporate Law: A Comparative and Functional Approach, by Reinier Kraakman, John Armour, Paul Davies, Luca Enriques, Henry Hansmann, Gerard Hertig, Klaus Hopt, Hideki Kanda and Edward Rock (Oxford University Press, 2009). The book as a whole provides a functional analysis of corporate (or company) law in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. Its organization reflects the structure of corporate law across all jurisdictions, while individual chapters explore the diversity of jurisdictional approaches to the common problems of corporate law. In its second edition, the book has been significantly revised and expanded. -

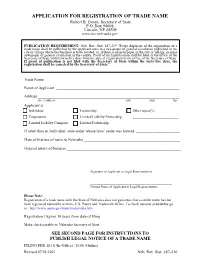

APPLICATION for REGISTRATION of TRADE NAME Robert B

APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE NAME Robert B. Evnen, Secretary of State P.O. Box 94608, Lincoln, NE 68509 www.sos.nebraska.gov PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT: Neb. Rev. Stat. §87-219 "Every duplicate of the registration of a trade name shall be published by the applicant once in a newspaper of general circulation published in the city or village where the business is to be located, or, if there is no newspaper in the city or village, in some newspaper of general circulation in the county. Proof of such publication shall be filed in the office of the Secretary of State within forty-five days from the date of registration in the office of the Secretary of State. If proof of publication is not filed with the Secretary of State within the forty-five days, the registration shall be canceled by the Secretary of State." Trade Name _____________________________________________________________________ Name of Applicant ____________________________________________________________________ Address ________________________________________________________________________ street address city state zip Applicant is Individual Partnership Other (specify) Corporation Limited Liability Partnership ____________________________ Limited Liability Company Limited Partnership If other than an Individual, state under whose laws’ entity was formed: ___________________________ Date of first use of name in Nebraska _________________________________________________ General nature of business __________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________ -

General Partnership

BUSINESS ENTITIES VIDEO SERIES, Script Three GENERAL PARTNERSHIP A general partnership is a business owned by two or more people (even a husband and wife), who carry on the business as a partnership. Partnerships have specific attributes, which are defined by Kansas Statutes. All partners share equally in the right and responsibility to manage the business. Each partner is responsible for all debts and obligations of the business. The distribution of profits and losses, allocation of management responsibilities and other issues affecting the partnership are usually defined in a written partnership agreement. General partnerships may file different statements with the Office of the Secretary of State. The filings are optional and not mandatory. The filing fee for Partnership Statements is $35. General partnerships have certain advantages. A general partnership is easy to organize and has few initial costs. A general partnership draws financial resources and business abilities from all partners. It has quasi-entity status in that it may own assets, contract in the partnership name, may sue and be sued in the partnership name and may file separate bankruptcy. Liability is shared by all partners. Partners may take business losses as a personal income tax deduction. The partnership may register a trademark or a service mark to help prevent confusion resulting from deceptively similar business names. General partnerships have certain disadvantages. Each partner is personally liable for all the obligations of the business, not just his or her share. Thus, if a company truck is involved in an accident, each partner's personal assets may be attached by the court to help compensate the injured party. -

Start-Up a Cooperative

Start.COOP A STEP-BY-STEP TOOL TO START-UP A COOPERATIVE Start.COOP by International Labour Organization (ILO) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Unported License. Start.COOP Start.COOP has been developed as a low-cost, easy to use training tool for those interested in starting and launching a cooperative in a participatory and efficient manner. It draws on technical content from existing materials in different ILO cooperative training tools and peer-to-peer, activity based learning methodology from the ILO’s Community-Based Enterprise Development (C-BED) pro- gramme. The Start.COOP training tool has been divided into four modules that correspond to each phase of the cooperative formation process to give you time to reflect on the importance of what you are doing at a given time and to see how it fits into the big picture. The focus of the Start.COOP modules is on the decisions to be made at each step with a view to increasing chances of success. At the end of the training you will be able to: • Identify the core members of your cooperative • Define your business idea • Research the feasibility of your business idea • Prepare your business plan • Decide on the organizational set-up of your cooperative To learn more about the ILO’s work on cooperatives visit www.ilo.org/coop or email: [email protected] To learn more about the ILO’s peer-to-peer, activity based learning methodology visit www.cb-tools.org Acknowledgements Start.COOP was developed collaboratively by the ILO Decent Work Team Bangkok and the Coopera- tives Unit of the Enterprises Department at the ILO. -

Think.COOP by International Labour Organization (ILO) Is Licensed Under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License

AN ORIENTATION ON THE COOPERATIVE BUSINESS MODEL TRAINING GUIDE Think.COOP by International Labour Organization (ILO) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Think.COOP has been developed as a low-cost, easy to use training tool for those interested in establishing or joining a cooperative. It draws on technical content from existing materials in different ILO cooperative training tools and peer-to-peer, activity based learning methodology from the ILO’s Community-Based Enterprise Development (C-BED) programme, Think.COOP provides simple information on the basics of cooperatives. At the end of the one-day orientation, participants are expected to: • Understand what a cooperative is (values and principles, differences from other forms of organizations and enterprises etc.) • Understand the specific benefits and challenges related to cooperative model compared to other types of enterprises or economic organizations; and • Be able to make an informed and conscious decision of whether a cooperative might be a suitable business option for the participant. To learn more about the ILO’s work on cooperatives visit www.ilo.org/coop or email: [email protected] To learn more about the ILO’s peer-to-peer, activity based learning methodology visit www.cb-tools.org Acknowledgements Think.COOP was developed collaboratively by the ILO Decent Work Team Bangkok and the Coopera- tives Unit of the Enterprises Department of the ILO. Text was drafted by Marian E. Boquiren. Think.COOP ILO Enterprises Department