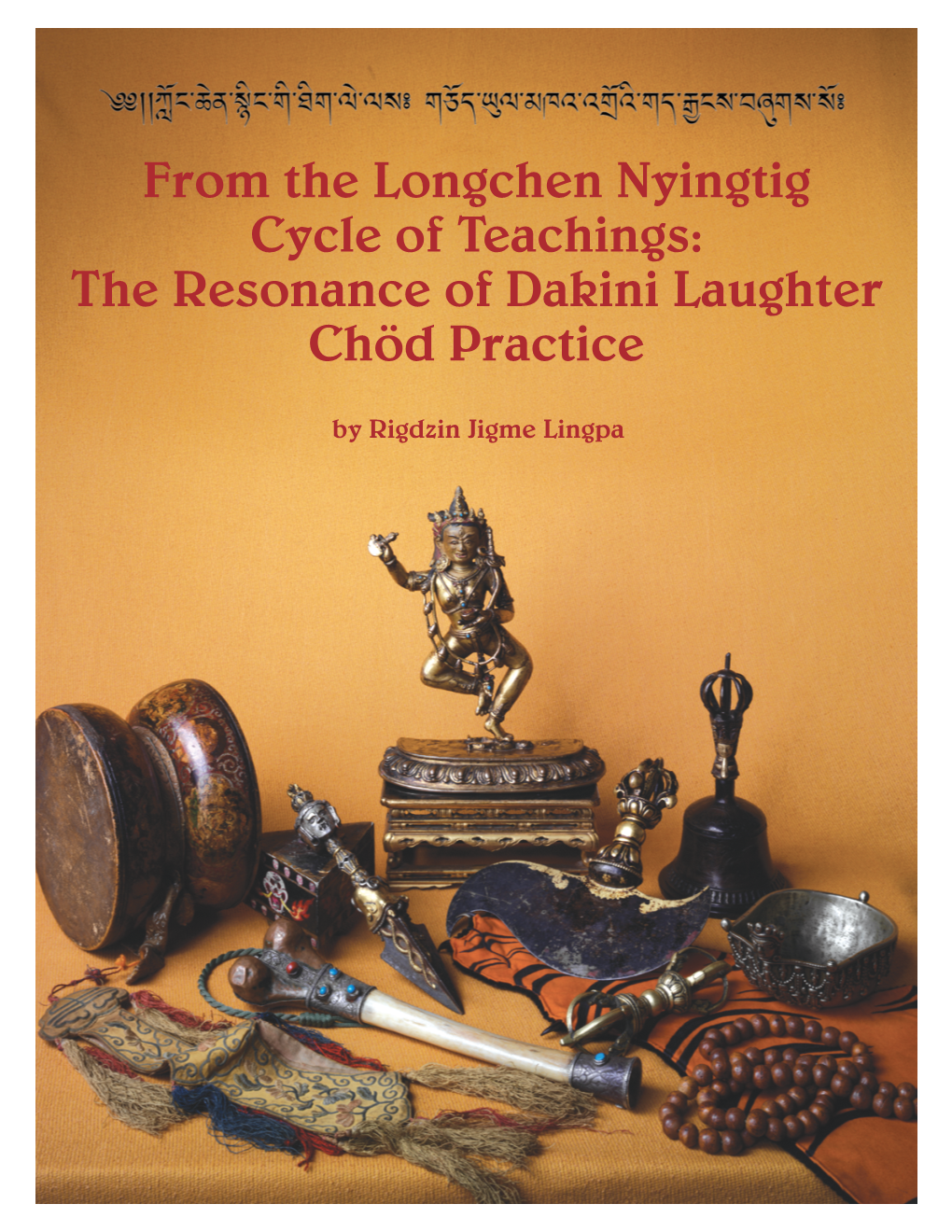

The Resonance of Dakini Laughter Chöd Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Sakya Institute for Buddhist Studies Calendar.Xlsx

SAKYA INSTITUTE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES 59 Church Street, Unit 3 Cambridge, MA 02138 sakya.net Registration is required by emaiL ([email protected]) Time Requirement Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 26th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 25th; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. January Prajnaparamita Weekend Retreat 14th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Lion Headed Dakini Simhamukha Weekend Retreat 21st; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Sitatapatra (White Umbrella) Weekend Retreat 28th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 7th, 14th, 21st, 28th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice February Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 1st, 8th, 15th, 22nd; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 4th, 11th, 18th, 25th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. -

The Dakini Project

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2014 The Dakini Project Kimberley Harris Idol University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Repository Citation Idol, Kimberley Harris, "The Dakini Project" (2014). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2094. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/5836113 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DAKINI PROJECT: TRACKING THE “BUTTERFLY EFFECT” IN DETECTIVE FICTION By Kimberley Harris Idol Bachelor of Arts in Literature Mount Saint Mary’s College 1989 Master of Science in Education Mount Saint Mary’s College 1994 Master of Arts in Literature California State University, Northridge 2005 Master of Fine Arts University -

Transfer of Buddhism Across Central Asian Networks (7Th to 13Th Centuries)

Transfer of Buddhism Across Central Asian Networks (7th to 13th Centuries) Edited by Carmen Meinert LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Acknowledgements vii List of Illustrations, Maps and Tables viii General Abbreviations xi Bibliographical Abbreviations xii Notes on Contributors xiv Introduction—Dynamics of Buddhist Transfer in Central Asia 1 Carmen Meinert Changing Political and Religious Contexts in Central Asia on a Micro-Historical Level 1 Changing Relations between Administration, Clergy and Lay People in Eastern Central Asia: A Case Study according to the Dunhuang Manuscripts Referring to the Transition from Tibetan to Local Rule in Dunhuang, 8th–11th Centuries 19 Gertraud Taenzer Textual Transfer 2 Tibetan Buddhism in Central Asia: Geopolitics and Group Dynamics 57 Sam van Schaik 3 The Transmission of Sanskrit Manuscripts from India to Tibet: The Case of a Manuscript Collection in the Possession of Atiśa Dīpaṃkaraśrījñāna (980–1054) 82 Kazuo Kano Visual Transfer 4 The Tibetan Himalayan Style: Considering the Central Asian Connection 121 Linda Lojda, Deborah Klimburg-Salter and Monica Strinu For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV vi contents 5 Origins of the Kashmiri Style in the Western Himalayas: Sculpture of the 7th–11th Centuries 147 Rob Linrothe Transfer Agents 6 Buddhism in the West Uyghur Kingdom and Beyond 191 Jens Wilkens 7 Esoteric Buddhism at the Crossroads: Religious Dynamics at Dunhuang, 9th–10th Centuries 250 Henrik H. Sørensen Bibliography 285 Index 320 For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV Chapter 2 Tibetan Buddhism in Central Asia: Geopolitics and Group Dynamics Sam van Schaik 1 Introduction1 Tibetan Buddhism has played an important role in Asian politics from the 8th century to the present day. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

The Foundation of All Good Qualities by Lama Tsongkhapa

PRACTICE The Foundation of All Good Qualities By Lama Tsongkhapa In the 11th century, Tibet was blessed by the arrival of capacities of varying practitioners — small, medium, and the Indian Buddhist master Lama Atisha. Motivated to pres- great — which organize practices and meditations on the ent an organized summary of the sutra teachings, Atisha path into gradual stages. composed a short text entitled, The Lamp of the Path. Three Lama Tsongkhapa's famous prayer, The Foundation of hundred years later, Lama Tsongkhapa expanded upon this All Good Qualities, is the most concise and stirring outline text with his opus The Great Exposition on the Stages of the available of the Lam-Rim teachings. In only fourteen stanzas, Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo). The often referred Tsongkhapa offers us a prayer that covers the entire graduated to "Lam-Rim teachings" are taken from this seminal text. path to enlightenment, short enough to recite every day, The teachings are presented in three scopes according to the profound enough to study for a lifetime. The foundation of all good qualities is the kind and venerable guru; I will not achieve enlightenment. Correct devotion to him is the root of the path. With my clear recognition of this. By clearly seeing this and applying great effort, Please bless me to practice the bodhisattva vows with great energy. Please bless me to rely upon him with great respect. Once I have pacified distractions to wrong objects Understanding that the precious freedom of this rebirth is found And correctly analyzed the meaning of reality, only once. -

Red Lion-Face Dakini Feast Gathering on the 25Th Day of Each Lunar Month

NYINGMA KATHOK BUDDHIST CENTRE PRAYER TEXT RED LION-FACE DAKINI FEAST GATHERING ON THE 25TH DAY OF EACH LUNAR MONTH PAGE 1 VERSES OF SUPPLICATION TO THE EIGHT AUSPICIOUS ARYAS When commencing any activity, by reciting these verses of auspiciousness once at the start, the activity will be accomplished smoothly and in accordance with one’s wishes. Therefore these verses should be given attention to. OM NANG SID NAM DAG RANG ZHIN LHUN DRUB PI TA SHI CHHOG CHUI ZHING NA ZHUG PA YI SANG GYE CHHO TANG GEN DUN PHAG PI TSHOG KUN LA CHHAN TSHAL DAG CHAG TA SHI SHOG Om, To the Buddhas, the Dharmas and Sanghas, The aryan assembly dwelling in the auspicious realms in the ten directions Where apparent existences are pure and spontaneously existent, I prostrate to them all and thus may there be auspiciousness for us all. DRON MI GYAL PO TSAL TEN THON DRUB GONG JAM PI GYEN PAL GE THRAG PAL DAM PA KUN LA GONG PA GYA CHHER THRAG PA CHEN King Of The Lamp, Enlightened Mind Of Stable Power Accomplishing Aims, Glorious Adornment Of Love, Glorious Sacred One Whose Virtues Are Renowned, Vastly Renowned In Giving Attention To All, PAGE 2 LHUN PO TAR PHAG TSAL THRAG PAL TANG NI SEM CHEN THAM CHE LA GONG THRAG PI PAL YID TSHIM DZED PA TSAL RAB THRAG PAL TE TSHEN TSAM THO PE TA SHI PAL PHEL WA DE WAR SHEG PA GYED LA CHHAN TSHAL LO Glorious One Renowned As Strong And Exalted Like Sumeru, Glorious One Renowned In Giving Attention To All Sentient Beings, Glorious One Renowned As Strong And Exalted Who Satisfies Beings' Minds, Merely hearing your names increases auspiciousness and success, Homage to the eight Sugatas. -

Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava Essay

Mirrors of the Heart-Mind - Eight Manifestations of Padmasam... http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/sama/Essays/AM9... Back to Exhibition Index Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava (Image) Thangka, painting Cotton support with opaque mineral pigments in waterbased (collagen) binder exterior 27.5 x 49.75 inches interior 23.5 x 34.25 inches Ca. 19th century Folk tradition Museum #: 93.011 By Ariana P. Maki 2 June, 1998 Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, Padmakara, or Tsokey Dorje, was the guru predicted by the Buddha Shakyamuni to bring the Buddhist Dharma to Tibet. In the land of Uddiyana, King Indrabhuti had undergone many trials, including the loss of his young son and a widespread famine in his kingdom. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara felt compassion for the king, and entreated the Buddha Amitabha, pictured directly above Padmasambhava, to help him. From his tongue, Amitabha emanated a light ray into the lake of Kosha, and a lotus grew, upon which sat an eight year old boy. The boy was taken into the kingdom of Uddiyana as the son of King Indrabhuti and named Padmasambhava, or Lotus Born One. Padmasambhava grew up to make realizations about the unsatisfactory nature of existence, which led to his renunciation of both kingdom and family in order to teach the Dharma to those entangled in samsara. Over the years, as he taught, other names were bestowed upon him in specific circumstances to represent his realization of a particular aspect of Buddhism. This thangka depicts Padmasambhava, in a form also called Tsokey Dorje, as a great guru and Buddha in the land of Tibet. -

AyyaYeshe How To Be A

Ayya Yeshe How to Be a Light for Yourself and Others in Challenging Times Week One: “Establishing the Basis for Dharma Practice” September 4, 2017 Hi, I'm Ayya Yeshe. I'm an Australian Buddhist nun and I've been ordained 16 years. I'm the director of Bodhicitta Foundation, a charity for people in the slums of Central India, which has been running for over a decade. I'm also the founding abbess of a monastery in Australia, which we are currently raising funds for, called Khandro Ling Hermitage. I'm mainly from the Sakya tradition but I was ordained as a fully ordained nun by Thich Nhat Hanh, the Nobel Peace Prize nominee and Vietnamese Zen master. Today I would like to talk about The Seven Points of Mind Training by Geshe Chekawa, which is mainly from the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. It's actually quite a long and involved text but it's a wonderful introduction to Mahayana Buddhism. As we go through the text, I hope that I can make some of -

Inner Mongolia

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN30730 Country: China Date: 13 October 2006 Keywords: CHN30730 – Tibetan Buddhism – Government Treatment – Inner Mongolia This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. 2. Please provide information on the Chinese government’s treatment of this group, especially in Mongolia. RESPONSE 1. Please provide some background information on this Huang Jiao group. The file indicates that the applicant is from Tongliao, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The applicant claims to practice a religion from Tibet similar to Buddhism. According to the US Department of State, most ethnic Mongolians practice Tibetan Buddhism (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report 2006 – China, 15 September, Section 1 – Attachment 1). Huang Jiao means yellow religion in Chinese. One reference to huang jiao was found amongst the sources consulted. The article published in The Drama Review in 1989 reports that huang jiao is the yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism (Liuyi, Qu et al 1989, ‘The Yi: Human Evolution Theatre’, The Drama Review, Vol 33, No 3, Autumn, p.105 – Attachment 2). The yellow sect of Tibetan Buddhism is more commonly known as Gelug but is also known as Geluk, Gelugpa, Gelukpa, Gelug pa, Geluk pa and the Yellow Hat sect. -

Guru Padmasambhava and His Five Main Consorts Distinct Identity of Christianity and Islam

Journal of Acharaya Narendra Dev Research Institute l ISSN : 0976-3287 l Vol-27 (Jan 2019-Jun 2019) Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts distinct identity of Christianity and Islam. According to them salvation is possible only if you accept the Guru Padmasambhava and his five main Consorts authority of their prophet and holy book. Conversely, Hinduism does not have a prophet or a holy book and does not claim that one can achieve self-realisation through only the Hindu way. Open-mindedness and simultaneous existence of various schools Heena Thakur*, Dr. Konchok Tashi** have been the hall mark of Indian thought. -------------Hindi----cultural ties with these countries. We are so influenced by western thought that we created religions where none existed. Today Abstract Hinduism, Buddhism and Jaininism are treated as Separate religions when they are actually different ways to achieve self-realisation. We need to disengage ourselves with the western world. We shall not let our culture to This work is based on the selected biographies of Guru Padmasambhava, a well known Indian Tantric stand like an accused in an alien court to be tried under alien law. We shall not compare ourselves point by point master who played a very important role in spreading Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. He is with some western ideal, in order to feel either shame or pride ---we do not wish to have to prove to any one regarded as a Second Buddha in the Himalayan region, especially in Tibet. He was the one who revealed whether we are good or bad, civilised or savage (world ----- that we are ourselves is all we wish to feel it for all Vajrayana teachings to the world. -

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Tibetan Tra- Ditions As a Citadel of Learning and Excellence

BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID ITHACA, NY 14851 Permit No. 746 Deliver to current resident ORDER FROM OUR NEW SNOW LION TOLL FREE NUMBER 1-800-950-0313 NEWSLETTER & CATALOG SNOW LION PUBLICATIONS PO BOX 6483, ITHACA, NY 14851, (607)-273-8506 VOLUME 4, NUMBER 1 H.H. SAKYA TRIZIN VISITS AMERICA In the Dehra Dun valley nestled between the Himalaya and Shiva- lik mountain ranges below the small Indian town of Rajpur, one finds a modest house surrounded by fruit trees. Here is the home of His Holi- ness Sakya Trizin, the crown-lama of the Sakya Order, His Consort, Damo Kushola, and their two sons, Ratna Vajra and Jnana Vajra. A far cry from the 80-room Dolma Palace of Sakya in Tibet, it nonetheless serves as His Holiness' main resi- dence and office as He guides the Sakya Order in both spiritual and temporal matters through the un- certain years of exile. A small way further down the treelined avenue of the Fajpur Road, one will often see red-robed monks waiting for a bus or busy with activities at the Sakya Center, the first Sakya monastery estab- lished in India. In the foothills over- looking Rajpur, one will find the advanced teacher-training facility, the Sakya College, which has won H.H. THE DALAI LAMA TO renown among all four Tibetan tra- ditions as a citadel of learning and excellence. A two-hour bus trip GIVE DZOGCHEN TEACHINGS from nearby Dehra Dun will bring one to the Sakya settlement of AND EMPOWERMENT OF Puruwalla, where refugee lay people form and make handicrafts, preserv- H.H.