Online Consumer Reviews in the Restaurant Industry !

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Social Media by Airports

JAIRM, 2012 – 2(2), 67-85 Online ISSN: 2014-4806 - Print ISSN: 2014-4865 http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jairm.9 Use of social media by airports Nigel Halpern Molde University College – Specialized University in Logistics (Norway) [email protected] Received July, 2012 Accepted September, 2012 Abstract Purpose: This study investigates use of social media by airports according to geographical location of the airport, airport size, and airport ownership and operation. Design/methodology/approach: The study is based on a content analysis of airport websites. The sample consists of 1559 airports worldwide that are members of Airports Council International (ACI). Findings: Almost one-fifth of airports use at least one type of social media; 13% use Facebook, 12% use Twitter, 7% use LinkedIn and 4% use YouTube. There is a greater use of social media by airports in North America and Europe, by larger airports, and by airports that are owned and operated by private interests. Originality/value: This study determines how widespread the use of social media is by airports. The degree to which airports and their customers actually use social media is also determined. Researchers can use the approach and findings of this study as a basis for investigating trends over time. Airport managers can use the findings to inform their own social media decisions. Keywords: Airports, marketing communications, social media 67 Journal of Airline and Airport Management 2(2), 67-85 1. Introduction Airports are increasingly embracing social media as a means of communication (Twentyman, 2010) and there are now numerous examples of airports offering the opportunity to ‘Like’ them on Facebook, ‘Follow’ them on Twitter and ‘View’ videos and photos about them on YouTube and Flickr. -

Hi-Media Advertising Rolls out Hi-Media Video in Europe

Press release Hi-media Advertising rolls out Hi-media Video in Europe Paris, February 16, 2011 – Online media group Hi-media (Code ISIN FR0000075988 - HIM, HIM.FR), the European leader in monetizing the Internet audience, announces the launch of Hi-media Video in Europe. Hi-media Video: exclusive online advertising video format Following the launch of Hi-media Mobile last June, Hi-media Advertising continues to develop new services, the latest being Hi-media Video. This new offering gives European advertisers access to a wide range of high-impact formats geared to all types of communication: - “In-Stream” (pre-roll, post-roll and overlay) functions to insert ad spots into website video content: with over 60 million videos viewed each month in Europe1, Hi-media offers its advertisers a video network on websites concentrated mainly in the Entertainment and News verticals, including jeuxvideo.com, sbs6.nl, RTL.fr, universal-music.de, cinemaxx.de, zappinternet.com or football-league.co.uk. - “In-Ad” functions programmable on IAB standard formats: Hi-media network attracts 138 million unique users2 per month in Europe including audiences of leading websites such as LeBonCoin.fr, Meetic, Fun Radio or Auto Plus in France, The Independent in the United Kingdom, erdbeerlounge.de and Qype in Germany, alfemminile.com in Italy or Autoscout24 in Spain. - Dedicated mobile video features (“in-banner” or “in-app”) offer, with an advertising inventory of over 100 million ad impressions3 a month. The Hi-media Mobile network encompasses a range of exclusive mobile Internet sites including RTL2, Rue89 and Foot365 in France, Shazam and Nimbuzz in Italy, DeTelegraaf and Vodafone Live in the Netherlands, or Netlog and Qype in Spain. -

European Technology, Media & Telecommunications Monitor

European Technology, Media & Telecommunications Monitor Market and Industry Update Fourth Quarter 2012 Piper Jaffray European TMT Team: Eric Sanschagrin Managing Director Head of European TMT [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8420 Stefan Zinzen Principal [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8418 Jessica Harneyford Associate [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8416 Peter Shin Analyst [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8444 Julie Wright Executive Assistant [email protected] +44 (0) 207 796 8427 TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS MONITOR Market and Industry Update Selected Piper Jaffray 2012 TMT Transactions 2 This report may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose without the written consent of Piper Jaffray. © 2013 Piper Jaffray Ltd. All rights reserved. TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS MONITOR Market and Industry Update Contents 1. Internet and Digital Media A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 2. Software and IT Services A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 3. Communications Technology And Hardware A. Trading Update B. Transaction Update C. Public Market Trading Multiples 4. Equity Capital Markets and M&A Update 3 This report may not be reproduced, redistributed or passed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose without the written consent of Piper Jaffray. © 2013 Piper Jaffray Ltd. All rights reserved. TECHNOLOGY, MEDIA &TELECOMMUNICATIONS -

YELP INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2013 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition period from to Commission file number: 001-35444 YELP INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 20-1854266 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 140 New Montgomery Street, 9 th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (415) 908-3801 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Class A Common Stock, par value $0.000001 per share New York Stock Exchange LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES NO Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES NO Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Online Consumer Reviews in the Restaurant Industry Kevin Mellet, Thomas Beauvisage, Jean Samuel Beuscart, Marie Trespeuch

A ‘Democratization’ of Markets? Online Consumer Reviews in the Restaurant Industry Kevin Mellet, Thomas Beauvisage, Jean Samuel Beuscart, Marie Trespeuch To cite this version: Kevin Mellet, Thomas Beauvisage, Jean Samuel Beuscart, Marie Trespeuch. A ‘Democratization’ of Markets? Online Consumer Reviews in the Restaurant Industry. Valuation Studies, Linköping University Electronic Press 2014, 2 (1), pp.5 - 41. 10.3384/vs.2001-5992.14215. hal-02947884 HAL Id: hal-02947884 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02947884 Submitted on 24 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Valuation Studies 2(1) 2014: 5–41 ! A “Democratization” of Markets? Online Consumer Reviews in the Restaurant Industry ! Kevin Mellet*, Thomas Beauvisage, Jean-Samuel Beuscart, and Marie Trespeuch Abstract This article examines the promise of market democratization conveyed by consumer rating and review websites in the restaurant industry. Based on interviews with website administrators and data from the main French platforms, we show that review websites contribute to the democratization of restaurant criticism, which frst started in the 1970s, both by including a greater variety of restaurants in the reviews, and by broadening participation, opening restaurant reviewing to all. -

Online Travel: the Internet Is the Key Sales Channel for Tour Operators

ITB Berlin 2009 Special Press Release: Online Travel ITB Berlin Special Press Release 08 / 2009 ITB Berlin 2009 March 11 to 15 Online Travel: The Internet is the key sales channel for tour operators Author: Isabel Bommer 1 ITB Berlin 2009 Special Press Release: Online Travel Market and technology trends in digital travel sales Social networking, semantic searches, crowd sourcing, microblogging, and video content: the Internet is developing at lightning pace. Current trends, which today employ online pioneers and e-business developers, are also directly relevant for the tourist sector. In particular, in the main travel markets, the Internet is a targeted way of becoming the most important channel for holiday sales, information and recommendations. The current uncertain economic climate will not stop this trend, although it is likely to require strategic concentration on profitable e-travel applications. The ITB Berlin 2009 highlights the latest challenges and opportunities in online travel sales – with the ITB Future Day, over 130 Travel Technology exhibitors and PhoCusWright@ITB Berlin, the industry’s leading international Travel Technology Congress. In 2008, Europe’s travel sector posted sales of almost 246 billion euros – the largest travel market in the world. In 2007, the sector grew twice as fast as the remainder of Europe’s economy. Almost one third of capacity was ultimately due to Internet sales. The unique feature was that online travel business showed double-digit growth rates (2008: 19 %) and was considerably faster than offline business and the European travel market as a whole (2008: 3 %) (Source: PhoCusWright’s European Online Travel Overview Fourth Edition 2008). -

ACT! by Sage and Social CRM – Part 1 Connecting with Your Customers: a Guide to Social Media

| Whitepaper ACT! by Sage and Social CRM – Part 1 Connecting with Your Customers: A Guide to Social Media ACT! by Sage Table of Contents Social Media and Contact Management Software ...................... 3 What is social media? ................................................................... 3 How is social media being used by businesses? ....................... 3 Why should you sit up and take notice? ..................................... 4 Using customers to generate prospects ....................................................... 4 Gaining insight to improve customer relations ............................................ 5 Managing your reputation online ................................................................... 5 How can you get started? ............................................................. 6 Step one – do your homework ....................................................................... 6 Step two – don’t just jump in .......................................................................... 6 Step three – create your social profiles ........................................................ 6 Step four – managing your reputation .......................................................... 7 Step five – use a contact manager to build relationships ........................... 7 Social media checklist .................................................................................... 9 Useful resources ............................................................................................. 9 Social media -

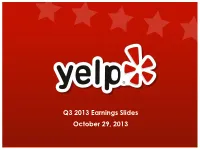

Q3 2013 Earnings Slides October 29, 2013 Strong Growth in Multiple Sources of Revenue

Q3 2013 Earnings Slides October 29, 2013 Strong Growth in Multiple Sources of Revenue ($M) $150 Other Brand Local $137.6M $125 $100 $83.3M $75 $61.2M $50 $47.7M $36.4M $25.8M $25 $0 2009 2010 2011 2012 Q3'12 Q3'13 Compelling Metrics* Cumulative Reviews Unique Visitors** Active Local Biz Accts1 47.3M 117M 42% 41% y/y y/y 57.2K 61% y/y 33.3M 84M 35.5K Sep 30, 2012 Sep 30, 2013 Q3'12 Q3'13 Q3'12 Q3'13 1 number of active local business accounts from which we recognized revenue during the period * Note that the review and paying local business accounts metrics for Q3 2013 include integrated Qype markets: France, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Brazil and the UK. ** Per Google Analytics, average number of monthly unique visitors over a given three-month period Cohort Analysis – Local Revenue Average Year-Over-Year Year-Over-Year Cumulative Growth in Average Local Growth in Reviews Average Advertising Average Local Number of As of Sep 30, 2013 Cumulative Revenue Q3 2013 Advertising U.S. Market Cohort Yelp Markets (1) (2) Reviews (3) (4) Revenue (5) 2005 – 2006 6 3,396 35% $3,832 57% Cohort 2007 – 2008 14 715 35% $954 74% Cohort 2009 – 2010 18 221 54% $213 99% Cohort (1) A Yelp market is defined as a city or region in which we have hired a Community (4) Average local advertising revenue is defined as the total local advertising Manager. revenue from businesses in the cohort over the three-month period ended (2) Average cumulative reviews is defined as the total cumulative reviews of the cohort September 30, 2013 (in thousands) divided by the number of markets in the as of September 30, 2013 (in thousands) divided by the number of markets in the cohort. -

Market Consequences of ICT Innovations

ifo Beiträge 70 zur Wirtschaftsforschung Market Consequences of ICT Innovations Constantin Mang Institut Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München e.V. Herausgeber der Reihe: Clemens Fuest Schriftleitung: Chang Woon Nam ifo Beiträge 70 zur Wirtschaftsforschung Market Consequences of ICT Innovations Constantin Mang Institut Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der Universität München e.V. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar ISBN-13: 978-3-95942-017-4 Alle Rechte, insbesondere das der Übersetzung in fremde Sprachen, vorbehalten. Ohne ausdrückliche Genehmigung des Verlags ist es auch nicht gestattet, dieses Buch oder Teile daraus auf photomechanischem Wege (Photokopie, Mikrokopie) oder auf andere Art zu vervielfältigen. © ifo Institut, München 2016 Druck: ifo Institut, München ifo Institut im Internet: http://www.cesifo-group.de Preface This volume was prepared by Constantin Mang while he was working at the Ifo Institute. It was completed in 2014 and accepted as a doctoral thesis by the Department of Economics at the University of Munich. It includes a short introduction and four self-contained chapters that focus on ICT innovations in different markets. Chapter 1 gives a short introduction into the topic and lays out some general aspects about the methodological frameworks used in this volume. Chapter 2 is focused on the effects of broadband Internet on the housing market in order to quantify the value of broadband access in terms of a premium on housing rents. Methodologically, the chapter uses micro data from Germany’s largest online platform for real estate advertisements and estimates a hedonic model with rent prices. -

Knowledge Management in Web 2.0

Qype Knowledge Management in Web 2.0 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 1 Agenda 1. What is Qype 2. Structure 3. Content 4. Competitors 5. Access the data 6. Using the data 7. Review 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 2 What is Q ualityH ype Portal for reviews and recommendations of places and services Write reviews and make your voice heard Connect with other people Make Qype work for your business Founded November 2005 in Hamburg Largest user-generated local review site in Europe Market leader in France, Germany and UK Available in 9 countries in 6 languages: More than 7 million users per month (1.76m unique users in Germany) 250,000 members 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 3 Structure 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 4 Structure 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 5 Structure 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 6 Structure 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 7 Structure 02.06.2009 | Computer Science Department | Ubiquitous Knowledge Processing Lab | Benedikt Conrad | 8 Content - Overview Reviews, events, guides, groups > 1.1m reviews and guides > 15,000 towns and cities Photos, and -

Turning Buzz Into Gold How Pioneers Create Value from Social Media

Turning buzz into gold How pioneers create value from social media Turning buzz into gold How pioneers create value from social media Note to the reader McKinsey has conducted a survey about social media excellence among almost 200 German companies. Throughout this brochure, the hand symbol highlights results from this survey. Turning buzz into gold How pioneers create value from social media 5 There is no strength in numbers, or so Uriah Heep would have us believe. But certainly, the power of the many helps to get noticed in this noisy world of ours. In the second half of the 20th century, both Christianity and Islam hit the mark of a billion followers. To date, only two national states have breached this barrier: China and India. In all probability, Facebook will be the next community to achieve that feat, with some 900 million monthly active users as of March 2012. Of course, an online social network is neither a church nor a country. But to many of its members, it might be a little bit of both. Social media is big, and it’s growing faster than any other technology before. Broad cast radio took almost 40 years to reach an audience of 50 million, and TV still took more than a decade. Both Twitter and Facebook made it in less than a year (Exhibit 1), and Pinterest, currently the fastestgrowing social media platform, may be the next to join their ranks. Every day, social network users spend more than 10 billion minutes on Facebook, watch 4 billion videos on YouTube, and send 340 million tweets. -

YELP INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2013 OR c TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition period from to Commission file number: 001-35444 YELP INC. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 20-1854266 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 140 New Montgomery Street, 9th Floor San Francisco, California 94105 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (415) 908-3801 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Class A Common Stock, par value $0.000001 per share New York Stock Exchange LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. YES x NO o Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. YES o NO x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.