Oxyuranus Microlepidotus, Elap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myths Surrounding Snakes

MYTHS SURROUNDING SNAKES MYTH 1: Bites from baby venomous snakes are more dangerous than those from adults because they always deliver a full dose of venom. The legend goes that young snakes have not yet learned how to control the amount of venom they inject. They are therefore more dangerous than adult snakes, which will restrict the amount of venom they use in a bite or “dry bite”. This is simply untrue and all the evidence points towards bites from adults being more severe. Tests have shown that juvenile snakes can control their venom just as much as adults. Furthermore lets consider the following factors: adults have significantly larger fangs to deliver their venom and considerably more venom available than a juvenile. Therefore if a juvenile has venom glands only big enough to hold a 2ml of venom compared to an adult that can hold 30ml or more, then the bite from an adult will always have the potential to be more severe. I presume the reason this myth came into existence was to dissuade people from having a carefree attitude towards the potential dangers of a juvenile snake. The moral of the story is to treat every snake as a potentially dangerous and never expose your self to a situation where a snake of any size can bite you. MYTH 2: If you see a snake they’ll always be more Although it is possible to see more than one snake, for the most part this statement is untrue. Snakes are solitary animals for most of their lives so generally you will only ever encounter individuals. -

Common Snakes of the Fraser Coast

Chris Muller pictured above Common Snakes of the Fraser Coast By Jenny Watts At the end of an informative and entertaining talk by Chris Muller in front of 35 people I was left feeling how lucky we are to have a such an knowledgeable and reptile passionate person living in our area. We want Chris to come and talk to us more! Chris is currently working in a team contracted by our local council to revegetate natural areas. But he came to talk to us about his passion - snakes – and the association he has that goes back a long way. Chris’s dad was a scientist and Chris grew up around snakes. He was a member of a National Parks and Wildlife crew catching snakes even before he left school! Interspersed with information about the most commonly found snakes in our backyards (he included a legless lizard as well as pythons, tree snakes, freshwater keelbacks and a number of Elapids – venomous snakes) Chris told us hairy stories of snake catching. The most jaw dropping was handling a death adder while driving a tourist bus (“I didn’t realise they were so strong”) and extracting a big brown from under the bonnet of a car (“lucky it was contained by the radiator grill as it was directly under me”). So here are some of those snakes and some information: Burtons Legless Lizard This is a very common reptile found in our backyards where it is an aggressive feeder of small skinks. It is often mistaken for a snake but is a lizard – having ear holes, a broad flat tongue and small vestigial legs. -

Creatures That Can Kill You 5

AROUND THE WORLD PREVIEWITH WSNAKES Preview Snakes slither through nearly every country on Earth. Most snakes are harmless, but some of them are are anything but. In this chapter, we will travel from India to Australia to Africa. The scariest, the deadliest, and the most feared snakes—they’re all here! 1 Around The World With Snakes AROUNDIn a rice THEfield in WORLD India, a young WITH worker namedSNAKES Abhay stepped carefully around the plants he tended. As always, Abhay listened for any quick rustling through the leaves or, worse yet, In a ricea sudden field hissing. in India, But as thea youngsky began workergrowing named Abhaydark stepped with rain carefully clouds, Abhay around became the careless plants he in his hurry to finish his job. He moved quickly tended.through As always, some tallerAbhay plants listened that blocked for any his quick rustlingview through of the ground. the leaves or, worse yet, a sudden hissing. But as the sky began growing dark with rain clouds, Abhay became careless in his hurry to finish his job. He moved quickly through some taller plants that blocked his view of the ground. Then, just at the edge of the field, Abhay felt something very strange. It was as if a thick cord of rope had been yanked beneath his left foot. 3 4 MARIE NOBLE In that same instant, Abhay saw a flash of brown and gold rise up before him—the dreaded Indian cobra. It was not the first time he had seen this terrifying snake. From the time he was a young child, Abhay had often seen these 6- to 10-foot snakes slithering through the village where he lived. -

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “Pit Vipers” Whose Fangs Fold up Against the Roof of Their Mouth, Such As Rattlesnakes, Copperheads, and Cottonmouths

FAMILY VIPERIDAE: VENOMOUS “pit vipers” whose fangs fold up against the roof of their mouth, such as rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths COPPERHEAD—Agkistrodon contortrix Uncommon to common. Copperheads are found in wet wooded areas, high areas in swamps, and mountainous habitats, although they may be encountered occasionally in most terrestrial habitats. Adults usually are 2 to 3 ft. long. Their general appearance is light brown or pinkish with darker, saddle-shaped crossbands. The head is solid brown. Their leaf-pattern camouflage permits copperheads to be sit- Juvenile copper- heads and-wait predators, concealed not only from their prey but also from their enemies. Copperheads feed on mice, small birds, lizards, snakes, amphibians, and insects, especially cicadas. Like young cottonmouths, baby copperheads have a bright yellow tail that is used to lure small prey animals. 0123ft. Heat-sensing “pit” characteristic of pit vipers CANEBRAKE OR TIMBER RATTLESNAKE—Crotalus horridus Mountain form Common. This species occupies a wide diversity of terrestrial habitats, but is found most frequently in deciduous forests and high ground in swamps. Heavy-bodied adults are usually 3 to 4, and occasionally 5, ft. long. Their basic color is gray with black crossbands that usually are chevron-shaped. Timber rattlesnakes feed on various rodents, rabbits, and occasionally birds. These rattlesnakes are generally passive if not disturbed or pestered in some way. When a rattlesnake is Coastal plain form encountered, the safest reaction is to back away--it will not try to attack you if you leave it alone. 012345 ft. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE— Crotalus adamanteus Rare. This rattlesnake is found in both wet and dry terrestrial habitats including palmetto stands, pine woods, and swamp margins. -

Proteomic and Genomic Characterisation of Venom Proteins from Oxyuranus Species

This file is part of the following reference: Welton, Ronelle Ellen (2005) Proteomic and genomic characterisation of venom proteins from Oxyuranus species. PhD thesis, James Cook University Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/11938 Chapter 1 Introduction and literature review Chapter 1 Introduction and literature review 1.1 INTRODUCTION Animal venoms are an evolutionary adaptation to immobilise and digest prey and are used secondarily as a defence mechanism (Tu and Dekker, 1991). Intriguingly, evolutionary adaptations have produced a variety of venom proteins with specific actions and targets. A cocktail of protein and peptide toxins have varying molecular compositions, and these unique components have evolved for differing species to quickly and specifically target their prey. The compositions of venoms differ, with components varying within the toxins of spiders, stinging fish, jellyfish, octopi, cone shells, ticks, ants and snakes. Toxins have evolved for the varying mode of actions within different organisms, yet many enzymes are common to different venoms including L-amino oxidases, esterases, aminopeptidases, hyaluronidases, triphosphatases, alkaline phosphomonoesterases, 2 2 phospholipases, phosphodiesterases, serine-metalloproteases and Ca +IMg +-activated proteases. The enzymes found in venoms fall into one or more pharmacological groups including those which possess neurotoxic (causing paralysis or interfering with nervous system function), myotoxic (damaging muscle), haemotoxic (affecting the blood, -

Snakebite: the World's Biggest Hidden Health Crisis

Snakebite: The world's biggest hidden health crisis Snakebite is a potentially life-threatening neglected tropical disease (NTD) that is responsible for immense suffering among some 5.8 billion people who are at risk of encountering a venomous snake. The human cost of snakebite Snakebite Treatment Timeline Each year, approximately 5.4 million people are bitten by a snake, of whom 2.7 million are injected with venom. The first snake antivenom This leads to 400,000 people being permanently dis- produced, against the Indian Cobra. abled and between 83,000-138,000 deaths annually, Immunotherapy with animal- mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. 1895 derived antivenom has continued to be the main treatment for snakebite evenoming for 120 years Snakebite: both a consequence and a cause of tropical poverty The Fav-Afrique antivenom, 2014 produced by Sanofi Pasteur (France) Survivors of untreated envenoming may be left with permanently discontinued amputation, blindness, mental health issues, and other forms of disability that severely affect their productivity. World Health Organization Most victims are agricultural workers and children in 2018 (WHO) lists snakebite envenoming the poorest parts of Africa and Asia. The economic as a neglected tropical disease cost of treating snakebite envenoming is unimaginable in most communities and puts families and communi- ties at risk of economic peril just to pay for treatment. WHO launches a strategy to prevent and control snakebite envenoming, including a program targeting affected communities and their health systems Global antivenom crisis 2019 The world produces less than half of the antivenom it The Scientific Research Partnership needs, and this only covers 57% of the world’s species for Neglected Tropical Snakbites of venomous snake. -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

Is the Sonoran Coral Snake Dangerous? How Do I Avoid Being Bitten by A

SNAKES How can I tell if a snake is venomous? Is the Sonoran coral snake dangerous? How do I avoid being bitten by a snake? Is a snake still dangerous after it is dead? What happens when a person is bitten by a venomous snake? Is it possible to remove the venom after I’ve been bitten by a snake? What should I do if I am bitten by a snake? What shouldn’t I do if I am bitten by a snake? Is it important to know which type of venomous snake bit me to get appropriate treatment? What treatment am I likely to receive if I am bitten by a venomous snake? What medications should I avoid while being treated for a snakebite? Is it possible to become immune to snake venom? How can I tell if a snake is venomous? Most venomous snakes in the United States belong to the family of snakes sometimes referred to as pit vipers. These snakes, which belong to the Family Crotalinae, include rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths (water moccasins). All pit vipers in Arizona are rattlesnakes. These snakes are most easily identified by the presence of a rattle on their tail and a triangular shaped head. However, some young snakes may not have developed a rattle yet but still possess venom. When in doubt, avoid contact! Aside from pit vipers, all other venomous snakes native to the U.S. are coral snakes, which belong to the Elapid family of snakes. Coral snakes found in the Eastern U.S. can be very dangerous to humans, but the Sonoran coral snake, found in Arizona, is not. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

Very Venomous, But...- Snakes of the Wet Tropics

No.80 January 2004 Notes from Very venomous but ... the Australia is home to some of the most venomous snakes in the world. Why? Editor It is possible that strong venom may little chance to fight back. There are six main snake families have evolved chiefly as a self-defence in Australia – elapids (venomous strategy. It is interesting to look at the While coastal and inland taipans eat snakes, the largest group), habits of different venomous snakes. only mammals, other venomous colubrids (‘harmless’ snakes) Some, such as the coastal taipan snakes feed largely on reptiles and pythons, blindsnakes, filesnakes (Oxyuranus scutellatus), bite their frogs. Venom acts slowly on these and seasnakes. prey quickly, delivering a large amount ‘cold-blooded’ creatures with slow of venom, and then let go. The strong metabolic rates, so perhaps it needs to Australia is the only continent venom means that the prey doesn’t be especially strong. In addition, as where venomous snakes (70 get far before succumbing so the many prey species develop a degree of percent) outnumber non- snake is able to follow at a safe immunity to snake venom, a form of venomous ones. Despite this, as distance. Taipans eat only mammals – evolutionary arms race may have been the graph on page one illustrates, which are able to bite back, viciously. taking place. very few deaths result from snake This strategy therefore allows the bites. It is estimated that between snake to avoid injury. … not necessarily deadly 50 000 and 60 000 people die of On the other hand, the most Some Australian snakes may be snake bite each year around the particularly venomous, but they are world. -

Testing the Toxicofera: Comparative Reptile Transcriptomics Casts Doubt on the Single, Early Evolution of the Reptile Venom Syst

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/006031; this version posted June 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title page 2 3 Title: 4 Testing the Toxicofera: comparative reptile transcriptomics casts doubt on the single, early 5 evolution of the reptile venom system 6 7 Authors: 8 Adam D Hargreaves1, Martin T Swain2, Darren W Logan3 and John F Mulley1* 9 10 Affiliations: 11 1. School of Biological Sciences, Bangor University, Brambell Building, Deiniol Road, 12 Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2UW, United Kingdom 13 14 2. Institute of Biological, Environmental & Rural Sciences, Aberystwyth University, 15 Penglais, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3DA, United Kingdom 16 17 3. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge, CB10 1HH, United Kingdom 18 19 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] 20 21 22 Author email addresses: 23 John Mulley - [email protected] 24 Adam Hargreaves - [email protected] 25 Darren Logan - [email protected] 26 Martin Swain - [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/006031; this version posted June 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

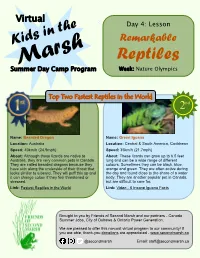

Reptiles Summer Day Camp Program Week: Nature Olympics

Virtual Day 4: Lesson Kids in the Remarkable Marsh Reptiles Summer Day Camp Program Week: Nature Olympics Top Two Fastest Reptiles in the World 2nd Name: Bearded Dragon Name: Green Iguana Location: Australia Location: Central & South America, Caribbean Speed: 40km/h (24.9mph) Speed: 35km/h (21.7mph) About: Although these lizards are native to About: These lizards can grow up to 6.5 feet Australia, they are very common pets in Canada. long and can be a wide range of different They are called bearded dragons because they colours. Sometimes they can be black, blue, have skin along the underside of their throat that orange and green. They are often active during looks similar to a beard. They will puff this up and the day and found close to the shore of a water it can change colour if they feel threatened or body. They are another popular pet in Canada, stressed. but are difficult to care for. Link: Fastest Reptiles in the World Link: Video - 6 Insane Iguana Facts Brought to you by Friends of Second Marsh and our partners - Canada Summer Jobs, City of Oshawa & Ontario Power Generation. We are pleased to offer this no-cost virtual program to our community! If you are able, thank-you donations are appreciated - www.secondmarsh.ca @secondmarsh Email: [email protected] Remarkable Reptiles World’s Most Venomous Snake World’s Most Dangerous Lizard (Chan, 2007) (Wahlberg, 2014) Name: Inland Taipan Name: Gila Monster Location: Australia Location: Mexico and Southwestern USA Size: 78.7 inches (200cm) Size: 24 inches (60cm) About: Even though the inland taipan is About: These colourful looking lizards carry considered the most venomous snake in the enough venom that could kill two adult humans.