Special Collections Exhibition Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingston Lacy Illustrated List of Pictures K Introduction the Restoration

Kingston Lacy Illustrated list of pictures Introduction ingston Lacy has the distinction of being the however, is a set of portraits by Lely, painted at K gentry collection with the earliest recorded still the apogee of his ability, that is without surviving surviving nucleus – something that few collections rival anywhere outside the Royal Collection. Chiefly of any kind in the United Kingdom can boast. When of members of his own family, but also including Ralph – later Sir Ralph – Bankes (?1631–1677) first relations (No.16; Charles Brune of Athelhampton jotted down in his commonplace book, between (1630/1–?1703)), friends (No.2, Edmund Stafford May 1656 and the end of 1658, a note of ‘Pictures in of Buckinghamshire), and beauties of equivocal my Chamber att Grayes Inne’, consisting of a mere reputation (No.4, Elizabeth Trentham, Viscountess 15 of them, he can have had little idea that they Cullen (1640–1713)), they induced Sir Joshua would swell to the roughly 200 paintings that are Reynolds to declare, when he visited Kingston Hall at Kingston Lacy today. in 1762, that: ‘I never had fully appreciated Sir Peter That they have done so is due, above all, to two Lely till I had seen these portraits’. later collectors, Henry Bankes II, MP (1757–1834), Although Sir Ralph evidently collected other – and his son William John Bankes, MP (1786–1855), but largely minor pictures – as did his successors, and to the piety of successive members of the it was not until Henry Bankes II (1757–1834), who Bankes family in preserving these collections made the Grand Tour in 1778–80, and paid a further virtually intact, and ultimately leaving them, in the visit to Rome in 1782, that the family produced astonishingly munificent bequest by (Henry John) another true collector. -

Incisioni, Richiestissime Da Un Mercato Molto Fiorente, Giunge Ora Una Rassegna Di Rilevante Interesse, Che Si Apre Oggi Alle 17 Nei Saloni Della Biblioteca Palatina

Parmigianino e l’incisione <Padre dell'acquaforte italiana> l'ha definito Mary Pittaluga. E Giovanni Copertini ha specificato <Sebbene non si possa più considerare come l'inventore della tecnica dell'acquaforte, pure è da esserne stimato il creatore spirituale ché, con le sue stampe, ha insegnato agli artisti a trasfondere luce d'idealità in poche linee e in un tenue motivo di segni incrociati>. E' questo il lato meno noto del Parmigianino: incantevole pittore, straordinario disegnatore e anche abilissimo incisore; una caratteristica, quella di grafico, che nella grandiosa mostra allestita per celebrare il quinto centenario della nascita dell'artista passa un po' inosservata di fronte alla parata affascinante dei dipinti e dei disegni. Ad illuminare questo aspetto non secondario dell'attività del Parmigianino sia come autore diretto sia soprattutto come fornitore di disegni da trasformare in incisioni, richiestissime da un mercato molto fiorente, giunge ora una rassegna di rilevante interesse, che si apre oggi alle 17 nei saloni della Biblioteca Palatina (fino al 27 settembre) e che ha come titolo <Parmigianino tradotto. La fortuna di Francesco Mazzola nelle stampe di riproduzione tra il Cinquecento e l'Ottocento>. La correda un catalogo, pubblicato dalla Silvana Editoriale, comprendente la presentazione del direttore della Biblioteca Leonardo Farinelli, un approfondito saggio critico di Massimo Mussini e un'introduzione alle schede di Grazia Maria de Rubeis, responsabile del gabinetto delle stampe; il volume documenta tutte le incisioni <parmigianinesche> posseduta dalla Palatina, comprese quelle non esposte, cosicché assume un notevole valore scientifico in un settore ancora scarsamente esplorato con sistematicità. E' a Roma, dove si trasferisce nel 1524, che Francesco Mazzola entra nell'ambiente degli incisori fornendo disegni a Ugo da Carpi, considerato il padre della silografia, e a Jacopo Caraglio, incisore a bulino allievo di Marco Antonio Raimondi. -

Anecdotes of Painting in England : with Some Account of the Principal

C ' 1 2. J? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/paintingineng02walp ^-©HINTESS <0>F AEHJKTID 'oat/ /y ' L o :j : ANECDOTES OF PAINTING IN ENGLAND; WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THE PRINCIPAL ARTISTS; AND INCIDENTAL NOTES ON OTHER ARTS; COLLECTED BY THE LATE MR. GEORGE VERTUE; DIGESTED AND PUBLISHED FROM HIS ORIGINAL MSS. BY THE HONOURABLE HORACE WALPOLE; WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS BY THE REV. JAMES DALLAWAY. LONDON PRINTED AT THE SHAKSPEARE PRESS, BY W. NICOL, FOR JOHN MAJOR, FLEET-STREET. MDCCCXXVI. LIST OF PLATES TO VOL. II. The Countess of Arundel, from the Original Painting at Worksop Manor, facing the title page. Paul Vansomer, . to face page 5 Cornelius Jansen, . .9 Daniel Mytens, . .15 Peter Oliver, . 25 The Earl of Arundel, . .144 Sir Peter Paul Rubens, . 161 Abraham Diepenbeck, . 1S7 Sir Anthony Vandyck, . 188 Cornelius Polenburg, . 238 John Torrentius, . .241 George Jameson, his Wife and Son, . 243 William Dobson, . 251 Gerard Honthorst, . 258 Nicholas Laniere, . 270 John Petitot, . 301 Inigo Jones, .... 330 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD. Arms of Rubens, Vandyck & Jones to follow the title. Henry Gyles and John Rowell, . 39 Nicholas Stone, Senior and Junior, . 55 Henry Stone, .... 65 View of Wollaton, Nottinghamshire, . 91 Abraham Vanderdort, . 101 Sir B. Gerbier, . .114 George Geldorp, . 233 Henry Steenwyck, . 240 John Van Belcamp, . 265 Horatio Gentileschi, . 267 Francis Wouters, . 273 ENGRAVINGS ON WOOD continued. Adrian Hanneman, . 279 Sir Toby Matthews, . , .286 Francis Cleyn, . 291 Edward Pierce, Father and Son, . 314 Hubert Le Soeur, . 316 View of Whitehall, . .361 General Lambert, R. Walker and E. Mascall, 368 CONTENTS OF THE SECOND VOLUME. -

Che Si Conoscono Al Suo Già Detto Segno Vasari's Connoisseurship In

Che si conoscono al suo già detto segno Vasari’s connoisseurship in the field of engravings Stefano Pierguidi The esteem in which Giorgio Vasari held prints and engravers has been hotly debated in recent criticism. In 1990, Evelina Borea suggested that the author of the Lives was basically interested in prints only with regard to the authors of the inventions and not to their material execution,1 and this theory has been embraced both by David Landau2 and Robert Getscher.3 More recently, Sharon Gregory has attempted to tone down this highly critical stance, arguing that in the life of Marcantonio Raimondi 'and other engravers of prints' inserted ex novo into the edition of 1568, which offers a genuine history of the art from Maso Finiguerra to Maarten van Heemskerck, Vasari focused on the artist who made the engravings and not on the inventor of those prints, acknowledging the status of the various Agostino Veneziano, Jacopo Caraglio and Enea Vico (among many others) as individual artists with a specific and recognizable style.4 In at least one case, that of the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence engraved by Raimondi after a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, Vasari goes so far as to heap greater praise on the engraver, clearly distinguishing the technical skills of the former from those of the inventor: [...] So when Marcantonio, having heard the whole story, finished the plate he went before Baccio could find out about it to the Pope, who took infinite 1 Evelina Borea, 'Vasari e le stampe', Prospettiva, 57–60, 1990, 35. 2 David Landau, 'Artistic Experiment and the Collector’s Print – Italy', in David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print 1470 - 1550, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994, 284. -

English Female Artists

^ $525.- V ^ T R /S. / / \ * t {/<•/dti '/’rlk- Printed lor Hob'.Saryer.N?^ in Fleet Street ■ ENGLISH 'EMALE ART < rn us. Ei.LSK C. G) aYXO v A' £HOR Of •' QUi'JBKir OF 80N0 ' !,'TO. • • • VOL f. LONDON; ! OTHERS, S CATHERINE ST.. SXRAN I) 187C. (A'ii *1 ijkti r ;,d) * ENGLISH FEMALE ARTISTS. lBY ELLEN C. CLAYTON, AUTHOR OF “QUEENS OF SONG,” ETC. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I. I- LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 8 CATHERINE ST., STRAND. 1876. (All rights reserved.) TO (gHsabftlt Sltompisian THIS BOOK, A ROLL CALL OF HONOURABLE NAMES, is BY PERMISSION INSCRIBED, IN TESTIMONY OF ADMIRATION FOR HER GENIUS. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE Susannah Hornebolt. Lavinia Teerlinck ... ... ... 1 CHAPTER II. Anne Carlisle. Artemisia Gentileschi. The Sisters Cleyn 14 CHAPTER III. Anna Maria Carew. Elizabeth Neale. Mary More. Mrs. Boardman. Elizabeth Creed ... ... ... ... 35 CHAPTER IY. Mary Beale ... ... ... ... ... ... 40 CHAPTER Y. Susan Penelope Rose ... ... ... ... ... 54 CHAPTER VI. Anne Killigrew ... ... ... ... ... ... 59 CHAPTER VII. Maria Varelst ... ... ... ... ... ... 71 VI CONTENTS. CHAPTER VIII. PAGE Anne, Princess of Orange. Princess Caroline. Agatha Van- dermijn. Sarah Hoadley 78 CHAPTER IX. Elizabeth Blackwell 91 CHAPTER X. Mary Delany 96 CHAPTER XL Frances Reynolds 146 CHAPTER XII. Maria Anna Angelica Catherine Kauffman 233 CHAPTER XIII. Mary Moser 295 CHAPTER XIV. Maria Cecilia Louisa Cosway 314 CHAPTER XV. Amateurs: Temp. George the Third 336 CHAPTER XVI. The Close of the Eighteenth Century 359 CHAPTER XVII. The Earlier Years of the Nineteenth Century ... 379 CHAPTER XVIII. Mary Harrison. Anna Maria Charretie. Adelaide A. Maguire 410 LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL AUTHORITIES CONSULTED FOR THE FIRST VOLUME. Annual Registek. Abt Joubnal. -

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 the J

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 1 6 1. Dosso Dossi (Giovanni di Niccolò de Lutero) 2. Simon Bening Italian (Ferrarese), about 1490 - 1542 Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 NUDE NUDE A Myth of Pan, 1524 Flagellation of Christ, About 1525-30 Oil on canvas from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg Unframed: 163.8 × 145.4 cm (64 1/2 × 57 1/4 in.) Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) 83.PA.15 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 154v (83.ML.115.154v) 6 5 3. Simon Bening 4. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola) Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 Italian, 1503 - 1540 NUDE Border with Job Mocked by His Wife and Tormented by Reclining Male Figure, About 1526-27 NUDE Two Devils, about 1525 - 1530 Pen and brown ink, brown wash, white from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg heightening Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment 21.6 × 24.3 cm (8 1/2 × 9 9/16 in.) Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 84.GA.9 Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 155 (83.ML.115.155) October 10, 2018 Page 1 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ © 2018 J. -

Teaching Gallery Picturing Narrative: Greek Mythology in the Visual Arts

list of Works c Painter andré racz (Greek, Attic, active c. 575–555 BC) (American, b. Romania, 1916–1994) after giovanni Jacopo caraglio Siana Cup, 560–550 BC Perseus Beheading Medusa, VIII, 1945 Teaching gallery fall 2014 3 5 1 1 (Italian, c. 1500/1505–1565) Terracotta, 5 /8 x 12 /8" engraving with aquatint, 7/25, 26 /8 x 18 /4" after rosso fiorentino gift of robert Brookings and charles University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946 (Italian, 1494–1540) Parsons, 1904 Mercury, 16th century (after 1526) Marcantonio raimondi 1 Pen and ink wash on paper, 10 /8 x 8" ca Painter (Italian, c. 1480–c. 1530) gift of the Washington University (Greek, South Italian, Campanian) after raphael Department of art and archaeology, 1969 Bell Krater, mid-4th century BC (Italian, 1483–1520) 1 5 Terracotta, 17 /2 x 16 /8" Judgment of Paris, c. 1517–20 3 15 after gustave Moreau gift of robert Brookings and charles engraving, 11 /8 x 16 /16" Picturing narrative: greek (French, 1826–1898) Parsons, 1904 gift of J. lionberger Davis, 1966 Jeune fille de Thrace portant la tête d’Orphée (Thracian Girl Carrying the alan Davie school of orazio fontana Mythology in the visual arts Head of Orpheus), c. 1865 (Scottish, 1920–2014) (Italian, 1510–1571) 1 1 Oil on canvas, 39 /2 x 25 /2" Transformation of the Wooden Horse I, How Cadmus Killed the Serpent, c. 1540 7 5 University purchase, Parsons Fund, 1965 1960 Maiolica, 1 /8 x 10 /8" 1 1 Oil on canvas, 60 /8 x 72 /4" University purchase, elizabeth northrup after Marcantonio raimondi gift of Mr. -

FRANCIS BARLOW English Book Illustration

FRANCIS BARLOW First master of English book illustration EDWARD HODNETT EDWARD HODNETT FRANCIS BARLOW First Master of English Book Illustration UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Printed in Great Britain by The Scolar Press Ltd Ilkley, Yorkshire © Edward Hodnett 1978 ISBN O-52O-93409-O Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 76-55570 Preface i Francis Barlow’s Career 11 n Book Illustration in Plngland before 1700 35 h i Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder and the Tradition of Aesopic Fable Illustration 57 iv Francis Cleyn and John Ogilby 73 v The Minor Works of Barlow 89 vi Barlow’s Illustrations of Theophila by Edward Benlowes (1652) 112 v 11 The Interpretive Illustrations of Wenceslaus Hollar - Ogilby’s Aesop Paraphras'd (1665); his Aesopics and The Ephesian Matron (1668) 134 vin Barlow’s Aesop's Tables (1666) 167 ix Barlow’s Designs for Ogilby’s Aesopics and Androcleus (1668); his Life of Aesop Series (1687) 197 Bibliography Index 5 Actes and Monuments, 25, 39, 40, 64 B a r k e r , Robert, 114 Aesop: Five Centuries of Illustrated Fables, 6 5 B a r l o w , Francis Aesopic fables, 64-72 Aesopic ’s: or a Second Collection of Fables Aesopic's: or a Second Collection of Fables Paraphras’din Verse(i668), 96, 99, 106, 109, Paraphras’din Verse( 1668). See Hollar, 167, 197-202, 204, 222; see also Hollar Wenceslaus, and Barlow, Francis; (1673) Aesop’s Fables. With his life. In English French Ogilby, John ePLatine(1666), 13, 28, 93, 154, 167-96, 197, AesopiPhrygis, et aliorumfabulae(1565), 70 206,213, 222 Aesopi Phrygis Fabulae (1385), 209 Aesop’s Fables, etc. -

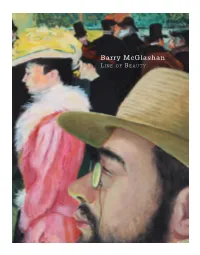

Barry Mcglashan L I N E O F B E a U T Y Barry Mcglashan L I N E O F B E a U T Y

Barry McGlashan L INE OF B EAUTY Barry McGlashan L INE OF B EAUTY 2–24 N OVEM B ER 2018 FOREWORD BY WALDEMAR JANUSZCZAK John Martin Gallery Barry’s World by Waldemar Januszczak Talk about a kid in a sweet shop! What evident fun Death of Ananias… Our job as viewers – our pleasure Barry McGlashan has had recreating and imagining as viewers – is to explore the details, make sense the studios of great artists. Let loose on the entire of them, puzzle over them, connect them, decipher history of art, free to pop into any studio he wants, them. Some of the pleasure you get from a Barry buzzing between geniuses and epochs like a bee McGlashan picture is the kind of pleasure you get collecting pollen, McGlashan paints pictures that from a Where’s Wally book. throb with the Hello! Magazine pleasure of sneaking into people’s houses and having a good gawp. In fact, artists taking on other artists is a genre with plenty of precedents. To give you an immediate Look, there’s Raphael with his mistress, La Fornerina, example, Rembrandt’s great self-portrait at Kenwood sitting on his knee while he paints her portrait! Look, House, the one with two mysterious circles looming there’s Leonardo at work on the Mona Lisa! And isn’t up behind him, was a deliberate riposte to the that the table around which Jesus and the Apostles celebrated Greek painter, Apelles, who was famous sat in the Last Supper? Look, it’s Toulouse Lautrec for being able to draw a perfect circle, freehand. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Dena Crosson Laura Carter (202) 842-6353 ** FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, Oct. 20, 1987 11:00 a.m. - 2:00 p.m. THE ART OF ROSSQ FIORENTINO TO OPEN AT NATIONAL GALLERY First U.S. Exhibition Ever Devoted Solely to 16th-century Italian Renaissance Artist October 1, 1987 - The first exhibition in the United States ever devoted solely to the works and designs of 16th-century Italian Renaissance artist Rosso Florentine opens Oct. 25 at the National Gallery of Art's West Building. Rosso Fiorentino Drawings, Prints and Decorative Arts consists of 117 objects, including 28 drawings by Rosso, 80 prints after his compositions, majolica and enamel platters, and tapestries made from his designs. On view through Jan. 3, 1988, the exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (1494-1540), best known as Rosso Fiorentino, worked in Florence from 1513 until 1524, when he went to Rome. He left the city during the infamous Sack of Rome in 1527, wandering about Italy until 1530, when he went to France to work for King Francis I at Fontainebleau. Rosso began his career with a style modeled on the art of the Florentine Renaissance, but he is now seen as one of the founders of the anticlassical style called Mannerism. An intense and eccentric individual, Rosso was internationally famous in the 16th century while today he is most readily recognized for his work at Fontainebleau and for the great impact of his Italian style on French art. -

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected]

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected] The subject of articles or notes is printed in CAPITAL letters; book and exhibition catalogue titles are given in italics; volume numbers are in Roman numerals and in bold face. Included in individual artist entries are authentic works, studio works, copies, attributions, etc., arranged in sequential order within the citations for each volume. When an author has written reviews, that designation appears at the end of the review citations. Names of collectors are in italics. Abbreviated names of Italian churches are alphabetized as if fully spelled out: "Rome, S. <San> Pietro in Montorio" precedes "S. <Santa> Maria del Popolo." Concordance of Master Drawings volumes and year of publication: I 1963 XII 1974 XXIII–XXIV 1985–86 XXXV 1997 XLVI 2008 II 1964 XIII 1975 XXV 1987 XXXVI 1998 XLVII 2009 III 1965 XIV 1976 XXVI 1988 XXXVII 1999 XLVIII 2010 IV 1966 XV 1977 XXVII 1989 XXXVIII 2000 XLIX 2011 V 1967 XVI 1978 XXVIII 1990 XXXIX 2001 L 2012 VI 1968 XVII 1979 XXIX 1991 XL 2002 LI 2013 VII 1969 XVIII 1980 XXX 1992 XLI 2003 LII 2014 VIII 1970 XIX 1981 XXXI 1993 XLII 2004 LIII 2015 IX 1971 XX 1982 XXXII 1994 XLIII 2005 LIV 2016 X 1972 XXI 1983 XXXIII 1995 XLIV 2006 LV 2017 XI 1973 XXII 1984 XXXIV 1996 XLV 2007 À l’ombre des frondaisons d’Arcueil: Dessiner un jardin du XVIIe siècle, exh. cat. by Xavier Salmon et al. Review. LIV: 397–404 A. S. -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected