Animation & Sequential Art Principles for Handheld Projector Interaction

Total Page:16

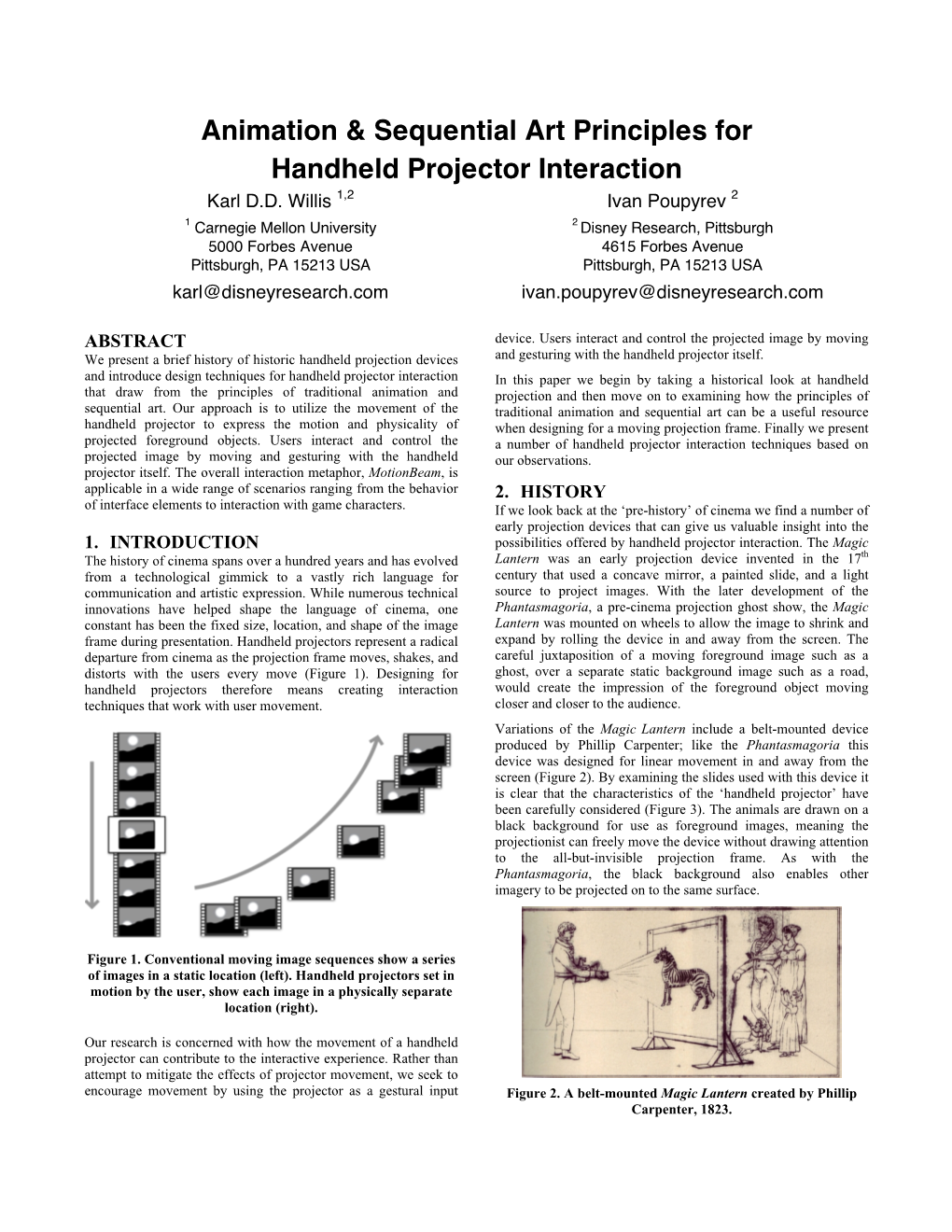

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breaking Down the “Cosine Fourth Power Law”

Breaking Down The “Cosine Fourth Power Law” By Ronian Siew, inopticalsolutions.com Why are the corners of the field of view in the image captured by a camera lens usually darker than the center? For one thing, camera lenses by design often introduce “vignetting” into the image, which is the deliberate clipping of rays at the corners of the field of view in order to cut away excessive lens aberrations. But, it is also known that corner areas in an image can get dark even without vignetting, due in part to the so-called “cosine fourth power law.” 1 According to this “law,” when a lens projects the image of a uniform source onto a screen, in the absence of vignetting, the illumination flux density (i.e., the optical power per unit area) across the screen from the center to the edge varies according to the fourth power of the cosine of the angle between the optic axis and the oblique ray striking the screen. Actually, optical designers know this “law” does not apply generally to all lens conditions.2 – 10 Fundamental principles of optical radiative flux transfer in lens systems allow one to tune the illumination distribution across the image by varying lens design characteristics. In this article, we take a tour into the fascinating physics governing the illumination of images in lens systems. Relative Illumination In Lens Systems In lens design, one characterizes the illumination distribution across the screen where the image resides in terms of a quantity known as the lens’ relative illumination — the ratio of the irradiance (i.e., the power per unit area) at any off-axis position of the image to the irradiance at the center of the image. -

Moving Pictures: the History of Early Cinema by Brian Manley

Discovery Guides Moving Pictures: The History of Early Cinema By Brian Manley Introduction The history of film cannot be credited to one individual as an oversimplification of any his- tory often tries to do. Each inventor added to the progress of other inventors, culminating in progress for the entire art and industry. Often masked in mystery and fable, the beginnings of film and the silent era of motion pictures are usually marked by a stigma of crudeness and naiveté, both on the audience's and filmmakers' parts. However, with the landmark depiction of a train hurtling toward and past the camera, the Lumière Brothers’ 1895 picture “La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon” (“Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory”), was only one of a series of simultaneous artistic and technological breakthroughs that began to culminate at the end of the nineteenth century. These triumphs that began with the creation of a machine that captured moving images led to one of the most celebrated and distinctive art forms at the start of the 20th century. Audiences had already reveled in Magic Lantern, 1818, Musée des Arts et Métiers motion pictures through clever uses of slides http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Magic-lantern.jpg and mechanisms creating "moving photographs" with such 16th-century inventions as magic lanterns. These basic concepts, combined with trial and error and the desire of audiences across the world to see entertainment projected onto a large screen in front of them, birthed the movies. From the “actualities” of penny arcades, the idea of telling a story in order to draw larger crowds through the use of differing scenes began to formulate in the minds of early pioneers such as Georges Melies and Edwin S. -

American Scientist the Magazine of Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society

A reprint from American Scientist the magazine of Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society This reprint is provided for personal and noncommercial use. For any other use, please send a request to Permissions, American Scientist, P.O. Box 13975, Research Triangle Park, NC, 27709, U.S.A., or by electronic mail to [email protected]. ©Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society and other rightsholders Engineering Next Slide, Please Henry Petroski n the course of preparing lectures years—against strong opposition from Ibased on the material in my books As the Kodak some in the artistic community—that and columns, I developed during the simple projection devices were used by closing decades of the 20th century a the masters to trace in near exactness good-sized library of 35-millimeter Carousel begins its intricate images, including portraits, that slides. These show structures large and the free hand could not do with fidelity. small, ranging from bridges and build- slide into history, ings to pencils and paperclips. As re- The Magic Lantern cently as about five years ago, when I it joins a series of The most immediate antecedent of the indicated to a host that I would need modern slide projector was the magic the use of a projector during a talk, just previous devices used lantern, a device that might be thought about everyone understood that to mean of as a camera obscura in reverse. Instead a Kodak 35-mm slide projector (or its to add images to talks of squeezing a life-size image through a equivalent), and just about every venue pinhole to produce an inverted minia- had one readily available. -

Lecture 4A: Cameras

CS6670: Computer Vision Noah Snavely Lecture 4a: Cameras Source: S. Lazebnik Reading • Szeliski chapter 2.2.3, 2.3 Image formation • Let’s design a camera – Idea 1: put a piece of film in front of an object – Do we get a reasonable image? Pinhole camera • Add a barrier to block off most of the rays – This reduces blurring – The opening known as the aperture – How does this transform the image? Camera Obscura • Basic principle known to Mozi (470‐390 BC), Aristotle (384‐322 BC) • Drawing aid for artists: described by Leonardo da Vinci (1452‐1519) Gemma Frisius, 1558 Source: A. Efros Camera Obscura Home‐made pinhole camera Why so blurry? Slide by A. Efros http://www.debevec.org/Pinhole/ Shrinking the aperture • Why not make the aperture as small as possible? • Less light gets through • Diffraction effects... Shrinking the aperture Adding a lens “circle of confusion” • A lens focuses light onto the film – There is a specific distance at which objects are “in focus” • other points project to a “circle of confusion” in the image – Changing the shape of the lens changes this distance Lenses F focal point • A lens focuses parallel rays onto a single focal point – focal point at a distance f beyond the plane of the lens (the focal length) • f is a function of the shape and index of refraction of the lens – Aperture restricts the range of rays • aperture may be on either side of the lens – Lenses are typically spherical (easier to produce) Thin lenses • Thin lens equation: – Any object point satisfying this equation is in focus – What is the shape -

Device-Independent Representation of Photometric Properties of a Camera

CVPR CVPR #**** #**** CVPR 2010 Submission #****. CONFIDENTIAL REVIEW COPY. DO NOT DISTRIBUTE. 000 054 001 055 002 056 003 Device-Independent Representation of Photometric Properties of a Camera 057 004 058 005 059 006 Anonymous CVPR submission 060 007 061 008 062 009 Paper ID **** 063 010 064 011 065 012 Abstract era change smoothly across different device configurations. 066 013 The primary advantages of this representation are the fol- 067 014 In this paper we propose a compact device-independent lowing: (a) generation of an accurate representation using 068 015 representation of the photometric properties of a camera, the measured photometric properties at a few device config- 069 016 especially the vignetting effect. This representation can urations obtained by sparsely sampling the device settings 070 017 be computed by recovering the photometric parameters at space; (b) accurate prediction of the photometric parame- 071 018 sparsely sampled device configurations(defined by aper- ters from this representation at unsampled device configu- 072 019 ture, focal length and so on). More importantly, this can rations. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first 073 020 then be used for accurate prediction of the photometric device independent representation of photometric proper- 074 021 parameters at other new device configurations where they ties of cameras which has the capability of predicting device 075 022 have not been measured. parameters at configurations where it was not measured. 076 023 Our device independent representation opens up the op- 077 024 portunity of factory calibration of the camera and the data 078 025 1. Introduction then being stored in the camera itself. -

Single-Image Vignetting Correction Using Radial Gradient Symmetry

Single-Image Vignetting Correction Using Radial Gradient Symmetry Yuanjie Zheng1 Jingyi Yu1 Sing Bing Kang2 Stephen Lin3 Chandra Kambhamettu1 1 University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA {zheng,yu,chandra}@eecis.udel.edu 2 Microsoft Research, Redmond, WA, USA [email protected] 3 Microsoft Research Asia, Beijing, P.R. China [email protected] Abstract lenge is to differentiate the global intensity variation of vi- gnetting from those caused by local texture and lighting. In this paper, we present a novel single-image vignetting Zheng et al.[25] treat intensity variation caused by texture method based on the symmetric distribution of the radial as “noise”; as such, they require some form of robust outlier gradient (RG). The radial gradient is the image gradient rejection in fitting the vignetting function. They also require along the radial direction with respect to the image center. segmentation and must explicitly account for local shading. We show that the RG distribution for natural images with- All these are susceptible to errors. out vignetting is generally symmetric. However, this dis- We are also interested in vignetting correction using a tribution is skewed by vignetting. We develop two variants single image. Our proposed approach is fundamentally dif- of this technique, both of which remove vignetting by min- ferent from Zheng et al.’s—we rely on the property of sym- imizing asymmetry of the RG distribution. Compared with metry of the radial gradient distribution. (By radial gradient, prior approaches to single-image vignetting correction, our we mean the gradient along the radial direction with respect method does not require segmentation and the results are to the image center.) We show that the radial gradient dis- generally better. -

Photographic Printing Enlarger

Photographic printing From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Photographic printing is the process of producing a final image on paper for viewing, using chemically sensitized paper. The paper is exposed to a photographic negative, a positive transparency (or slide), or a digital image file projected using an enlarger or digital exposure unit such as a LightJet printer. Alternatively, the negative or transparency may be placed atop the paper and directly exposed, creating a contact print. Photographs are more commonly printed on plain paper, for example by a color printer, but this is not considered "photographic printing". Following exposure, the paper is processed to reveal and make permanent the latent image. Printing on black-and-white paper The process consists of four major steps, performed in a photographic darkroom or within an automated photo printing machine. These steps are: Exposure of the image onto the sensitized paper using a contact printer or enlarger; Processing of the latent image using the following chemical process: o Development of the exposed image reduces the silver halide in the latent image to metallic silver; o Stopping development by neutralising, diluting or removing the developing chemicals; o Fixing the image by dissolving undeveloped silver halide from the light-sensitive emulsion: o Washing thoroughly to remove processing chemicals protects the finished print from fading and deterioration. Optionally, after fixing, the print is treated with a hypo clearing agent to ensure complete removal of the fixer, which would otherwise compromise the long term stability of the image. Prints can be chemically toned or hand coloured after processing.[ Enlarger From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia An enlarger is a specialized transparency projector used to produce photographic prints from film or glass negatives using the gelatin silver process, or from transparencies. -

Dr. Kevin Grazier

Carl Sagan Center for Earth and Space Science Education Dr. Kevin Grazier Planetary Scientist NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Research Specialty: Large scale computational simulations of the Solar System Comfortable with the following age ranges: all Comfortable with the following audience sizes: all Dr. Kevin Grazier is a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). He did his doctoral research in planetary physics at UCLA, performing long-term large-scale computer simulations of early Solar System evolution. He started at JPL in 1995 as an academic part-time student, finishing his Ph.D. dissertation in 1997. At JPL, Dr. Grazier has written mission planning and analysis software that won JPL- and NASA-wide awards. He currently holds the duel titles of Investigation Scientist and Science Planning Engineer for the Cassini/Huygens Mission to Saturn and Titan. Dr. Grazier also continues research involving computer simulations of Solar System dynamics, evolution, and chaos with collaborators at UCLA, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Purdue University, and the University of Auckland. In addition to his JPL duties, Dr. Grazier teaches classes in basic astronomy, planetary science, cosmology, and the search for extraterrestrial life at UCLA and Santa Monica College. On a lighter note, Dr. Grazier also currently serves as the science advisor for the PBS educational animated series The Zula Patrol, and also for the SciFi Channel series Battlestar Galactica. Presentation Overviews and AV Requirements: Classroom Visits Our Solar System Grades K-6 What do the planets look like, and what makes each planet special? We examine each planet in the Solar System, and answer some of these questions. -

Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art Under the Spell of the Projected Image

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2007 PREPRINT 333 Wolfgang Lefèvre (ed.) Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I – INTRODUCING AN INSTRUMENT The Optical Camera Obscura I A Short Exposition Wolfgang Lefèvre 5 The Optical Camera Obscura II Images and Texts Collected and presented by Norma Wenczel 13 Projecting Nature in Early-Modern Europe Michael John Gorman 31 PART II – OPTICS Alhazen’s Optics in Europe: Some Notes on What It Said and What It Did Not Say Abdelhamid I. Sabra 53 Playing with Images in a Dark Room Kepler’s Ludi inside the Camera Obscura Sven Dupré 59 Images: Real and Virtual, Projected and Perceived, from Kepler to Dechales Alan E. Shapiro 75 “Res Aspectabilis Cujus Forma Luminis Beneficio per Foramen Transparet” – Simulachrum, Species, Forma, Imago: What was Transported by Light through the Pinhole? Isabelle Pantin 95 Clair & Distinct. Seventeenth-Century Conceptualizations of the Quality of Images Fokko Jan Dijksterhuis 105 PART III – LENSES AND MIRRORS The Optical Quality of Seventeenth-Century Lenses Giuseppe Molesini 117 The Camera Obscura and the Availibility of Seventeenth Century Optics – Some Notes and an Account of a Test Tiemen Cocquyt 129 Comments on 17th-Century Lenses and Projection Klaus Staubermann 141 PART IV – PAINTING The Camera Obscura as a Model of a New Concept of Mimesis in Seventeenth-Century Painting Carsten Wirth 149 Painting Technique in the Seventeenth Century in Holland and the Possible Use of the Camera Obscura by Vermeer Karin Groen 195 Neutron-Autoradiography of two Paintings by Jan Vermeer in the Gemäldegalerie Berlin Claudia Laurenze-Landsberg 211 Gerrit Dou and the Concave Mirror Philip Steadman 227 Imitation, Optics and Photography Some Gross Hypotheses Martin Kemp 243 List of Contributors 265 PART I INTRODUCING AN INSTRUMENT Figure 1: ‘Woman with a pearl necklace’ by Vermeer van Delft (c.1664). -

The Stereoscopic Cinema: from Film to Digital Projection

TECHNICAL PAPER The Stereoscopic Cinema: From Film to Digital Projection By Lenny Lipton Lenny Lipton A noteworthy improvement in the projection of stereoscopic moving awaited the invention of commercial- images is taking place; the image is clear and easy to view. Moreover, the quality sheet polarizers by Edwin setup of projection is simplified, and requires no tweaking for continued Land, who applied the material to 3 performance at a high-quality level. The new system of projection relies stereoscopic eyewear. on the Texas Instruments Digital Micromirror Device (DMD), and the The Norling approach became the model for the theatrical motion pic- basis for this paper is the Christie Digital Mirage 5000 projector and ture stereoscopic boom of the early StereoGraphics selection devices, CrystalEyes and the ZScreen. 1950s. In those days theaters had two projectors in the booth for changeover from reel to reel, provid- tereoscopic cinema has not problems of the past to better appreci- ing an opportunity to modify the Sbecome an accepted part of the ate the virtues of the improvement setup to run interlocked left and right neighborhood theatrical experience described. projectors (Fig. 1). because the technology hasn’t been Polarization Efforts It may well be that problems in the perfected to the point where it is satis- projection booth bear the major share fying for either the exhibitor or the The first successful (and influential) of responsibility for this short-lived viewer. However, the medium has commercial use of full-color stereo- effort. Polaroid researchers Jones and become widely accepted in theme scopic movie projection in the U.S. -

Pinhole Projector

Pinhole Projector I just threw together this little camera obscura for fun. It demonstrates pin- hole optics well, and doesn't require film and developing, so it is very quick from build to demonstration. It might be useful for science education purposes? Other than a teaching tool it has little real purpose other than a fun diversion for a few minutes on a lazy weekend. You can replace the screen with a piece of film and add a shutter to take real pictures if you like, but you'll need to carefully seal all light leaks. In my implementation I used a small piece of Aluminium roof flashing for the pinhole plate. The hole was drilled carefully with the smallest needle that my girlfriend could find in her kit. The larger box was added after the the smaller box proved the concept, but also demonstrated the need for a light shield to give enough contrast to view even bright scenes. The projection screen is greased kitchen wrap paper. The pinhole is about 0.5 mm in diameter and the smaller box is a 100 mm cubic shape, so the effective lens f-number is 200. A fantastically slow lens compared to glass optics, but fairly fast for a pinhole camera. You can enlarge the hole further if you wish to improve the brightness, but the resolution will suffer. Although the image is quite dim, it is acceptable for average daylight scenes out a window. Throwing a piece of dark cloth over your head to seal light leaks around your face helps a lot. -

The Saturn System 1

GETTING TO KNOW SATURN LESSON The Saturn System 1 3 hrs Students learn the concept of a system and apply it to learning about the Saturn sys- tem. They work with a ready-made scale diagram of the Saturn system, including the planet, rings, and moons. MEETS NATIONAL The lesson prepares students to complete a SCIENCE EDUCATION STANDARDS: Venn diagram that compares and contrasts Unifying Concepts the Saturn and Earth–Moon systems in and Processes • Systems, order, terms of the systems’ components and and organization interactions. Composite of Voyager images of Saturn and some of the moons. Earth and Space Science PREREQUISITE SKILLS BACKGROUND INFORMATION • Earth in the Solar System Working in groups Background for Lesson Discussion, page 2 Drawing and interpreting system diagrams Questions, page 7 Measuring in millimeters Answers in Appendix 1, page 225 Computation (multiplication and division) 1–21: Saturn Completing a Venn diagram 22–34: Rings 35–50: Moons 51–55: Observing Saturn in the Sky EQUIPMENT, MATERIALS, AND TOOLS For the teacher Materials to reproduce Photocopier (for transparencies & copies) Figures 1–8 are provided at the end of Overhead projector this lesson. Chalkboard, whiteboard, or easel with FIGURE TRANSPARENCY COPIES paper; chalk or markers 1 1 1 per group Color image or video of Saturn (optional) 2 1 optional Basketball (optional) 3 1 per group For each group of 3 to 4 students 4 1 per group Chart paper (18" x 22"); color markers 5 1 per group Notebook paper; pencils; clear adhesive 6 1 per group tape; scissors; ruler with millimeter 7 optional divisions 8 1 per student Meter stick (optional) 1 Saturn Educator Guide • Cassini Program website — http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/cassini/educatorguide • EG-1999-12-008-JPL Background for Lesson Discussion LESSON • Moon–moon interactions include Epimetheus 1 Comparing the Saturn system to Earth’s system and Janus swapping orbits.