Prospects for Free Trade Agreements in East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

The Effects of ASEAN Free Trade Are to Its Members

Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 21, November 2006 Determinants of AFTA Members’ Trade Flows and Potential for Trade Diversion By Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong* *Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong are Research Assistant at the Department of Economics Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Teaching Assistant at the Faculty of Economics, University of Indonesia, The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CSIS, ARTNeT members, partners and the United Nations. This study was conducted as part of the Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) initiative, aimed at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The technical support of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific is gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors. The authors may be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected] The Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) aims at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. The ARTNeT Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about trade issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. ARTNeT working papers are available online at: www.artnetontrade.org. -

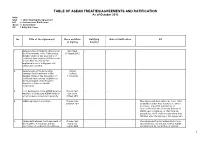

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Asian Ftas: Trends and Challenges

ADBI Working Paper Series Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges Masahiro Kawai and Ganeshan Wignaraja No. 144 August 2009 Asian Development Bank Institute Masahiro Kawai is dean of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) in Tokyo. Ganeshan Wignaraja is a principal economist in the Office of Regional and Economic Integration at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Manila. This paper was prepared as a chapter for a forthcoming book, Asian Regionalism in the World Economy: Engine for Dynamism and Stability, edited by Masahiro Kawai, Jong-Wha Lee, and Peter A. Petri. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Kawai, M., and G. Wignaraja. 2009. Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges. ADBI Working Paper 144. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working-paper/2009/08/04/3256.asian.fta.trends.challenges/ Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2009 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 144 Kawai and Wignaraja Abstract Although a latecomer, economically important Asia has emerged at the forefront of global free trade agreement (FTA) activity. -

Handbook on Preferential Market Access for Asean Least Developed Countries

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT HANDBOOK ON PREFERENTIAL MARKET ACCESS FOR ASEAN LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES Part III: ASEAN-FTA Agreements Layout and Printing at United Nations, Geneva – 2017833 (E) – March 2021 – 730 – UNCTAD/ALDC/2019/5 “Mazzarello - geometrie del dare, nuovo futuro” is the work of Maurizio Cancelli. Its architectural perspective emphasizes the interactions of governments, societies and economies from around the globe under the United Nations Framework. This collaboration highlights the earth, its resources and potentials, and fosters a recognition of local communities and their right to exist in their places of origin, with their own distinction and diversity. Maurizio Cancelli started his artistic research on the right to live in one’s place of birth more than thirty years ago. His work is inspired by the mountainous terrain surrounding the village of Cancelli in the heart of Umbria, Italy. UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT HANDBOOK ON PREFERENTIAL MARKET ACCESS FOR ASEAN LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES Part III: ASEAN-FTA Agreements Geneva, 2021 © 2021, United Nations This work is available through open access, by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

AFTA) on Labour and Employment: the Case of Indonesia

asean ILO/ASEAN Joint Study on Social Implications of ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) on Labour and Employment: The Case of Indonesia By Tirta Hidayat Diah Widarti Jakarta, December 2005 1 ILO/ASEAN Joint Study on “Social Implications of ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) on Labour and Employment: The Case of Indonesia” Copyright@International Labour Organization 2005 First published 2005 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; email: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; email: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO International Labour Organization, 2005 ILO/ASEAN Joint Study on “Social Implications of ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) on Labour and Employment: The Case of Indonesia” ISBN 92-2-117320-8 (print) 92-2-117321-6 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

The Impacts of AFTA on International Trade in Laos

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LOGISTICS AND TRADE 99 Volume 13, Number 1, April 2015, pp.99~121 The Impacts of AFTA on International Trade in Laos Outhai KEOCHAIYOM* _________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Laos joined ASEAN in 1997 and has practiced the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) scheme under ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) since 1998. To estimate the effects of AFTA on international trade in Laos, this paper has built a gravity model to analyze the specific effects of AFTA on aggregate international trade volume, import and export in Laos by using bilateral trade data between Laos and 29 partner countries during 2000 and 2012. Binary variables and the size of economy of AFTA are chosen to be the two variables reflecting the effect of AFTA on international trade of Laos. Results indicate that AFTA has positive effects on aggregate international trade volume and import while negative effects on export in Laos. Key Words: Laos;AFTA; international trade; gravity model. JEL Classification: F14, F15, R11 * School of Economics and Trade, Hunan University, Changsha 410079, China [email protected] 100 Outhai KEOCHAIYOM 1. Introduction Lao People’s Democratic Republic is one of the landlocked countries in Southeast Asian region with a population of over 6.5 million people in 2012 and a land area of 236.800 square kilometers , it shares the border with China to the north, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the south, Thailand to the west and Myanmar to the northwest. In 1975, the declaration of established Lao People’s Democratic Republic lead Laos to be governed under a socialist system and the state adopted a central planned economic system, centralizing investment, production, trade and pricing that created barriers to internal and foreign trade. -

Timor-Leste and ASEAN's Free Trade Agreements

TIMOR-LESTE AND ASEAN’S FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS Shona Hawkes, Researcher, La’o Hamutuk This is an English translation of an article that appeared in the Timor-Leste NGO Forum’s Bulletin, “Lian Fongtil,” June 2010. At the moment Timor-Leste is starting the process to become a member of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN is a regional group created in 1967. Its older members are Indonesia, The Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei. Newer members are Cambodia, Viet Nam, Laos and Myanmar/Burma. ASEAN tries to strengthen economic, military and social-cultural cooperation and links. Initially this cooperation was based only on goodwill. However since 2007 ASEAN has focused on creating sanction-based mechanisms to ensure that members follow ASEAN agreements. Timor-Leste hopes to enter ASEAN in 2012. The largest obligations for ASEAN members are its Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). FTAs are agreements between one or more nations or regions. This can include rules on import taxes, and affect laws about finances, agricultural and industrial policy and also open competition between the State and the private sector in providing public services such as health care, water, electricity and education. All ASEAN members except Laos are members of the World Trade Organization. If Timor- Leste becomes an ASEAN member it must also follow the 23 WTO agreements. These agreements require its 150+ members to follow one packet of rules. This limits governments’ ability to create policies and laws based on national needs. The WTO sistem does not recognize governments rights and responsibilities to ensure that everybody has a good quality of life. -

Taking Advantage of ASEAN's Free Trade Agreements

Taking Advantage of ASEAN’s Free Trade Agreements A GUIDE FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED ENTERPRISES By Paige McClanahan, Alexander Chandra, Ruben Hattari and Damon Vis-Dunbar January 2014 ASEAN BAC © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. About IISD The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) contributes to sustainable development by advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change and energy, and management of natural and social capital, as well as the enabling role of communication technologies in these areas. We report on international negotiations and disseminate knowledge gained through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries, better networks spanning the North and the South, and better global connections among researchers, practitioners, citizens and policy-makers. IISD’s vision is better living for all—sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live sustainably. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and from the Province of Manitoba. The Institute receives project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations and the private sector. HEAD OFFICE 161 Portage Avenue East, 6th Floor, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 0Y4 Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 | Fax: +1 (204) 958-7710 | Website: www.iisd.org TAKING ADVANTAGE OF ASEAN’S FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS A guide for small and medium-sized enterprises Foreword The U.K. -

ASEAN Moves Toward Greater Regional Cooperation in the Face of the EC and NAFTA Deborah A

American University International Law Review Volume 9 | Issue 3 Article 4 1994 Out of Others' Shadows: ASEAN Moves Toward Greater Regional Cooperation in the Face of the EC and NAFTA Deborah A. Haas Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Haas, Deborah A. "Out of Others' Shadows: ASEAN Moves Toward Greater Regional Cooperation in the Face of the EC and NAFTA." American University International Law Review 9, no. 3 (1994): 809-867. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OUT OF OTHERS' SHADOWS: ASEAN MOVES TOWARD GREATER REGIONAL COOPERATION IN THE FACE OF THE EC AND NAFTA Deborah A. Haas* INTRODUCTION In January 1992, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN or Association) pledged to strengthen economic, political, and security ties among its members.' To achieve these goals, the ministers proposed the creation of an ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA).2 ASEAN's so-called "mini dragons,"' feeling threatened by potential protectionist * J.D., 1994, Washington College of Law, The American University. 1. ASEAN is the acronym for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations Declaration (Bangkok Declaration), Aug. 8, 1967, Indon.-Malay.-PhiU.-Sing.-Thail., reprinted in 6 I.L.M. -

ASEAN Free Trade Agreement: a Major Mile Stone in the 50 Years of ASEAN

ESSAYS: MiniSTERS AND SENIOR OFFICIALS ASEAN Free Trade Agreement: A Major Mile stone in the 50 Years of ASEAN Narongchai Akrasanee In its 50 years of existence, ASEAN has had a number of milestones. Its decision to adopt the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA) in January 1992 was a major milestone that ASEAN reached, after which the process of ASEAN’s becoming a community was accelerated, and was reached in 2015. How ASEAN got to the AFTA milestone is the subject of this essay. ASEAN was set up in 1967 mainly for political reasons. It was meant to be an institution to prevent communism from spreading to Southeast Asia. Economic cooperation was minimal at first. 149 At the end of the Viet Nam War in April 1975, with the Socialist North Vietnam having won the war, the ASEAN-5 held a summit in Bali, Indonesia, in 1976, followed by another summit in 1977 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. At these summits, economic cooperation schemes were highlighted, as ASEAN was expected to be more unified by stronger integrated economies. The Preferential Trading Arrangements and the ASEAN Industrial Projects were two of the schemes adopted. But not much came out of these schemes after 1977. Then the oil crisis hit the world in 1979, with most economies adversely affected by the high oil prices, particularly the United States (US) as it was the world’s biggest importer of oil at that time. Most countries, including in ASEAN, experienced slow growth in the early 1980s. Drastic changes happened in the world economy, culminating in the major realignment of exchange rates – particularly between the US dollar and the Japanese yen and German mark – in what is known as the Plaza Accord of September 1985. -

The Status of East Asian Free Trade Agreements

ADBI Working Paper Series The Status of East Asian Free Trade Agreements Yunling Zhang and Minghui Shen No. 282 May 2011 Asian Development Bank Institute Yunling Zhang is professor at and director of the Academic Division of International Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). Minghui Shen is associate research fellow at the Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, CASS. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent, or the views of the IDB or its member countries, ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Zhang, Y., and M. Shen. 2011. The Status of East Asian Free Trade Agreements. ADBI Working Paper 282. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2011/05/17/4534.status.east.asian.free.trade.agreements/ Please contact the author(s) for information about this paper.