ASEAN Moves Toward Greater Regional Cooperation in the Face of the EC and NAFTA Deborah A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

The Effects of ASEAN Free Trade Are to Its Members

Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade Working Paper Series, No. 21, November 2006 Determinants of AFTA Members’ Trade Flows and Potential for Trade Diversion By Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong* *Indira M. Hapsari and Carlos Mangunsong are Research Assistant at the Department of Economics Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and Teaching Assistant at the Faculty of Economics, University of Indonesia, The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CSIS, ARTNeT members, partners and the United Nations. This study was conducted as part of the Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) initiative, aimed at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. This work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada. The technical support of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific is gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors. The authors may be contacted at [email protected] and [email protected] The Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) aims at building regional trade policy and facilitation research capacity in developing countries. The ARTNeT Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about trade issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. ARTNeT working papers are available online at: www.artnetontrade.org. -

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

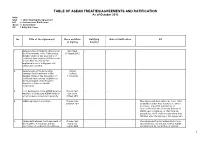

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Title Items-In-Visits of Heads of States and Foreign Ministers

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 15/06/2006 Time 4:59:15PM S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Title items-in-Visits of heads of states and foreign ministers Date Created 17/03/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0907-0001: Correspondence with heads-of-state 1965-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit •3 felt^ri ly^f i ent of Public Information ^ & & <3 fciiW^ § ^ %•:£ « Pres™ s Sectio^ n United Nations, New York Note Ko. <3248/Rev.3 25 September 1981 KOTE TO CORRESPONDENTS HEADS OF STATE OR GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERS TO ATTEND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION The Secretariat has been officially informed so far that the Heads of State or Government of 12 countries, 10 Deputy Prime Ministers or Vice- Presidents, 124 Ministers for Foreign Affairs and five other Ministers will be present during the thirty-sixth regular session of the General Assembly. Changes, deletions and additions will be available in subsequent revisions of this release. Heads of State or Government George C, Price, Prime Minister of Belize Mary E. Charles, Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and External Affairs of Dominica Jose Napoleon Duarte, President of El Salvador Ptolemy A. Reid, Prime Minister of Guyana Daniel T. arap fcoi, President of Kenya Mcussa Traore, President of Mali Eeewcosagur Ramgoolare, Prime Minister of Haur itius Seyni Kountche, President of the Higer Aristides Royo, President of Panama Prem Tinsulancnda, Prime Minister of Thailand Walter Hadye Lini, Prime Minister and Kinister for Foreign Affairs of Vanuatu Luis Herrera Campins, President of Venezuela (more) For information media — not an official record Office of Public Information Press Section United Nations, New York Note Ho. -

SWUTC/09/167861-1 the US-Brazil-China Trade and Transportation Triangle

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. SWUTC/09/167861-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date March 2009 The U.S.-Brazil-China Trade and Transportation Triangle: 6. Performing Organization Code Implications for the Southwest Region 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Dr. Leigh B. Boske and John C. Cuttino Report 167861 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Transportation Research University of Texas at Austin 11. Contract or Grant No. 3208 Red River, Suite 200 10727 Austin, Texas 78705-2650 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Southwest Region University Transportation Center Texas Transportation Institute Texas A&M University System 14. Sponsoring Agency Code College Station, Texas 77843-3135 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by general revenues from the State of Texas. 16. Abstract The advent of globalization and more integrated international trade has placed increased demands on transportation infrastructure. This report assesses the impacts of triangular trade between and among the United States, Brazil and China with an emphasis on the effects on the U.S. Southwest region. Triangular trade is viewed through a trade corridor analysis of the three sets of bilateral trading relationships. Special emphasis is given to the transportation services that delimit the capacity to carry out triangular trade with particular attention to the latest developments in services and schedules. While international trade trend analysis may point to China’s explosive consumption of raw materials from the U.S. and Brazil, this report also signals the increasing Chinese presence in the U.S. -

The Dominican Republic's Trade, Policies, and Effects in Historical Perspective

Trading development or developing trade? The Dominican Republic’s trade, policies, and effects in historical perspective* LETICIA ARROYO ABAD Profesora asistente del Department of Economics and in the International Politics & Economics, Middlebury College (EEUU). Correo electrónico: [email protected]. La autora es Licenciada en Economía de la Universidad Católica Argentina. Magister en estudios latinoa- mericanos de la University Of Kansas (EEUU). Doctora en economía con especialización en historia económica latinoamericana de la University of California, Davis (EEUU). Entre sus publicaciones tenemos: “Persistent Inequality? Trade, Factor Endowments, and Inequality in Republi- can Latin America”Journal of Economic History 73-1 (2012); y “Between Conquest and Independence: Living Standards in Spanish Latin America”, Explorations in Economic History, 49-2 (2012). Entre sus intereses se encuentran los temas de historia económica latinoamericana, los estudios sobre los estándares de vida, desigualdad e instituciones. AMELIA U. SANTOS-PAULINO Afiliada institucionalmente a la United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Suiza). Correo electrónico: [email protected]. La autora es Licenciada en Eco- nomía de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra (República Dominicana) y Doctora en Economía de la University of Kent (Reino Unido). Tenemos entre sus publi- caciones recientes: “Can Free Trade Agreements Reduce Economic Vulnerability?,” South African Journal of Economics Vol. 74, 4 (2011) y “The Dominican Republic Trade Policy Review 2008,” The World Economy Vol. 33,11 (2010). Sus líneas de investigación son: comercio exterior y desarrollo económico. Recibido: 30 de noviembre de 2012 Aprobado: 03 de abril de 2013 Modificado: 15 de mayo de 2013 Artículo de investigación científica * El presente artículo es resultado del proyecto de investigación “Long-term economic growth and 209 development”; financiada por la Foundation and the American Philosophical Society, (EEUU). -

The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 6 The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Thai and U.S. Army Soldiers participate in Cobra Gold 2006, a combined annual joint training exercise involving the United States, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. Photo by Efren Lopez, U.S. Air Force The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics By Zachary Abuza Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 Series Editors: C. Nicholas Rostow and Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

Asian Ftas: Trends and Challenges

ADBI Working Paper Series Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges Masahiro Kawai and Ganeshan Wignaraja No. 144 August 2009 Asian Development Bank Institute Masahiro Kawai is dean of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) in Tokyo. Ganeshan Wignaraja is a principal economist in the Office of Regional and Economic Integration at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Manila. This paper was prepared as a chapter for a forthcoming book, Asian Regionalism in the World Economy: Engine for Dynamism and Stability, edited by Masahiro Kawai, Jong-Wha Lee, and Peter A. Petri. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Kawai, M., and G. Wignaraja. 2009. Asian FTAs: Trends and Challenges. ADBI Working Paper 144. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working-paper/2009/08/04/3256.asian.fta.trends.challenges/ Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan Tel: +81-3-3593-5500 Fax: +81-3-3593-5571 URL: www.adbi.org E-mail: [email protected] © 2009 Asian Development Bank Institute ADBI Working Paper 144 Kawai and Wignaraja Abstract Although a latecomer, economically important Asia has emerged at the forefront of global free trade agreement (FTA) activity. -

Balance Trade

SECTION 2 • CHAPTER 4 Balance trade In this Oct. 18, 2011 photo, crew members look on as containers are offloaded from the cargo ship Stadt Rotenburg at Port Everglades in Fort Lauderdale. AP PHOTO/WILFREDO LEE oods and services trade—exports plus imports—now account for nearly one-third of overall U.S. economic Gactivity,2 meaning trade’s importance to the economy has never been greater. The United States is the world’s largest exporter,3 with exports directly supporting an estimated 9.7 million jobs.4 At the same time, the United States is also the world’s largest importer, and herein lies the problem. Over the past 30 years, our trade balance has been shifting in the wrong direction—toward more imports than exports—and reached a $560 billion deficit in 2012.5 While imports can be a boon to U.S. economic ing also carry offsetting costs, including job productivity and American living standards, losses domestically. Second, in order to pay providing consumers and business with for the imports from abroad that exceed U.S. access to a larger variety of goods and ser- exports, the U.S. economy must balance this vices at lower costs than would otherwise be trade deficit by selling assets—stocks, bonds, the case, there is also a price to pay. and other assets such as companies and real estate—to overseas purchasers. Mounting trade deficits present two key problems for the U.S. economy. First, the Our trade imbalance has resulted from a economic benefits made possible by import- number of factors. -

Prospects for Free Trade Agreements in East Asia

Prospects for Free Trade Agreements in East Asia January 2003 Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) Copyright © JETRO 2003 All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph, photocopy, or any other means, nor stored in any information retrieval system, without the express written permission of the publishers. (For Distribution in the U.S.) This material is distributed by the U.S. offices of JETRO (Atlanta, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco) on behalf of the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), Tokyo, Japan. Additional information is available at the Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. Introduction Since the start of the 1990s moves toward economic integration have progressed rapidly around the world, particularly in the form of free trade agreements. Within Asia, the ASEAN Free Trade Area was initiated by the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 1993 and has since reached its final formative stage, and in January 2002 Japan entered into its first bilateral free trade agreement, the Japan-Singapore Economic Partnership Agreement, which went into effect in November 2002. In November 2002 ASEAN and China concluded an agreement concerning comprehensive economic cooperation, including a commitment to work toward establishing an FTA. In addition, Japan and ASEAN have agreed to aim for the creation of JACEP, a Japan-ASEAN Closer Economic Partnership, as soon as possible within the next 10 years; government-level negotiations toward this end are to start in 2003. Meanwhile, countries including Australia, Singapore, and Thailand are actively seeking to conclude new bilateral FTAs. -

Thai-Chinese Relations: Security and Strategic Partnership

No. 155 Thai-Chinese Relations: Security and Strategic Partnership Chulacheeb Chinwanno S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 24 March 2008 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. RSIS’s mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: • Provide a rigorous professional graduate education in international affairs with a strong practical and area emphasis • Conduct policy-relevant research in national security, defence and strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations • Collaborate with like-minded schools of international affairs to form a global network of excellence Graduate Training in International Affairs RSIS offers an exacting graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The teaching programme consists of the Master of Science (MSc) degrees in Strategic Studies, International Relations, International Political Economy, and Asian Studies as well as an MBA in International Studies taught jointly with the Nanyang Business School. The graduate teaching is distinguished by their focus on the Asia Pacific, the professional practice of international affairs, and the cultivation of academic depth. Over 150 students, the majority from abroad, are enrolled with the School. A small and select Ph.D. programme caters to advanced students whose interests match those of specific faculty members. -

U.S. Protectionism and Trade Imbalance Between the U.S. and Northeast Asian Countries1

INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS RESEARCH JOURNAL. Vol. 13. No 2 (2018) U.S. Protectionism and Trade Imbalance between the U.S. and Northeast Asian Countries1 S.-C. Park Sang-Chul Park – Doctor, Professor, Graduate School of Knowledge Based Technology and Energy, Korea Polytechnic University; 2121, Jeongwang-Dong, Siheung-City, Gyeonggi-Do, 429-793, Korea; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Trade growth has slowed since the global financial crisis. In 2016, growth in the volume of world trade was 1.9%, down from the 2.8% increase registered in 2015. Imports to developed countries will be moderate in 2017, while demand for imported goods in developing Asian economies could continue to rise. Despite rising imports into Asia, the ratio of trade growth in the world has been lower than the ratio of global economic growth since 2013. Therefore, many countries have tried to create bilateral, multilateral, regional and mega free trade agreements (FTAs) in order to boost their trade volumes and economic growth. East Asian countries try to build regional FTAs and participate in different mega FTAs such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). As a result, their economic interests are rather deeply divided and are related to political and security issues in the East Asian context. At the same time, the protectionism led by the Trump administration in the U.S. stands in contrast to the approach taken by East Asian countries. This paper deals with this development and explores why the U.S. has turned from free and open trade toward so-called fair trade based on a policy of “America first.” It also offers an analysis of the reasons for trade imbalances between the U.S.