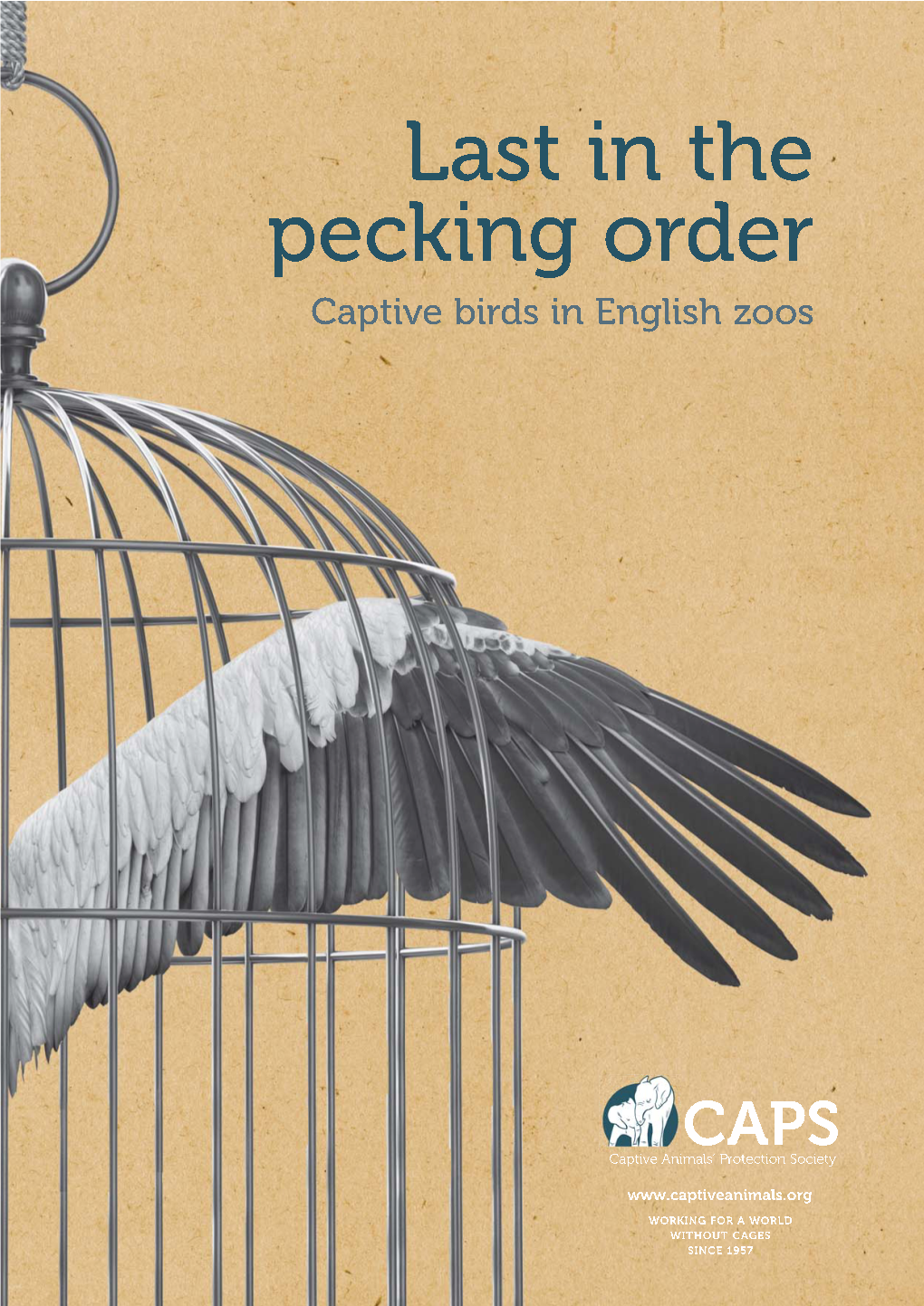

Last in the Pecking Order Captive Birds in English Zoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Watcher's General Store

BIRD OBSERVER BIRD OBSERVER ^4^ ■ ^ '- V - iIRDOBSEl jjjijdOBSEKSK fi« o , bs«s^2; bird observer ®^«D 0BS£, VOL. 21 NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 BIRD OBSERVER • s bimonthly {ournal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. VOL. 21, NO. 1 FEBRUARY 1993 Editor In Chief Corporate Officers Board of Directors Martha Steele President Dorothy R. Arvidson Associate Editor William E. Davis, Jr. Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer Herman H. D'Entremont Lee E. Taylor Department Heads H. Christian Floyd Clerk Cover Art Richard A. Forster Glenn d'Entremont William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry David E. Lange John C. Kricher Feature Articles and Advertisements David E. Lange Field Notes Robert H. Stymeist John C. Kricher Simon Perkins Book Reviews Associate Staff Wayne R. Petersen Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Marjorie W. Rines Bird Sightings Martha Vaughan John A. Shetterly Robert H. Stymeist Editor Emeritus Martha Steele At a Glance Dorothy R. Arvidson Robert H. Stymeist Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER {USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1993 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER; Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $16 for 6 issues, $30 for two years in the U. S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies ^ .0 0 . -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Assessing Bird Species Popularity with Culturomics

Familiarity breeds content: assessing bird species popularity with culturomics Ricardo A. Correia1,2, Paul R. Jepson2, Ana C. M. Malhado1 and Richard J. Ladle1,2 1 Institute of Biological and Health Sciences, Federal University of Alagoas, Maceio´, Alagoas, Brazil 2 School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Understanding public perceptions of biodiversity is essential to ensure continued support for conservation efforts. Despite this, insights remain scarce at broader spatial scales, mostly due to a lack of adequate methods for their assessment. The emergence of new technologies with global reach and high levels of participation provide exciting new opportunities to study the public visibility of biodiversity and the factors that drive it. Here, we use a measure of internet saliency to assess the national and international visibility of species within four taxa of Brazilian birds (toucans, hummingbirds, parrots and woodpeckers), and evaluate how much of this visibility can be explained by factors associated with familiarity, aesthetic appeal and conservation interest. Our results strongly indicate that familiarity (human population within the range of a species) is the most important factor driving internet saliency within Brazil, while aesthetic appeal (body size) best explains variation in international saliency. Endemism and conservation status of a species had small, but often negative, effects on either metric of internet saliency. While further studies are needed to evaluate the relationship between internet content and the cultural visibility of different species, our results strongly indicate that internet saliency can be considered as a broad proxy of cultural interest. Submitted 4 December 2015 Subjects Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Computational science, Coupled natural and human Accepted 2 February 2016 systems Published 25 February 2016 Keywords Birds, Public perception, Biodiversity, Culturalness, Internet salience, Culturomics, Corresponding author Conservation Ricardo A. -

Compendium of Avian Ecology

Compendium of Avian Ecology ZOL 360 Brian M. Napoletano All images taken from the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framlst/infocenter.html Taxonomic information based on the A.O.U. Check List of North American Birds, 7th Edition, 1998. Ecological Information obtained from multiple sources, including The Sibley Guide to Birds, Stokes Field Guide to Birds. Nest and other images scanned from the ZOL 360 Coursepack. Neither the images nor the information herein be copied or reproduced for commercial purposes without the prior consent of the original copyright holders. Full Species Names Common Loon Wood Duck Gaviiformes Anseriformes Gaviidae Anatidae Gavia immer Anatinae Anatini Horned Grebe Aix sponsa Podicipediformes Mallard Podicipedidae Anseriformes Podiceps auritus Anatidae Double-crested Cormorant Anatinae Pelecaniformes Anatini Phalacrocoracidae Anas platyrhynchos Phalacrocorax auritus Blue-Winged Teal Anseriformes Tundra Swan Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Anatini Cygnini Anas discors Cygnus columbianus Canvasback Anseriformes Snow Goose Anatidae Anseriformes Anatinae Anserinae Aythyini Anserini Aythya valisineria Chen caerulescens Common Goldeneye Canada Goose Anseriformes Anseriformes Anatidae Anserinae Anatinae Anserini Aythyini Branta canadensis Bucephala clangula Red-Breasted Merganser Caspian Tern Anseriformes Charadriiformes Anatidae Scolopaci Anatinae Laridae Aythyini Sterninae Mergus serrator Sterna caspia Hooded Merganser Anseriformes Black Tern Anatidae Charadriiformes Anatinae -

BLESS Bird Guide to Lois Hole Centennial Provincial Park

Bird Guide to Lois Hole Centennial Provincial Park, Alberta Big Lake Environment Support Society Credits Technical information Most of the information on bird species was reprinted with permission from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s website AllAboutBirds.org, some text came from Wikipedia, and some was modified for the Big Lake region of Alberta. Photographs Local photographers were approached for good quality images, and where good photographs were not available then freely available images from Wikipedia were used (see page 166 for individual photo credits). Funding City of St. Albert, Environmental Initiatives Grant Administration and Review Miles Constable Big Lake Environment Support Society Produced by Big Lake Environment Support Society P.O. Box 65053 St. Albert, Ab T8N 5Y3 www.bless.ab.ca For information contact [email protected] 2 Bird Guide to Lois Hole Centennial Provincial Park, Alberta 2016 3 Location of Lois Hole Centennial Provincial Park, Alberta Map courtesy of Google, Inc. There are a great many birds to be seen in Lois Hole Centennial Provincial Park as Big Lake has been designated an Important Bird Area. This Guide features the most commonly seen birds; however, it is not a complete guide to all birds that could be seen at Big Lake. If you are, or become, passionate about birds, we recommend a comprehensive guide to the birds of North America as there are many species that migrate through Big Lake, or that are expanding their range into this area for a variety of reasons. There are also simply those individuals that wander off course and end up in our area; those wonderful lost individuals that keep birders on their toes. -

May/June 2017

Vol 36, Number 3 May/June 2017 WAS Meeting IT’S BIRD FESTIVAL TIME IN NORTHERN UTAH and By Betty Evans The 19th Great Salt Lake Bird Festival will be held May 18-22, 2017. Happenings Utah has many great birders and birding spots. Last year, 202 bird species were seen during the Festival by about 3,000 participants. Most bird watchers attending the Festival are local; however, the Festival has attracted visitors from 18 different states and several foreign countries. The number of bird watching field trips has Tuesday, May 16, 2017 expanded from 6 to 66 over the past 18 years. Noah Stryker, Associate Editor of Birding magazine, the author of WAS Meeting 7:00 PM two well-regarded books about birds, and a regular contributor of photographs and articles to major magazines, is the keynote Troy Burgess, with the Wasatch speaker and guest for the Bird Festival this year. Stryker set a world Wigeons conservation group. He Big Year record in 2015 and his book about the experience will be is going to talk about their released in the fall of 2017. He has studied birds on six continents and works as a naturalist guide on cruises to Antarctica and successful wood duck box Norway’s Svalbard archipelago. His first book, Among Penguins, program. chronicles a field season working with penguins in Antarctica; and his second, The Thing with Feathers, celebrates the fascinating behaviors of birds and human parallels. He is based in Oregon, where his backyard has hosted more than 100 species of birds. Tuesday, June 20, 2017 Our Utah State Parks, sites for many field trips, are celebrating their WAS Meeting 7:00 PM 60th anniversary. -

Evolution of Long-Term Coloration Trends with Biochemically Unstable

Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on May 18, 2016 Evolution of long-term coloration trends rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org with biochemically unstable ingredients Dawn M. Higginson, Virginia Belloni†, Sarah N. Davis, Erin S. Morrison, John E. Andrews and Alexander V. Badyaev Research Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA DMH, 0000-0003-4665-5902; VB, 0000-0001-9807-1912; ESM, 0000-0002-4487-6915 Cite this article: Higginson DM, Belloni V, Davis SN, Morrison ES, Andrews JE, Badyaev AV. The evolutionarily persistent and widespread use of carotenoid pigments in 2016 Evolution of long-term coloration trends animal coloration contrasts with their biochemical instability. Consequently, with biochemically unstable ingredients. evolution of carotenoid-based displays should include mechanisms to Proc. R. Soc. B 283: 20160403. accommodate or limit pigment degradation. In birds, this could involve http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.0403 two strategies: (i) evolution of a moult immediately prior to the mating season, enabling the use of particularly fast-degrading carotenoids and (ii) evolution of the ability to stabilize dietary carotenoids through metabolic modification or association with feather keratins. Here, we examine evol- Received: 23 February 2016 utionary lability and transitions between the two strategies across 126 species of birds. We report that species that express mostly unmodified, Accepted: 21 April 2016 fast-degrading, carotenoids have pre-breeding moults, and a particularly short time between carotenoid deposition and the subsequent breeding season. Species that expressed mostly slow-degrading carotenoids in their plumage accomplished this through increased metabolic modification of Subject Areas: dietary carotenoids, and the selective expression of these slow-degrading evolution, ecology compounds. -

Black-Backed Woodpecker

Wyoming(Birding(Bonanza( ( Special(Mission(2013:( Black;backed(Woodpeckers( ! ! ! ( ( Information(Packet( ( >>(uwyo.edu/biodiversity/birding( ! ! ! ! Mission(coordinated(by:! Wyoming!Natural!Diversity!Database!(uwyo.edu/wyndd)! UW!Vertebrate!Collection!(uwyo.edu/biodiversity/vertebrate?museum)! UW!Biodiversity!Institute!(uwyo.edu/biodiversity)! ! Table(of(Contents( ! Wanted Poster . pg. 3 Introduction to the Mission . pg. 4 Photo Guides . pg. 5 Vicinity Map . pg. 6 Observation Form . pg. 7 Species Abstract . pg. 9 ! ! ! ! ! Remember to bird ethically! Follow the link to read the American Birding Association’s Code of Ethics: http://www.aba.org/about/ethics.html! ! ! Page 2! Wyoming Birding Bonanza Special Mission 2013 WANTED: Sightings of the Black-backed Woodpecker This bird species is sought after in the Laramie Peak area in central Wyoming. It has never been seen there before, but because of this species' keen ability to find recently-burned forests to call home, authorities suspect it will appear. This species is petitioned for protection under the Endangered Species Act – we need your help to search for these birds in the Laramie Peak area, and submit your observation data! Adult Male Adult Female Ideal Black-backed Woodpecker Habitat submit your data! Submit observations at ebird.org More information: uwyo.edu/biodiversity/birding Bird Photos courtesy of Glen Tepke (http://www.pbase.com/gtepke/profile) Habitat Photo courtesy of Michael Wickens UW Vertebrate Collection Wyoming Birding Bonanza Special Mission 2013: Black-backed Woodpeckers The Issue: Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) is a large woodpecker that is distributed across the boreal forests of North America. In Wyoming, the species is found in the northwestern corner of the state, and also in the Black Hills. -

Recovery Plan for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus Principalis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) I Recovery Plan for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) April, 2010 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Approved: Regional Director, Southeast Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: II Disclaimer Notice of Copyrighted Material Cover Illustration Credit: Recovery Plans delineate Permission to use copyrighted A male Ivory-billed Woodpecker reasonable actions that are illustrations and images in the at a nest hole. (Photo by Arthur believed to be required to final version of this recovery plan Allen, 1935/Copyright Cornell recover and/or protect listed has been granted by the copyright Lab of Ornithology.) species. Plans published by holders. These illustrations the U.S. Fish and Wildlife are not placed in the public Service (Service) are sometimes domain by their appearance prepared with the assistance herein. They cannot be copied or of recovery teams, contractors, otherwise reproduced, except in state agencies, and other affected their printed context within this and interested parties. Plans document, without the consent of are reviewed by the public and the copyright holder. submitted for additional peer review before the Service adopts Literature Citation Should Read them. Objectives will be attained as Follows: and any necessary funds made U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. available subject to budgetary 200x. Recovery Plan for the and other constraints affecting Ivory-billed Woodpecker the parties involved, as well as the (Campephilus principalis). need to address other priorities. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Recovery plans do not obligate Atlanta, Georgia. -

An Overlooked Hotspot for Birds in the Atlantic Forest

ARTICLE An overlooked hotspot for birds in the Atlantic Forest Vagner Cavarzere¹; Ciro Albano²; Vinicius Rodrigues Tonetti³; José Fernando Pacheco⁴; Bret M. Whitney⁵ & Luís Fábio Silveira⁶ ¹ Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (UTFPR). Santa Helena, PR, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0510-4557. E-mail: [email protected] ² Brazil Birding Experts. Fortaleza, CE, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] ³ Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Ecologia. Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2263-5608. E-mail: [email protected] ⁴ Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO). Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2399-7662. E-mail: [email protected] ⁵ Louisiana State University, Museum of Natural Science. Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Estados Unidos. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8442-9370. E-mail: [email protected] ⁶ Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Museu de Zoologia (MZUSP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2576-7657. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Montane and submontane forest patches in the state of Bahia, Brazil, are among the few large and preserved Atlantic Forests remnants. They are strongholds of an almost complete elevational gradient, which harbor both lowland and highland bird taxa. Despite being considered a biodiversity hotspot, few ornithologists have surveyed these forests, especially along elevational gradients. Here we compile bird records acquired from systematic surveys and random observations carried out since the 1980s in a 7,500 ha private protected area: Serra Bonita private reserve. We recorded 368 species, of which 143 are Atlantic Forest endemic taxa. -

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club Volume 133 No. 3 September 2013 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS See also BOC website: http://www.boc-online.org BOC MEETINGS are open to all, not just BOC members, and are free. Evening meetings are held in an upstairs room at The Barley Mow, 104, Horseferry Road, Westminster, London SW1P 2EE. The nearest Tube stations are Victoria and St James’s Park; and the 507 bus, which runs from Victoria to Waterloo, stops nearby. For maps, see http://www.markettaverns.co.uk/the_barley_mow. html or ask the Chairman for directions. The cash bar will open at 6.00 pm and those who wish to eat after the meeting can place an order. The talk will start at 6.30 pm and, with questions, will last about one hour. It would be very helpful if those who are intending to come would notify the Chairman no later than the day before the meeting and preferably earlier. 24 September 2013—6.30 pm—Dr Roger Saford—Recent advances in the knowledge of Malagasy region birds Abstract: The Malagasy region comprises Madagascar, the Seychelles, the Comoros and the Mascarenes (Mauritius, Reunion and Rodrigues), six more isolated islands or small archipelagos, and associated sea areas. It contains one of the most extraordinary and distinctive concentrations of biological diversity in the world. The last 20 years have seen a very large increase in the level of knowledge of, and interest in, the birds of the region. This talk will draw on research carried out during the preparation of the first thorough handbook to the region’s birds—487 species—to be compiled since the late 19th century.