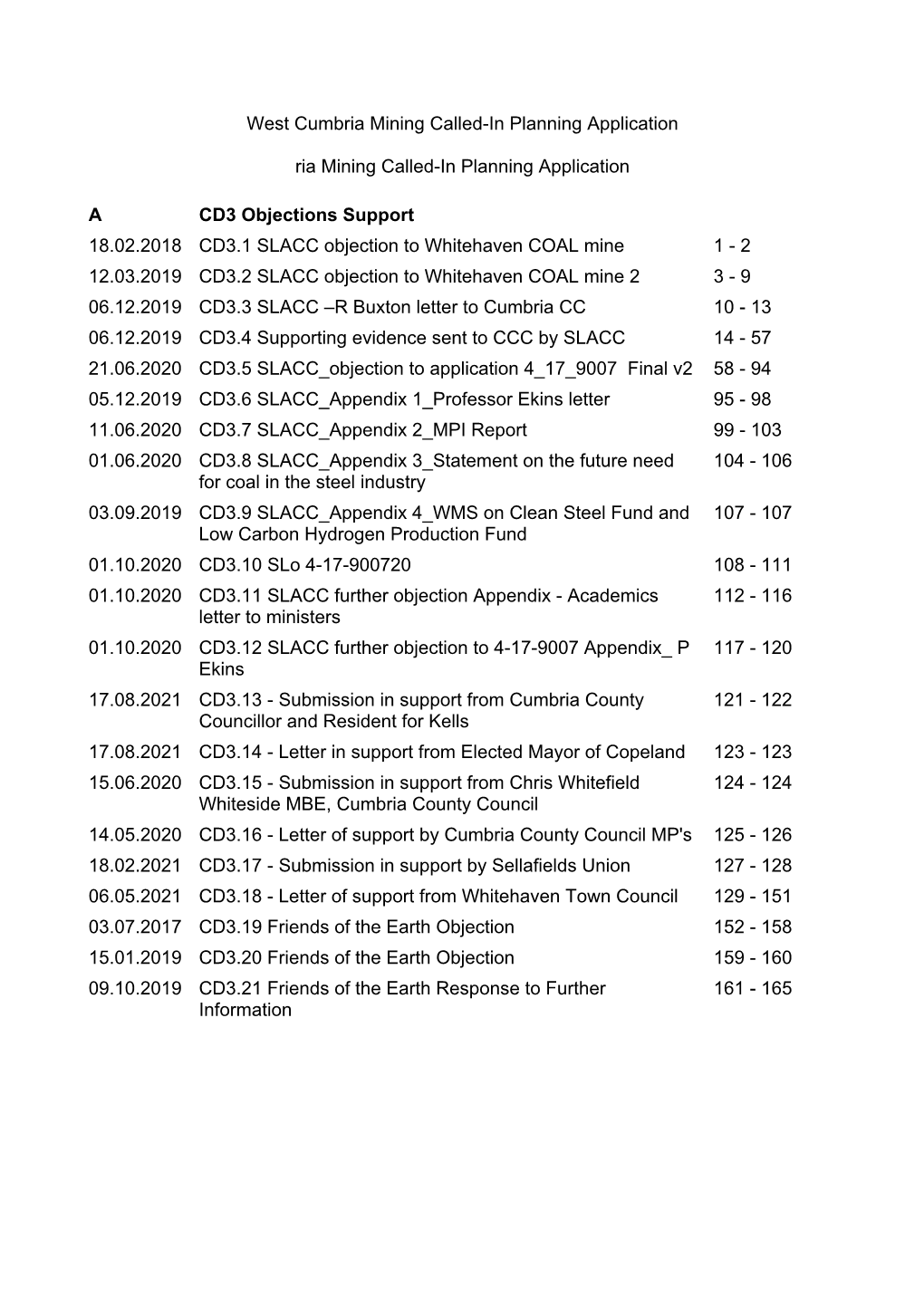

CD3 Objections Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name Club Men Michael Hutchinson In-Gear

Category (Ages) Name Club Men Michael Hutchinson In-Gear Quickvit RT Bradley Wiggins Garmin Slipstream Ian Stannard ISD - Neri Chris Newton Rapha Condor Rob Hayles Halfords/Bikehut Nino Piccoli API Metrow/Silverhook Mark Holton Shorter Rochford RT/Exclusive Wouter Sybrandy Team Sigma Sport Matthew Bottrill I-Ride RT/MG Décor Jez Cox Team Bike & Run/Maximuscle Colin Robertson Equipe Velo Ecosse Phill Sykes VC St Raphael/Waite Contracts Gyles Wingate Bognor Regis CC Matt Clinton Mike Vaughan Cycles Ben Price Finchley Racing Team Jesse Elzinga Beeline Bicycles RT Thomas Weatherall Oxford University CC Michael Nicolson Dooleys RT David Mclean La Poste/Rent a Car Graeme Hatcher Manx Viking Wheelers-Shoprite Duncan Urquhart Endura Racing/Pedalpower Jerone Walters Team Sigma Sport Adam Hardy Wolds RT Ian Taylor NFM Racing Team Andy Hudson Cambridge CC Michael Bannister Bedfordshire RCC Daniel Patten Magnus Maximus Coffee.com Thomas Collier Pendragon Kalas Peter Wood Sheffrec CC Ben Williams New Brighton CC David Clarke Pendragon Kalas Sebastian Ader …a3rg/PB Science/SIS John Tuckett AW Cycles/Giant Dominic Sweeney Lutterworth Cycle Centre Tejvan Pettinger SRI Chinmoy Cycling Team Charles McCulloch Shorter Rochford RT/Exclusive Anton Blackie Oxford University CC James Smith Somerset RC Lee Tunnicliffe Fit-Four/Cycles Dauphin James Schofield Oxford University Tri Club Simon Gaywood Team Corley/Cervelo Robin Ovenden Caesarean CC Gordon Leicester Rondelli/Horton Blake Pond Southfork Racing.co.uk Andrew Porter Welwyn Wheelers Arthur Doyle Dooleys -

Department of State Key Officers List

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 1/17/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan RSO Jan Hiemstra AID Catherine Johnson CLO Kimberly Augsburger KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ECON Jeffrey Bowan Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: EEO Erica Hall kabul.usembassy.gov FMO David Hilburg IMO Meredith Hiemstra Officer Name IPO Terrence Andrews DCM OMS vacant ISO Darrin Erwin AMB OMS Alma Pratt ISSO Darrin Erwin Co-CLO Hope Williams DCM/CHG Dennis W. Hearne FM Paul Schaefer Algeria HRO Dawn Scott INL John McNamara ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- MGT Robert Needham 2000, Fax +213 (21) 60-7335, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, MLO/ODC COL John Beattie Website: http://algiers.usembassy.gov POL/MIL John C. Taylor Officer Name SDO/DATT COL Christian Griggs DCM OMS Sharon Rogers, TDY TREAS Tazeem Pasha AMB OMS Carolyn Murphy US REP OMS Jennifer Clemente Co-CLO Julie Baldwin AMB P. Michael McKinley FCS Nathan Seifert CG Jeffrey Lodinsky FM James Alden DCM vacant HRO Dana Al-Ebrahim PAO Terry Davidson ICITAP Darrel Hart GSO William McClure MGT Kim D'Auria-Vazira RSO Carlos Matus MLO/ODC MAJ Steve Alverson AFSA Pending OPDAT Robert Huie AID Herbie Smith POL/ECON Junaid Jay Munir CLO Anita Kainth POL/MIL Eric Plues DEA Craig M. -

Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council Held on 3 December 2008

Manchester City Council Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council held on 3 rd December 2008 Present: The Right Worshipful, The Lord Mayor Councillor Mavis Smitheman – In the Chair Councillors Amesbury, Andrews, Ankers Ashley, J. Battle, Bethell, Bhatti, Boyes, Bracegirdle, Burns, Cameron, Carmody, Chohan, Chowdhury, Clayton, Commons, Cooley, Cooper, Cowan, Cowell, Cox, Curley, Dobson, Donaldson, Eakins, Evans, Fairweather, Fender, Fisher, Firth, Flanagan, Glover, Grant, Hackett, Harrison, Hassan, Helsby, Isherwood, Jones, Judge, Karney, Keegan, Keller, A. Khan, M. Khan, Kirkpatrick, Leese, Lewis, Lomax, Longsden, Loughman, Lyons, McCulley, M. Murphy, N. Murphy, P. Murphy, S. Murphy, E. Newman S. Newman, O’Callaghan, O’Connor, Barbara O'Neil, Brian O’Neil, Pagel, Parkinson, Pearcey, Priest, Pritchard, Rahman, Ramsbottom, Risby, Royle, Ryan, Sandiford, Shaw, Siddiqi, Smith, Stevens, Swannick, Trotman, Walters, Watson and Whitmore. Also Present: Honorary Aldermen Audrey Jones and John Smith. CC/08/82 Death of Councillor Neil Trafford The Lord Mayor formally recorded the sudden and tragic death of Councillor Neil Trafford as a result of a road traffic accident on Sunday 23 rd November. The Council recalled that Neil had served as Liberal Democrat Councillor for the Barlow Moor and Didsbury West Wards since 2003. He was an active Committee member and an acccomplished political campaigner across the North West of England. The Lord Mayor said that the generous tributes paid to him in public forums and numerous websites in recent days was perhaps the clearest testimony to the very high regard in which he was held in many different fields of activity. In a short life she said that he had clearly achieved much and members were left to wonder what more he might have contributed in the future. -

Track World Championships Men's Kilometer Time Trial 1981: Brno

Track World Championships 2. Shane Kelly (AUS) 2. Michelle Ferris (AUS) 3. Jens Gluecklich (GER) 3. Magali Marie Faure Men’s Kilometer Time Trial (FRA) 1981: Brno, Czechoslovakia 1994: Palermo, Italy 15. Nicole Reinhart (USA) 1. Lothar Thoms (GDR) 1. Florian Rousseau 2. Fredy Schmidtke (FRA) 1998: Bordeaux, France (FRG) 2. Erin Hartwell (USA) 1. Felicia Ballanger (FRA) 3. Sergei Kopylov (USSR) 3. Shane Kelly (AUS) 2. Tanya Dubincoff (CAN) 9. Brent Emery (USA) 3. Michelle Ferris (AUS) 1995: Bogota, Colombia 4. Chris Witty (USA) 1982: Leicester, England 1. Shane Kelly (AUS) 12. Nicole Reinhart (USA) 1. Fredy Schmidtke 2. Florian Rousseau (FRG) (FRA) 1999: Berlin, Germany 2. Lothar Thoms (GDR) 3. Erin Hartwell (USA) 1. Felicia Ballanger (FRA) 3. Emmanuel Raasch 2. Cuihua Jiang (CHN) (GDR) 1996: Manchester, England 3. Ulrike Weichelt (GER) 1. Shane Kelly (AUS) 16. Jennie Reed (USA) 1983: Altenrhein, Switzerland 2. Soren Lausberg (GER) 1. Sergei Kopylov (USSR) 3. Jan Van Eijden (GER) 2000: Manchester, Great 2. Gerhard Scheller Britain (FRG) 1997: Perth, Australia 1. Natalia Markovnichenko 3. Lothar Thoms (GDR) 1. Shane Kelly (AUS) (BLR) 15. Mark Whitehead 2. Soren Lausberg (GER) 2. Cuihua Jiang (CHN) (USA) 3. Stefan Nimke (GER) 3. Yan Wang (CHN) 9. Sky Christopherson 11. Tanya Lindenmuth 1985: Bassano del Grappa, (USA) Italy 2001: Antwerpen, Belgium 1. Jens Glucklich (GDR) 1998: Bordeaux, France 1. Nancy Reyes 2. Phillippe Boyer (FRA) 1. Andranu Tourant (FRA) Contreras (MEX) 3. Martin Vinnicombe 2. Shane Kelly (AUS) 2. Lori-Ann Muenzer (AUS) 3. Erin Hartwell (GER) (CAN) 3. Katrin Meinke (GER) 1986: Colorado Springs, Colo. -

2016 Olympic Cycling Media Guide

ROAD TRACK BMX MOUNTAIN BIKE AUGUST 6 - 10 AUGUST 11 - 16 AUGUST 17 - 19 AUGUST 20 - 21 2016 USA CYCLING OLYMPIC MEDIA GUIDE USA CYCLING ROAD EVENTS About the Road Race All riders start together and must complete a course of 241.5km (men) or 141km (women). The first rider to cross the finish line wins. About the Time Trial In a race against the clock, riders leave the start ramp individually, at intervals of 90 seconds, and complete a course of 54.5km (men) or 29.8km (women). The rider who records the fastest time claims gold. Team USA Olympic Road Schedule (all times local) Saturday, August 6 9:30 a.m. - 3:57 p.m. Men’s road race Fort Copacabana Sunday, August 7 12:15 - 4:21 p.m. Women’s road race Fort Copacabana Wednesday, August 10 8:30 - 9:46 a.m. Women’s individual time trial Pontal 10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m. Men’s individual time trial Pontal BACK TO THE TOP 2 2016 USA CYCLING OLYMPIC MEDIA GUIDE USA CYCLING ROAD 2016 OLYMPIC WOMEN’S TEAM BIOS POINTS OF INTEREST/PERSONAL Competed as a swimmer at Whtiman College Three-time collegiate national champion Works as a yoga instructor off the bike Serves on the City of Boulder’s Environmental Advisory Board OLYMPIC/WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP RESULTS 2014 UCI Road World Championships, Ponferrada, Spain — DNF road race 2013 UCI Road World Championships, Toscana, MARA ABBOTT Italy — 13th road race Discipline: Road 2007 UCI Road World Championships, Stuttgart, Germany — 45th road race Date of birth: 11/14/1985 Height: 5’5” CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Weight: 115 lbs Two-time Giro D’Italia Internazionale Femminile Education: Whitman College winner — 2013 & 2010 Birthplace: Boulder, Colo. -

Team GB at Tokyo 2020

TOKYO 2020 OLYMPIC GAMES JULY 23 - AUGUST 08 TABLE OF Contents Team GB at Tokyo 2020 002 003 004 006 FOREWORD TEAM GB MEDIA WELCOME TO COMPETITION CONTACTS TOKYO SCHEDULE 008 010 012 TEAM GB AT HISTORICAL TEAM GB TOKYO 2020 MEDAL TALLY SPORT-BY-SPORT 3 MEDIA GUIDE FOREWORD TEAM GB MEDIA CONTACTS at an ‘away’ Games – and the media operations Director of Communications: Scott Field, Aquatics: Artistic Swimming, Marathon Judo: Katriona Bush, Katriona.Bush@ overlay in Tokyo. Please use all the links available in [email protected], & Diving Individual: David Gerty, TeamGB.com, +81 (0) 7014104115 this guide to click through to our athlete profiles or to +81 (0) 7014103668 [email protected], Modern Pentathlon: Craig Davies, follow their progress on social media +81 (0) 7014103709 Chief Press Attaché: Thomas Rowland, [email protected], +81 (0) [email protected], Athletics: Liz Birchall, 7014104053 You will find a variety of information to help you +81 (0) 7014104392 [email protected], navigate the 17 days of competition at Tokyo 2020 +81 (0) 7014104172 Rowing: Shelley Wyatt, Shelley.Wyatt@ as well as useful contacts for your time in Japan. The Deputy Chief Press Attaché and Head TeamGB.com, +81 (0) 7014104360 entire Team GB-appointed media team are here of Managing Victory: Laura Craig, Laura. Badminton: Gemma Field, [email protected], +81 (0) 7014104145 [email protected], Rugby Sevens: Charlotte Harwood, to help you, so please do be in contact during the +81 (0) 7014104053 [email protected], +81 Games if there is anything we can be of assistance Preparation Camp Media Manager: (0) 7014103957 with. -

(Professional Foreign R

ALAN JOHNSTON PETITION BBC News website users around the world have written in their thousands to demand the release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. An online petition was started on Monday, 2 April. It said: “We, the undersigned, demand the immediate release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. We ask again that everyone with influence on this situation increase their efforts, to ensure that Alan is freed quickly and unharmed.” Up to 200,000 have signed. The latest names to be added are published below. A Ashcroft Preston, England A Mitchell Linwood, Renfrewshire A Barley Nuneaton Warwickshire A Monteith Co Tyrone, N Ireland a carson glasgow, UK A MUHAMMAD MAHMUD UK A CHARNLEY ALDERSHOT, A Murphy Dubai UAE HAMPSHIRE A Opritza USA A Chevassut Oxford, UK A Sarwar London UK a clelford London UK A Simmons USA a desi london, UK A Thompson Kildare, Ireland A Devitt London, UK A Watson Angus, Scotland A Eddy Ipswich A Wilson London, UK A Fowler Dorchester, UK A, JAMA Somalia A G Deacon Peterborough, UK A. Awotwi Boston, MA A Howlett Norwich, UK A. Berry Chicago, USA A JAN Telford UK A. Bouche Washington DC A Jung Clinton, New York A. Brooks london, england A Kember London A. Burr Sandpoint, USA A M Halpern London, England A. C. Grayling London UK A. Datt Manchester, U.K. Aaron Hampton New York, USA A. Delp Greenwood, Arkansas, USA Aaron Hartz Corvallis, USA A. Fakhri a syrian kurdish in berlin/ Aaron Hedges Berlin, Germany germany Aaron Hurley Sheffield, England A. Fernandes Mumbai, India Aaron J. -

52Nd Eddie Soens Memorial Cycle Race

52nd Eddie Soens Memorial Cycle Race Photo by Larry Hickmott Saturday 2nd March 2013 Aintree Racecourse RACE MANUAL Merseyside Cycling Development Group The 52nd Eddie Soens Memorial Cycle Race 9.30am Saturday 2nd March 2013 Aintree Racecourse Club Circuit A Regional C+ handicap event for categories: Elite, 1, 2, 3, 4, Juniors & Women 30 laps of 1.64 miles/2.65 km. Total race distance: 49.2 miles/81 km Event Headquarters Kirkby Leisure Centre, Cherryfield Drive, Kirkby, Merseyside L32 8SA. Tel: 0151 443 2200 Important information for all spectators Please park as directed by race marshals. Vehicular access to the circuit is for accredited vehicles only. Spectators are only permitted in the area shown on the course plan above. All other areas, including the whole of the Golf Course are strictly out of bounds. Any violation could jeopardise our future use of the circuit. Only persons with the appropriate accreditation are permitted in the start/finish area. Your co-operation is appreciated Race Manual - Page: 2 Welcome to The Soens 2013 - the 52nd edition of Merseyside cycling’s very own ’spring classic’. This year we have again have 250 riders taking the start, proving the popularity of the race and its unique location. As well as Eddie Soens, this event also stands as a memorial to Ken Matthews, president of Kirkby Cycling Club and organiser of the race for 40 years. Whether you are riding, spectating or officiating we hope that you have a great day here at Aintree. Race Officials Organiser Carl Lawrenson Assistant Organiser Steve -

Race Manual 10–31 May 2018 Stay Ahead of the Pack

RACE MANUAL 10–31 MAY 2018 STAY AHEAD OF THE PACK Watch Tour Series on ITV4 at these times: Round One Redditch 22:45 Saturday 12 May Round Two Motherwell 17:45 Thursday 17 May Round Three Aberdeen 18:00 Monday 21 May Round Four Durham 17:15 Thursday 24 May Round Five Aberystwyth 22:00 Monday 28 May Round Six Stevenage 23:00 Wednesday 30 May Round Seven Wembley Park 23:00 Thursday 31 May Round Eight Salisbury (women’s race) 23:00 Monday 4 June #OVOTourSeries Salisbury (men’s race) 23:00 Tuesday 5 June Series Recap 10:30 Saturday 10 June www.tourseries.co.uk Please check listings and website for latest, including repeat showings 2 TOUR SERIES RACE MANUAL 2018 WWW.TOURSERIES.CO.UK FOREWORD It gives me great pleasure to welcome you all to the 10th edition of the OVO Energy Tour Series. It barely feels like 10 minutes ago that we were sitting down to discuss the creation of the Tour Series -a concept that remains unique - and then preparing for our very first event back in Milton Keynes in May 2009. Now a decade later the Series is at the very heart of the season for both our British men and women’s teams, and a key reason for the continued investment of sponsors to the domestic racing scene. We are delighted to have a fantastic new title sponsor for the Series in this of all years, and would like to welcome OVO Energy across from the Women’s Tour and Tour of Britain. -

Olympic Medalists Competing

Olympic Medalists Competing Anna Meares (AUS) Guido Fulst (GER) Gold – 2004 Women’s 500 Meter Time Trial Bronze – 2004 Men’s Points Race Bronze – 2004 Women’s Sprint Gold – 2000 Men’s Team Pursuit Natalia Tsylinskaya (BLR) Lori-Ann Muenzer (CAN) Bronze – 2004 Women’s 500 Meter Time Gold – 2004 Women’s Sprint Trial Tamilia Abassova (RUS) Sergi Escobar (ESP) Silver – 2004 Women’s Sprint Bronze – 2004 Men’s Individual Pursuit Bronze – 2004 Men’s Team Pursuit Theo Bos (NED) Silver – 2004 Men’s Sprint Joan Llaneras (ESP) Silver – 2004 Men’s Points Race Olga Slyusareva (RUS) Gold – 2000 Men’s Points Race Gold – 2004 Women’s Points Race Bronze – 2004 Women’s Road Race Jose Escuerdo (ESP) Bronze – 2000 Women’s Points Race Silver – 2004 Men’s Keirin Belem Guerrero Mendez (MEX) Chris Hoy (GBR) Silver – 2004 Women’s Points Race Gold – 2004 Men’s One Kilometer Time Trial Erin Mirabella (USA) Arnaud Tournant (FRA) Bronze – 2004 Women’s Points Race Silver – 2004 Men’s One Kilometer Time Trial Shane Kelly (AUS) Bronze – 2004 Men’s Team Sprint Bronze – 2004 Men’s Keirin Gold – 2000 Men’s Team Sprint Bronze – 2000 Men’s One Kilometer Time Trial Stefan Nimke (GER) Gold – 2004 Men’s Team Sprint Jason Queally (GBR) Bronze – 2004 Men’s One Kilometer Time Gold – 2000 Men’s One Kilometer Time Trial Trial Silver – 2000 Men’s One Kilometer Time Robert Bartko (GER) Trial Gold – 2000 Men’s Individual Pursuit Gold – 2000 Men’s Team Pursuit Rene Wolff (GER) Gold – 2004 Men’s Team Sprint Chris Newton (GBR) Bronze – 2004 Men’s Sprint Bronze – 2000 Men’s Team Pursuit Steve Cummings (GBR) Marty Nothstein (USA) Silver – 2004 Men’s Team Pursuit Gold – 2000 Men’s Sprint Silver – 1996 Men’s Sprint Rob Hayles (GBR) Silver – 2004 Men’s Team Pursuit Oxana Grishina (RUS) Bronze – 2004 Men’s Madison Silver – 2000 Women’s Sprint Paul Manning (GBR) Matthew Gilmore (BEL) Silver – 2004 Men’s Team Pursuit Bronze – 2000 Men’s Madison Bronze – 2000 Men’s Team Pursuit Karin Thurig (SUI) Mikhail Ignatiev (RUS) Bronze – 2004 Women’s Individual Time Gold – 2004 Men’s Points Race Trial . -

Sir Howard Bernstein Chief Executive

Sir Howard Bernstein Chief Executive P.O. Box 532 Town Hall Albert Square Manchester M60 2LA To: To reply please contact : Roger Fielding All Members of the City Council Tel: 0161 234 3042 Honorary Aldermen of the City of Manchester Fax : 0161 274 7017 E-mail : [email protected] 24 November 2008 Dear Councillor/Honorary Alderman, City Council Meeting - Wednesday 3 December 2008 You are summoned to attend a special meeting of the Council which will be held on Wednesday 3 rd December 2008 at 10.00 a.m. in the Council Chamber at Manchester Town Hall for the following purposes: 1. Honorary Freedom of the City of Manchester Sir Bobby Charlton CBE. Motion to be moved by the Lord Mayor and seconded by the Deputy Lord Mayor – That the Council hereby records its view that the powers entrusted to it by law of recognising distinctive and eminent service would be properly recognised by conferring the Honorary Freedom of the City of Manchester upon Sir Bobby Charlton CBE. Sir Bobby Charlton’s name is not only synonymous with football and Manchester United, but also with the highest traditions of professional sportsmanship. A long and distinguished career in club and international football justifiably earned him a worldwide reputation, but beyond his playing career he has continued to be a sterling ambassador for Manchester and for sport both at home and abroad, and a truly inspirational figure and role model for many aspiring young sportsmen and women. The Council notes that Sir Bobby was born in Ashington, County Durham in 1937. -

SCIENTISTS International Appeal to Stop 5G on Earth and in Space

International Appeal to Stop 5G on Earth and in Space SCIENTISTS ALGERIA Abraham NABET, doctorat, economics, Université Annaba, Annaba ARGENTINA Evguenia Alechine, PhD in Biochemistry and Human Genetics, Human health and sustainability, Buenos Aires María Elba Argeri, Dra. en Filosofía y Letras (Historia), History, Profesora, Dto. Política y Gestión, Facultad Ciencias Humanas, Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Tandil, Buenos Aires Pablo Bergel, Licenciado en Sociología, Praxis social y política de la crisis y transición civilizatoria, Diputado (m.c.) de la Legislatura de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, -CAPITAL FEDERAL Carolina Chioli, Biology science, University Degree, degree in Biological Sciences, specialising in Ambiental Ecology, Necochea, Buenos Aires Paula Echaniz, Biology, Psychodrama, Biologist, teacher, holistic healing, Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires Liliana Garcerant, Diagnóstico por imagen, Medicina, Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires Facundo Solanas, PhD, Political Science, Docteur en Science Politique, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3 & Doctor de la Universidad de Buenos Aires en Ciencias Sociales., Researcher and Professor, -Investigador-independiente del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) y del Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani (IIGG) de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales – UBA-Profesor Adjunto de la Facultad de Humanidades de la Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (UNMDP)., Buenos Aires ARUBA Blöff Kamu, Cancer research, Santa Cruz University,