Hume Thesis.Pdf (9.040Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornell University. Library. Administration. ~ Cornell University Library Records, [Ca.186§- 107.4 Cubic Ft

# 13\01\1082 Cornell University. Library. Administration. ~ Cornell University Library records, [ca.186§- 107.4 cubic ft. Summary: Correspondence relating to the development and administration of the library, general administrative files, administrative files of Librarians Otto Kinkeldey and Stephen McCarthy, financial records, statistical reports, and grant files. Also, records pertaining to the construction of the John M. Olin Library, including correspondence and reports of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Library Building Program; preliminary drawings; architectural drawings and blueprints; booklets, brochures, and papers relating to the dedication ceremonies; Library of Congress files, 1958-1986; ALA and ARL files, 1949-1985; Collection Development and Management Project files and user survey, 1978-1981; file relating to Cornell's decision to join RLG, 1978-1979; scrapbook of clippings of events connected with the library, 1984-1990; results of a poll of library employees, c. 1975; files of the Librarian (primarily Louis Martin and Gormly Miller) relating to departments in Olin Library including Circulation, History of Science, Icelandic, Interlibrary Loan, Manuscripts and University Archives, Maps, Microtexts, and Newspapers, the New York Historical Resources Center, and Reference, 1968-1989. Summary: Also, forty-five panels depicting the architectural evolution and design of Kroch Library; photo album of a 1990 visit by Asian dignitaries, a 1980 User Survey, a code book of detailed work done by several departments (1891•'- 1923) including special collection bookplates, and slides and audiocassettes describing the library. Restricted to ermission of office of origJ.!h_ Boxes 58-70, 73 are not restricted. Finding aids: Box lists. Finding aids: Folder lists. Includes collection #13/1/1287. -

HERE in SPIRIT Cornell Celebrates Its First-Ever ‘Virtual Reunion’

REUNION 2020 HERE IN SPIRIT Cornell celebrates its first-ever ‘virtual Reunion’ REMOTE, YET CLOSE: Student singers from the Glee Club and Chorus n June, more than 10,500 alumni from the classes of 1937 (above) join their voices on Cornelliana Night. Below: The weekend’s to 2020 participated in Reunion—a record-breaking turn events included (clockwise from top left) a book reading by Arts & out. Attendees enjoyed a Chimes concert, a tour of the Sciences Dean Ray Jayawardhana, reminiscences by well-known alumni I including Kate Snow ’91, a teach-in on racism and social justice, and a Botanic Gardens, class happy hours, and much more. tour of the Vet college. Opposite page: Scenes from the “virtual 5K.” And they did it all online. For the first time since World War II, Reunion wasn’t held far above Cayuga’s waters. Following the University’s transition to remote instruction and the postponement of Commencement due to the coronavirus pandemic, Alumni Affairs announced in late March that this year’s gathering would be virtual. “Initially there was some skepticism, particularly from those who had experienced an in-person Reunion,” notes Kate Freyer, director of Reunion and volunteer engage ment events. “It was hard to imagine those connections feeling the same way over a screen.” But by the end of the weekend, she says, the feedback was overwhelm ingly positive—and thanks to the virtual format, many alumni who wouldn’t have been able to travel to Ithaca for logistical or health reasons were able to participate. “While Cornellians certainly missed campus, I think this experience opened a lot of people’s eyes to the idea that connecting isn’t just in a place,” Freyer says. -

'54 Class Notes Names, Topics, Months, Years, Email: Ruth Whatever

Use Ctrl/F (Find) to search for '54 Class Notes names, topics, months, years, Email: Ruth whatever. Scroll up or down to May - Dec. '10 Jan. – Dec. ‘16 Carpenter Bailey: see nearby information. Click Jan. - Dec. ‘11 Jan. - Dec. ‘17 [email protected] the back arrow to return to the Jan. – Dec. ‘12 Jan. - Dec. ‘18 or Bill Waters: class site. Jan. – Dec ‘13 July - Dec. ‘19 [email protected] Jan. – Dec. ‘14 Jan. – Dec. ‘20 Jan. – Dec. ‘15 Jan. – Aug. ‘21 Class website: classof54.alumni.cornell.edu July 2021 – August 2021 Since this is the last hard copy class notes column we will write before CAM goes digital, it is only fitting that we received an e-mail from Dr Bill Webber (WCMC’60) who served as our class’s first correspondent from 1954 to 1959. Among other topics, Webb advised that he was the last survivor of the three “Bronxville Boys” who came to Cornell in 1950 from that village in Westchester County. They roomed together as freshmen, joined Delta Upsilon together and remained close friends through graduation and beyond. They even sat side by side in the 54 Cornellian’s group photo of their fraternity. Boyce Thompson, who died in 2009, worked for Pet Milk in St. Louis for a few years after graduation and later moved to Dallas where he formed and ran a successful food brokerage specializing in gourmet mixed nuts. Ever the comedian, his business phone number (after the area code) was 223-6887, which made the letters BAD-NUTS. Thankfully, his customers did not figure it out. -

Cornell Alumni Magazine

c1-c4CAMso13_c1-c1CAMMA05 8/15/13 11:02 AM Page c1 September | October 2013 $6.00 Alumni Magazine CorneOWNED AND PUBLISHED BY THE CORNELL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Overrated? Duncan Watts, PhD ’97, on why the Mona Lisa may not be all it’s cracked up to be Inside: Celebrating Reunion 2013 Dealing with deer cornellalumnimagazine.com c1-c4CAMso13_c1-c1CAMMA05 8/15/13 12:39 PM Page c2 01-01CAMso13toc_000-000CAMJF07currents 8/15/13 10:40 AM Page 1 September/October 2013 Volume 116 Number 2 In This Issue Corne Alumni Magazine 2 From David Skorton Going online 4 The Big Picture Holy cows! 6 Correspondence An activist reflects 10 Letter from Rwanda Art therapy 12 From the Hill State Street goes modern 44 16 Sports Hall of famers 20 Authors 2001: An NYC odyssey 42 Wines of the Finger Lakes Lakewood Vineyards 2012 Dry Riesling 56 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 57 Alma Matters 50 22 60 Class Notes 95 Alumni Deaths 44 It’s Complicated 96 Cornelliana War and remembrance BETH SAULNIER As the saying goes: “It’s only common sense.” But for Duncan Watts, PhD ’97, com- mon sense isn’t a dependable source of folksy wisdom—in fact, it can be reductive Currents and even dangerous. In Everything Is Obvious, Once You Know the Answer, the sociologist and network theorist explores “the wisdom and madness of crowds.” The newly minted A. D. White Professor-at-Large argues that complex problems 22 Let’s Get Together like financial crises require equally complex answers—and sophisticated analysis— More from Reunion 2013 and that the popularity of everything from the Mona Lisa to Harry Potter can essen- tially be termed a fluke. -

50Th Reunion Weekend Schedule CLASS of 1966 EVENTS • June 9-12, 2016

50th Reunion Weekend Schedule CLASS of 1966 EVENTS • June 9-12, 2016 (as of March 2016) THURSDAY, JUNE 9 CHECK-IN OPENS • 12 NOON! 3 – 3:45 PM ’66 PRIVATE CAMPUS BUS TOUR for Early Arrivals who want to remember what was where -- & why “what was there” isn’t there anymore… led by Architectural Historian (& ’66 favorite) Roberta M. Moudry ’81 4 - 5:30 PM WELCOME KICK- OFF! “CORNELL 101” VP Emerita/Student & Academic Services, Susan H. Murphy ’73 The Campus Low-Down from Cornell’s Higher-Ups: What it means to be Cornell & a Cornellian today. From Orientation to Graduation, there is no area of student life outside the classroom that did not fall under Susan’s extraordinary watch. No one knows Cornell students better. Susan will introduce us to her successor: Ryan Lombardi, new VP/Student & Campus Life Arts & Sciences Dean Gretchen Ritter ’83 will welcome The Class of 1966 as the first reunion class to visit the College’s new, glass-domed Klarman Hall Klarman attaches to the back of G.S., connecting East Avenue with a walk-through to the Arts Quad. Its stunning glass atrium sits lower than the G.S. roofline, thus maintaining the integrity of the Quad. It is the FIRST new Cornell building dedicated to the Humanities in over 100 years. Klarman’s Auditorium is the largest on the Arts Quad. 5:30 – 6:15 PM ARTS QUAD WALK to SUPPER (optional/informal) The Paths & Axes that define Cornell…and lead our feet to the Statues Make your way to dinner with an expert (& ’66 favorite), Roberta M. -

'Dqn't Stop Now,' President Rawlings Tells 1996 Graduating Class

TEACHING EXCELLENCE Three on faculty are named Stephen H. Weiss Fellows for distinguished teaching of undergraduates. ANIMAL ATTRACTION Friday's ceremonies mark the official opening of the new Veterinary Medical Center on campus. Volume 27 Number 38 June 8, 1 'DQn't stop now,' President Rawlings tells 1996 graduating class By Jacquie Powers Cornell President Hunter Rawlings, in his first commencementsinceassumingthe presi dency, urged the almost 6,000 students re ceiving degrees to enrich their lives by con tinuing the tradition and practice oflearning that they have prof ited from during their years at Cornell. "If there is one message I hope you'll take with you it is, 'Don't stop now.' You have learned a lot. You leave with a lot. But it is not enough. Keep on Rawlings learning - and your life will be rich and full," Rawlings told celebrants at the 128th Commence ment May 26. Under fair skies at Schoellkopf Field, before embarking on the heart of his com mencement message, Rawlings thanked the graduatingclass for a stringofaccomplish ments that drew rounds of applause and bursts of laughter. These included thanks for filling Lynah Rink and helping bring back Ivy titles for both the men's and women's ice hockey teams; thanks for set Frank DiM(!o'Uni~'(!rsit)'Photography ting the standard for public service; thanks Graduates enjoyed pomp, circumstance and good weather at commencement ceremonies in Schoellkopf Field. for a rainy, sane and safe Slope Day; and, to the biggest outbreak of applause, "thank not - try to rescue a stranded deer." tinued evolving to meet emerging state and and put it to good use." you for reassuring me that the Cornell tra Turning more serious, Rawlings told national needs. -

Alumni Magazine C2-C4camjf07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page C2 001-001Camjf07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1

c1-c1CAMJF07 12/22/06 1:58 PM Page c1 January/February 2007 $6.00 alumni magazine c2-c4CAMJF07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page c2 001-001CAMJF07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1 Contents JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2007 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 4 alumni magazine Features 52 2 From David Skorton Residence life 4 Correspondence Under the hood 8 From the Hill Remembering “Superman.” Plus: Peres lectures, seven figures for Lehman, a time capsule discovered, and a piece of Poe’s coffin. 12 Sports Small players, big win 16 Authors 40 Pynchon goes Against the Day 40 Going the Distance 35 Camps DAVID DUDLEY For three years, Cornell astronomers have been overseeing Spirit 38 Wines of the Finger Lakes and Opportunity,the plucky pair of Mars rovers that have far out- 2005 Atwater Estate Vineyards lived their expected lifespans.As the mission goes on (and on), Vidal Blanc Associate Professor Jim Bell has published Postcards from Mars,a striking collection of snapshots from the Red Planet. 58 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 112 46 Happy Birthday, Ezra 61 Alma Matters BETH SAULNIER As the University celebrates the 200th birthday of its founder on 64 Class Notes January 11, we ask: who was Ezra Cornell? A look at the humble Quaker farm boy who suffered countless financial reversals before 104 Alumni Deaths he made his fortune in the telegraph industry—and promptly gave it away. 112 Cornelliana What’s your Ezra I.Q.? 52 Ultra Man BRAD HERZOG ’90 18 Currents Every morning at 3:30, Mike Trevino ’95 ANATOMY OF A CAMPAIGN | Aiming for $4 billion cycles a fifty-mile loop—just for practice. -

Cornell Alumni News

CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS Vol. XIII. No. 35 Ithaca, N. V., June 7, 1911 Price 10 Cents dents of the state. Non-residents will of next week. The usual Block Week Cornelliana. pay a tuition fee of $25. The an- grinding is on in earnest. The Cornell Chapter of Phi Beta nouncement of the school may now be Kappa has elected five graduate stu- The Cornell Veterinarian is the obtained from Director Bristol of the name of a new publication which has dents to membership: George Irving Summer Session or from the College just made its appearance. The paper Dale, Ida Langdon, Bertha C. Pierce, of Agriculture. John Raymond Tuttle, and Wesley D. is to be published semi-annually by a Zinnecker; also two additional sen- With the interclass races on Beebe board composed of members of the iors: Austin P. Evans and Helen Lake Friday, the rowing season for faculty and students of the Veter- Olga Shollenberger. Sage College crews was finished. The inary College. Under a new system of military seniors won the championship, defeat- Dean H. C. Price, M. S. A., '99, and administration which will become op- ing the juniors in a preliminary race Professor W. R. Lazenby, B. Ag., '74, and the freshmen in the final. The erative on July 1, Brigadier-General of the college of agriculture of Ohio course was a quarter of a mile in Walter S. Schuyler is assigned to the State University, will be absent on length and the crews are said to have command of the brigade post at Fort leave next year, the former for Riley, Kansas. -

The Cornell Club of Hong Kong

Cornell Club of Hong Kong Big Red Bulletin + Events LAST QUARTER HIGHLIGHTS Dean Kotlikoff Reception Recap Dean Kotlikoff Reception Incoming Freshmen Class Dean Michael Kotlikoff (pictured at right) from the Veterinary School was in Hong BIG RED BULLETIN Kong to continue building relationships with Ray Kwok (Arch '01) schools in the region. The event was well- recently became father to attended by Cornell alumni, as close to 20 Mason Kwok people participated at Kee Club. Also in attendance were Mr and Mrs James Mingle - Bryant Lu's (Arch '98) Valias University Counsel and Secretary of Club House in Hong Kong Corporation as well as Alfonso Torres- recently won a Merit Award Associate Dean for Public Policy. from the Hong Kong Institute of Architects' Annual Awards Incoming Freshman Class Submit your own notes for next The results are in from the latest CAAAN issue’s Big Red Bulletin by emailing [email protected] events, including one attended by Cornell admissions officer Shawn Felton (pictured at EVENTS right) Hope to catch up at tonight Cornell University received a record high of (June 25th)'s Ivy Ball! 36,392 applications this year. 1228 students received their earlier decision acceptance last Email December while 5,306 students were offered [email protected] or regular admissions acceptance in early April check the club website to to the University’s sesquicentennial class. learn more about upcoming Students receiving offers of admission for the events. class of 2015 represent diverse backgrounds, coming from 50 states and 69 countries worldwide. In Asia, China continues to have the highest admits (102) followed by Singapore (73) and Korea (32). -

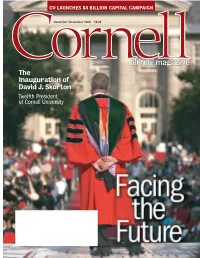

Alumni Magazine the Inauguration of David J

c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 2:22 PM Page c1 CU LAUNCHES $4 BILLION CAPITAL CAMPAIGN November/December 2006 $6.00 alumni magazine The Inauguration of David J. Skorton Twelfth President of Cornell University c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page c2 c1,c2,p1,c3,c4CAMND06 10/19/06 4:00 PM Page 1 002-003CAMND06toc 10/16/06 3:45 PM Page 2 Contents NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 2006 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 3 4 Letter From Ithaca alumni magazine French toast Features 6 Correspondence Natural selection 10 From the Hill The dawn of the campaign. Plus: Milstein Hall 3.0, meeting the Class of 2010, the ranking file, the Creeper pleads, and a new divestment movement. 16 Sports A rink renewed 18 Authors The full Marcham 35 Finger Lakes Marketplace 52 44 Wines of the Finger Lakes 46 In Our Own Words 2005 Lucas Cabernet Franc CAROL KAMMEN “Limited Reserve” To Cornell historian Carol Kammen, 62 Classifieds & Cornellians the unheard voices in the University’s in Business story belong to the students them- selves. So the senior lecturer dug into 65 Alma Matters the vaults of the Kroch Library and unearthed a trove of diaries, scrap- books, letters, and journals written by 68 Class Notes undergraduates from the founding to 109 the present.Their thoughts—now 46 assembled into a book, First-Person Alumni Deaths Cornell—reveal how the anxieties, 112 distractions, and preoccupations of students on the Hill have (and haven’t) changed since 1868.We offer some excerpts. Cornelliana Authority figures 52 Rhapsody in Red JIM ROBERTS ’71 112 The inauguration of David Skorton -

Appendix C: Artifacts and Memorials

DELTA KAPPA EPSILON FRATERNITY Delta Chi Chapter at Cornell University Office of the Alumni Historian ∆Χ of ∆ΚΕ Special Study #19: Pledge Class Research Tasks, 1987-88 Forward― The modern Delta Chi Chapter History Program began circa 1985 with a transcription of the Chapter Meeting Minutes ⎯seven bound manuscript volumes spanning the years 1870 to 1981⎯ and a survey of what was known and what was not concerning the chapter’s origins. In early 1987 the Alumni Historian (this author) devised a set of thirty-seven Research Tasks for the chapter’s pledge class to investigate. These tasks addressed aspects of the chapter’s founding, exploits of the members, and details concerning the architecture of the Cornell Deke House. Some tasks were completed successfully and some were not. This exercise was repeated in the following year with a set of twenty new tasks that were accompanied with considerable background information gleaned from the transcribed Minutes. The completion of this second campaign led to the 1988 petitions to list the lodge on the National and New York State Registers of Historic Places, and the 1993 publication of The Cornell Deke House ⎯A History of the 1893 Lodge. Later the 1994 interim report, The Deke House at Cornell: A Concise History of the Delta Chi Chapter of Delta Kappa Epsilon, 1870-1930 sprang from this work. This study is a transcription of the collected pledge program research tasks for the 1987 and 1988 campaigns. Appendix A depicts an image of 1987 Research Task #001 as an example of the manuscript forms used that year. -

President's Office and Provost's Office Files Sent to Archives July 25, 1997 (Archives Collection # 3/13/2843) Box 1 Through 22

President's Office and Provost's Office Files Sent to Archives July 25, 1997 (Archives Collection # 3/13/2843) Box 1 through 22 BOX 1 ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE STAFF 1. Vice President's Group - Misc. July 12, 1995 - Dec. 4, 1995 PRESIDENT 2. President - General May 17, 1995 - April 29, 1996 3. General Correspondence Nov. 3, 1995 - June 24, 1996 4. Genreal Correspondence June 18, 1995 - Oct. 31, 1995 a. Charles Mingo 5. condolences June 13, 1995 - June 25, 1995 6. Congratulations June 13, 1995 - June 26, 1996 7. Congratulations - Academic Promotions Oct. 16, 1995 - May 28, 1996 Assistant to Associate Professor 8. Congratulations - Academic Promotions Aug. 18, 1995 - May 28, 1996 Associate to Full Professor 9. Congratulations - New Department Chairs/ Oct. 16, 1995 - May 28, 1996 New Program Directors/New Named Professors 10. Emeritus Professors - Letters to Nov. 14, 1995 - Feb. 6, 1996 11. Invitations. - General June 25, 1995 - June 7, 1996 12. Ann Aug. 7, 1995 - April 2, 1996 a. MGL first months b. Connie 13. Affirmative Action Unit Representative Sept, 20, 1995 - NOV. 8, 1995 14. Presidential Councillors Sept. 6, 1995 - June 26, 1995 15. Presidents' Emeritus July 10, 1995 - April 15, 1996 16. Recommendations Aug. 4, 1995 - Feb. 15, 1996 17. General Contact Jan. 12, ,1995 - Feb. 19, 1996 18. Community Contact July 13, 1995 - March 15, 1996 a. Metropolitan Development Assn. 7/14/95 19. Contact - Departments June 26, 1995 - May 10, 1996 20. Contact - Non-academic Departments Aug. 7, 1995 - May 21 . 1996 a. Dianne Murphy 21. Contact - Employee June 13, 1995 - May 13. 1996 22.