TCRP Report 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nfbidlovesbiz #STOPBYSHOPBUY

NORTH FLATBUSH BID CONNECTING COMMUNITIES FOR OVER 30 YEARS Visit us at: NORTHFLATBUSHBID.NYC 282 Flatbush Avenue Brooklyn New York 11217 718-783-1685 · [email protected] Design by AGD Studio · www.agd.studio Stay connected with us: #NFBIDlovesBIZ #STOPBYSHOPBUY @NORTHFLATBUSHBK @NFBID NFBID: OUR BACKGROUND NFBID: DISTRICT MAP & BOARD MEMBERS N Take a further look: Scale of map: NFBID.COM/SHOP 1 in = 250 ft NORTH FLATBUSH BID Greetings! B45 B67 CLASS A: PROPERTY OWNERS A little over 35 years ago, a group of committed citizens joined BAM BAM ATLANTIC AVE & forces to improve the area known as North Flatbush Avenue. These 3RD AVENUE SHARP HARVEY BARCLAYS CENTER committed citizens, along with the assistance of elected officials B D N R Q WILLIAMSBURGH FULTON STREET President, Ms. Regina Cahill and city agencies, brought renewal to Flatbush Avenue beginning SAVINGS BANK with the “Triangle Parks Commission” and the North Flatbush Avenue TOWER Vice President, Mr. Michael Pintchik Betterment Committee that ultimately gave rise to the North Flatbush B37 Secretary & Treasurer, Ms. Diane Allison Business Improvement District (NFBID). This corridor along Flatbush B65 B45 ATLANTIC AVE & BARCLAYS CENTER Avenue from Atlantic Avenue towards Prospect Park connects NORTH B103 FLATBUSH 2 3 4 5 Mr. Abed Awad residential communities like Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Pacific Park BID B63 and bustling Downtown to the peaceful Prospect Park and beyond Mr. Scott Domansky 4TH AVENUE B41 with a slew of transportation links and the Avenue traveling from the B65 BARCLAYS Mr. Chris King Manhattan Bridge to the bay. B67 CENTER Mr. Matthew Pintchik Over the years, the members of the NFBID Board of Directors, BERGEN ST ATLANTIC AVENUE Mr. -

Volume 2: Main Report SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT – SESSION 2

EDINBURGH TRAM NETWORK EDINBURGH TRAM (LINE TWO) BILL Environmental Statement: Volume 2: Main Report SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT – SESSION 2 PREFACE The Edinburgh Tram Line 2 Environmental Statement is published in five volumes: • Volume 1 Non-Technical Summary • Volume 2 Environmental Statement: Main Report • Volume 3 Figures • Volume 4 Appendices to Main Report • Volume 5 Protected Species Report (Confidential) This document is Volume 2. Table of Contents VOLUME 2 ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT: MAIN REPORT ABBREVIATIONS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1-1 1.2 Tram Line 2 and the Tram Network 1-1 1.3 The Environmental Impact Assessment of Tram Line 2 1-1 1.4 The EIA Process 1-1 1.5 Relationship Between Tram Line 1 and Tram Line 2 1-2 1.6 Authors 1-2 1.7 Structure of ES 1-3 2 THE PROPOSED SCHEME 2.1 Introduction 2-1 2.2 The Need for the Scheme 2-1 2.3 Scheme Alternatives 2-2 2.4 Scheme Description 2-4 2.5 Tram Line 2 Infrastructure 2-7 2.6 The Construction Phase 2-11 2.7 Operation of Tram Line 2 2-14 3 APPROACH TO THE EIA 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Parliamentary Requirements and the EIA Regulations 3-1 3.3 The EIA Process 3-1 3.4 Approach to the Assessment of Impacts 3-2 3.5 Uncertainty, Assumptions and Limitations 3-4 3.6 Scope of the Environmental Statement and Consultation 3-6 4 POLICY CONTEXT 4.1 Introduction 4-1 4.2 Methods 4-1 4.3 National and Regional Planning Guidance 4-3 4.4 Planning Policies of The Local Authority 4-6 4.5 Summary 4-13 5 TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT 5.1 Introduction 5-1 5.2 Methods 5-1 5.3 Baseline Situation 5-4 5.4 Construction Effects -

Lease Brochure

FOR LEASE | RETAIL SPACE 1,200- 3,200 3,200 SF RetailSF Retail | Office | forOffice Lease for in Flatlands! Lease in Flatlands! 1783 Flatbush Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11210 Jacob Twena Shlomi Bagdadi 718.437.6100 718.437.6100 [email protected] [email protected] Tri State Commercial® Realty Inc | 482 Coney Island Ave | Brooklyn, NY 11218 | | tristatecr.com 1,200- 3,200 SF Retail | Office for easeL in Flatlands! 1783 Flatbush Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11210 Executive Summary OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY OVERVIEW Available SF: 1,200 - 3,200 SF 1,200- 3,200 SF Retail | Office for easeL in Flatlands! Highlights: -Logical divisions considered -Backyard Lease Rate: Upon Request -Build to Suit LOCATION OVERVIEW Located in Flatlands near the B7. B9, B41, B44, BM1, B82, and Q35 bus stops. In close proximity to the Flatbush Ave 2 and 5 train station. Nearby tenants include, Lot Size: 7,911 SF -Target -Dunkin Donuts -Chase -Duane Reade Building Size: 13,494 SF -HSBC -Starbucks -Dollar Tree -Bank of America & many more! Zoning: R5 Broker is relying on Landlord or other Landlord-supplied sources for the accuracy of said information and has no knowledge of the accuracy of it. Broker makes no representation and/or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy of such information. Jacob Twena Shlomi Bagdadi 718.437.6100 718.437.6100 [email protected] [email protected] Tri State Commercial® Realty Inc // 482 Coney Island Ave // Brooklyn, 11218 // http://tristatecr.com/ 1,200- 3,200 SF Retail | Office for easeL in Flatlands! 1783 Flatbush Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11210 Location Maps Broker is relying on Landlord or other Landlord-supplied sources for the accuracy of said information and has no knowledge of the accuracy of it. -

The Battle of Brooklyn, August 27-29, 1776 a Walking Guide to Sites and Monuments

The Battle of Brooklyn, August 27-29, 1776 A Walking Guide to Sites and Monuments Old Stone House & Washington Park 336 Third Street between Fourth and Fifth Avenues P.O. Box 150613, Brooklyn, NY 11215 718.768.3195 www.theoldstonehouse.org Using This Guide This guide is offered as a means through which visi- Transportation Resources The following sites are in geographic proximity and can be tors may experience the 1776 Battle of Brooklyn as it Walking: Due to the immense area of the battlefield and the visited together. developed in the fields, orchards, creeks, and country long distances between some of the sites, a walking tour of all sites Sites 1, 21 (The British Landing at Gravesend, Mile- lanes that later became nearly invisible in Brooklyn’s is not very practical. Nearby sites and other attractions which are stone Park, New Utrecht Liberty Pole) densely inhabited nineteenth and twentieth century within walking distance (although here, too, distances might be too Sites 11, 12 (The Red Lion Inn,* Battle Hill in urban expansion. great for some walkers) are listed for each site. Point-to-point tran- Green-Wood Cemetery) It is intended to be much more than a requiem for sit/walking directions are available from www.hopstop.com. Sites 13, 15, 25 (Flatbush Pass/Battle Pass, Mount Car: the dead and wounded of the battle. Land use evolves Curbside parking is problematic in the extreme at some Prospect, Lefferts Homestead) over time, and Brooklyn offers a prism through which locations, easier in others, and easier in general on weekends and Sites 16, 22, 24 (Litchfield Villa, Old First Re- visitors may consider nearly four centuries of the chang- holidays. -

Chapter 13: Transit and Pedestrians A. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 13: Transit and Pedestrians A. INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the transit and pedestrian travel characteristics and potential impacts associated with the proposed Atlantic Yards Arena and Redevelopment project located on an approximately 22-acre site in the Atlantic Terminal area of Brooklyn, roughly bounded by Flatbush and 4th Avenues on the west, Vanderbilt Avenue on the east, Atlantic Avenue on the north, and Dean and Pacific Streets on the south (see Figure 12-5 in Chapter 12, “Traffic and Parking”). As described in detail in earlier chapters of this environmental impact statement (EIS), in addition to an approximately 850,000 gross-square-foot (gsf) arena for use by the Nets professional basketball team and for other sporting, entertainment, and cultural events, it is anticipated that the proposed project would include residential, office, hotel, and retail uses, eight acres of publicly accessible open space, approximately 3,670 parking spaces, and an improved Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) rail yard. (As discussed in Chapter 1, the development program for the proposed project has been reduced from the program that was analyzed in the DEIS.) Also included would be internal circulation improvements at the Atlantic Avenue/Pacific Street subway station complex, and a major new on-site entrance to the complex adjacent to the arena. In addition to the arena, a total of 16 other buildings would be constructed on the eight blocks comprising the project site. These buildings are referred to as Site 5 and Buildings 1 through 15. The proposed project is expected to benefit from its location in an area with one of the densest concentrations of transit services in the City. -

124-20 B25 M&S.Qxp Layout 1

Bus Timetable Effective as of January 19, 2020 New York City Transit B25 Local Service a Between East New York and Fulton Landing If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. OMNY is the MTA’s new fare payment system. Use your contactless card or smart device to pay the fare on buses and subways. Visitomny.info for details of the rollout. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card. -

Table of Contents

Southern Brooklyn Transportation Investment Study Kings County, New York P.I.N. X804.00; D007406 Technical Memorandum #2 Existing Conditions DRAFT June 2003 Submitted to: New York Metropolitan Transportation Council Submitted by: Parsons Brinckerhoff In association with: Cambridge Systematics, Inc. SIMCO Engineering, P.C. Urbitran Associates, Inc. Zetlin Strategic Communications TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................... ES-1 A. TRANSIT SYSTEM USAGE AND OPERATION.................................................................. ES-1 B. GOODS MOVEMENT...................................................................................................... ES-2 C. SOCIOECONOMIC CONDITIONS ..................................................................................... ES-4 D. ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS .................................................................................... ES-5 E. ACCIDENTS AND SAFETY.............................................................................................. ES-5 F. PEDESTRIAN/BICYCLE TRANSPORTATION.................................................................... ES-6 CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................I-1 A. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................I-1 B. PROJECT OVERVIEW..........................................................................................................I-1 -

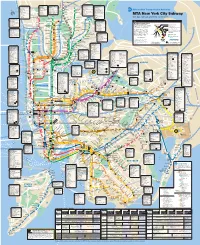

Subway Map of NY

WESTCHESTER THE BRONX PELHAM BAY R 2 k I a ORCHARD V PARK r Wakefield t E BEACH R Wakefield Wakefield–241 St m D Woodlawn A A Norwood–205 St Pelham Bay Park Van Cortlandt Pk–242 LSt 241 St Subway 2 E Subway 4 Subway A Subway D 2 6 Subway B EASTCHESTER 1 V 5 NYC Transit Bus R NYC Transit Bus P O NYC Transit Bus CITY NYC Transit Bus O NYC Transit Bus A T Eastchester Bx41-OP Webster Av/White Plains Rd R D Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av 5 Nereid Av 3 S CO T W Bx10 Riverdale 23 Bx5 Bruckner Blvd/Story Av W Bx9 Broadway/West Farms Sq A • Dyre Av A Y Bx34 Bainbridge Av 2 5 Bee-Line W254ST Bx16 E 233 St/Nereid Av Bx12 Pelham Pkwy/Bay Plaza S N 5 H Riverdale I Bee-Line Woodlawn 40 Westchester County Med Ctr N Bee-Line Bx28 E Gun Hill Rd 233 St Bx12 Orchard Beach G T 1 Yonkers/Hastings • Baychester 41 WestchesterV County Med Ctr O 4 Yonkers Bx30 Boston Rd/E Gun Hill Rd 2 5 A Bx14 Country Club–Parkchester N Av 42 New RochelleW 1C Westchester Cty Comm Coll B Bx34 Bainbridge Av 225 ST CO-OP O Bx29 Bay Plaza–City Island 20 White Plains T L R V 1T Tarrytown M T 5 CITY 225 St 222 S A D h Metro-North O MTA New York City Subway 21 White Plains B t LA MTA Bus S r 1W White Plains • D o 2 5 H CO R 1 O N QBx1 Co-op City–Flushing - 2 Yonkers 4 N L o NIA r U O t T 3 White Plains Van Cortlandt Park e 219 St BAYCHESTER Bee-Line with bus, railroad, and ferry connections S M AV 242 St VAN Woodlawn 2•5 O B THE 45 Eastchester Y Y CORTLANDT I 1 A P 4 Marble Hill–225 St N K KE AV W W CITY D RIVERDALE V PARK W R Gun Hill Rd P O Gun Hill Rd U K Williams D S E A Subway 1 A RK -

2156 Cortelyou Road, Brooklyn, Ny 11226 8,641 4 13

2156 CORTELYOU ROAD, BROOKLYN, NY 11226 13 Unit, Walk-up Building with 11 Newly Renovated Free Market Apartments | FOR SALE PROPERTY INFORMATION Block / Lot 5165 / 28 Lot Dimensions 28.65' x 100' Lot Size 2,865 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Building Dimensions 28' x 90' Stories 4 Units 13 Building Size 8,641 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Zoning R6A FAR 3.00 Buildable Area 8,595 Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Air Rights None Sq. Ft. (Approx.) Tax Class 2 Assessment (19/20) $335,149 Real Estate Taxes (19/20) $42,269 8,641 4 13 FLATBUSH Gross SF Stories Units Location PROPERTY DESCRIPTION Ariel Property Advisors is pleased to present 2156 Cortelyou Road, a 13-unit There is heavy foot traffic along the Cortelyou and Flatbush Ave intersection multifamily property located on the corner of East 22nd and Cortelyou Road in with many choices including restaurants, medical offices and stores. The area is Flatbush. well served by public transportation with the Q, 2, 5 trains and B41, B49 buses all located within walking distance to the subject property. The building stands 4 stories tall and encompasses approximately 8,641 gross square feet with 28’ of frontage and 90’ deep on a 100’ lot. Of the 13 units, 2156 Cortelyou Road presents the rare opportunity to acquire a strong cash there are eleven free-market apartments and 2 rent-stabilized apartments. The flowing, free-market property in the rapidly growing neighborhood of Flatbush. residential unit mix consists of 13 fully occupied apartments, with one (1) studio, three (3) one-bedrooms, seven (7) two-bedrooms and two (2) three-bedrooms. -

Restoring the B71 Bus

RESTORING THE B71 BUS You can get there from here! BACKGROUND Route B71 originated circa 1900 as a streetcar from the ferry at the foot of Hamilton Avenue along Union Street to Grand Army Plaza In the 1980s the B71’s western terminus was moved to Van Brunt and Union Streets and the eastern terminus to Rogers Avenue in Crown Heights Heavy traffic on Union Street east of 8th Avenue and on the Eastern Parkway side roads led to frequent delays of service The last end-to-end trips left the termini at 9:00 PM Citing declining ridership, the MTA eliminated the B71 as part of service changes in June 2010 RESTORING THE B71 Elected officials, advocacy groups, and community organizations have urged the restoration of the B71 ever since its discontinuance. The proposal before you starts from the premise that the B71’s route was so problematic, so prone to delays, as to make the route highly unreliable, deterring its use and leading to low ridership. With service ending at 9 PM, the B71 was never an option for people going to other communities for dining, entertainment, or other evening activities. SERVICE GOALS FOR A NEW B71 Frequent, reliable service Connections to many bus and subway routes Increase the number of trip generators; connections to many Schools and Houses of Worship, Parks and Cultural Institutions, and Shopping, dining, and entertainment venues PROJECT GOALS FOR A NEW B71 Eliminate causes of unreliable service on old B71 Avoid Union Street east of 7th Avenue Minimize use of Eastern Parkway Piggyback on existing bus stops as much as possible Utilize B71 bus stops that are still existing Eliminate the minimum number of parking spaces Minimize capital cost THE PROPOSAL Restore the portion of the pre-2010 B71 between Columbia Street and 7th Avenue. -

Between Ft Hamilton and Brooklyn Bridge Park

Bus Timetable Effective as of April 28, 2019 New York City Transit B63 Local Service a Between Ft Hamilton and Brooklyn Bridge Park If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

Reducing Delays on the B41 Bus

ANATOMY OF A ROUTE Reducing Delays on the B41 Bus Prepared for Transportation Alternatives NYPIRG Straphangers Campaign July 18, 2003 Schaller Consulting 94 Windsor Place, Brooklyn, NY (718) 768-3487 [email protected] www.schallerconsult.com REDUCING DELAYS ON THE B41 BUS 1 Summary The B41 Limited on Flatbush Avenue between Downtown Brooklyn and the Kings Plaza mall is one of the slowest bus routes in Brooklyn. Long travel times are produced by: • Traffic congestion around Atlantic Terminal and the Junction and within the Kings Plaza bus terminal. • Long dwell times at major transfer points, as numerous passengers board the bus. • An excessive number of closely-spaced, lightly used bus stops on Livingston Street and near Kings Plaza. The following steps address the problems on the route and would improve travel speeds and reliability of service: • Add a bus lane on Flatbush Avenue between Livingston Street and 5th Avenue, in effect inbound between 7 a.m. and noon and outbound between noon and 7 p.m. • Add a bus lane on Flatbush Avenue in the vicinity of the Junction, between Farragut Road and Avenue I, in effect throughout the day on both sides of the street. • Increase bus lane enforcement throughout the route. • Institute pre-boarding fare payment at the Atlantic Avenue and Nostrand Avenue bus stops. • Reconfigure the bus parking area at Kings Plaza to allow buses to pull in more quickly. • Replace the bus stops at Hoyt Street and Bond Street with a single intermediate stop at Elm Street. • Extend limited-stop service from Kings Highway to Kings Plaza.