Steve Redhead (Page 35) Nebula 6.2, June 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

The Indigenous Body As Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson Phd Candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada

CONTINGENT HORIZONS The York University Student Journal of Anthropology VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 (2019) OBJECTS “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest Michelle Johnson PhD candidate, Dance Studies | York University, Toronto, Canada Contingent Horizons: The York University Student Journal of Anthropology. 2019. 5(1):45–62. First published online July 12, 2019. Contingent Horizons is available online at ch.journals.yorku.ca. Contingent Horizons is an annual open-access, peer-reviewed student journal published by the department of anthropology at York University, Toronto, Canada. The journal provides a platform for graduate and undergraduate students of anthropology to publish their outstanding scholarly work in a peer-reviewed academic forum. Contingent Horizons is run by a student editorial collective and is guided by an ethos of social justice, which informs its functioning, structure, and policies. Contingent Horizons’ website provides open-access to the journal’s published articles. ISSN 2292-7514 (Print) ISSN 2292-6739 (Online) editorial collective Meredith Evans, Nadine Ryan, Isabella Chawrun, Divy Puvimanasinghe, and Katie Squires cover photo Jordan Hodgins “Not That You’re a Savage” The Indigenous Body as Animated Palimpsest MICHELLE JOHNSON PHD CANDIDATE, DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, CANADA In 1995, Disney Studios released Pocahontas, its first animated feature based on a historical figure and featuring Indigenous characters. Amongst mixed reviews, the film provoked criti- cism regarding historical inaccuracy, cultural disrespect, and the sexualization of the titular Pocahontas as a Native American woman. Over the following years the studio has released a handful of films centered around Indigenous cultures, rooted in varying degrees of reality and fantasy. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

The Modern World Through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’S a Burnt-Out Case and the Confidential Agent As Dystopian Novels

Nebula 6.2 , June 2009 The Modern World through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’s A Burnt-out Case and The Confidential Agent as Dystopian Novels. By Ayobami Kehinde What an absurd thing it was to expect happiness in a world so full of misery…. Point me out the happy man and I will point you out either egotisms, evil - or else an absolute ignorance (Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter, 1948: 117) Graham Greene was undoubtedly one of the most gifted and acclaimed novelists of the War/Post-war era in Britain. His novels reflect a constant search for new novelistic modes of expression capable of visualizing the disillusionment and malaise of the modern world. According to Waldo Clarke (1976), an enduring trait of Greene’s fiction is the willingness to look at the repulsive face of the twentieth century. Since literature mostly reflects the mood of its age and enabling contexts, Greene’s fiction dwells on the conflicts and pains of the modern world. The central burden of this discourse is to prove that Greene’s novels steadily progressed in his bold use of the convention of dystopian fiction. It has been proved elsewhere that Greene’s The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter are quintessential existential dystopian novels (See: Ayo Kehinde, 2004). However, in this present paper, an attempt is made to study more closely the dystopian features and political and ideological implications of the deployment of this convention in Greene’s The Confidential Agent and A Burnt-out Case . -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

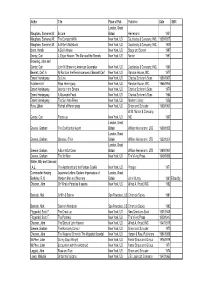

Eng Book2002

Author Title Place of Pub. Publisher Date ISBN London, Great Maugham, Somerset W. Encore Britain Heinemann 1951 Maugham, Somerset W. The Constant Wife New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1926/1927 Maugham, Somerset W. A Writer's Notebook New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1949 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House New York, US Stage and Screen 1997 Gentry, Curt J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets New York, US Norton 1991 Browning, John and Gentry, Curt John M. Browning American Gunmaker New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1964 Bennett, Cerf. A At Random the Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf New York, US Random House, INC. 1977 Ernest Hemingway By Line New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1956/1967 Hotchner A.E. Papa Hemingway New York, US Random House, INC. 1955/1966 Ernest Hemingway Islands in the Stream New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1970 Ernest Hemingway A Moveable Feast New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1964 Ernest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises New York, US Modern Library 1926 Ross, Lillian Portrait of Hemingway New York, US Simon and Schuster 1950/1961 W.W. Norton & Company, Gentry, Curt Frame-up New York, US INC 1967 London, Great Greene, Graham The Confidential Agent Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1939/1952 London, Great Greene, Graham Stamboul Train Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1932/1951 London, Great Greene, Graham A Burnt-Out Case Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1960/1961 Greene, Graham The 3rd Man New York, US The Viking Press 1949/1950 Wilder, Billy and Diamond, I.A.L. The Apartment and the Fortune Cookie New York, US Praeger 1971 Commander Hasting Japanese Letters: Eastern Impressions of London, Great Berkeley, R.N.