Indian Oculists and Quackery in Late Nineteenth Century Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Ball 2007

End of Year Issue 2007 SUMMER���������������������������������������������������� BALL 2007 ��������������� In This Issue... The Bludgeoner News ����������������������������������������������������� Tales From The Queer Side ������������������������������������������ ��������������� ����������������������������������� Sport �������������������� ����������������������������������������� From Bangor To ��������������� ������������������� Bangor The BIG Interview ������������� with the Vice ������������ Chancellor ������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������ The Great Orme ������������������������ ����������������� �������������������������������� Travel ������������������������������������������� ����������������� The Adventures of ��������������������������������������������������������� Stuart Dent Music ��������������������������������������� ����������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������� One Minute Welsh ������������������������������� � �������������������� Film ����������������������������������������� angor certainly loves its celebrities, Java Restaurant. On top of this there will be the night. Headlining this year, are the Male Voice Choir and Bangor University Adventures From especially if they have appeared in casino tables, circus entertainers and most Ordinary Boys. Trademarked by hits such as Jazz Orchestra. In the marquee, sax and Across The Pond BBig Brother. Over the past year we impressively of all, fun fair rides. -

Script Doctors and Vicious Addicts: Subcul- Tures, Drugs, and Regulation Under the ’British System’, C.1917 to C.1960

Hallam, Chris (2016) Script Doctors and Vicious Addicts: Subcul- tures, Drugs, and Regulation under the 'British System', c.1917 to c.1960. PhD thesis, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.03141178 Downloaded from: http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/3141178/ DOI: 10.17037/PUBS.03141178 Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/policies.html or alterna- tively contact [email protected]. Available under license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Script Doctors and Vicious Addicts: Subcultures, Drugs, and Regulation under the 'British System', c.1917 to c.1960 Christopher Hallam Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of London July 2016 Faculty of Public Health and Policy LONDON SCHOOL OF HYGIENE & TROPICAL MEDICINE Wellcome Trust Research Expenses Grant, no. 096640/Z/11/Z Research group affiliation: Centre for History in Public Health 1 © Christopher Hallam, 2016 2 I, Christopher Hallam, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis focuses on drug use and control in Britain, and on the previously un-researched period between the late 1920s and the early 1960s. These decades have been described by one Home Office Official as the ‘quiet times’, since it was believed that nonmedical drug use was restricted to a few hundred respectable middle class individuals. Subcultures, inhabited by those whose lives centred on drugs, were thought not to exist. -

A Comparative Critical Study of Kate Roberts and Virginia Woolf

CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PhD UNIVERSITY OF WALES, ABERYSTWYTH 2000 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. 4" Signed....... (candidate) ................................................. z3... Zz1j0 Date x1i. .......... ......................................................................... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) ......... ' .................................................... ..... 3.. MRS Date X11.. U............................................................................. ............... , STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. hL" Signed............ (candidate) .............................................. 3Ü......................................................................... Date.?. ' CULTURAL TRANSLATIONS: A COMPARATIVE CRITICAL STUDY OF KATE ROBERTS AND VIRGINIA WOOLF FRANCESCA RHYDDERCH Abstract This thesis offers a comparative critical study of Virginia Woolf and her lesser known contemporary, the Welsh author Kate Roberts. To the majority of -

Calls to Rein in Worldwide Faith, Hope and Clarity a Finger on the Media

07·04·09 Week 14 arielonline: ariel.gateway.bbc.co.uk THE BBC NEWSPAPER SO YOU THINK YOU KNOW YOUR UK – a TAKE THE NEW COJO TEST Page 8 Back TO earth: As the ◆recession bites, BBC learning’s Dig It campaign team, including Steve Goggin, pictured in White City with team members Vanessa Norris, Illy Woolfson and Ann Kelly, is encouraging a bit of self- Those salad days... sufficiency. Page 5 Calls to rein Faith, hope A finger on the in Worldwide and clarity media pulse JUST WEEKS AFTER the BBC Trust THE WITCHES were tricky but it THERE AREN’T MANY things that ◆indicated it wants a tighter focus for ◆was Voodoo sacrifice that proved too ◆stump Shepherd’s Bush GP, mother of BBC commercial activity, a DCMS select much for globe-trotting vicar Peter Owen- two, author and tv doctor Sarah Jarvis, but committee has called for Worldwide to put Jones. His spiritual odyssey for BBC Two taking her dog’s blood pressure live on air the brakes on expansion and cut out deals produced a host of insights and a handful for The One Show proved the old adage like the purchase of Lonely Planet. Page 4 of revelations. Page 10 about working with animals. Page 15 > NEED TO KNOW 2 OPINION 10 MAIL 11 JOBS 14 GREEN ROOM 16 216 News aa 00·00·08 07·04·09 NEED TO KNOW THE WEEK’S esseNTIALS NEWS BITES BotH THE BBC and ITV are backing a The Street, after writer Jimmy When is a tv licence required? McGovern suggested ITV job cuts could jeopardise the BBC One drama. -

The Bookseller 1861 a AB (16 High Street, Tunstall, Staffordshire)

The Bookseller 1861 A A.B. (16 High Street, Tunstall, Staffordshire), books wanted 150 A'Beckett, T.T., article on Punch and his progenitors 397 Abel & Sons (Northampton), books wanted 87, 384 Aberdeen, Adam, John, books wanted 384, 466 Aberdeen, Duffus, John, books wanted 151, 263, 327, 514 Aberdeen, King, G. & R., publications advertised 576 Aberdeen, Milne, A. & R., books wanted 566, 653, 936 Aberdeen, Smith, John, new and forthcoming publications 476 Aberdeen, Walker, J. (34 Upper Kirkgate Street), books wanted 567 Aberdeen, Wilson, R. & Son (Schoolhill), books wanted 467, 654 Aberdeen, Wyllie, D. & Son, books announced 163 Aberdeen, Wyllie, D. & Son, books wanted 88, 467, 515 Aberdeen, Wyllie, D. & Son, James Wyllie gives share of business to assistant 664 Abergavenny, Hancocks, George, bookseller, stationer and printer, assignment 392 Abergavenny, Hancocks, George, bookseller, stationer and printer, business sold to Mr. Meredith 472 Abergavenny, Meredith, J.S. (formerly of Burford, Oxfordshire), commences business at Abergavenny 521 Accrington, Bowker, E., bookseller, etc., business for sale advertised 864 Accrington, Maysh, Nathan, stationer, insolvency 520 Acts of Parliament, collections, William Salt seeks information on collections to help him improve list he is compiling 136 Acts of Parliament, collections, Salt asks person who bought Acts at sale to communicate with him 535 Acts of Parliament, see also Bankruptcy Act 1861 Adam, John (Aberdeen), books wanted 384, 466 Adams, Frederick, stationer, etc. (Peterborough), bankruptcy -

File Stardom in the Following Decade

Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, eccentricity and the British character actor WILSON, Chris Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus 2S>22 Sheffield S1 1WB 101 826 201 6 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, Eccentricity and the British Character Actor by Chris Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2005 I should like to dedicate this thesis to my mother who died peacefully on July 1st, 2005. She loved the work of both actors, and I like to think she would have approved. Abstract The thesis is in the form of four sections, with an introduction and conclusion. The text should be used in conjunction with the annotated filmography. The introduction includes my initial impressions of Margaret Rutherford and Alastair Sim's work, and its significance for British cinema as a whole. -

Politics and the Implementation of the New Poor Law: the Nottingham Workhouse Controversy, 1834-43

Politics and the implementation of the New Poor Law: the Nottingham Workhouse controversy, 1834-43 JOHN BECKETT University of Nottingham, UK The Nottingham workhouse case was a test of the resolve both of the Poor Law Commissioners appointed to administer the post-1834 New Poor Law, and of the strength of the Whig interest in the town’s municipal and parliamentary elections. All eyes were on the implementation of the legislation in Nottingham, partly because of the influential thinking of local administrators such as Absolem Barnett, and partly because the government needed evidence that the system of unions and workhouses set up after 1834 would actually work in industrial towns. The Nottingham case showed only too clearly that the key issue was the trade cycle, and fluctuations in the town’s hosiery and lace trades made it almost impossible to implement the terms of the legislation fully. The key battle was fought over the decision to build a new workhouse, which the Whigs favoured and the Tories resisted. KEYWORDS Nottingham, Poor Law, Barnett, poverty, workhouse, Tory, Whig, Guardians, politics, elections, less eligibility In March 1842 Absolem Barnett, clerk and relieving officer to the Nottingham Poor Law Union, moved 140 paupers from the existing St Mary's parish workhouse into a new building on Mansfield Road. In itself this was hardly an unusual act. All across the country in the wake of the 1834 legislation new workhouses were built, and inmates transferred from older buildings which were either demolished or sold. In Nottingham the move was more symbolic; it was the final action in a long and bitter struggle rooted in political conflict over the implementation of the New Poor Law. -

ALEXANDRA AFRYEA Representation: Alexandra Mclean-Williams

ALEXANDRA AFRYEA Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 31-40 Height: 5’6” Eyes: Brown Location: London FILM INFINITE – Jordan’s Mum Paramount Pictures Antoine Fuqua 6 UNdERGROUNd – Nigerian Villager Netflix/Excellent Productions Michael Bay MUM’S LIST – Macmillan Nurse Studio Soho Films Niall Johnson STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LANd Hamlet on the Rye Tracy Pellegrino -Carolyn BIG BIRdMAN – TV Announcer The Toscars Guy Ross THE MAGNIFICENT ELEVEN – Cameo Angry Badger Pictures Jonathan Wooding KHALEEJ AYLA – Women (Voice) Mo Twine S.N.U.B! – Marcia Grain Angry Badger Pictures Jonathan Glendening THE FUNNYMAN – Lisa Best Shot Films L. Nielsen THOSE WHO TRESPASS AGAINST US Gutted Film Company L. Nielsen -Pamilla Fortune MONSTERS OF THE Id – Alex Calvertfilm Laurie Calvert STOLEN CLOTHES – Grace D.O.F 4:13 Productions Christopher Cargill THE BUTTON – Mary Celtic Films Zeynep Sutherland TELEVISION EASTENdERS – Court Clerk BBC Studios Various DOCTORS – Janice Wilkinson BBC Studios Peter Fearon SILENT WITNESS– Kate Riley BBC Studios Diarmuid Goggins CARE – Senior Nurse Alice darwin LA Productions/BBC Films David Blair SILENT WITNESS – Kate Riley BBC Dairmuid Goggins CORONATION STREET – Doctor ITV Studios Duncan Foster Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, London SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY ALEXANDRA AFRYEA continued EMMERdALE – Dr Green ITV Studios Ian Bevitt CORONATION STREET – Doctor ITV Studios Ian Bevitt CELEBRITY CRIME FILES: LAdY Unsung Productions/TV One P. Franck Williams GANGSTER – Mme Stephanie St. -

Pathways from Homelessness: 2019

PATHWAYS FROM HOMELESSNESS: 2019 DELEGATE AGENDA #HomelessHealth19 Day 1: WEDNESDAY 13TH MARCH 09:00 REGISTRATION, EXHIBITION, POSTER DISPLAY AND NETWORKING Room: Sentosa 10:00 PLENARY SESSION 1: HOMELESSNESS AND MULTIPLE EXCLUSION: HOW CLOSE IS AN INTEGRATED RESPONSE? Chair’s introduction: Simon Fanshawe OBE, Partner, Diversity by Design Welcome: Alex Bax, Chief Executive, Pathway Homelessness — the national picture: Jon Sparkes, Chief Executive, Crisis Health and homelessness – the 2022 rough sleeping target Bill Thorpe, Deputy Director, Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Strategy, Homelessness Directorate, Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government Questions and discussion 11:30 REFRESHMENTS, EXHIBITION, POSTER DISPLAY AND NETWORKING Room: Sentosa 12:00 SEMINAR SEMINAR STREAM SEMINAR PATHWAY SEMINAR STREAM A1: A2: Mental Health STREAM A3: STREAM A4: STREAM A5: Housing and Primary and Research and Pathway health community care Education LIVE STREAM Podcast Podcast Filmed Filmed Room: Orchard 1 Room: Sentosa 1 Room: Sentosa 2 Room: Sentosa 3 Room: Orchard 2 Chaired by Chaired by Chaired by Chaired by Chaired by Dr Lígia Teixeira, Dr Jenny Drife, Gina Rowlands, Dr Caroline Dr Chris Sargeant, Director, Centre for Consultant Managing Director, Shulman, GP in Clinical Lead, Brighton Homelessness Psychiatrist, Lead Bevan Healthcare CIC Homeless and Inclusion Pathway Team Impact Clinician, START Team Health, King’s Health Partnership Pathway Treating patients Homeless Team & New Hospital Housing First; ending Fail to care, prepare to -

Beyond the M25: a BBC for All of the UK

Beyond the M25: A BBC for all of the UK Jana Bennett OBE Director of Vision, BBC Speech to the Royal Television Society 15 October 2008 The Commonwealth Club, London Thank you so much for coming along this evening to hear about our plans for the BBC outside of London. I am not the only American to recognise what is so precious about every part of this country. It was Bill Bryson in Notes from a Small Island who observed: ‘Can there anywhere on earth be, in such a modest span, a landscape more packed with centuries of busy, productive attainment?’ This American would like to see more attainment from every part of the UK reflected in network television production. And I am delighted to say that is exactly what the BBC is going to do. Our intention is nothing less than changing the very DNA of the BBC to bring the production of programmes closer to the audiences we serve. That means permanently increasing the production and commissioning of programmes in other parts of the country. More than ever before, it will be a BBC for all of the UK. The extensive programme that we are embarking on will boost jobs and the creative industries across the UK for both in-house and independents. There are those who doubt that moving resources on a serious scale can be achieved without jeopardising creative quality. Those that think at regional and national centres of excellence cannot possibly be sustainable. They are right to appreciate the scale of the challenge but wrong in their conclusions. -

Digital Programme

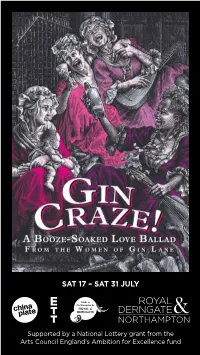

SAT 17 – SAT 31 JULY Supported by a National Lottery grant from the Arts Council England’s Ambition for Excellence fund Gin Craze! A BOOZE-SOAKED LOVE BALLAD FROM THE WOMEN OF GIN LANE BOOK AND LYRICS BY APRIL DE ANGELIS MUSIC AND LYRICS BY LUCY RIVERS A ROYAL & DERNGATE, NORTHAMPTON AND CHINA PLATE CO-PRODUCTION IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ENGLISH TOURING THEATRE Welcome to this performance of Gin Craze! It’s wonderful to have audiences back in the theatre and it’s been a joy to have a production rehearsing in the building once again, albeit under stringent Covid protocols, with the cast and core team members in a bubble for the entire rehearsal and production period. We’re very grateful to everyone who has had to put in the extra effort to make this happen. We hope you’ll agree that it’s been worth it to bring this fantastic new musical to the stage! Jo Gordon & James Dacre We would like to thank the following supporters: The Made in Northampton season is sponsored by Michael Jones Jeweller #HereForCulture Inspiring and supporting the creation of new musicals and operas With the support of Arts Council England’s Ambition for Excellence fund, Royal & Derngate has been leading a consortium including China Plate, Improbable, Mercury Musical Developments, Musical Theatre Network, Perfect Pitch and Scottish Opera, which has been working to address the barriers that prevent the creation of new, and original, musical theatre specifically developed for mid-scale regional touring. Gin Craze! has been developed as part of this three-year project which has seen Royal & Derngate and its partners support 150 artists in nurturing the creation of new musical theatre. -

Download (4MB)

‘Pursuing God’ Poetic Pilgrimage and the Welsh Christian Aesthetic A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the regulations of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature at Cardiff University, School of English, Communication and Philosophy, by Nathan Llywelyn Munday August 2018 Supervised by Professor Katie Gramich (Cardiff University) Dr Neal Alexander (Aberystwyth University) 2 CONTENTS List of Illustrations 5 List of Tables 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction - ‘Charting the Theologically-charged Space of Wales’ 9 ‘For Pilgrymes are we alle’ – The Ancient Metaphor 10 ‘Church Going’ and the ‘Unignorable Silence’ 13 The ‘Secularization Theory’ or ‘New Forms of the Sacred’? 20 The Spiritual Turn 29 Survey of the Field – Welsh Poetry and Religion 32 Wider Literary Criticism 45 Methodology 50 Chapter 1 - ‘Ann heard him speak’: Ann Griffiths (1776- 1805) and Calvinistic Mysticism 61 Calvinistic Methodism 63 Methodist Language 76 Rhyfedd | Strange / Wondrous 86 Syllu ar y Gwrthrych | To Gaze on the Object 99 Pren |The Tree 109 Fountains and Furnaces 115 Modern Responses 121 Mererid Hopwood (b. 1964) 124 Sally Roberts Jones (b.1935) 129 Rowan Williams (b.1950) 132 R. S. Thomas (1913-2000) 137 Conclusion 146 Chapter 2 - ‘Gravitating […] to this ground’ – Traversing the Nonconformist Nation[s] (c. 1800-1914) 147 3 The Hymn – an evolving form in a changing context 151 The Form 151 The Changing Context 153 The Formation of the Denominations and their effect on the hymn 159 Hymn Singing 162 The Nonconformist Nation[s] 164 ‘Beulah’