Dancing with Joy 98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Rosena Hill Jackson Resume

ROSENA M. HILL JACKSON 941-350-8566 [email protected] www.RosenaHill.com BROADWAY/New York Carousel Nettie Jack O’Brien/Justin Peck Prince of Broadway swing Harold Prince/ Susan Stroman After Midnight Rosena Warren Carlyle/Daryl Waters/Wynton Marsalis Carousel Ensemble Avery Fisher Hall/PBS “Live at Lincoln Center” Cotton Club Parade Rosena Encores City Center Lost in the Stars Mrs. Mckenzie Encores Z City Center Come Fly Away Featured Vocalist Marriott Marqui Theatre/Twyla Tharp The Tin Pan Alley Rag Monisha/Miss Lee Roundabout Theatre Co./Stafford arima,dir Oscar Hammerstein II: The Song is You Soloist Carnegie Hall/New York Pops Color Purple Church Lady Broadway Theatre Spamalot Lady of the Lake/Standby Mike Nichols dir. Imaginary Friends Mrs. Stillman & others Jack O'Brien dir. Oklahoma Ellen Trevor Nunn mus dir./Susan Stroman chor. Riverdance on Broadway Amanzi Soloist Gershwin Theater Marie Christine Ozelia Graciela Daniele dir. Ragtime Sarah’s Friend u/s Frank Galati, Graciela Daniele/Ford’s Center REGIONAL The Toymaker Sarah NYMF/Lawrence Edelson,dir The World Goes Round Woman #1 Pittsburgh Public Theater/Marcia Milgrom Dodge,dir Ragtime Sarah White Plains Performing Arts Center Man of Lamancha Aldonza White Plains Performning Arts Center Baby Pam/s Papermill Playhouse Dreamgirls Michelle North Carolina Theater Ain’t Misbehavin’ Armelia Playhouse on the Green Imaginary Friends Smart women soloist Globe Theater 1001 Nights Sophie George Street Playhouse Mandela (with Avery Brooks) Winnie Steven Fisher dir./Crossroads Brief History -

The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance

Gordon 1 Jessica Gordon 29 March 2010 Honors Thesis Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet: The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance During the mid-1860s, a ballet troupe from Paris was brought to the Academy of Music in lower Manhattan. Before the company’s first performance, however, the theatre in which they were to dance was destroyed in a fire. Nearby, producer William Wheatley was preparing to begin performances of The Black Crook, a melodrama with music by Charles M. Barras. Seeing an opportunity, Wheatley conceived the idea to combine his play and the displaced dance company, mixing drama and spectacle on one stage. On September 12, 1866, The Black Crook opened at Niblo’s Gardens and was an immediate sensation. Wheatley had unknowingly created a new American art form that would become a tradition for years to come. Since the first performance of The Black Crook, dance has played an important role in musical theatre. From the dream ballet in Oklahoma to the “Dance at the Gym” in West Side Story to modern shows such as Movin’ Out, dance has helped tell stories and engage audiences throughout musical theatre history. Dance has not always been as integrated in musicals as it tends to be today. I plan to examine the moments in history during which the role of dance on the Broadway stage changed and how those changes affected the manner in which dance is used on stage today. Additionally, I will discuss the important choreographers who have helped develop the musical theatre dance styles and traditions. As previously mentioned, theatrical dance in America began with the integration of European classical ballet and American melodrama. -

2018 Annual Dance Recital Show Order

2018 Annual Dance Recital Show Order Thursday 6:30pm Show 1. “So You Think You Can Dance Auditions”- All Company Dancers - Choreographed by: Karah DelCont, Lauren Gavin, Chelsey Geddis and Gabrielle Seabrook 2. “The Little Mermaid”- Ballet I - Choreographed by: Alexandria Sepulveda 3. “Sing”- Tap II - Choreographed by: Lauren Gavin 4. “Hold On”- Contemporary IV- Choreographed by: Lauren Gavin 5. “Ride”- Jazz III- Choreographed by: Chelsey Geddis 6. “Spoonful of Sugar”- Ballet/Tap I - Choreographed by: Michele Young 7. “Love Is A Battlefield”- Junior Company Jazz - Choreographed by: Lauren Gavin 8. “Life Is A Happy Song”- Choreographed and Performed by: Alexandria Sepulveda 9. “Halo”- Petite Company Lyrical - Choreographed by: Katharine Miller 10. “I Want You Back”- Hip Hop/Jazz - Choreographed by: Gabrielle Seabrook 11. “Better”- Tap III - Choreographed by: Lauren Gavin 12. “Drop the Game”- Acro II - Choreographed by: Daisy Pavlovics 13. “Sweet Dreams”- Jazz IV - Choreographed by: Chelsey Geddis 14. “Love on the Brain”- Choreographed and Performed by: Carly Simpson 15. “Jolly Holiday”- Father Daughter - Choreographed by: Katharine Miller 16. “Doll Shoppe”- Ballet - Choreographed by: Maura Herrera 17. “I Am”- Choreographed and Performed by: Kate Zielinski 18. “Trapped”- Senior Company Contemporary - Choreographed by: Natalie Jameson 19. “Rhythm Nation”- Jazz II - Choreographed by: Chelsey Geddis 20. “Ending”- Contemporary III - Choreographed by: Kaelynn Clark 21. “I Won’t Give Up”- Lyrical I/I.B - Choreographed by: Katharine Miller 22. “Shining”- Hip Hop IV- Choreographed by: Chelsey Geddis and Gabrielle Seabrook Intermission 23. “Riot Rhythm”- Senior Company Jazz - Choreographed by: Karah DelCont 24. “Pep Rally”- Hip Hop II - Choreographed by: Gabrielle Seabrook 25. -

The Royal Ballet Present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth Macmillan's

February 2019 The Royal Ballet present Romeo and Juliet, Kenneth MacMillan’s dramatic masterpiece at the Royal Opera House Tuesday 26 March – Tuesday 11 June 2019 | roh.org.uk | #ROHromeo Matthew Ball and Yasmine Naghdi in Romeo and Juliet. © ROH, 2015. Photographed by Alice Pennefather Revival features a host of debuts from across the Company, including Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell, Anna Rose O’Sullivan, William Bracewell, Marcelino Sambé and Reece Clarke. Principal dancer with American Ballet Theater, David Hallberg makes his debut in this production as Romeo opposite Natalia Osipova as Juliet. Production relayed live to cinemas and on Tuesday 11 June 2019. This Spring, The Royal Ballet revives Kenneth MacMillan’s 20th-century dramatic masterpiece, Romeo and Juliet. Set to Sergey Prokofiev’s seminal score, the ballet contrasts romantic pas de deux with a series For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media of vibrant ensemble scenes, set against the backdrop of 16th-century Verona as evoked by Nicholas Georgiadis’s designs. A work which has been performed by The Royal Ballet more than 400 times since it was premiered at Covent Garden in 1965, Romeo and Juliet is a classic of the 20th-century ballet repertory, and showcases the dramatic ability of the Company, as well as incorporating a plethora of MacMillan’s signature challenging choreography. During the course of this revival, Akane Takada, Beatriz Stix-Brunell and Anna Rose O’Sullivan debut as Juliet. Also performing the role during this run are Principal dancers Francesca Hayward, Sarah Lamb and Marianela Nuñez. -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 839 CS 508 906 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Crazy for You." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95] NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 902-905. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRTCE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Production Techniques; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Crazy for You; Historical Background; Musicals ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the musical play "Crazy for You," a recasting of the 1930 hit. "Girl Crazy." After a brief historical introduction to the musical play. the booklet presents biographical information on composers George and Ira Gershwin, the book writer, the director, the star choreographer, various actors in the production, the designers, and the musical director. The booklet also offers a quiz about plays. and a 7-item list of additional readings. (RS) ....... ; Reproductions supplied by EDRS ore the best that can he made from the original document, U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Ofi.co ofEaucabonni Research aria improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERIC1 Et This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization onqinallnq d 0 Minor charms have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points or view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy -1411.1tn, *.,3^ ..*. -

Young Choreographer 1920 Press Release

January 2020 The Royal Ballet announces continuation of Emerging Choreographer Programme The Royal Ballet to continue its commitment to developing choreographic talent with the recruitment of new resident Emerging Choreographer. Closing date for applications Monday 22 March 2020. The Royal Ballet is delighted to announce the continuation of its Emerging Choreographer Programme for 2020. An opportunity for emerging choreographic talent, the role is based at the Royal Opera House, and offers the successful applicant the chance to work alongside some of the world’s leading choreographers and with dancers of The Royal Ballet on developing their own choreographic projects. Inaugural Royal Ballet Emerging Choreographer Charlotte Edmonds trained at The Royal Ballet School where she was a finalist in the Ninette de Valois Junior Choreographic competition for three consecutive years. She also won the Kenneth MacMillan Senior Choreographic Competition in 2011 and 2012. During her time at The Royal Ballet, Edmonds created a number of original works including Meta, Piggy in the Middle and Sink or Swim, an innovative dance film which shines a light on the effects of depression and mental health. Edmonds has also created works for Dutch National Ballet Juniors, Norwegian National Ballet 2, Rambert School and The Grange Festival. Her most recent works include Words Fail Me, a project exploring the relationship between dance and dyslexia, and Wired to the Moon, created for Ballet Cymru. Director of The Royal Ballet, Kevin O’Hare, comments: ‘I’m thrilled to be able to open our Emerging Choreographer Programme for a second time in 2020. This is a wonderful opportunity for aspiring and emerging choreographers to hone their talent with the support For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media of the fantastic team at The Royal Ballet, as well receiving mentorship from some of the most respected and prolific choreographers working in the world today.’ Applications for the role of Royal Ballet Emerging Choreographer close on Monday 22 March 2020. -

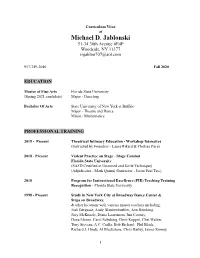

Michael Jablonski's CV

Curriculum Vitae of Michael D. Jablonski 51-34 30th Avenue #E4P Woodside, NY 11377 [email protected] 917-749-2040 Fall 2020 EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts Florida State University (Spring 2021 candidate) Major - Directing Bachelor Of Arts State University of New York at Buffalo Major - Theatre and Dance Minor - Mathematics PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 2019 - Present Theatrical Intimacy Education - Workshop Intensives (Instructed by Founders - Laura Rikard & Chelsea Pace) 2018 - Present Violent Practice on Stage - Stage Combat Florida State University (SAFD Certified in Unarmed and Knife Technique) (Adjudicator - Mark Quinn) (Instructor - Jason Paul Tate) 2018 Program for Instructional Excellence (PIE) Teaching Training Recognition - Florida State University 1998 - Present Study in New York City at Broadway Dance Center & Steps on Broadway, & other locations with various master teachers including: Josh Bergasse, Andy Blankenbuehler, Ann Reinking, Joey McKneely, Diana Laurenson, Jim Cooney, Dana Moore, Carol Schuberg, Dorit Koppel, Chet Walker, Tony Stevens, A.C. Ciulla, Bob Richard, Phil Black, Richard J. Hinds, Al Blackstone, Chris Bailey, James Kinney 1 2010 - Present One on One Studio - New York City On Camera Workshops (Selection by Audition) Instructors - Bob Krakower & Marci Phillips EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2020 - 2021 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) (Culminations - Senior Seminar Course) (Instructor - Michael D. Jablonski) 2019 - 2020 Fall & Spring Florida State University, Florida Instructor In The School of Theatre (Intro to Music Theatre Dance - New Course Developed) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. Jablonski) Graduate Teaching Assistant (Performance I - Uta Hagen Acting Class) (Instructor of Record - Chari Arespacochaga) (Performance I Lab - Uta Hagen Workshop class) (Instructor of Record - Michael D. -

At the Mission San Juan Capistrano

AT THE MISSION SAN JUAN CAPISTRANO by José Cruz González based on the comic strip “Peanuts” by Charles M. Schulz directed by Christopher Acebo book, music and lyrics by Clark Gesner additional dialogue by Michael Mayer additional music and lyrics by Andrew Lippa directed and choreographed by Kari Hayter OUTSIDE SCR 2021 • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY • 1 THE THEATRE Tony Award-winning South Coast Repertory, founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson, is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and SPRING/SUMMER 2021 SEASON Managing Director Paula Tomei. SCR is recog- nized as one of the leading professional theatres IN THIS ISSUE Get to know, or get reacquainted with, South Coast Repertory in the United States. It is committed to theatre through the stories featured in this magazine. You’ll find information about both that illuminates the compelling personal and Outside SCR productions: American Mariachi and You’re a Good Man, Charlie social issues of our time, not only on its stages but Brown, as well as the Mission San Juan Capistrano, acting classes for all ages and a through its wide array of education and engage- host of other useful information. ment programs. 6 Letter From the Artistic Director While its productions represent a balance of clas- That Essential Ingredient of the Theatre: YOU sic and modern theatre, SCR is renowned for The Lab@SCR, its extensive new-play development program, which includes one of the nation’s larg- 7 Letter From the Managing Director est commissioning programs for emerging, mid- A Heartfelt Embrace career and established writers and composers. -

Become a Season Member! Paid 17 N

PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE BECOME A SEASON MEMBER! PAID 17 N. STATE, SUITE 810 CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60602 CAROL STREAM, IL SIX SHOWS FOR AS LOW AS $120 PERMIT #1369 ORDER ONLINE OR BY PHONE! BROADWAYINCHICAGO.COM • SUBSCRIPTION 312.977.1717 CONNECT WITH US ONLINE AT GROUPS 312.977.1710 • SINGLE TICKETS 800.775.2000 BROADWAYINCHICAGO.COM/SOCIAL WORLD PREMIERE WORLD PRE-BROADWAY PRE-BROADWAY SEASON SHOW SEASON SHOW PHOTOS: MATTHEW MURPHY PHOTOS: MATTHEW MARCH 8 - 20, 2016 The quintessential backstage musical comedy classic, 42ND STREET is the song-and-dance fable of Broadway with an American Dream story and includes some of the greatest songs ever written, such as “We’re In The Money,” “Lullaby of Broadway,” “Shuffle Off To Buffalo,” “Dames,” “I Only Have Eyes For You” and of course “42nd Street.” Based on a novel by Bradford Ropes and Busby Berkeley’s 1933 movie, 42ND STREET tells the story of a starry-eyed young dancer named Peggy Sawyer who leaves her Allentown home and comes to New York to audition for the new Broadway musical Pretty Lady. When the leading lady breaks her ankle, Peggy takes over and becomes a star. With a book by Michael Stewart and Mark Bramble, music by Harry Warren and lyrics by Al Dubin, this sparkling new production will be directed by co-author Mark Bramble and choreographed by Randy Skinner, the team who Written by staged the 2001 Tony Award®-winning Best Musical Revival. WOODY ALLEN Based on the Screenplay of the Film BULLETS OVER BROADWAY by “OLD-FASHIONED, LAVISH Woody Allen and Douglas McGrath Original Direction and Choreography by SHOWMANSHIP.” —VARIETY SUSAN STROMAN APRIL 19 – MAY 1, 2016 PHOTO: CHRIS BENNION Hailed by Time Magazine as, “Musical Theatre Gold!,” BULLETS OVER BROADWAY is the hilarious musical comedy about the making of a Broadway show. -

Agnes De Mille' by Carol Easton (Little, Brown, £18.99)

Daily Telegraph July 12 1997 A choreographer with attitude Photo Karsh/Camera Press Ismene Brown wants more than just a diligent biography of a lovable monster Book Review: 'No Intermissions: the Life of Agnes de Mille' by Carol Easton (Little, Brown, £18.99) IN dance heaven, poor Agnes de Mille is resigned to being jostled by nobler colleagues. "Sprightly but peripheral" was her own assessment of her work, yet, with her 1942 ballet Rodeo and her musicals Oklahoma!, Carousel, Brigadoon and more, she invented a genre of popular stage dance that came to dominate the Western public's theatre-going for half the century. She swept away swans and fairies, and gave us new heroines: cowgirls. This was too folksy for the stern electors of modern dance or classical ballet, and yet, both then and now, debts are owed to Miss de Mille in high places. Antony Tudor, one of the great ballet innovators, was influenced by their early friendship when he made his pre-War psychological works at Ballet Rambert - works which opened the way for Kenneth MacMillan. Today Matthew Bourne's vernacular rewrites of ballet classics glance back at de Mille. But how colourless this dance generation seems in comparison. What is the equivalent nowadays of growing up in a desert called Hollywood where your Uncle Ce and his friend Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn) are rounding up extras fro the main street to put in front of their camera? Agnes's father, the playwright William, described Cecil B's first effort, 'The Squaw Man' (1914) as "the first really new form of dramatic storytelling that had been invented for some 500 years..