From Land Reform to Poo Protesting: Some Theological Reflections on the Ecological Repercussions of Economic Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics and Activism in the Water and Sanitation Wars in South Africa

Journal of Social and Political Psychology jspp.psychopen.eu | 2195-3325 Special Thematic Section on "Rethinking Health and Social Justice Activism in Changing Times" Politics and Activism in the Water and Sanitation Wars in South Africa Brendon R. Barnes* a [a] Department of Psychology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. Abstract This paper focuses on the ways in which activism is undermined in the water and sanitation wars in South Africa. The paper extends previous work that has focused on the politics of water and sanitation in South Africa and is based on an analysis of talk between activists and stakeholders in a television debate. It attempts to make two arguments. First, activists who disrupt powerful discourses of active citizenship struggle to highlight water and sanitation injustices without their actions being individualised and party politicised. Second, in an attempt to claim a space for new social movements, activists paradoxically draw on common sense accounts of race, class, geography, dignity and democracy that may limit activism. The implications for water and sanitation activism and future research are discussed. Keywords: social movements, activism, water and sanitation justice, citizenship, transitional justice Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 2018, Vol. 6(2), 543–555, doi:10.5964/jspp.v6i2.917 Received: 2018-01-18. Accepted: 2018-09-28. Published (VoR): 2018-12-21. Handling Editor: Catherine Campbell, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, United Kingdom *Corresponding author at: Department of Psychology, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 524, Auckland Park, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected] This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Read the Year-End 2014 Report Here

South African Monitor Assessing and Promoting Human Rights in South Africa Report 03 YEAR-END 2014 The ANC’s hybrid regime, civil rights and risks to business: Democratic decline and state capture in South Africa South African Monitor Assessing and Promoting Human Rights in South Africa Report 03 YEAR-END 2014 The ANC’s hybrid regime, civil rights and risks to business: Democratic decline and state capture in South Africa Report researched and compiled by Dr H. Matthee Commissioned by South African Monitor North West Free State KwaZulu-Natal Northern Cape Eastern Cape Western Cape South African Monitor aims to assess and promote human rights in general and minority rights in particular in South Africa. It provides reliable information on relevant events, analyses significant developments and signals new emerging trends. Focus areas include: Biannual reports, of which this is the third edition, portray the current state of minority and human rights in South Africa. All reports can be downloaded free of » Key dynamics of the executive; charge from the website, www.sa-monitor.com. » Democracy and the legislature; » Order, the judiciary and the rule of law; The website also provides you with an opportunity » Group relations and group rights; to subscribe to future updates, as well as download auxiliary documents and articles relevant to the above- » Freedom of expression, privacy and the media; mentioned focus areas. » Socio-economic rights and obligations; » The natural and built environment. South African Monitor www.sa-monitor.com [email protected] -

Read the Mid-Year 2015 Report Here

South African Report 04 Monitor MID-YEAR 2015 Assessing and Promoting Civil and Minority Rights in South Africa ZUMA’S HYBRID REGIME AND THE RISE OF A NEW POLITICAL ORDER: The implications for business and NGOs Report researched and compiled by Dr H. Matthee Commissioned by South African Monitor North West Free State KwaZulu-Natal Northern Cape Eastern Cape Western Cape South African Monitor aims to assess and promote civil rights in general and minority rights in particular in South Africa. It provides reliable information on relevant events, analyses significant developments and signals new emerging trends. Focus areas include: Biannual reports, of which this is the fourth edition, portray the current state of civil and minority rights in South Africa. All reports can be downloaded free of » Key dynamics of the executive; charge from the website, www.sa-monitor.com. » Democracy and the legislature; » Order, the judiciary and the rule of law; The website also provides you with an opportunity » Group relations and group rights; to subscribe to future updates, as well as download auxiliary documents and articles relevant to the above- » Freedom of expression, privacy and the media; mentioned focus areas. » Socio-economic rights and obligations; » The political risks to business. South African Monitor www.sa-monitor.com [email protected] +27-72-7284541 +31-61-7848032 SAMonitor Table of contents Table of Contents Page List of abbreviations 5 Executive summary 7 A new and symbolic political order 7 Hybrid regime 8 Part I: “Time to ditch -

Managing Disorder Jérôme Roos 31 March 2014 When an Egyptian

Managing Disorder Jérôme Roos 31 March 2014 When an Egyptian judge condemned 529 Muslim Brotherhood supporters to death this week, he underlined in one fell swoop the terrifying reality in which the world finds itself today. The revolutionary euphoria and constituent impulse that shook the global order back in 2011 have long since given way to a re-established state of control. Violent repression of protest and dissent — whether progressive or reactionary — has become the new normal. The radical emancipatory and democratic space that was briefly opened up by recent uprisings is now being slammed shut. What remains are dispersed pockets of resistance under relentless assault by the constituted power. While the mass death sentence of Islamist protesters in Egypt is an exceptionally violent and lethal instance of this process, the army’s counter-revolutionary consolidation appears to be indicative of a more generalized trend that can be felt across the globe. In Turkey, Prime Minister Erdoðan — who back in 2011 criticized Mubarak for his hard- handed repression of the popular uprising — just blocked access to Twitter and YouTube. When a 15-year-old boy, Berkin Elvan, died after spending 9 months in a coma, having been shot in the head by police while getting some bread during the Gezi protests, Erdoðan justified the killing by branding the kid a “terrorist”. In Spain, meanwhile, the right-wing government of Mariano Rajoy is reverting to old-fashioned Francoist tactics to suppress the country’s powerful anti-austerity movement. Riot police once again violently cracked down on a massive demonstration in Madrid last weekend, while authorities are eagerly drawing on the new “Citizens’ Security Law” to prosecute the arrestees, some of whom now face up to 5 years in prison. -

1 FRIDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 2020 PROCEEDINGS of the WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT the Sign † Indicates the Original Language An

1 FRIDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 2020 PROCEEDINGS OF THE WESTERN CAPE PROVINCIAL PARLIAMENT The sign † indicates the original language and [ ] directly thereafter indicates a translation. The House met at 08:00. The Deputy Speaker took the Chair and read the pra yer. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE The DEPUTY SPEAKER: You may be seated. Order! I want to take this opportunity to welcome our esteemed guests to the sitting today. Please note that for this sitting the Standing Rules of the House will apply. Further in compliance with the Powers, Privileges and Amenities of Parliament and the Provincial Legislatures Act of 2004, this entire hall, including all visitor seating areas, passages and ablution facilities will be regarded as the precincts of the Provincial Parliament. Order! Before we proceed, I would like to remind members about some of the logistical arrangements. Members, please note that by agreement with all parties there are two lecterns placed on either side of the Presiding Officer’s 2 chairs, from where the members participating in the debate will make their speeches. Members must use the lecterns on their side. Members must switch their microphones on when they are recognised by the Chair. Each member will have a separate infrared device on his or her desk, a s well as an earpiece using the channel-selection buttons. So for translation select channel 1 for Afrikaans to English translation on the right side of the unit. Select channel 2 for isiXhosa to English translation on the right side of the unit; select channel 3 for Afrikaans to isiXhosa translation on the right side of the unit; and on the right side of the unit are the channel controls and on the left are the volume controls. -

What's Left Unsaid: Rewriting and Restorying in a South African Teacher Education Classroom by Kristian D. Stewart a Dissertat

What’s Left Unsaid: Rewriting and Restorying in a South African Teacher Education Classroom by Kristian D. Stewart A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Curriculum and Practice) at the University of Michigan-Dearborn 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christopher Burke, Chair Associate Professor Stein Brunvand Professor Emerita Gloria House Professor Joe Lunn South African Site Supervisor: Associate Professor Eunice Ivala, Cape Peninsula University of Technology © Kristian D. Stewart 2016 i Dedication “We are one, but we’re not the same. We have to carry each other” “One” by U2. “i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)” E.E. Cummings. I dedicate this work to the 2014 DST facilitators’ cohort. Many thanks are due to these phenomenal students who allowed me to enter their classroom-and their lives-as I completed this study. Without their kindness, knowledge, and just overall unselfish willingness to help, I would have never gained the insight required to write this dissertation. Graeme, in particular, not only got me hooked on rugby, but he assisted me in this endeavor from the very first moment I stepped on campus through the duration of this project. I cannot stress how grateful I am for the working relationship--and now friendship after the fact--that Graeme and I have established. This sentiment of friendship and gratitude also extends to Mia and Tayla and Pieter and Luniko, to Andre, Sisipha, and Felix. You are all such amazing human beings, such incredible teachers, and my life is definitely better because I now share it with all of you. -

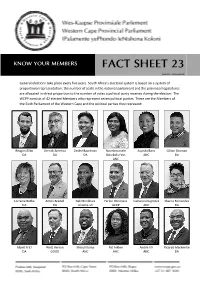

Fact Sheet 23

KNOW YOUR MEMBERS FACT SHEET 23 REVISION 1, 20 March 2020 General elections take place every five years. South Africa’s electoral system is based on a system of proportional representation: the number of seats in the national parliament and the provincial legislatures are allocated in direct proportion to the number of votes a political party receives during the election. The WCPP consists of 42 elected Members who represent seven political parties. These are the Members of the Sixth Parliament of the Western Cape and the political parties they represent: Reagan Allen Derrick America Deidré Baartman Ntombezanele Ayanda Bans Gillion Bosman DA DA DA Bakubaku-Vos ANC DA ANC Lorraine Botha Anton Bredell Galil Brinkhuis Ferlon Christians Cameron Dugmore Sharna Fernandez DA DA Al Jama-ah ACDP ANC DA Albert Fritz Brett Herron Mesuli Kama Pat Lekker Andile Lili Ricardo Mackenzie DA GOOD ANC ANC ANC DA Bonginkosi Madikizela Nosipho Makamba-Botya Anroux Marais Peter Marais Pat Marran Matlhodi Maseko DA EFF DA FFP ANC DA David Maynier French Mbombo Ivan Meyer Daylin Mitchell Masizole Mnqasela Lulama Mvimbi DA DA DA DA DA ANC Ntomi Nkondlo Wendy Philander Khalid Sayed Beverley Schäfer Debbie Schäfer Tertuis Simmers ANC DA ANC DA DA DA Danville Smith Andricus vd Westhuizen Mireille Wenger Alan Winde Rachel Windvogel Melikhaya Xego ANC DA DA DA ANC EFF Democratic Alliance (24 seats) African National Congress (12 seats) Economic Freedom Fighters (2 seats) Tel 021 481 4300 Cell 078 087 8800 Cell 078 174 3900 GOOD (1 seat) African Christian Democratic Party (1 seat) Freedom Front Plus (1 seat) Al Jama-ah (1 seat) Tel 021 518 0890 Cell 078 340 4574 Tel 021 487 1811 Tel 021 487 1832 . -

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014

ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA 2014 ELECTION UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA October 2014 Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa PO Box 740 Auckland park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 011 381 6000 Fax: +27 011 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 978-1-920446-45-1 © EISA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of EISA. First published 2014 EISA acknowledges the contributions made by the EISA staff, the regional researchers who provided invaluable material used to compile the Updates, the South African newspapers and the Update readers for their support and interest. Printing: Corpnet, Johannesburg CONTENTS PREFACE 7 ____________________________________________________________________ ELECTIONS IN 2014 – A BAROMETER OF SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICS AND 9 SOCIETY? Professor Dirk Kotze ____________________________________________________________________ 1. PROCESSES ISSUE 19 Ebrahim Fakir and Waseem Holland LEGAL FRAMEWORK 19 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN ELECTORAL LAW 21 ELECTION TIMETABLE 24 ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 25 NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS OF ELECTORAL AUTHORITY 26 ELECTORAL SYSTEM 27 VOTING PROCESS 28 WORKINGS OF ELECTORAL SYSTEM 29 COUNTING PROCESS 30 2014 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS – VOTER REGISTRATION 32 STATISTICS AND PARTY REGISTRATION ____________________________________________________________________ 2. SA ELECTIONS 2014: CONTINUITY, CONTESTATION OR CHANGE? 37 THE PATH OF THE PAST: SOUTH AFRICAN DEMOCRACY TWENTY YEARS ON 37 Professor Steven Friedman KWAZULU-NATAL 44 NORTH WEST 48 LIMPOPO 55 FREE STATE 59 WESTERN CAPE 64 MPUMALANGA 74 GAUTENG 77 ____________________________________________________________________ 3 3. -

Assessing Stakeholder Perceptions in Participatory Infrastructure Upgrades – a Case Study of Project Silvertown in Cape Town

Assessing Stakeholder Perceptions in Participatory Infrastructure Upgrades – a Case Study of Project Silvertown in Cape Town By: Shamiso Kumbirai Dissertation presented for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Civil Engineering Department of Civil Engineering: Faculty of the Built Environment University of Cape Town University of Cape Town Supervisor: Co-Supervisor: Nicky Wolmarans Prof. Ulrike Rivett The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to following people for their assistance with this dissertation: • My wonderful supervisor and co-supervisor Nicky Wolmarans and Ulrike Rivett. My postgraduate journey was considerably easier thanks to your guidance and patience during this process. • The iCOMMS research team. Being a part of a research unit has been so beneficial in the development of my research, and has also allowed me the opportunity to expand my learning and foster new friendships with researchers involved in work of a similar nature. • Finally, I would like to thank my family for their encouragement and understanding throughout this process. i Plagiarism declaration I, SHAMISO KUMBIRAI, know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all the work in the document, save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. This thesis/dissertation has been submitted to the Turnitin module and I confirm that my supervisor has seen my report and any concerns revealed by such have been resolved with my supervisor. -

Rethinking Health and Social Justice Activism in Changing Times"

Journal of Social and Political Psychology jspp.psychopen.eu | 2195-3325 Special Thematic Section on "Rethinking Health and Social Justice Activism in Changing Times" Activism in Changing Times: Reinvigorating Community Psychology – Introduction to the Special Thematic Section Flora Cornish* a, Catherine Campbell b, Cristián Montenegro c [a] Department of Methodology, London School of Economics & Political Science, London, United Kingdom. [b] Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics & Political Science, London, United Kingdom. [c] Millennium Institute for Research on Depression and Personality, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, Santiago, Chile. Abstract The field of community psychology has for decades concerned itself with the theory and practice of bottom-up emancipatory efforts to tackle health inequalities and other social injustices, often assuming a consensus around values of equality, tolerance and human rights. However, recent global socio-political shifts, particularly the individualisation of neoliberalism and the rise of intolerant, exclusionary politics, have shaken those assumptions, creating what many perceive to be exceptionally hostile conditions for emancipatory activism. This special thematic section brings together a diverse series of articles which address how health and social justice activists are responding to contemporary conditions, in the interest of re-invigorating community psychology’s contribution to emancipatory efforts. The current article introduces our collective conceptualisation of these ‘changing times’, the challenges they pose, and four openings offered by the collection of articles. Firstly, against the backdrop of neoliberal hegemony, these articles argue for a return to community psychology’s core principle of relationality. Secondly, articles identify novel sources of disruptive community agency, in the resistant identities of nonconformist groups, and new, technologically-mediated communicative relations. -

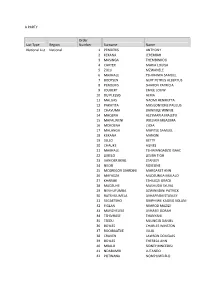

A PARTY List Type Region Order Number Surname Name National List National 1 PENDERIS ANTHONY 2 KEKANA JEREMIAH 3 MASINGA THEMBIN

A PARTY Order List Type Region Number Surname Name National List National 1 PENDERIS ANTHONY 2 KEKANA JEREMIAH 3 MASINGA THEMBINKOSI 4 CARTER MARIA LOUISA 5 ZULU MZWANELE 6 MAKHALE TSHIFHIWA SAMUEL 7 BOOYSEN GERT PETRUS ALBERTUS 8 PENDERIS SHARON PATRICIA 9 JOUBERT EMILE LOUW 10 DU PLESSIS ALMA 11 MALGAS NAOMI HENRIETTA 12 PAKATITA MASILONYONE PAULUS 13 CHAVUMA BAWINILE WINNIE 14 MAQENA ALEYMARIA MALEFU 15 MAPALWENI WILLIAM MBAZIMA 16 MOKOENA LYDIA 17 MHLANGA MAPITLE SAMUEL 18 KEKANA MANONI 19 SELLO BETTY 20 CHAUKE AGNES 21 MAKHALE TSHIMANGADZO ISAAC 22 LEBELO LESIBA TIGH 23 VAN DER BERG STANLEY 24 NKOSI ROSELINE 25 MCGREGOR GIARDINI MARGARET ANN 26 MAFADZA MUDZUNGA MULALO 27 KHARIBE TSHILIDZI GRACE 28 MADZUHE MASHUDU SYLVIA 29 NEVHUFUMBA AZWINNDINI PATRICK 30 RATSHILUMELA AVHAPFANI STANLEY 31 SEGAETSHO SIMPHIWE KAGISO XOLANI 32 FIGLAN NIMROD MAZIZI 33 MUNZHELELE AVHASEI DORAH 34 TSHIVHASE THANYANI 35 TSEDU MLUNGISI DANIEL 36 BOYLES CHARLES WINSTON 37 ROOIBAATJIE JULIA 38 CRAVEN LAWSON DOUGLAS 39 BOYLES THERESA ANN 40 MBALO SIDNEY MNCEDISI 41 NDABAMBI LUTANDO 42 POTWANA NOMPUMELELO Order List Type Region Number Surname Name 43 MASITHI MAKHADO 44 MADZUHE GLORY MUTUVHIWA 45 MUKWEVHO MUOFHE JEANETH 46 NEMARANZHE AZWIHANGWISI MARCIA 47 MATHOHO MAANDA MICHAEL 48 MAKHWATHANI AZWIHANGWISI PORTIA 49 MKHONTO CLIFFORD ADVICE 50 MAKHWATHANI NTHAMBELENI MAVIS 51 RANDIMA BETTY 52 GOGORO RUDZANI 53 MUKWEVHO LIVHUWANI JEREMIAH 54 APPOLLIS DAVID 55 DITLHAKE DUMEKUBE DANIEL 56 MAHOMED SHAHEED 57 ISMAIL‐MUKADDAM IMRAAHN 58 MULEKA MXOLISI EDWARD 59 SEKETE -

2013 State of the Province Address by Premier Helen Zille 22 February 2013 the Honourable Speaker Honourable Members of the Prov

2013 State of the Province Address by Premier Helen Zille 22 February 2013 The Honourable Speaker Honourable members of the Provincial Cabinet The Honourable Mayor of Cape town The Honourable leader of the Opposition Members of the Diplomatic Corps Honourableleaders of political parties Honourablemembers of the Provincial Legislature Director General of the Western Cape Heads of Provincial Departments Leaders of Local government Religious leaders Community leaders Colleagues and friends and Most important: all citizens of the Western Cape Welcome to everyone here today. Namkelekile nonke apha namhlanje. ‘n Hartlike warm welkom aan almal hier vandag. Speaker, Thank you for this opportunity to report back on the progress we are making towards our goal of ensuring that every citizen in this province has real opportunities to use their freedom to live a life they value. Many challenges remain, but as long as we progress every day, as far and as fast as possible, we will achieve our objectives. I would like to welcome two special guests to the House today - Dr Cleve Robertson, Director of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and Mr Phumzile Papu, the Provincial Ambulance Chief who manage 1,522 emergency medical staff across the province. Today we pay tribute to every member of the EMS team. Every day you save people’s lives by freeing them from the mangled wrecks of motor vehicles, or lifting them off one of our mountains, or simply getting them to a hospital in time. This year, the extraordinary skills of our divers, Mr Fabian Higgins and Mr Elvin Stoffels, saved the lives of people trapped in freezing water underneath the overturned Miroshga.