A STUDY on HEALTH VULNERABILITIES of URBAN MIGRANTS in the GREATER NAIROBI International Organization for Migration (IOM)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya a Case Study Analysis of Kibera

Urban and Regional Planning Review Vol. 4, 2017 | 21 Slum toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya A case study analysis of Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru Melissa Wangui WANJIRU*, Kosuke MATSUBARA** Abstract Urban informality is a reality in cities of the Global South, including Sub-Saharan Africa, which has over half the urban population living in informal settlements (slums). Taking the case of three informal settlements in Nairobi (Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru) this study aimed to show how names play an important role as urban landscape symbols. The study analyses names of sub-settlements (villages) within the slums, their meanings and the socio-political processes behind them based on critical toponymic analysis. Data was collected from archival sources, focus group discussion and interviews, newspaper articles and online geographical sources. A qualitative analysis was applied on the village names and the results presented through tabulations, excerpts and maps. Categorisation of village names was done based on the themes derived from the data. The results revealed that village names represent the issues that slum residents go through including: social injustices of evictions and demolitions, poverty, poor environmental conditions, ethnic groupings among others. Each of the three cases investigated revealed a unique toponymic theme. Kibera’s names reflected a resilient Nubian heritage as well as a diverse ethnic composition. Mathare settlements reflected political struggles with a dominance of political pioneers in the village toponymy. Mukuru on the other hand, being the newest settlement, reflected a more global toponymy-with five large villages in the settlement having foreign names. Ultimately, the study revealed that ethnic heritage and politics, socio-economic inequalities and land injustices as well as globalization are the main factors that influence the toponymy of slums in Nairobi. -

Slum Profiles | Pumwani Division EASTLEIGH NORTH

110 | Slum Profiles | Pumwani Division EASTLEIGH NORTH BAHATI EASTLEIGH SOUTH PUMWANI KAMUKUNJI Nairobi Inventory | 111 The last eviction threat was by Chief Githinji in 1990 but thereafter the residents petitioned the Nairobi City Council and got allotment let- ters for plots of 25 by 60 sq. feet each. However, the allocation process left out some residents who have resorted to designated social spaces, paths and the riparian reserves. The settlement occupies 30 acres of govern- ment land registered as Plot No. LR 16667 and extends into the riparian reserve of Nairobi Riv- er. The population is estimated at about 6000. There are 702 households with an average occu- pancy of 8 persons per household, with children making 75% of the population. There are a total of 702 residential structures, with about 3600 rooms measuring 10 square feet in size and mostly constructed using iron sheets. A few mud and stone structures are coming up, especially after the City Council subdivided the land and issued allotment let- ter to the residents. 112 | Slum Profiles | Pumwani Division Rental rates range from Kshs. 500 to 1200 per room depending on the construction materials used. • There are only two piped water points in the • Residents rely on Bahati, Jericho and Jeru- settlement owned by the Nairobi Water Com- salem Health Centres for outpatient services pany, and the residents are in negotiation with and private clinics for emergency medical con- the company on terms of supply and manage- cerns. Common ailments include malaria, ty- ment. phoid, TB, HIV/AIDS and related opportunistic infections. • The settlement has one latrine built with the assistance from the Undugu Society. -

County Integrated Development Plan (Cidp) 2018-2022

COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN (CIDP) 2018-2022 WORKING DRAFT NOVEMBER, 2017 Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page ii COUNTY VISION AND MISSION VISION “The city of choice to Invest, Work and live in” MISSION To provide affordable, accessible and sustainable quality service, enhancing community participation and creating a secure climate for political, social and economic development through the commitment of a motivated and dedicated team. Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iii Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iv FOREWORD Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page v Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page vi TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTY VISION AND MISSION ............................................................................................. iii FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ......................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF PLATES ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .................................................................................... xiv GLOSSARY OF COMMONLY USED TERMS ..................................................................... -

Exploring the Spatial Distribution of PLWA in Nairobi City

Exploring the Spatial Distribution of PLWA in Nairobi City Moses Murimi NGIGI ナイロビにおける PLWA の空間的分布 ギギ、モセス・ムリミ Abstract 発展途上国においては,都市の急激な成長によりインフラ整備や人口増加率,貧困層の分布, 環境の悪化など,様々な社会的格差が発生しており,HIV/AIDS の流行が空間的に極めて不均 一となることが懸念されている.本研究は,エイズと共存する人々(PLWA)に対する調査により, ナイロビにおけるエイズの流行の空間的な特性を示すものである.PLWA の分布とナイロビ住民 の人口密度や社会・経済的属性との関係を,GIS を用いて分析した.その結果,ナイロビの複雑 な都市構造が明示された.また,人口密度の高い地域では,PLWA が多くなる傾向にあることが 明らかとなった.ただし,GIS を援用した分析だけではエイズの空間的分布の特性とナイロビ住民 の社会・経済的属性との関係を明確にできず,さらなる調査方法の検討が必要である. Keywords: HIV/AIDS (エイズ), PLWA (HIV/AIDS 感染者), spatial distribution characteristics (空間的分布の特性), Nairobi city (ナイロビ) 1. Introduction whose objective was to identify the spatial characteristic of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the city of Nairobi. Using Emphasis on regional and national differentials in the visualization strength of geographic information prevalence of HIV often conceals substantial systems (GIS), the residential distribution pattern of the within-country variation in the burden of the AIDS PLWA is analysed against the density and epidemic (Zulu, E.M et al. 2004). Surveillance data socio-economic profile of the city’s population. from variety of sources has shown that urban areas have higher HIV prevalence rates than rural areas. HIV sentinel surveillance in Kenya has also shown the prevalence to be higher in the urban areas as compared to the rural (see Figure 1). In 2004, HIV surveillance results for Nairobi city, also an administrative province, were second after Nyanza, among the eight administrative provinces of Kenya. It was also estimated that about 40% of the urban adult population infected with HIV/AIDS in Kenya resided in Nairobi. Nairobi, similar in characteristic to other African cities; high population growth rate, high unemployment levels, urban poverty, high population densities, and heterogeneous population from different cultural backgrounds present a scenario where the HIV/AIDS pandemic can vary in many ways. -

Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs EVIDENCE REPORT No 130 IDSAddressing and Mitigating Violence Tangled Ties: Al-Shabaab and Political Volatility in Kenya Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 The IDS programme on Strengthening Evidence-based Policy works across seven key themes. Each theme works with partner institutions to co-construct policy-relevant knowledge and engage in policy-influencing processes. This material has been developed under the Addressing and Mitigating Violence theme. The material has been funded by UK aid from the UK Government, however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies. AG Level 2 Output ID: 74 TANGLED TIES: AL-SHABAAB AND POLITICAL VOLATILITY IN KENYA Jeremy Lind, Patrick Mutahi and Marjoke Oosterom April 2015 This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are clearly credited. First published by the Institute of Development Studies in April 2015 © Institute of Development Studies 2015 IDS is a charitable company limited by guarantee and registered in England (No. 877338). Contents Abbreviations 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive summary 4 1 Introduction 6 2 Seeing like a state: review of Kenya’s relations with Somalia and its Somali population 8 2.1 The North Eastern Province 8 2.2 Eastleigh 10 2.3 -

Chapter 5: Nairobi and Its Environment

145 “Cities can achieve more sustainable land use if municipalities combine urban planning and development with environmental management” -Ann Tibaijuki Executive Director UN-HABITAT Director General UNON 2007 (Tibaijuki 2007) Chapter 5: Nairobi and its Environment airobi’s name comes from the Maasai phrase “enkare nairobi” which means “a place of cool waters”. It originated as the headquarters of the Kenya Uganda Railway, established when the Nrailhead reached Nairobi in June 1899. The city grew into British East Africa’s commercial and business hub and by 1907 became the capital of Kenya (Mitullah 2003, Rakodi 1997). Nairobi, A Burgeoning City Nairobi occupies an area of about 700 km2 at the south-eastern end of Kenya’s agricultural heartland. At 1 600 to 1 850 m above sea level, it enjoys tolerable temperatures year round (CBS 2001, Mitullah 2003). The western part of the city is the highest, with a rugged topography, while the eastern side is lower and generally fl at. The Nairobi, Ngong, and Mathare rivers traverse numerous neighbourhoods and the indigenous Karura forest still spreads over parts of northern Nairobi. The Ngong hills are close by in the west, Mount Kenya rises further away in the north, and Mount Kilimanjaro emerges from the plains in Tanzania to the south-east. Minor earthquakes and tremors occasionally shake the city since Nairobi sits next to the Rift Valley, which is still being created as tectonic plates move apart. ¯ ,JBNCV 5IJLB /BJSPCJ3JWFS .BUIBSF3JWFS /BJSPCJ3JWFS /BJSPCJ /HPOH3JWFS .PUPJOF3JWFS %BN /BJSPCJ%JTUSJDUT /BJSPCJ8FTU Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ/BUJPOBM /BJSPCJ/PSUI 1BSL Conference Centre /BJSPCJ&BTU The Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ%JWJTJPOT Conference Centre, located in the ,BTBSBOJ 1VNXBOJ ,BKJBEP .BDIBLPT &NCBLBTJ .BLBEBSB heart of Nairobi's Central Business 8FTUMBOET %BHPSFUUJ 0510 District, has a 33-story tower and KNBS 2008 $FOUSBM/BJSPCJ ,JCFSB Kilometres a large amphitheater built in the Figure 1: Nairobi’s three districts and eight divisions shape of a traditional African hut. -

TERRORISM THREAT in the COUNTRY A) Security Survey

TERRORISM THREAT IN THE COUNTRY a) Security Survey In 2011, the threat of terrorism in the country rose up drastically largely from the threat we recorded and the attacks we began experiencing. Consequently, the service initiated a security survey on key installations and shopping malls. The objective was to assess their vulnerability to terrorist attacks and make recommendations on areas to improve on. The survey was conducted and the report submitted to the Police, Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Tourism. Relevant institutions and malls were also handed over the report. Subsequent security surveys have continued to be conducted. As with regard to the Westgate Mall which was also surveyed, the following observations and recommendations were made as per the attached matrix. Situation Report for 21.09.12 - Serial No.184/2012 Two suspected Al Shabaab terrorists of Somali origin entered South Sudan through Djibouti, Eritrea and Sudan and are suspected to be currently in Uganda waiting to cross into Kenya through either Busia or Malaba border points. They are being assisted by Teskalem Teklemaryan, an Eritrean Engineer with residences in Uganda and South Sudan. The duo have purchased 1 GPMG; 4 hand grenades; 1 bullet belt; 5 AK 47 Assault Rifles; unknown number of bullet proof jackets from Joseph Lomoro, an SPLA Officer, and some maps of Nairobi city, indicating that their destination is Nairobi. Maalim Khalid, aka Maalim Kenya, a Kenyan explosives and martial arts expert, has been identified as the architect of current terrorist attacks in the country. He is associated with attacks at Machakos Country Bus, Assanands House in Nairobi and Bellavista Club in Mombasa. -

Thrombosis in Africa: Past, Present and Future

THROMBOSIS IN AFRICA: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE ThrombosisThrombosis in Africa:Africa: Past,Past, PresentPresent andand Future FebruaryFuture 28th - March 1st, 2018 Four Points Sheraton Hotel, Hurlingham,February 28th Nairobi - March - 1st,Kenya 2018 Four Points Sheraton Hotel, Hurlingham, Nairobi - Kenya PROGRAMME 1 THROMBOSIS IN AFRICA: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE Day One: Wednesday, February 28, 2018 TIME EVENT 8:45 AM Registration 9:00 AM THEME OF SESSION: STATUS OF THROMBOSIS IN AFRICA Dr M. D. Maina - Chair of session What is the most reasonable approach to diagnose and treat bleeding disorders in country/region and beyond? What are the next steps to improve management? Prof Malkit Riyat - Kenya The presentation will give regional experiences, perspectives and how to move forward 9:25AM Overview of The New Anticoagulants Dr Anne Mwirigi - Kenya 9:50AM Thrombosis Prophylaxis in country/region Dr Harun Otieno - Kenya The presentation will give the country/regional perspective in prophylaxis and treatment of thrombosis, including developments in developing national guidelines 10:15 AM QUESTIONS FOR SESSION SPEAKERS 10:40 AM REFRESHMENTS 11:10 AM THEME OF SESSION THROMBOTIC DISORDERS Dr Anne Mwirigi - Chair of session 11:35 AM Diagnosis of Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism in Country/region Current State Dr Anders Barasa - Kenya Thrombosis in Sickle Cell Disorder Dr. Elizabeth Kagotho - Kenya Participants will be presented with local country specific aspects in diagnosis and presentation of Thromboses and pulmonary embolism in country The presentation will focus on emerging paradigm shift relating procoagulant factors such as RBC TF decryption, PS expression, endothelial vWF release and microparticles in aetiology of thrombosis associated with Sickle cell crisis. -

Failure to Deliver

in Kenyan Health Facilities Failure to Deliver Human Rights Violations of Women’s Failure to Deliver Violations of Women’s Human Rights in Kenyan Health Facilities © 2007 Center for Reproductive Rights and ISBN: 1-890671-35-5 Federation of Women Lawyers–Kenya 978-1-890671-35-5 Printed in the United States Center for Reproductive Rights 120 Wall Street, 14th Floor Any part of this report may be copied, translated, or New York, NY 10005 adapted with permission from the authors, provided United States that the parts copied are distributed free or at cost Tel +1 917 637 3600 (not for profit) and the Center for Reproductive Fax +1 917 637 3666 Rights and the Federation of Women Lawyers–Kenya [email protected] are acknowledged as the authors. Any commercial www.reproductiverights.org reproduction requires prior written permission from the Center for Reproductive Rights or the Federation of Federation of Women Lawyers—Kenya (FIDA) Women Lawyers–Kenya. The Center for Reproductive Amboseli Road off Gitanga Road Rights and the Federation of Women Lawyers–Kenya PO Box 46324-00100 would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials Nairobi, Kenya in which information from this report is used. Tel 254 (020) 3870444 Fax 254 (020) 3876372 [email protected] Cover photo: © Stock Connection RM, 2007 www.fidakenya.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ..................................................................................... 7 -

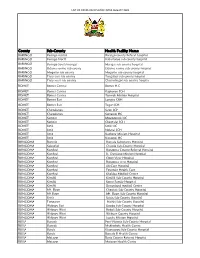

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Settlements in Transformation: Impacts of the Emerging Housing Typologies

SETTLEMENTS IN TRANSFORMATION: Impacts of the emerging housing typologies on slums in Nairobi, a case of Mukuru Kwa Njenga settlement JAMES WANYOIKE WANJIKU M.A. (Planning), UoN. B63/60576/2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the award of the Degree of Master in Urban and Regional Planning, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Nairobi UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING October, 2014 i | P a g e Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been presented for award of a degree in any other university. James Wanyoike Wanjiku ……………………………………………………. …………………….. ……………………… Name of student Date Signature This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors Professor R.A. Obudho ……………………………………………………. …………………….. ……………………… Supervisor Date Signature Professor P.N. Ngau ……………………………………………………. …………………….. ……………………… Supervisor Date Signature ii | P a g e ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, my greatest gratitude goes to the Centre for Urban Research and Innovations (CURI) whose financial support made my studies successful. The Centre gave me more than just financial support; I got a chance to enhance my skills in the field I love – technology application in planning and research. I also appreciate the community guides (who are residents of Mukuru kwa Njenga), and especially the Wapewape village chairman Mr. Kimondo for introducing me to the community. Even much greater appreciation goes to the residents of Mukuru kwa Njenga for giving me their time and participating in the research. Much gratefulness foes to Patrick (a savings group mobiliser) working at Akiba Mashinani Trust. He provided m e w i t h field assistance all through the study. -

Farming in the City of Nairobi

African Studies Centre Leiden The Netherlands FARMING IN THE CITY OF NAIROBI Dick Foeken and Alice Mboganie Mwangi ASC Working Paper 30 / 1998 2 Contents Introduction 5 Land use policies: historical overview 6 The magnitude of urban farming in Nairobi since the 1980s 8 Who are the urban farmers in Nairobi? 11 Farming practices 15 The importance of urban farming for the people involved 19 Constraints faced by the urban farmers 22 Prospects for urban farming in Nairobi 27 Conclusion 32 References 35 Appendices 37 3 4 Farming in the City of Nairobi Dick Foeken and Alice Mboganie Mwangi* INTRODUCTION As any visitor to Kenya's capital can see, farming activities are everywhere, not only in the outskirts but also in the heart of the city. Along roadsides, in the middle of roundabouts, along railway lines, in parks, along rivers, under powerlines, in short in all kinds of open, public spaces, crops are cultivated and animals like cattle, goats and sheep are roaming around. What most visitors do not see is that there is even more farming, notably in the backyards of the houses in the residential areas. People of all socio-economic classes grow food whenever and wherever possible. Farming in Nairobi — as well as in cities all over the world — is not a new or recent pheno- menon. Urban agriculture is as old as the towns and cities themselves. However, particularly in the less-developed countries, urban farming has grown enormously since the 1980s, especially among the urban poor. This has most of all to do with growing unemployment rates in combination with increased food prices.