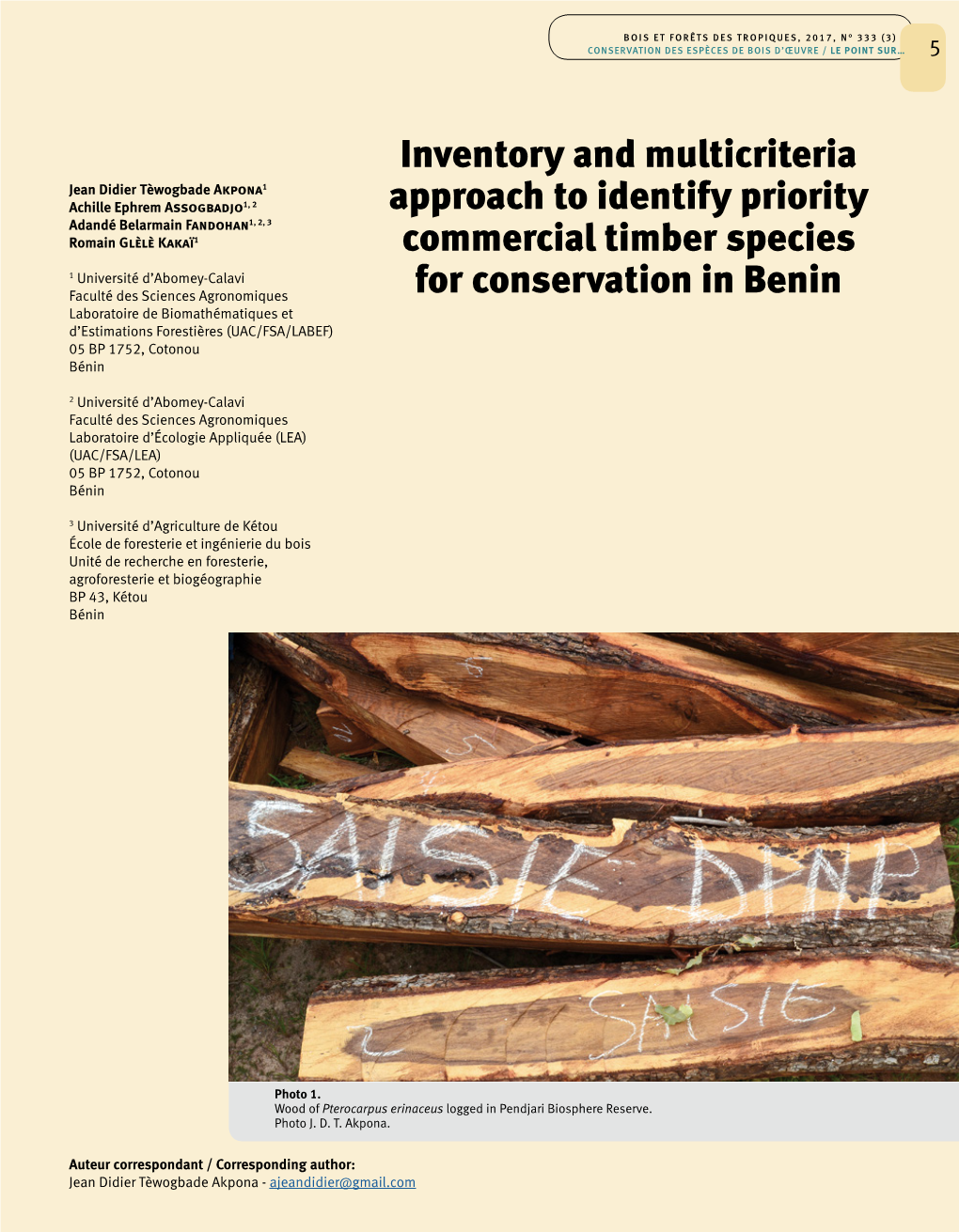

Inventory and Multicriteria Approach to Identify

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBES-Vol-11-No-5-P-3

J. Bio. Env. Sci. 2017 Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences (JBES) ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print) 2222-3045 (Online) Vol. 11, No. 5, p. 37-45, 2017 http://www.innspub.net RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Assessment of habitat/species management area for Kobs in Kainji Lake National Park, Nigeria Oyeleke*, Olaide Omowumi, Ayesuwa, Abimbola Department of Ecotourism and Wildlife Management, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria Article published on November 08, 2017 Key words: Park management, Habitat management, Protected area, Kob courts Abstract Habitat management of spectacular species in protected areas requires some level of active intervention. Kainji Lake National Park, Nigeria designated certain areas for the management of Kobs (Kobus kob) known as Kob courts. The study, carried out in Borgu sector of the Park was aimed at assessing the areas, determine measures towards maintenance and the level of intervention. Data collection included direct and indirect methods of animal survey, plant enumeration and interview. 25m x 25m plots were demarcated in the Kob courts within which plant identification was carried out. Results revealed there are twenty-six (26) designated Kob courts on Gilbert Child, Yankari and Shehu Shagari tracks along the Oli river stretch in the Park Terminalia macroptera was dominant tree species in the Kob courts, followed by Gardenia aqualla, Vitellaria paradoxa, Acacia spp. while Daniella oliveri, Burkea africana and Grewia mollis recorded least occurrence. Active management practices are anti-poaching patrols, creation of waterholes and annual burning to encourage new flush and increase visibility by the tourists. Management interventions were not species-specific but common to all the animals. -

Implication on Genetic Multiplicity and Diversity of African Mahogany in Tropical Rainforest

Available online: www.notulaebiologicae.ro Print ISSN 2067-3205; Electronic 2067-3264 AcademicPres Not Sci Biol, 2019, 11(1):21-25. DOI: 10.15835/nsb11110373 Notulae Scientia Biologicae Short Review Phytotherapy and Polycyclic Logging: Implication on Genetic Multiplicity and Diversity of African Mahogany in Tropical Rainforest Amadu LAWAL 1*, Victor A.J. ADEKUNLE 1, Oghenekome U. ONOKPISE 2 1Federal University of Technology Akure, School of Agriculture and Agricultural Technology, Department of Forestry and Wood Technology, Ondo State, Nigeria; [email protected] (*corresponding author); [email protected] 2Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), College of Agriculture and Food Sciences (CAFS), Forestry and Natural Resources Conservation, Tallahassee Florida, United States; [email protected] Abstract There are over 8,000 globally threatened tree species. For each species, there is a different story behind why they are threatened and what values we stand to lose if we do not find the means to save them. Mahogany, a member of Meliaceae, is a small genus with six species. Its straight, fine and even grain, consistency in density and hardness makes it a high valued wood for construction purposes. The bitter bark is widely used in traditional medicine in Africa. The high demand for bark has also led to the total stripping of some trees, complete felling of larger trees to get the bark from the entire length of the tree and bark removal from juvenile trees. These species are now threatened with extinction due to selective and polycyclic logging, and also excessive bark removal. The natural regeneration of mahogany is poor, and mahogany shoot borer Hypsipyla robusta (Moore) attacks prevent the success of plantations within the native area in West Africa. -

Species Accounts

Species accounts The list of species that follows is a synthesis of all the botanical knowledge currently available on the Nyika Plateau flora. It does not claim to be the final word in taxonomic opinion for every plant group, but will provide a sound basis for future work by botanists, phytogeographers, and reserve managers. It should also serve as a comprehensive plant guide for interested visitors to the two Nyika National Parks. By far the largest body of information was obtained from the following nine publications: • Flora zambesiaca (current ed. G. Pope, 1960 to present) • Flora of Tropical East Africa (current ed. H. Beentje, 1952 to present) • Plants collected by the Vernay Nyasaland Expedition of 1946 (Brenan & collaborators 1953, 1954) • Wye College 1972 Malawi Project Final Report (Brummitt 1973) • Resource inventory and management plan for the Nyika National Park (Mill 1979) • The forest vegetation of the Nyika Plateau: ecological and phenological studies (Dowsett-Lemaire 1985) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 1997 report (Patel 1999) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 2001 report (Patel & Overton 2002) • Evergreen forest flora of Malawi (White, Dowsett-Lemaire & Chapman 2001) We also consulted numerous papers dealing with specific families or genera and, finally, included the collections made during the SABONET Nyika Expedition. In addition, botanists from K and PRE provided valuable input in particular plant groups. Much of the descriptive material is taken directly from one or more of the works listed above, including information regarding habitat and distribution. A single illustration accompanies each genus; two illustrations are sometimes included in large genera with a wide morphological variance (for example, Lobelia). -

Khaya Grandifoliola and K. Senegalensis Family: Meliaceae African Mahogany Benin Mahogany Senegal Mahogany

Khaya grandifoliola and K. senegalensis Family: Meliaceae African Mahogany Benin Mahogany Senegal Mahogany Other Common Names: Diala-iri (Ivory Coast, Ghana), Akuk, Ogwango (Nigeria), Eri Kiree (Uganda), Bandoro (Sudan). Often marketed together with K. ivorensis and K. anthotheca. Distribution: West tropical Africa from the Guinea Coast to Cameroon and extending eastward through the Congo basin to Uganda and parts of Sudan. Often found in the fringe between the rain forest and the savanna. The Tree: Reaches a height of 100 to 130 ft, boles sometimes twisted or crooked with low branching; trunk diameters above buttresses 3 to 5 ft. The Wood: General Characteristics: Heartwood fairly uniform pink- to red brown darkening to a rich mahogany brown; sapwood is lighter in color, not always sharply defined. Texture moderately coarse; grain straight, interlocked, or irregular; without taste or scent. Weight: Basic specific gravity (ovendry weight/green volume) about 0.55 to 0.65; air dry density 42 to 50 pcf. Mechanical Properties: (2-cm standard) Moisture content Bending strength Modulus of elasticity Maximum crushing strength (%) (Psi) (1,000 psi) (Psi) Green (40) 10,000 1,320 5,200 12% 14,100 1,540 8,000 12% (44) 13,800 NA 8,200 Janka side hardness 1,170 lb for green and 1,350 lb for dry material. Amsler toughness 190 in.-lb at 12% moisture content (2-cm specimen). Drying and Shrinkage: Dries rather slowly but fairly well with little checking or warp. Kiln schedule T2-D4 is suggested for 4/4 stock and T2-D3 for 8/4. Shrinkage green to 12% moisture content: radial 2.5%; tangential 4.5%. -

Biosystematics, Morphological Variability and Status of the Genus Khaya in South West Nigeria

Applied Tropical Agriculture Volume 21, No.1, 159-166, 2016. © A publication of the School of Agriculture and Agricultural Technology, The Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. Biosystematics, Morphological Variability and Status of the Genus Khaya in South West Nigeria Lawal, A.1*, Adekunle, V.A.J.1 and Onokpise, O.U.2 1Department of Forestry and Wood Technology, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria. 2Forestry and Natural Resources Conservation, Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), Tallahassee, Florida, USA. * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT There are about 900 different kinds of trees in Nigeria; some are easily recognized but many can only be named with certainty, when flower or fruits are available. Some tree species remain several years without flowering. For this reason, the use of vegetative characteristics to distinguish between tree families, genera or species is the norm. However, different individuals of the same species may present a variation in their morphology either naturally or in connection with local adaptations. Khaya species are among the important timber tree species in Nigeria as well as in some west and central African countries. There has been a serious and growing concern regarding the status and use of these forest resources in Nigeria. However, some researchers have pointed out that Khaya is one of the genus that is threatened by extinction because of the high level of exploitation with little or no regeneration. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the current status of Khaya species for conservation and to conduct research that will provide up-to-date information on the morphological characteristics of species in this genus to enhance their taxonomic identification. -

Mallocybe Africana (Inocybaceae, Fungi), the First Species of Mallocybe Described from Africa

Phytotaxa 478 (1): 049–060 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.478.1.3 Mallocybe africana (Inocybaceae, Fungi), the first species of Mallocybe described from Africa HYPPOLITE L. AIGNON1,5*, AROOJ NASEER2,6, BRANDON P. MATHENY3,7, NOUROU S. YOROU1,8 & MARTIN RYBERG4,9 1 Research Unit Tropical Mycology and Plant-Soil Fungi Interactions, Faculty of Agronomy, University of Parakou, 03 BP 125, Parakou, Benin. 2 Department of Botany, University of the Punjab, Quaid-e-Azam Campus-54590, Lahore, Pakistan. 3 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA. 4 Systematic Biology program, Department of Organismal Biology, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 17D, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden. 5 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3014-9194 6 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4458-9043 7 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3857-2189 8 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6997-811X 9 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6795-4349 *Corresponding author: �[email protected] Abstract The family Inocybaceae has been poorly studied in Africa. Here we describe the first species of the genus Mallocybe from West African and Zambian woodlands dominated by ectomycorrhizal trees of Fabaceae and Phyllanthaceae. The new species M. africana is characterized by orange-brown fruitbodies, a fibrillose pileus, a stipe tapered towards the base and large ellipsoid basidiospores. It resembles many north and south temperate species of Mallocybe but is most closely related to the southeast Asian tropical species, M. -

Nupe Plants and Trees Their Names And

NUPE PLANTS AND TREES THEIR NAMES AND USES [DRAFT -PREPARED FOR COMMENT ONLY] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: January 10, 2008 Roger Blench Nupe plant names – Nupe-Latin Circulation version TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................ 1 TABLES........................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. THE NUPE PEOPLE AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................... 2 2.1 Nupe society ........................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 The environment of Nupeland ............................................................................................................. 3 3. THE NUPE LANGUAGE .......................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 General .................................................................................................................................................. -

Dagomba Plant Names

DAGOMBA PLANT NAMES [PRELIMINARY CIRCULATION DRAFT FOR COMMENT] 1. DAGBANI-LATIN 2. LATIN-DAGBANI [NOT READY] 3. LATIN-ENGLISH COMMON NAMES [NOT READY] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Cambridge, 19 May, 2006 Roger Blench Dagomba plant names and uses Circulation version TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS............................................................................................................................I 1. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................. II 2. TRANSCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... II Vowels ....................................................................................................................................................iii Consonants.............................................................................................................................................. iv Tones....................................................................................................................................................... iv Plurals and other forms ............................................................................................................................ v 3. BOTANICAL SOURCES.................................................................................................................... -

Functions of Farmers' Preferred Tree Species and Their Potential

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/344408; this version posted June 11, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Functions of farmers’ preferred tree species and their potential carbon stocks in 2 southern Burkina Faso: implications for biocarbon initiatives 3 Kangbéni Dimobe*1,2, Jérôme E. Tondoh1,3, John C. Weber4, Jules Bayala5, Karen 4 Greenough6, Antoine Kalinganire5 5 1West African Science Service Centre for Climate Change and Adapted Land Use 6 (WASCAL) Competence Center, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 7 2University Ouaga I Pr Joseph Ki-Zerbo, UFR/SVT, Laboratory of Plant Biology and 8 Ecology, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 9 3UFR des Sciences de la Nature, Université Nangui Abrogoua, Côte d’Ivoire 10 4World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Lima, Peru 11 5World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), West and Central Africa, Sahel Node, Bamako, 12 Mali 13 6L’Université du Faso (UFA), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso 14 Corresponding author 15 E-mail: [email protected] (KD) 16 Author Contributions 17 Conceptualization: Jérôme E. Tondoh, Kangbéni Dimobe, 18 Data curation: Kangbéni Dimobe, Jérôme E. Tondoh 19 Formal analysis: Kangbéni Dimobe. 20 Funding acquisition: Antoine Kalinganire, Jules Bayala, Jérôme E. Tondoh, John C. 21 Weber, 22 Methodology: Jérôme E. Tondoh, John C. Weber, Kangbéni Dimobe, 23 Software: Kangbéni Dimobe 24 Writing - original draft: Jérôme E. Tondoh, Kangbéni Dimobe, 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/344408; this version posted June 11, 2018. -

Effect of Aqueous Extract of Khaya Grandifoliola C. DC. Stem Bark on Some Disaccharidases Activity in Iron-Deficient Weanling Rats

Asian Journal of Research in Biochemistry 7(3): 1-7, 2020; Article no.AJRB.60874 ISSN: 2582-0516 Effect of Aqueous Extract of Khaya grandifoliola C. DC. Stem Bark on some Disaccharidases Activity in Iron-Deficient Weanling Rats Emmauel Gboyega Ajiboye1* and Temidayo Adenike Oladiji1 1Department of Biochemistry, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Author EGA designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors EGA and TAO managed the analyses of the study. Author EGA managed the literature searches. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJRB/2020/v7i330138 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Mohamed Fawzy Ramadan Hassanien, Zagazig University, Egypt. Reviewers: (1) Eugenia Henriquez-D’Aquino, University of Chile, Chile. (2) B. Kumudhaveni, Madras Medical College, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/60874 Received 27 June 2020 Original Research Article Accepted 03 September 2020 Published 08 September 2020 ABSTRACT This study was aimed at investigating the effect of the aqueous extracts of Khaya grandifoliola stem bark on some disaccharidases (lactase and sucrase) in diet-induced anemia in weanling rats. Weanling rats of 21 days old were maintained on iron-deficient diets for four weeks to induce anemia before treatment. A total of 35 weanling rats were used, grouped into five rats per group of iron-deficient diet/distilled water, iron-sufficient diet/distilled water, change of iron-deficient diet after four weeks to iron-sufficient diet, iron-deficient diet/ Standard drug, iron-deficient diet/25 mg/kg body weight of aqueous plant extract, iron-deficient diet/50 mg/kg body weight of aqueous plant extract, and iron-deficient diet/100 mg/kg body weight of aqueous plant extract. -

Identification of Plants Visited by the Honeybee, Apis Mellifera L. in the Sudan Savanna Zone of Northeastern Nigeria

Vol. 7(7), pp. 273-284, July 2013 DOI: 10.5897/AJPS2013.1035 ISSN 1996-0824 ©2013 Academic Journals African Journal of Plant Science http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPS Full Length Research Paper Identification of plants visited by the honeybee, Apis mellifera L. in the Sudan Savanna zone of northeastern Nigeria Usman H. Dukku 1Biological Sciences Programme, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, P.M.B. 0248, Bauchi 740004, Nigeria. 2LLH Bieneninstitut Kirchhain, Erlenstrasse 9, 35274 Kirchhain, Germany. Accepted 10 June, 2013 A total of 61 species of savanna plants visited by the honeybee, Apis mellifera L. were identified through direct observation of foraging bees. The time of flowering of the plants was also recorded. The largest number of species (26.2%) was recorded for the family Fabaceae. Combretaceae ranked second with 9.8% of the species, while Arecaceae, Lamiaceae, Poaceae Rhamnaceae and Rubiaceae ranked third each with 4.9% of the species. Each of the remaining families had 2 or 1 species. Many of the species are being reported as bee plants for the first time. An overlap of the periods of flowering of the plants, which made forage available to the bees throughout the year, was observed. Key words: Savanna, bee plants, honeybee plants, bee forage, Apis mellifera, Bauchi, Nigeria. INTRODUCTION The honeybee, Apis mellifera, depends wholly on plants 2012); palynological analysis of honey (Adekanmbi and for food. Honeybee workers make thousands of visits to Ogundipe, 2009); analysis of pollen loads removed from flowers in order to collect nectar and pollen. While doing returning foragers (Köppler et al., 2007); and analysis of this they pollinate these flowers, thereby helping to pollen stores in nests or hives (Ramanujam and Kalpana, increase fruit and seed-setting both in wild and cultivated 1992). -

Effects of Aqueous Bark Extracts of Khaya Grandifoliola and Enantia

Iranian Journal of Toxicology Volume 11, No 5, September-October2017 Original Article Effects of Aqueous Bark Extracts of Khaya grandifoliola and Enantia chlorantha on Some Biochemical Parameters in Swiss Mice Ismaila Olanrewaju Nurain*1, Clement Olatunbosun Bewaji 2 Received: 31.04.2017 Accepted: 13.06.2017 ABSTRACT Background: In this study, the potential side effects of Khaya grandifolola (KG) and Enatia chlorantha (EC) were investigated on liver function and hematological parameters of Swiss albino mice infected with malaria. Method: This study was carried out in part in the Department of Biochemistry, Kwara State University, Malete, and in part in the Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria, 2016. Aqueous extracts of both KG and EC were screened for the presence of some phytochemicals using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Five groups of eight animals each were used. Group A was administered with only distilled water. Group B was administered with 50 mg/kg body weight of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Groups C, D, and E were treated with 400 mg/kg body weight of KG, EC and KG-EC combination, respectively. After 28 d, the animals were sacrificed for biochemical analysis. Results: The levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin activities were not significantly different (P˂0.05) in all the extract treated animal groups as compared to ACT. However, there was increase in the concentrations of ATL and total bilirubin when compared with that of controls. There was no significant difference (P˂0.05) among Hb, RBC, PCV, WBC, lymphocytes, and platelets compared with ACT.