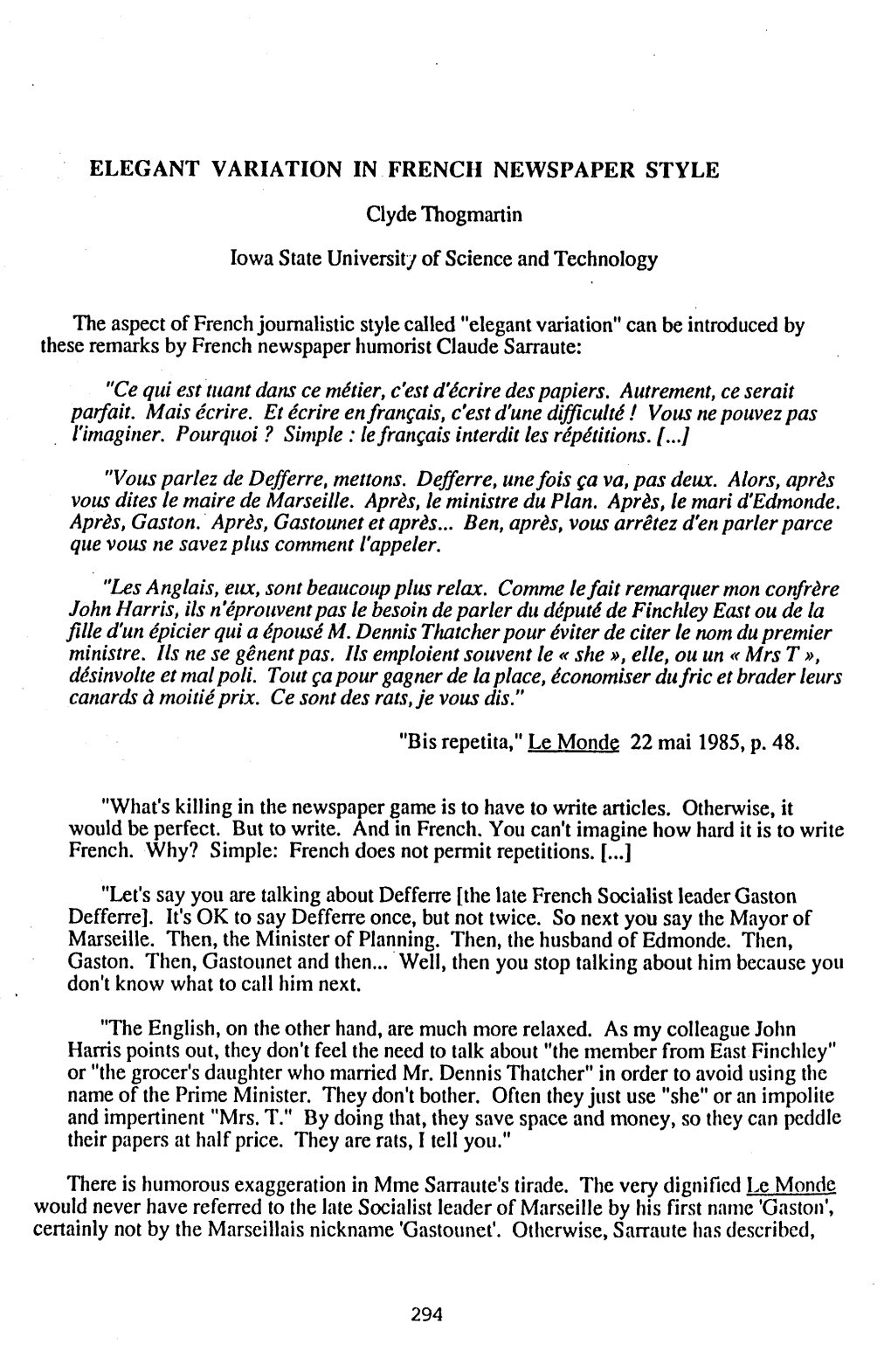

Elegant Variation in French Newspaper Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Social Dialogue the History of a Social Innovation (1985-2003) — Jean Lapeyre Foreword by Jacques Delors Afterword by Luca Visentini

European Trade Union Institute Bd du Roi Albert II, 5 1210 Brussels Belgium +32 (0)2 224 04 70 [email protected] www.etui.org “Compared to other works on the European Social Dialogue, this book stands out because it is an insider’s story, told by someone who was for many years the linchpin, on the trade unions’ side, of this major accomplishment of social Europe.” The European social dialogue — Emilio Gabaglio, ETUC General Secretary (1991-2003) “The author, an ardent supporter of the European Social Dialogue, has put his heart and soul into this The history of a social meticulous work, which is enriched by his commitment as a trade unionist, his capacity for indignation, and his very French spirit. His book will become an essential reference work.” — Wilfried Beirnaert, innovation (1985-2003) Managing Director and Director General at the Federation of Belgian Enterprises (FEB) (1981-1998) — “This exhaustive appraisal, written by a central actor in the process, reminds us that constructing social Europe means constructing Europe itself and aiming for the creation of a European society; Jean Lapeyre something to reflect upon today in the face of extreme tendencies which are threatening the edifice.” — Claude Didry, Sociologist and Director of Research at the National Centre of Scientific Research (CNRS) Foreword by Jacques Delors (Maurice Halbwachs Centre, École Normale Supérieure) Afterword by Luca Visentini This book provides a history of the construction of the European Social Dialogue between 1985 and 2003, based on documents and interviews with trade union figures, employers and dialogue social European The The history of a social innovation (1985-2003) Jean Lapeyre European officials, as well as on the author’s own personal account as a central actor in this story. -

The Sarkozy Effect France’S New Presidential Dynamic J.G

Politics & Diplomacy The Sarkozy Effect France’s New Presidential Dynamic J.G. Shields Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidential campaign was predicated on the J.G. Shields is an associate professor of need for change in France, for a break—“une rupture”—with the French Studies at the past. His election as president of the French Republic on 6 University of Warwick in England. He is the first May 2007 ushered in the promise of a new era. Sarkozy’s pres- holder of the American idency follows those of the Socialist François Mitterrand Political Science Associ- ation's Stanley Hoff- (1981-95) and the neo-Gaullist Jacques Chirac (1995-2007), mann Award (2007) for who together occupied France’s highest political office for his writing on French more than a quarter-century. Whereas Mitterrand and Chirac politics. bowed out in their seventies, Sarkozy comes to office aged only fifty-two. For the first time, the French Fifth Republic has a president born after the Second World War, as well as a presi- dent of direct immigrant descent.1 Sarkozy’s emphatic victory, with 53 percent of the run-off vote against the Socialist Ségolène Royal, gave him a clear mandate for reform. The near-record turnout of 84 percent for both rounds of the election reflected the public demand for change. The legislative elections of June 2007, which assured a strong majority in the National Assembly for Sarkozy’s centre-right Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP), cleared the way for implementing his agenda over the next five years.2 This article examines the political context within which Sarkozy was elected to power, the main proposals of his presidential program, the challenges before him, and his prospects for bringing real change to a France that is all too evidently in need of reform. -

RÊVEUR RÉALISTE RÉFORMISTE RADICAL FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE MICHEL ROCARD Préface D’Alain Bergounioux Rêveur Réaliste, Réformiste Radical

L A C I D A R E T S I M R O F É R , E T S I L A É R R RÊVEUR RÉALISTE U E V RÉFORMISTE RADICAL Ê R FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE MICHEL ROCARD Préface d’Alain Bergounioux RÊVEUR RÉALISTE RÉFORMISTE RADICAL FRANÇOIS HOLLANDE MICHEL ROCARD Préface d’Alain Bergounioux Rêveur réaliste, réformiste radical RÉFORMISME RADICAL Alain Bergounioux Celles et ceux qui ont assisté à la remise de la Grand-Croix de la Légion d’honneur à Michel Rocard par le président de la République n’ont pu qu’être frappés par l’intensité du moment. Il est, certes, toujours émouvant d’entendre revivre une soixantaine d’années faites d’engagements, de réflexions, d’actions, qui ont suscité une adhésion dans plusieurs générations. Mais François Hollande, comme Michel Rocard, se sont attachés surtout à mettre en évidence ce qu’ont été et ce que sont les fondements d’une action qui a marqué la gauche et le pays. La confrontation des deux discours, malgré des intentions et des styles différents, montre un accord sur un constat. François Hollande l’a formulé pour Michel Rocard – qui ne pouvait pas le dire lui-même, même si toute son intervention le manifeste. « Si je pouvais résumer, concluait le président, vous êtes un rêveur réaliste, un réformiste radical ». « Un rêveur réaliste » ou un « réformiste radical » correspondent bien à la personnalité de Michel Rocard, pour celles et ceux qui le connaissent, et au sens d’une pensée et d’une action qui ne se laissent pas caractériser simplement. Selon les contextes et les responsabilités exercées, les accents peuvent ne pas être les mêmes, le « réalisme » l’emportant sur le « rêveur » ou l’inverse. -

Lionel Jospjn

FACT SHEET N° 5: CANDIDATES' BIOGRAPHIES LIONEL JOSPJN • Lionel Jospin was born on 12 July 1937 in Meudon (Houts de Seine). The second child in a family of four, he spent his whole childhood in the Paris region, apart from a period during the occupation, and frequent holidays in the department of Tam-et-Garonne, from where his mother originated. First a teacher of French and then director of a special Ministry of Education school for adolescents with problems, his father was an activist in the SFIO (Section franr;aise de l'intemationale ouvrierej. He was a candidate in the parliamentary elections in l'lndre in the Popular Front period and, after the war, the Federal Secretary of the SFIO in Seine-et-Marne where the family lived. Lionel Jospin's mother. after being a midwife, became a nurse and school social worker. EDUCATION After his secondary education in Sevres, Paris, Meaux and then back in Paris, lionel Jospin did a year of Lettres superieures before entering the Paris lnstitut d'efudes politiquesin 1956. Awarded a scholarship, he lived at that time at the Antony cite universitaire (student hall of residence). It was during these years that he began to be actively involved in politics. Throughout this period, Lionel Jospin spent his summers working as an assistant in children's summer camps (colonies de vacances'J. He worked particularly with adolescents with problems. A good basketball player. he also devoted a considerable part of his time to playing this sport at competitive (university and other) level. After obtaining a post as a supervisor at ENSEP, Lionel Jospin left the Antony Cite universifaire and prepared the competitive entrance examination for ENA. -

Updating the Debate on Turkey in France, Note Franco-Turque N° 4

NNoottee ffrraannccoo--ttuurrqquuee nn°° 44 ______________________________________________________________________ Updating the Debate on Turkey in France, on the 2009 European Elections’ Time ______________________________________________________________________ Alain Chenal January 2011 . Programme Turquie contemporaine The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of the European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. Contemporary Turkey Program is supporter by : ISBN : 978-2-86592-814-9 © Ifri – 2011 – All rights reserved Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE 1000 – Brussels – BELGIUM Tel : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tel : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax : +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email : [email protected] Email : [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Notes franco-turques The IFRI program on contemporary Turkey seeks to encourage a regular interest in Franco-Turkish issues of common interest. From this perspective, and in connection with the Turkish Season in France, the IFRI has published a series of specific articles, entitled “Notes franco-turques” (Franco-Turkish Briefings). -

Intérieur ; Cabinet De Gaston Defferre, Ministre De L'intérieur Puis De Pierre

Intérieur ; Cabinet de Pierre Joxe, ministre de l'Intérieur. Dossiers de François Roussely, directeur de cabinet du ministre (1988-1989) Répertoire numérique du versement 19910204 Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1991 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_008128 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2010 par l'entreprise diadeis dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Sommaire Intérieur ; Cabinet de Pierre Joxe, ministre de l'Intérieur. Dossiers de François 4 Roussely, directeur de cabinet du ministre (1988-1989) Instructions du Premier ministre 6 Administration centrale 6 Préparation du budget 1989 6 Conflits sociaux 6 Aménagement du territoire 7 Administration des territoires basque, corse, francilien et néo-calédonien 7 Pays basque 7 Corse 7 Nouvelle-Calédonie 8 Paris - Ile-de-France 9 Dossiers en lien avec la Direction des libertés publiques et des affaires juridiques 9 (DLPAJ) Dossiers en lien avec la direction générale de la police nationale 9 Dossier général 9 Affaires traitées par la DCPJ 10 Dossiers en lien avec la direction de la Sécurité civile 10 Dossiers en lien avec l'Inspection générale de l'administration (IGA) 11 Communauté européenne 11 Fonctions publiques 11 Jeux Olympiques d'hiver à Alberville 11 Relations avec le Parti socialiste 12 Réunions des directeurs généraux et des directeurs du ministère de l'Intérieur 12 3 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 19910204/1-19910204/4 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Intérieur ; Cabinet de Pierre Joxe, ministre de l'Intérieur. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

Macroeconomic and Monetary Policy-Making at the European Commission, from the Rome Treaties to the Hague Summit

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Maes, Ivo Working Paper Macroeconomic and monetary policy-making at the European Commission, from the Rome Treaties to the Hague Summit NBB Working Paper, No. 58 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: Maes, Ivo (2004) : Macroeconomic and monetary policy-making at the European Commission, from the Rome Treaties to the Hague Summit, NBB Working Paper, No. 58, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/144272 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu NATIONAL BANK OF BELGIUM WORKING PAPERS - RESEARCH SERIES MACROECONOMIC AND MONETARY POLICY-MAKING AT THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, FROM THE ROME TREATIES TO THE HAGUE SUMMIT _______________________________ Ivo Maes (*) The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bank of Belgium. -

Entretien Avec Jacqueline Lastenouse

Anne Dulphy et Christine Manigand, « Entretien avec Jean-Bernard Raimond », Histoire@Politique. Politique, culture, société, n° 16, janvier-avril 2012, www.histoire-politique.fr Entretien avec Jean-Bernard Raimond Propos recueillis à Paris le 17 octobre 2011 par Anne Dulphy et Christine Manigand Jean-Bernard Raimond est né en 1926. Ancien élève de la rue d’Ulm et de l’ENA, agrégé de lettres classiques, ambassadeur de France, il a été ministre des Affaires étrangères de 1986 à 1988 et membre de l’Assemblée nationale de 1993 à 2002. Il a publié quatre ouvrages, Le Quai d’Orsay à l’épreuve de la cohabitation (Flammarion, 1989), Le choix de Gorbatchev (Odile Jacob, 1992), Jean-Paul II, un Pape au cœur de l’histoire (Le Cherche Midi, 1999 et 2005), et Le regard d’un diplomate sur le monde. Les racines des temps nouveaux 1960-2010 (Le Félin, 2010). Y a-t-il dans votre environnement de jeunesse des éléments qui vous ont conduit à ce parcours d’excellence qui vous a mené de l’ENS à l’ENA et à l’agrégation ? Je suis né à Paris, mais avec des origines provinciales très nettes. Par ma mère je suis 50 % Corrézien et par mon père je suis 25 % Bordelais et 25 % de Cholet. Pour me définir, je suis fondamentalement Parisien. J’ai toujours été élève de l’enseignement public d’un bout à l’autre et ma grande révélation intellectuelle a été mon entrée en sixième A au lycée. Je suis né en 1926, je suis entré en sixième en 1937, au lycée Charlemagne et, là, j’ai été transporté d'enthousiasme ! C’était donc l’enseignement des années 1930, dans un lycée parisien avec des professeurs remarquables. -

The Algerian War, European Integration and the Decolonization of French Socialism

Brian Shaev, University Lecturer, Institute for History, Leiden University The Algerian War, European Integration, and the Decolonization of French Socialism Published in: French Historical Studies 41, 1 (February 2018): 63-94 (Copyright French Historical Studies) Available at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/french-historical-studies/article/41/1/63/133066/The-Algerian- War-European-Integration-and-the https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-4254619 Note: This post-print is slightly different from the published version. Abstract: This article takes up Todd Shepard’s call to “write together the history of the Algerian War and European integration” by examining the French Socialist Party. Socialist internationalism, built around an analysis of European history, abhorred nationalism and exalted supranational organization. Its principles were durable and firm. Socialist visions for French colonies, on the other hand, were fluid. The asymmetry of the party’s European and colonial visions encouraged socialist leaders to apply their European doctrine to France’s colonies during the Algerian War. The war split socialists who favored the European communities into multiple parties, in which they cooperated with allies who did not support European integration. French socialist internationalism became a casualty of the Algerian War. In the decolonization of the French Socialist Party, support for European integration declined and internationalism largely vanished as a guiding principle of French socialism. Cet article adresse l’appel de Todd Shepard à «écrire à la fois l’histoire de la guerre d’Algérie et l’histoire de l'intégration européenne» en examinant le Parti socialiste. L’internationalisme socialiste, basé sur une analyse de l’histoire européenne, dénonça le nationalisme et exalta le supranationalisme. -

The Coming Chirac-Sarkozy Prize Fight

The Coming Chirac- Sarkozy B Y P HILIPPE R IÈS Prize Fight t the European Council last March, European journal- ists looked stunned as French President Jacques Chirac went into a lengthy rant against “liberal globalization” at his final press conference. One joked afterward that he expected Chirac to stand up, raise a tight fist, and But will France when start singing the old “Internationale” workers anthem. At the summit, Chirac, nominally a conservative, reportedly told his fellow European heads of state and it’s over be left with government that “liberalism (i.e., pro free-market and deregulation in the AEuropean meaning of the word) was the communism of our days,” a kind of fundamentalism that would deliver equally catastrophic results. any hope for the prize Actually, the tirade was not so surprising coming from a man who strongly supports a Tobin tax of a sort on international financial transactions to fund of genuine reform? development aid and regards Brazilian leftist President Lula da Silva as a “com- rade.” And if you get confused, you are not alone. So have been the French peo- ple and Chirac’s own political allies. In a political career spread over more than three decades, Chirac has earned a well-deserved reputation for ideological inconsistency. This one-time advocate of French-styled “Labour” policies (“travaillisme à la française”) has been an ineffective prime minister under President Valery Giscard d’Estaing. Back to the same position under socialist President François Mitterrand, in an arrange- THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY ment called “cohabitation” (when the president and the prime minister come 888 16th Street, N.W., Suite 740 Washington, D.C. -

Insular Autonomy: a Framework for Conflict Settlement? a Comparative Study of Corsica and the Åland Islands

INSULAR AUTONOMY: A FRAMEWORK FOR CONFLICT SETTLEMENT? A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CORSICA AND THE ÅLAND ISLANDS Farimah DAFTARY ECMI Working Paper # 9 October 2000 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor Building) D-24939 Flensburg . Germany % +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper # 9 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Marc Weller Issue Editors: Farimah Daftary and William McKinney © European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) 2000. ISSN 1435-9812 i The European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) is a non-partisan institution founded in 1996 by the Governments of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the German State of Schleswig-Holstein. ECMI was established in Flensburg, at the heart of the Danish-German border region, in order to draw from the encouraging example of peaceful coexistence between minorities and majorities achieved here. ECMI’s aim is to promote interdisciplinary research on issues related to minorities and majorities in a European perspective and to contribute to the improvement of inter-ethnic relations in those parts of Western and Eastern Europe where ethno- political tension and conflict prevail. ECMI Working Papers are written either by the staff of ECMI or by outside authors commissioned by the Centre. As ECMI does not propagate opinions of its own, the views expressed in any of its publications are the sole responsibility of the author concerned. ECMI Working Paper # 9 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) © ECMI 2000 CONTENTS I.